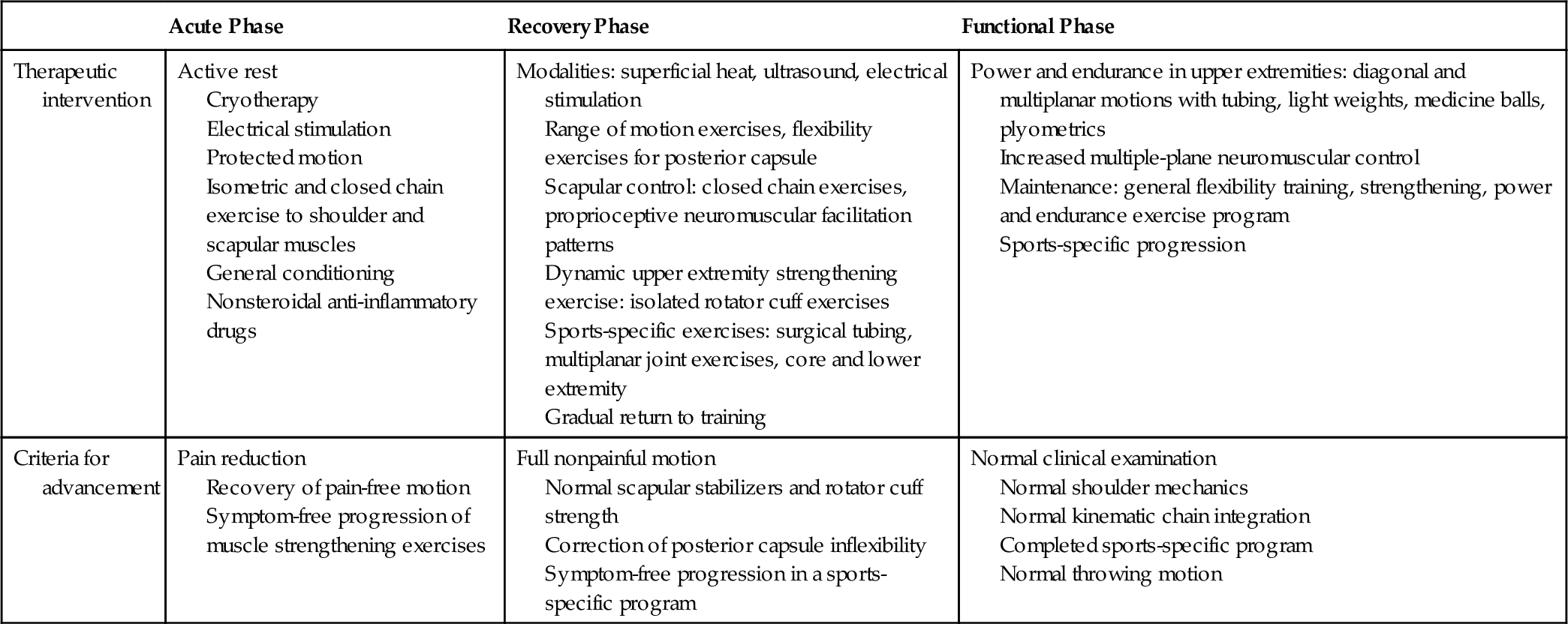

CHAPTER 14

Glenohumeral Instability

Definitions

Shoulder instability represents a spectrum of disorders ranging from shoulder subluxation, in which the humeral head partially slips out of the glenoid fossa, to shoulder dislocation, which is a complete displacement of the humeral head out of the glenoid. It is classified as anterior, posterior, or multidirectional and on the basis of its frequency, etiology, direction, and degree. Instability can result from macrotrauma, such as shoulder dislocation, or repetitive microtrauma associated with overhead activity, and it can occur without trauma in individuals with generalized ligamentous laxity [1–4].

The glenohumeral joint has a high degree of mobility at the expense of stability. Static and dynamic restraints combine to maintain the shoulder in place with overhead activity. Muscle action, particularly of the rotator cuff and scapular stabilizers, is important in maintaining joint congruity in midranges of motion. Static stabilizers, such as the glenohumeral ligaments, the joint capsule, and the glenoid labrum, are important for stability in the extremes of motion [2].

Traumatic damage to the shoulder capsule, the glenohumeral ligaments, and the inferior labrum is a result of acute dislocation. Repeated capsular stretch, rotator cuff, and superior labral injuries are associated with overuse injury resulting in anterior instability in athletes who participate in overhead sports; a loose patulous capsule is the primary pathologic change with multidirectional instability, and patients may present with bilateral symptoms [4–6]. Shoulder instability affects, in particular, young individuals, females, and athletes, but it may also affect sedentary individuals, with an incidence of 1.7% in the general population [1,7,8].

Traumatic instability often occurs when the individual usually falls on an outstretched, externally rotated, and abducted arm with a resulting anterior dislocation. A blow to the posterior aspect of the externally rotated and abducted arm can also result in anterior dislocation. Posterior dislocation usually results from a fall on the forward flexed and adducted arm or by a direct blow in the posterior direction when the arm is above the shoulder [5].

Recurrent shoulder instability after a traumatic dislocation is common, particularly when the initial event happens at a young age. In these individuals, it may occur repeatedly in association with overhead activity, and it may even happen at night, while changing position in bed, in those with severe instability. The patients may initially require visits to the emergency department or reduction of recurrent dislocation by a team physician; but as the condition becomes more chronic, some may be able to reduce their own dislocations [9,10].

Patients with neurologic problems such as stroke, brachial plexus injury, and severe myopathies may develop shoulder girdle muscle weakness, scapular dysfunction, and resultant shoulder instability.

Symptoms

With atraumatic instability or subluxation, it may be difficult to identify an initial precipitating event. Usually, symptoms result from repetitive activity that places great demands on the dynamic and static stabilizers of the glenohumeral joint, leading to increased translation of the humeral head in overhead sports and occupational activities. Pain is the initial symptom, usually associated with impingement of the rotator cuff under the coracoacromial arch. Patients may also report that the shoulder slips out of the joint or that the arm goes “dead,” and they may report weakness associated with overhead activity [1–3,9–11].

Patients with neurologic injury present with pain with motion and shoulder subluxation as well as scapular and shoulder girdle muscle weakness. In the case of a patient with acute shoulder injury, factors to identify include the patient’s age, dexterity or dominant side, sports and position, activity level, mechanism of injury, and any associated symptoms such as neurologic or functional deficits. In cases of acute dislocation, the age at first dislocation is a prognostic indicator in view of a recurrence of 75% to 100%, especially in skeletally immature individuals [11].

Physical Examination

The shoulder is inspected for deformity, atrophy of surrounding muscles, asymmetry, and scapular winging. Individuals are observed from the anterior, lateral, and posterior positions with the shoulder in neutral position on the side of the body as well as with flexion and abduction motion. Palpation of soft tissue and bone is systematically addressed and includes the four joints that compose the shoulder complex (sternoclavicular, acromioclavicular, glenohumeral, and scapulothoracic), rotator cuff, biceps tendon, and subacromial region.

Passive and active range of motion is evaluated. Differences between passive and active motion may be secondary to pain, weakness, or neurologic damage. Repeated throwing may lead to an increase in measured external rotation accompanied by a reduction in internal rotation; tennis players may present with an isolated glenohumeral internal rotation deficit [12]. These changes may be secondary to posterior capsule tightness, humeral torsion, and glenohumeral laxity that may lead to internal impingement [12].

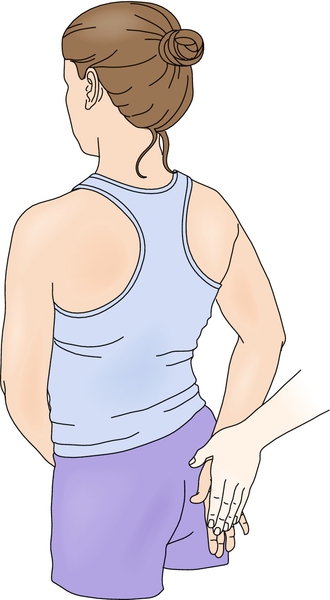

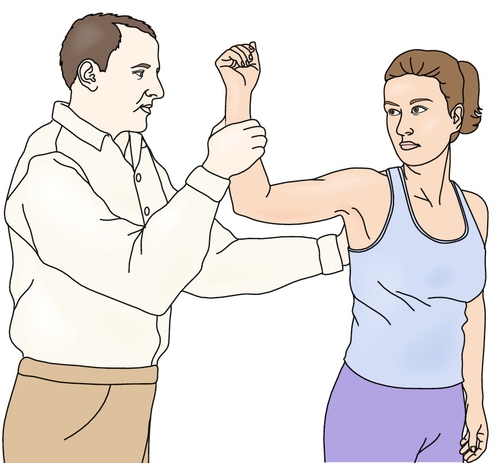

Manual strength testing is performed to identify weakness of specific muscles of the rotator cuff and the scapular stabilizers. The supraspinatus muscle can be tested in the scapular plane with internal rotation or external rotation of the shoulder, and the external rotators are tested with the arm at the side of the body. The subscapularis muscle can be tested by the lift-off test, in which the palm of the hand is lifted away from the lower back (Fig. 14.1). The scapular stabilizers, such as the serratus anterior and the rhomboid muscles, can be tested in isolation or by doing wall pushups. Sensory examination of the shoulder girdle is performed to rule out nerve injuries.

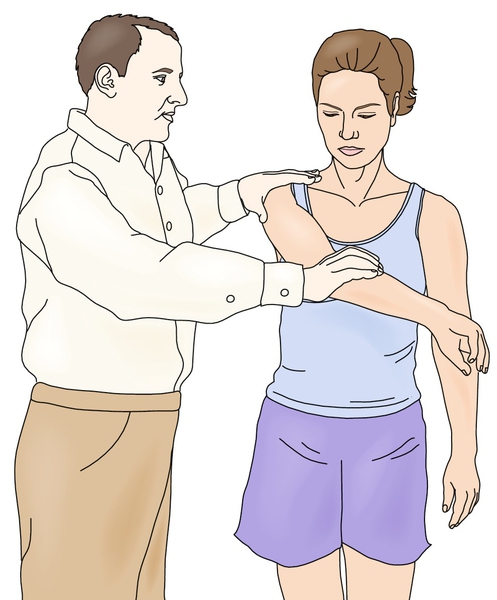

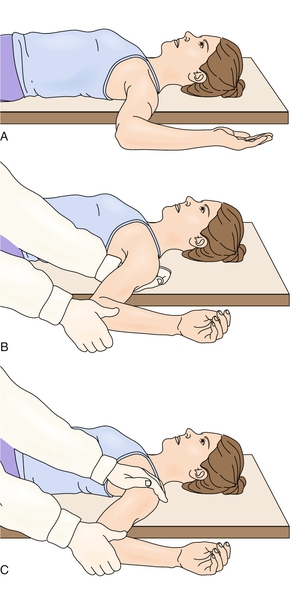

Testing the shoulder in the position of 90 degrees of forward flexion with internal rotation (Hawkins maneuver) or in extreme forward flexion (until 180 degrees) with the forearm pronated (Neer maneuver) can assess for rotator cuff impingement and may reproduce symptoms of pain [10] (Fig. 14.2). Glenohumeral translation testing for ligamentous laxity or symptomatic instability should be documented. Apprehension testing can be performed with the patient sitting, standing, or in the supine position. The shoulder is stressed anteriorly in the position of 90 degrees of abduction and external rotation to reproduce the feeling that the shoulder is coming out of the joint (apprehension test). A relocation maneuver that reduces the symptoms of instability also aids in the diagnosis but appears to be less specific than apprehension testing [11] (Fig. 14.3). The causation of posterior shoulder pain (rather than symptoms of instability) with apprehension testing may be associated with internal impingement of the rotator cuff and posterior superior labrum [13–19] (Fig. 14.4).

Other tests for shoulder laxity include the load and shift maneuver with the arm at the side to document humeral head translation in anterior and posterior directions and the sulcus sign to document inferior humeral head laxity. Labral injuries can be evaluated with a combination of tests including the active compression test described by O’Brien and colleagues in which a downward force is applied to the forward flexed, adducted, and internally rotated shoulder to reproduce pain associated with superior labral tears or acromioclavicular joint disease. In the crank test, pain and clicking are reproduced when the shoulder is abducted to 160 degrees and an axial load is placed on the humerus and the arm is internally and externally rotated. Another test is the biceps loading test, in which the patient is asked to supinate the forearm, abduct the shoulder to 90 degrees, flex the elbow to 90 degrees, and externally rotate the arm until apprehensive and the examiner provides resistance against elbow flexion. Pain would suggest a proximal biceps tendinopathy or a labral tear [13–19].

Functional Limitations

Impairment includes reduced motion, muscle weakness, and pain that interfere with activities of daily living, such as reaching into cupboards and brushing hair. Athletes, particularly those participating in throwing sports, may experience a decrease in the velocity of their pitches, and tennis players may lose control of their serve. Occupational limitations may include inability to reach or to lift weight above the level of the head or pain with rotation of the arm in a production line. Recurrent instability often leads to avoidance of activities that require abduction and external rotation because of reproduction of symptoms.

Diagnostic Studies

The standard radiographs that are obtained to evaluate the patient with shoulder symptoms include anteroposterior views in external and internal rotation, outlet view, axillary lateral view, and Stryker notch view. These allow an assessment of the greater tuberosity and the shape of the acromion and reveal irregularity of the glenoid or posterior humeral head as well as dysplasia, hypoplasia, or bone loss that can contribute to instability [3,20].

Special tests that can also be ordered include arthrography, computed tomographic arthrography, magnetic resonance imaging, and magnetic resonance arthrography. These should be ordered to look for rotator cuff or labral abnormalities in the patient who has not responded to treatment. Magnetic resonance arthrography allows better evaluation of rotator cuff, glenoid labrum, and glenohumeral ligaments [3,21]. Gadolinium contrast enhancement and modification of the position of the arm for the test appear to increase the sensitivity of magnetic resonance imaging in identifying the specific location of capsular or labral pathologic changes associated with recurrent instability and dislocation [3,21]. Musculoskeletal sonography has grown in popularity in the last decade, and its use in shoulder disease has been well documented. Evaluation of shoulder instability is limited to visualization of the posterior labrum and the rotator cuff tendons and evaluation for paralabral cysts that may suggest labral injury [22]. Diagnostic arthroscopy can be used in some cases but is generally not necessary.

Treatment

Initial

Acute management of glenohumeral instability is nonoperative in the majority of cases. This includes relative rest, ice, and analgesic or anti-inflammatory medication. Goals at this stage are pain reduction, protection from further injury, and initiation of an early rehabilitation program.

If the injury was observed (as often occurs in athletes) and no neurologic or vascular damage is evident on clinical examination, reduction may be attempted with traction in forward flexion and slight abduction, followed by gentle internal rotation. If this fails, the patient should be transported away from the playing area; reduction may be attempted by placing the patient prone, sedating the individual, and allowing the injured arm to hang from the bed with a 5- to 10-pound weight attached to the wrist. If fracture or posterior dislocation is suspected, the patient should undergo radiologic evaluation before a reduction is attempted. After the reduction, radiologic studies should be repeated [1,3,23–25].

When acute shoulder dislocations are treated nonoperatively, they are usually managed with 1 to 4 weeks of immobilization in a sling, in which the arm is positioned in internal rotation, followed by an exercise program and gradual return to activity. Several studies have suggested that placement of the arm in a position of external rotation may be more appropriate because of better realignment of anatomic structures and reduction position [23–26]. However, this issue still merits further study because there is a lack of randomized controlled studies demonstrating a significant reduction in recurrent dislocation rates or a difference in return to activity levels in comparing the positions of immobilization after reduction or the duration of the postreduction immobilization period [25].

Rehabilitation

The rehabilitation of glenohumeral instability should begin as soon as the injury occurs. The goals of nonsurgical management are reduction of pain, restoration of full functional motion, correction of muscle strength deficits, achievement of muscle balance, and return to full activity free of symptoms. The rehabilitation program consists of acute, recovery, and functional phases [2–4,17–19] (Table 14.1).

Acute Phase (1 to 2 weeks)

This phase should focus on treatment of tissue injury and clinical signs and symptoms. The goal in this stage is to allow tissue healing while reducing pain and inflammation. Reestablishment of nonpainful active range of motion, prevention of shoulder girdle muscle atrophy, reduction of scapular dysfunction, and maintenance of general fitness are addressed.

Recovery Phase (2 to 6 weeks)

This phase focuses on obtaining normal passive and active glenohumeral range of motion, restoring posterior capsule flexibility, improving scapular and rotator cuff muscle strength, and achieving normal core muscle strength and balance. Flexibility training should include the sleeper stretch; strength training includes exercises for the lower trapezius and serratus anterior muscle. This phase can be started as soon as pain is controlled and the patient can participate in an exercise program without exacerbation of symptoms. Young individuals with symptomatic instability need to progress slowly to the position of shoulder abduction and external rotation. Athletes can progress rapidly through the program and emphasize exercises in functional ranges of motion. Older patients with goals of returning to activities of daily living may require slower progression, particularly if they have significant pain, muscle inhibition, and weakness. Biomechanical and functional deficits including abnormalities in the throwing motion should also be addressed.

Functional Phase (6 weeks to 6 months)

This phase focuses on increasing power and endurance of the upper extremities while improving neuromuscular control because a normal sensorimotor system is key in returning to optimal shoulder function [24]. Rehabilitation at this stage works on the entire kinematic chain to address specific functional deficits.

After the completion of rehabilitation, a continued exercise program with goals of preventing recurrent injury should be instituted for individuals who participate in sports, recreational activities, or work-related tasks in which high demands on the shoulder joint are expected. A training program that combines flexibility and strengthening exercises with neuromuscular as well as proprioceptive training should be ongoing. Patients with multidirectional instability need to work specifically on strengthening of the scapular stabilizers and balancing the force couples between the rotator cuff and the deltoid muscle.

Procedures

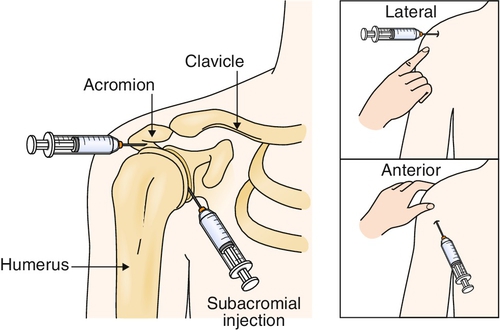

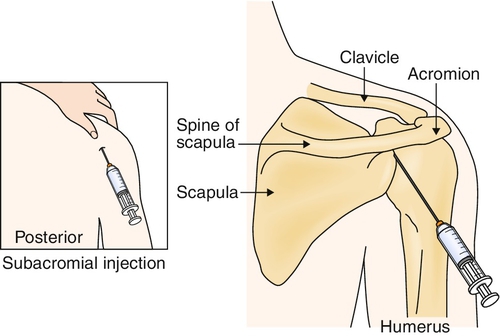

If the individual persists with some symptoms of pain secondary to rotator cuff irritation despite an appropriate rehabilitation program, a subacromial injection could be considered (Figs. 14.5 and 14.6). The patient at that time should be reevaluated for identification of residual functional and biomechanical deficits that need to be addressed in combination with the injection. Under sterile conditions, with use of a 23- to 25-gauge, 11⁄2-inch disposable needle, inject an anesthetic-corticosteroid preparation by an anterior, posterior, or lateral approach with or without sonographic guidance, based on availability and clinician expertise. Typically, 3 to 8 mL is injected (e.g., 4 mL of 1% lidocaine and 2 mL of 40 mg/mL triamcinolone). Alternatively, the lidocaine may be injected first, followed by the corticosteroid. Postinjection care includes local ice for 5 to 10 minutes. The patient is instructed to ice the shoulder for 15 to 20 minutes three or four times daily for the next few days and to avoid aggressive overhead activities for the following week. Other procedures, such as prolotherapy, platelet-rich plasma injections, and ultrasound-guided infiltrations, are becoming more popular, especially in athletes for other musculoskeletal injuries, but the results of use for shoulder instability are still unknown [27].

Surgery

Because of high rates of recurrent instability after conservative treatment in the active athletic population and, in particular, throwers, early surgical intervention is gaining acceptance [28]. Open repair of Bankart lesions has been the standard surgical intervention after traumatic instability, and it is still reported by some authors as the preferred method because of predictable results in regard to recurrence of dislocation and return to activity [28]. Early arthroscopic repair of the inferior labral defect associated with acute shoulder dislocation is becoming widespread because of an apparent reduction in postoperative morbidity that may allow the athlete an early return to function [29–31].

In the individual with recurrent instability, surgical treatment may need to address abnormalities in the shoulder capsule, glenoid labrum, and rotator cuff. Arthroscopic interventions result in comparable outcomes when they are measured against open surgery, but no “gold standard” method has been established [3]. Surgical interventions include capsular procedures, such as the capsular shift, and labral as well as rotator cuff procedures, such as débridement and repair [32,33]. In many instances, these procedures need to be combined for optimal results in the patient, followed by an accelerated rehabilitation program with guidelines similar to those for the patient treated nonoperatively [34]. Rehabilitation protocols are similar for open and arthroscopic techniques. The shoulder is immobilized with an abduction pillow for 4 to 6 weeks, with therapy initiated if stiffness develops. After immobilization, strengthening exercises (similar to nonsurgical protocols) are recommended. If the rehabilitation protocol is successfully completed, the patient is allowed to return to full activity 4 to 6 months after surgery [3,34,35].

Potential Disease Complications

Complications include recurrent instability with overhead activity, pain in the shoulder region, nerve damage, and weakness of the rotator cuff and scapular muscles. These tend to occur more commonly in patients with multidirectional atraumatic instability. Loss of function may include inability to lift overhead and loss of throwing velocity and accuracy. Recurrent episodes of instability in the older individual may also be related to the development of rotator cuff tears [36].

Potential Treatment Complications

Analgesics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have well-known side effects that most commonly affect the gastric, hepatic, cardiovascular, and renal systems. Complications of treatment include loss of motion, failure of surgical repair with recurrent instability, and inability to return to previous level of function. Failure of conservative treatment may be associated with incomplete rehabilitation or poor technique. Recurrent dislocation after surgical treatment can be related to not addressing all the sites of pathologic change at the time of the operation [35].