CASE 14 Extensive Coronary Thrombus

Cardiac catheterization

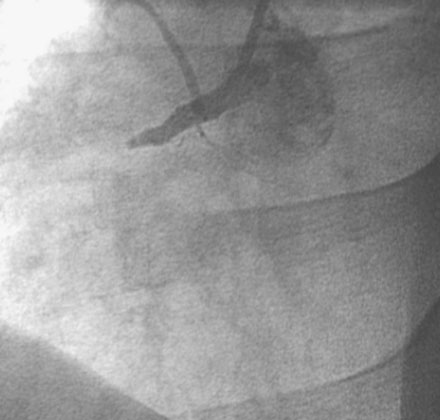

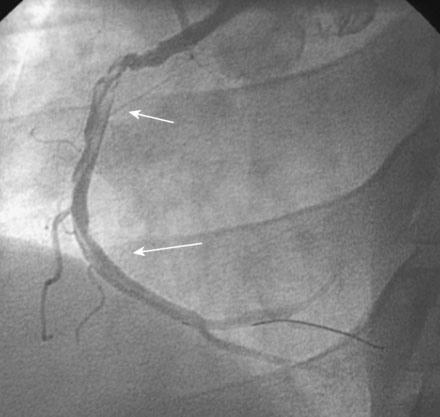

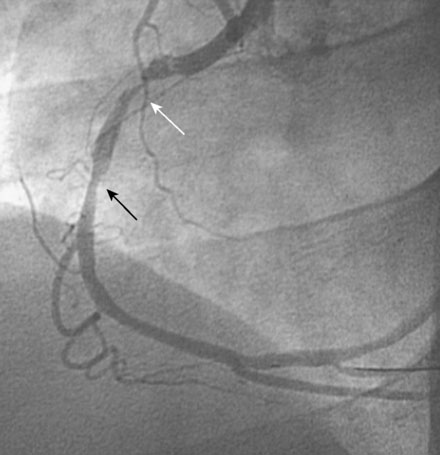

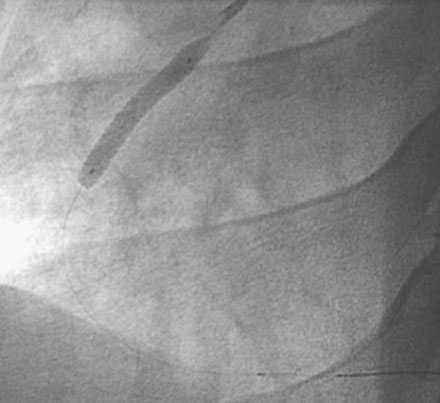

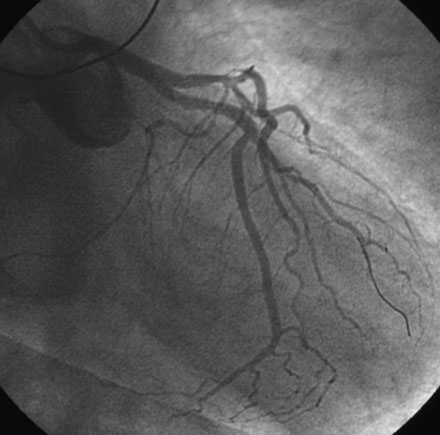

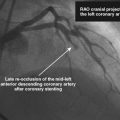

The patient arrived in the cardiac catheterization laboratory approximately 2 hours after receiving thrombolysis. As expected, the right coronary artery was completely occluded (Figure 14-1). There was no significant obstructive disease noted in the left coronary arteries. An additional intravenous bolus of enoxaparin was administered, along with a bolus plus infusion of eptifibatide. The operator inserted a guide catheter and easily passed a 0.014 inch floppy-tipped guidewire to the distal artery. A 2.5 mm by 20 mm long compliant balloon inflated at the occlusion site immediately restored TIMI-3 flow, and resulted in resolution of chest pain and ST-segment elevation. However, an extensive filling defect was observed, consistent with a large intracoronary thrombus (Figure 14-2 and Video 14-1). The operator passed a Pronto extraction catheter over the floppy-tipped guidewire to the distal artery and, using a 30 cc syringe, gently aspirated as the catheter was withdrawn to the guide catheter. A large amount of clot was successfully removed and improved the angiographic appearance of the artery with no evidence of distal embolization (Figure 14-3 and Video 14-2). A 4 mm diameter by 28 mm long bare-metal stent postdilated with a 4.5 mm noncompliant balloon successfully treated the residual stenosis (Figures 14-4, 14-5 and Video 14-3). At the completion of the procedure, the patient had no further chest pain and was transferred to the coronary care unit.

Discussion

Angiographic thrombus is most often encountered in patients undergoing an intervention for acute coronary syndromes. Visible clot often occurs in patients with ST-segment elevation infarction. Similarly, patients undergoing PCI for failed thrombolysis (i.e., rescue angioplasty), as demonstrated in this case, also are likely to have a large thrombus burden. The presence of visible clot is a high-risk feature and is associated with a higher rate of death, myocardial infarction, and abrupt vessel closure,1 and is also associated with other adverse angiographic outcomes such as failure to achieve TIMI-3 flow post-PCI for acute MI, development of no-reflow phenomenon, and distal embolization.

Adjunctive pharmacology helps reduce the risk of complication from PCI in the setting of visible thrombus. Antiplatelet agents are highly efficacious in this setting and both pretreatment with aspirin and clopidogrel and the adjunctive use of the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors are essential for success. Additionally, it is important to achieve an adequate antithrombin effect. If unfractionated heparin is used, the activated clotting time (ACT) should be at least within the therapeutic range (>200 seconds if a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor is used); some operators prefer higher levels (250 to 300 seconds) in the presence of a visible clot. Although anecdotal reports abound, the role of intracoronary glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors or intracoronary lytics has not been well established in a randomized controlled manner.2 Similarly, although bivalirudin is an effective antithrombin agent for PCI in the setting of acute myocardial infarction (especially if pre-loaded with clopidogrel), the efficacy of this agent without glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors for PCI in the setting of visible thrombus is unclear.

Numerous mechanical methods have been developed for physical removal of the thrombus. The more complex devices such as the rheolytic thrombectomy device (Angiojet) and an atherectomy-type device (X-Sizer catheter) have not been shown to be beneficial and may be associated with increased risk of adverse outcomes, likely due to distal embolization.3,4 Aspiration catheters are simply large-bore catheters that use manual aspiration with a syringe to remove clot. They are highly effective at removing clot and employ much simpler techniques and more limited device inventory than the more complex devices. Importantly, aspiration devices have been shown to improve outcomes when used routinely in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.5 Distal protection devices have not shown benefit when applied routinely to patients with STEMI;6 whether they are helpful in preventing distal embolization in patients with large, visible thrombus such as this case is unclear.

1 Singh M., Reeder G.S., Ohman E.M., et al. Does the presence of thrombus seen on a coronary angiogram affect the outcome after percutaneous coronary angioplasty? An angiographic trials pool data experience. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:624-630.

2 Kelly R.V., Crouch E., Krumnacher H., Cohen M.G., Stouffer G.A. Safety of adjunctive intracoronary thrombolytic therapy during complex percutaneous coronary intervention: initial experience with intracoronary tenecteplase. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2005;66:327-332.

3 Kelly R.V., Cohen M.G., Stouffer G.A. Mechanical thrombectomy options in complex percutaneous coronary interventions. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2006;68:917-928.

4 Ali A., Cox D., Dib N., et al. Rheolytic thrombectomy with percutaneous coronary intervention for infarct size reduction in acute myocardial infarction. 30-day results from a multicenter randomized study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:244-252.

5 Silva-Orrego P., Colombo P., Bigi R., et al. Thrombus aspiration before primary angioplasty improves myocardial reperfusion in acute myocardial infarction. The DEAR-MI (Dethrombosis to Enhance Acute Reperfusion in Myocardial Infarction) Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:1552-1559.

6 Stone G.W., Webb J., Cox D.A., et al. Enhanced myocardial efficacy and recovery by aspiration of liberated debris (EMERALD) Investigators: Distal microcirculatory protection during percutaneous coronary intervention in acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293:1063-1072.