CHAPTER 139

Osteoarthritis

Definition

Osteoarthritis (OA) is generally considered a family of degenerative joint disorders characterized by specific clinical and radiographic findings. OA is the most prevalent chronic joint disease and has become the most common cause of walking disability in older adults in the United States [1–3]. It is estimated that 26.9 million adults have clinical OA, and the total cost for all arthritis, including OA, is more than 2% of the United States gross domestic product [4,5]. The disease burden of OA is likely to continue to increase with the aging population and higher incidence of obesity [2,5].

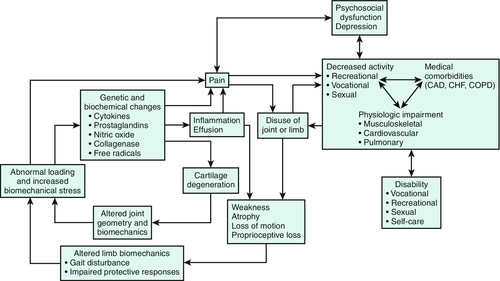

OA has traditionally been thought of as just a condition of cartilage degeneration [6]. It is actually a complex combination of genetic, metabolic, biomechanical, and biochemical joint changes that lead to failure of the normal cartilage remodeling process (Fig. 139.1). The joint then accumulates increasing cartilage degeneration changes in response to stress or injury [2,6]. More recent evidence implicates bone changes and synovial inflammation also as integral to the pathologic process of OA [2]. As a whole, OA is characterized by degradation and loss of articular cartilage, hypertrophic bone changes with osteophyte formation, subchondral bone remodeling appearing as sclerosis or cysts, and chronic synovitis or inflammation of the synovial membrane [1,6].

Joint involvement in OA is usually asymmetric, with a predilection for weight-bearing joints. Common sites of involvement are the hips, knees, hands, feet, and spine. Less common sites of involvement are the ankles, wrists, shoulders, and sacroiliac joints. Secondary arthritis may be manifested with an atypical pattern of joint involvement.

OA is classified into two groups: primary and secondary. Primary or idiopathic OA can be localized or generalized. Localized OA usually refers to a single joint; generalized OA describes involvement of three or more joints. Secondary OA is due to a specific condition known to cause or to worsen development of OA (Table 139.1).

Multiple risk factors have been linked to the development of OA (Table 139.2). Systemic factors include age, gender, genetics, bone mineral density, and body weight. Age is consistently one of the strongest if not the strongest risk factor for OA [3,5]. Female gender is associated with higher prevalence of symptomatic knee, hip, and hand OA [3,5]. Heritable genetic traits may play a role in OA, but identification of such traits has been challenging. Some genetic markers strongly implicated in OA include GDF5, MCF2L, and the genomic region 7q22 [7,8]. There is an inverse relationship between bone mineral density and OA [3,9]. Both overweight and obese people are shown to be at a greater risk for OA, especially in weight-bearing joints like the knee [3,10,11]. Low levels of factors like vitamin C, vitamin D, vitamin E, and vitamin K may have an effect on OA, but there is no consensus recommendation currently [3].

Local biomechanical factors implicated in OA include previous joint injury, joint malalignment, bone anatomic variation or abnormality, and muscle weakness. Those with previous injury have a 15% greater lifetime risk of symptomatic knee OA [11]. Lower extremity malalignment may be associated with greater radiographic knee OA. Bone abnormality like acetabular dysplasia is associated with greater incidence of hip OA [12]. Muscle weakness, specifically of the knee extensor muscles, predicts knee OA in most cohorts of women [3,13].

In terms of physical loading, some suggest that there is greater risk of knee OA with work activities such as squatting, lifting, prolonged standing, or climbing stairs, but this is not seen consistently [11]. Currently, there is no strong evidence to show that sports or physical activity itself leads to an increased risk of symptomatic OA [3]. Historical data have correlated certain sports with OA of specific joints, but there are many confounders in these studies that make interpretation inconclusive [3].

Symptoms

Patients usually complain of pain, stiffness, reduced movement, and swelling in the affected joints that is exacerbated with activity and relieved by rest. Pain at rest or at night suggests severe disease or another diagnosis. Early morning stiffness, if it is present, is typically less than 30 minutes. Joint tenderness and crepitus on movement may also be present. Swelling may be due to bone deformity, such as osteophyte formation, or an effusion caused by synovial fluid accumulation. Systemic symptoms are absent.

In early disease, pain is usually gradual in onset and mild in intensity. Pain is typically self-limited or intermittent. Patients with advanced disease may describe a sense of grinding or locking with joint motion and buckling or instability of joints during demanding tasks. Periarticular muscle pain may be prominent. Patients may complain of fatigue if biomechanical changes lead to increased energy requirements for activities of daily living. Overuse of alternative muscle groups can lead to development of pain syndromes in other parts of the musculoskeletal system.

Physical Examination

Joint Examination

Diagnosis of OA involves assessment of the affected joints for common clinical features (Table 139.3). These usually include tenderness, bone enlargement, and malalignment. Osteophytes, joint surface irregularity, or chronic disuse may also result in decreased range of motion, pain, effusion, and crepitus. Locking during range of motion may suggest loose bodies or floating cartilage fragments in the joint. Joint contracture can result from holding a joint in slight flexion, which is less painful for inflamed or swollen joints. There may be secondary abnormalities in joints above or below the primarily involved joint. Remember to assess joints bilaterally because asymptomatic joints may also have abnormal findings.

Neuromuscular and General Examination

A thorough musculoskeletal examination should include inspection, palpation of soft tissues surrounding the joint of interest, assessment of muscle strength and flexibility, and joint-specific provocative maneuvers. First, gait should be observed. There may be an antalgic gait or a slow gait pattern because of pain in a specific joint. If the patient uses a cane, appropriate use of the cane should be assessed during gait.

Both functional strength and manual muscle testing should be performed. Periarticular muscle atrophy and weakness may be present in chronic OA. However, manual muscle testing is typically unreliable in the lower extremities because of the high baseline strength of these muscle groups. Function tests like sit-to-stand testing may be more informative. Palpation and dynamic testing of soft tissues may differentiate pain from tendinopathy or bursitis from OA. Joint-specific provocative maneuvers may help isolate the source in symptomatic patients with poorly localized pain. A careful neurologic examination should be performed to ensure that pain is not the result of nerve impingement or a neuropathic process.

Clinicians may also consider performing a general examination. Evaluation of other systems may also help differentiate primary OA from secondary OA due to a systemic process. Because obesity has been identified as a risk factor for OA, assessment of the patient’s body mass index may also be useful.

Functional Limitations

Functional limitations will depend on the joints affected by OA. Patients with disease in the hips and knees will have impairments in mobility, locomotion, and activities of daily living involving the lower body. Patients may complain of increasing difficulty with climbing up and down stairs, walking, making chair or toileting transfers, and lower body dressing and grooming. Degeneration in the shoulders or hands limits vocational and recreational activities, self-care, and upper body activities of daily living. Patients may initially have trouble with using the computer or lifting boxes, which then progresses to difficulties with activities of daily living like feeding, grooming, bathing, and dressing. Spine OA can result in limitations with all mobility.

Diagnostic Studies

Although imaging studies are not needed to confirm the diagnosis, plain radiographs may help elucidate the severity of joint damage and progression of OA. The classic findings include asymmetric joint space narrowing, osteophytes at joint margins, subchondral sclerosis, and subchondral cyst formation. There is a well-demonstrated discordance between x-ray findings and symptoms in OA. Asymptomatic individuals may have significant radiographic disease, and severe pain and dysfunction can occur in the setting of limited radiologic changes. Computed tomography scans, ultrasonography, and magnetic resonance imaging are typically not needed for evaluation of OA but can be helpful in providing better visualization not only for OA severity evaluation but also for identification of other tissue pathologic processes and diagnosis [1].

Routine laboratory test results should be normal, and laboratory testing is usually not needed in uncomplicated cases of OA. If laboratory tests are available, clinicians should take care in interpreting the results. There is a high prevalence of laboratory abnormalities in elderly people, such as a raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate or anemia, because of comorbid conditions. Autoimmune markers may be useful to differentiate OA from other musculoskeletal disorders like inflammatory arthritides.

Joint aspiration should be pursued in patients with significant joint effusion or inflammation. Joint fluid analysis can be helpful in ruling out crystal deposition disease like gout or pseudogout, inflammatory arthritis, or infectious arthritis. In contrast to other arthritides, synovial fluid in OA is usually clear with normal viscosity and leukocyte counts typically less than 1500 to 2000 cells/mm3.

Treatment

Initial

The major principles of OA management involve relieving pain and other symptoms as well as maximizing joint function and quality of life. Initial treatment should include both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic rehabilitation modalities. Here we provide a broad overview of major concepts. Site-specific management of OA is discussed in more detail in other chapters.

No pharmacologic intervention has been shown conclusively to alter disease progression in OA. A number of topical and oral medications have been used to alleviate symptoms and to improve functional status. Topical treatment of OA includes nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), capsaicin, rubefacients, and opioids. Many treatment guidelines from 2008 or later recommend topical NSAIDs as first-line OA treatment, especially in elderly patients, in whom drug safety and tolerability are significant concerns [1,14,15]. In a meta-analysis of 7688 participants in 34 studies, topical NSAIDs were significantly more effective than placebo in treating chronic musculoskeletal conditions such as OA [16]. Topical diclofenac is the only NSAID approved for use by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Studies of topical diclofenac in OA indicate a number needed to treat of 6.4 to 11 for at least 50% pain relief during 8 to 12 weeks compared with placebo [16]. Topical NSAIDs are recommended over oral NSAIDs by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) for treatment of hand OA in patients older than 75 years [15].

Topical capsaicin cream has also been shown to reduce pain in joints affected by OA. This derivative of cayenne pepper causes exuberant release and depletion of substance P, which diminishes pain transmission from C fibers. Limited data from controlled trials have shown improvements in OA pain with capsaicin, and its use is recommended by the ACR and Osteoarthritis Research Society International as an adjunct or additional treatment [14,15].

Topical rubefacients containing salicylate or nicotinate esters are available for treatment of musculoskeletal pain without a prescription. They are thought to produce counterirritation and vasodilation of the skin for pain relief. Although they may be efficacious in the treatment of acute musculoskeletal pain in the short term (1 week), research on effectiveness is limited [17]. The ACR conditionally recommends trolamine salicylate as treatment of hand OA [15].

One randomized placebo-controlled trial looked at the use of transdermal fentanyl in moderate to severe OA [18]. Although there may be some pain relief, use of transdermal opioids is not routinely recommended because of the potential negative effects of opioid use [18–20].

Oral agents often discussed in the treatment of OA include acetaminophen, NSAIDs, opioids and opioid-like medications, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, and glucosamine and chondroitin. Acetaminophen and NSAIDs are typically considered first-line oral agents [1,14,15]. A meta-analysis of acetaminophen demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in pain compared with placebo in seven randomized controlled trials with a number needed to treat of 4 to 16 [21]. Although NSAIDs are more efficacious than acetaminophen, effects were modest and associated with greater rates of adverse gastrointestinal effects [21].

Tramadol acts not only as a weak opioid but through modulation of serotonin and norepinephrine levels. A meta-analysis of 11 randomized controlled trials with a total of 1019 patients showed less pain intensity, greater symptom relief, and improved function for those receiving some form of tramadol compared with placebo or control. However, adverse effects were often noted to cause patients to stop taking the medication [22]. Tramadol alone or in combination with acetaminophen is conditionally recommended by the ACR as initial treatment of OA in several joints [15].

The use of opioid medications in OA has risen. Although opioids can improve pain and function in patients with OA, there is a high rate of adverse events and withdrawal of patient treatment [1,20]. Opioids should be considered second-line treatment at best, even when OA pain is severe [20]. The ACR strongly recommends use of opioids only for patients who are either not willing to undergo or have contraindications to total knee arthroplasty after medical therapy has failed [15].

Duloxetine is a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor that is conditionally recommended by the ACR for treatment of knee OA [15]. In pooled data from two randomized controlled trials, patients with knee OA treated with duloxetine were more likely to experience an improvement in outcomes, pain, and function with a number needed to treat of 5 to 9 [23].

Significant attention has focused on the use of supplements such as chondroitin and glucosamine in OA. The Glucosamine/chondroitin Arthritis Intervention Trial (GAIT), a randomized controlled trial of 1583 patients with painful knee OA, demonstrated no clinically significant effective pain reduction [24]. Multiple other randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses of both chondroitin and glucosamine have had conflicting conclusions, and the topic is still hotly debated [1,25–27]. The ACR conditionally recommends against the use of chondroitin and glucosamine in knee OA and hip OA [15]. Patients considering the use of glucosamine or chondroitin should be cautioned that these products are not subject to regulation of purity or accuracy of labeling.

Other treatments of OA include avocado soybean unsaponifiables and diacerein, but these are not widely used [1].

Rehabilitation

A comprehensive rehabilitative approach is important and effective in promoting wellness and reducing disability in patients with OA.

Self-management interventions and programs foster active participation of patients and are thought to be a key element of chronic disease management [1]. These programs provide education and experiential skills in not only disease management but mental and social well-being. Studies have demonstrated that these interventions reduce pain, improve health behaviors, and reduce use of health care resources in patients with chronic pain and arthritis [28]. Group-based self-management programs are often available through a local chapter of the Arthritis Foundation and are conditionally recommended by the ACR for patients with hip and knee OA [15].

Lifestyle changes like exercise and weight loss are an integral part of rehabilitation of OA. There is significant evidence that physical activity is important in patients with OA. Both aerobic and muscle strengthening exercises seem to be beneficial in terms of improving pain, function, and quality of life [29–32]. A meta-analysis of 32 studies indicates platinum level [33] of evidence that land-based therapeutic exercises have at least short-term benefit for reduction of pain and improved physical function for knee OA [34]. There is silver level [33] of evidence for land-based therapeutic exercises for reduction of pain and improvement of physical function in symptomatic hip OA [35]. Therapeutic exercises should include joint protection techniques, stretching and range of motion exercises, muscle strengthening, and aerobic exercises.

Weight loss is important in overweight patients with OA. A meta-analysis of weight reduction in patients with knee OA showed diminished physical disability with a weight loss of more than 5% within a 20-week period [36].

The ACR strongly recommends land-based cardiovascular (aerobic) and resistance exercises, aquatic exercises, Tai Chi, and weight loss (in persons overweight) for patients with OA of hip and knee [15]. Physiatrists, occupational therapists, physical therapists, and other health care professionals can help make recommendations on appropriate exercise, weight loss techniques, and therapeutic modalities for individualized patient care.

Clinical experience suggests that cold, heat, and manual therapy can be helpful in decreasing pain and increasing mobility. Thermal agents and manual therapy in combination with supervised exercise are also recommended by the ACR [15].

Braces and splints may be helpful for symptomatic relief of certain joints. Knee bracing had additional benefit compared with medical treatment alone on the basis of limited evidence [37]. Splints may be useful for OA of the thumb [38]. The ACR recommends splinting for patients with hand OA, specifically of the trapeziometacarpal joint, but offers no recommendations on knee bracing [15].

Orthotic wedged insoles and medially directed patellar taping may be helpful for knee OA to off-load the joint or to improve biomechanics.

Adaptive equipment, such as a cane or walker, can be used if necessary for patients with impaired balance to prevent falls or for pain reduction by decreasing joint loading. In the setting of significant functional impairments, therapists can provide assistive devices that help with feeding, grooming, dressing, and other activities of daily living.

The use of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation is supported by a few small, short-term trials. Systematic review of the data has been inconclusive [39]. For most patients in these studies, pain relief was experienced only during active use of the device. Regardless, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation is conditionally recommended by the ACR in knee OA [15]. Ultrasound appears to have no proven benefit in the treatment of OA.

Acupuncture is also recommended for the treatment of chronic moderate to severe painful knee OA. A multicenter, 26-week National Institutes of Health–funded randomized controlled trial found acupuncture to be effective as adjunctive therapy for reducing pain and improving function in patients with knee OA [40]. A meta-analysis of acupuncture in the treatment of OA showed statistically significant benefits compared with sham or waiting list controls [41].

Procedures

Intra-articular corticosteroid injection is conditionally recommended by the ACR for patients with painful knee or hip OA who do not have a satisfactory clinical response to full-dose acetaminophen [15]. The short-term effect of intra-articular corticosteroid injection has been well demonstrated in meta-analysis, and it is routinely used in treatment of OA [42,43]. There is clinically significant improved pain relief and patient global assessment compared with placebo injections, although the effects typically last only 1 to 3 weeks [42,43].

Intra-articular hyaluronic acid injections (viscosupplementation) are conditionally recommended by the ACR for people 75 years of age or older with knee OA but are not routinely recommended for OA of other joints [15]. Although conflicting evidence exists, multiple meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials suggest that there may be a small benefit in comparison with intra-articular placebo injection or noninterventional control [43,44]. The clinical significance is difficult to determine and may be irrelevant. In comparison with glucocorticoid injections, hyaluronic acid injections had greater benefit between 5 and 13 weeks after injection, but this was not sustained [43].

Procedures such as botulinum toxin type A injection, intra-articular injection of platelet-rich plasma, and adipose stem cell injections are under investigation [42,45–48]. A few studies showed positive effect of platelet-rich plasma in patients with knee OA, but no standardized protocol has been established [47,48].

Surgery

In patients for whom pain and loss of mobility are disabling despite conservative management, orthopedic consultation should be obtained to assess risks and benefits of surgery.

Surgical interventions performed for OA include arthroscopic lavage and débridement, osteotomy, joint fusion, joint distraction, and arthroplasty. Joint replacement surgery or total joint arthroplasty is a mainstay of surgical OA treatment. Protocols for total joint arthroplasty include different approaches and minimally invasive techniques. A systematic review of hip replacement surgery trials concluded that in 70% of subjects, pain and function scores were rated good or excellent 10 years postoperatively [49]. Observational studies have suggested that better outcomes are associated with patients between the ages of 45 and 75 years; with weight less than 70 kg; and with a good social support, higher educational level, and lower preoperative morbidity [50]. Similar favorable results have been achieved in total knee replacement for OA. In both hip and knee joint replacements, early inpatient rehabilitation after arthroplasty has been shown to reduce hospital stays and cost of care in older patients with medical comorbidities [51].

Systematic review of arthroscopic lavage and débridement in OA showed no short- or long-term benefit compared with placebo, and it is not advised [52]. Osteotomy has been used to correct biomechanics and to unload areas of high stress with some success. Fusion may be helpful in situations in which joint replacement is not appropriate. Joint distraction or distraction arthroplasty is increasingly performed for ankle OA to avoid fusion and to maintain range of motion. Hip joint resurfacing is an effective alternative to total arthroplasty in severe hip OA [53], but patellar resurfacing is not recommended in knee pain, for which no benefit has been shown [54].

Potential Disease Complications

Potential complications of OA include chronic pain, muscle weakness, decreased range of motion, limited physical function, inability to participate in work or the community, and loss of self-care skills.

Potential Treatment Complications

The safety profile of topical OA medications is generally good. Topical NSAIDs may cause increased local adverse events (mostly mild skin reactions) compared with placebo or oral NSAIDs [16]. However, topical NSAIDs have decreased incidence of gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, and renal adverse events compared with traditional oral NSAIDs [15,16]. Topical capsaicin and rubefacients are known for local skin reactions like redness, burning pain, and itching. It is worthwhile to caution patients that they may experience increased pain when beginning therapy.

Oral analgesics including acetaminophen and NSAIDs have well-known side effects that most commonly affect the gastric, hepatic, and renal systems. Although use of acetaminophen is associated with only mild side effects for the most part, it does carry a significant risk of hepatic toxicity. NSAIDs are known to have both gastrointestinal toxicity and nephrotoxicity and are associated with increased risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, and erectile dysfunction. In patients with high gastrointestinal risk for ulceration and bleeding, a cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor or NSAID with concurrent use of a proton pump inhibitor may be considered [1]. Selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors carry greater cardiovascular risk and should be used only in patients with minimal cardiovascular risk factors and no history of cardiovascular disease. The most common adverse drug reactions of tramadol and opioids are nausea, vomiting, itching, sweating, constipation, and drowsiness. Drug addiction and dependence with both are widely reported.

All intra-articular injections usually have mild side effects but, like any procedure, may result in bleeding, infection, and local irritation and pain. Complications common to all surgical techniques include pain, bleeding, infection, and effects of anesthesia. Studies have well documented the adverse effects or events associated with total arthroplasty. Intraoperative complications include fracture, nerve injury, vascular injury, and cement-related hypotension. Postoperative complications of total joint arthroplasty include thromboembolism, dislocation, osteolysis, aseptic loosening, implant failure or fracture, and heterotopic ossification. Aseptic loosening, implant failure, and fractures are often painful and require surgical revision.