CHAPTER 133

Movement Disorders

Definition

Involuntary movement disorders can be characterized by either too little (hypokinetic) or too much (hyperkinetic) movement. Hypokinetic problems include Parkinson disease and Parkinson-like conditions, such as progressive supranuclear palsy, vascular or trauma-induced parkinsonism, and multisystem atrophy (which encompasses the related disorders of Shy-Drager syndrome, striatonigral degeneration, and olivopontocerebellar degeneration). Hyperkinetic disorders include parkinsonian and nonparkinsonian tremor, tics, Gilles de la Tourette syndrome, dystonia, dyskinesias (including tardive dyskinesias), hemifacial spasm, athetosis, chorea (including Huntington disease), hemiballismus, myoclonus, and asterixis [1].

Essential tremor, the most common movement disorder, is 5 to 10 times more prevalent than Parkinson disease in the general population. Parkinson disease affects 1 million Americans including 1% of those older than 60 years. Idiopathic Parkinson disease constitutes approximately 85% of all the Parkinson-like conditions; neuroleptic-induced Parkinson disease (7%-9%), vascular parkinsonism (3%), multisystem atrophy (2.5%), and progressive supranuclear palsy (1.5%) represent much smaller fractions. Relatively rare, Huntington disease occurs with a frequency in the population as low as 0.004% by some estimates [2,3].

Symptoms

Tremors, the most common form of involuntary movement disorders, are characterized by rhythmic oscillations of a body part. Tremors can be classified as to the situation in which they are most prominent, that is, most pronounced at rest or with movement. Tremors with movement are subdivided into those occurring with maintained posture (postural or static tremor, tested by holding the arms out in front), with movement from point to point (kinetic or intentional tremor, tested by finger to nose pointing), or with only a specific type of movement (task-specific tremor). Tremors that are at their worst at rest are exclusively associated with Parkinson disease or other parkinsonian states (such as those produced by neuroleptics) [2,4].

Parkinsonian patients commonly show a resting tremor, slowness of movement or bradykinesia, and a form of increased muscle tone called rigidity (see Chapter 141 for more details). Other common features are reduction in movements of facial expression resulting in “masked facies,” stooped posture, and reduction of the amplitude of movements (hypometria). Also seen are changes in speech to a soft monotone (hypophonia) and small, less legible handwriting (micrographia). Walking becomes slower, stride length is reduced, and pivoting is replaced with a series of small steps (turning “en bloc”) [5,6]. The nonmotor symptoms associated with Parkinson disease can be equally disabling: fatigue, pain, and neuropsychiatric disturbances, among others [3]. The following syndromes typically are manifested with the listed features in addition to the characteristic symptoms of Parkinson disease (tremor and rigidity) [7].

• Shy-Drager syndrome: autonomic failure with prominent postural hypotension

• Progressive supranuclear palsy: reduction in vertical gaze and slowing of eye movements

• Vascular parkinsonism: early dementia with brisk tendon reflexes

• Multiple head trauma, “parkinsonism pugilistica”: early dementia with brisk tendon reflexes

• Olivopontocerebellar degeneration: prominent intention tremor, imbalance, and ataxia

Tics are sustained nonrhythmic muscle contractions that are rapid and stereotyped, often occurring in the same extremity or body part during times of stress. The muscles of the face and neck are usually involved, with movement of a rotational sort away from the body’s midline. They are commonly familial and often seen in otherwise normal children between the ages of 5 and 10 years and usually disappear by the end of adolescence. Tourette syndrome is characterized by motor and vocal tics lasting for more than 1 year and may involve involuntary use of obscenities and obscene gestures, although such behavior may be mild and transient and occurs only in a minority of afflicted persons [6,8].

Dystonias are slow, sustained contractions of muscles that frequently cause twisting movements or abnormal postures. The disorder resembles athetosis but shows a more sustained static contraction. When rapid movements are involved, they are usually repetitive and continuous. Dystonia often increases with emotional or physical stress, anxiety, pain, or fatigue and disappears with sleep. The dystonias are further classified as focal, segmental, or multifocal on the basis of the distribution of muscles affected. Symptoms of hemifacial spasm usually begin in the orbicularis oculi and later involve other muscles innervated by cranial nerve VII [1,6,9].

Tardive dyskinesia is a condition characterized by involuntary, choreiform movements of the face and tongue associated with chronic neuroleptic medication use. Common movements include chewing, sucking, mouthing, licking, “fly-catching movements,” puckering, and smacking (buccal-lingual-masticatory syndrome). Choreiform movements of the trunk and extremities can also occur along with dystonic movements of the neck and trunk.

Athetosis is characterized by involuntary, slow, writhing, and repetitious movements. They are slower than choreiform movements and less sustained than dystonia. Athetosis may be seen alone or in combination with other movement disorders and itself leads to bizarre but characteristic postures. Any part of the body can be affected, but it is usually the face and distal upper extremities that are involved. Chorea is manifested as nonstereotyped, unpredictable, and jerky movements that interfere with purposeful motion. The movements are rapid, erratic, and complex and can be seen in any or all body parts but usually involve the oral structures, causing abnormal speech and respiratory patterns. Hemiballismus is an uncommon disorder consisting of extremely violent flinging of the arms and legs on one side of the body.

Myoclonus is one of the most common involuntary movement disorders of central nervous system origin. It is characterized by sudden, jerky, irregular contractions of a muscle or groups of muscles. It can be subdivided into stimulus-sensitive myoclonus (reflex myoclonus), appearing with volitional movement, muscle stretch, or superficial stimuli such as touch, and non–stimulus- sensitive myoclonus, which occurs at rest (spontaneous myoclonus). Myoclonic movements can be either irregular or periodic [1,6].

Physical Examination

A complete physical examination is key to ruling out treatable causes of the presenting movement disorder, such as infectious (encephalitis), medication side effect (tardive dyskinesia), genetic (Tourette syndrome), or endocrinologic (tremor-associated thyrotoxicosis).

A good neurologic examination of patients thought to have a movement disorder helps identify an underlying causative condition, such as stroke (e.g., cerebrovascular-based Parkinson disease, hemiballismus, or ataxia), tumor, brain trauma, or even peripheral nerve injury–associated focal dystonias. Other aspects of physical examination focus on characterization of the type of abnormal movements by detailing of their body distribution (limb, trunk, head, face, or widespread), their quality (tremor, writhing, explosive, rigidity), their frequency (rapid and repetitive or slow and sustained), and their general quantity or lack thereof (hyperactive or hypoactive).

For instance, essential tremor (senile tremor) is usually rapid and fine and occurs when the patient is asked to hold the arms outstretched, whereas parkinsonian tremor decreases with voluntary movement. Intention (cerebellar) tremor is slow and broad, occurring at the end of a purposeful motion, as when the patient executes a finger to nose task. In addition to tests of cerebellar function, tests for upper motor neuron syndrome (hyperreflexia, spasticity, presence of Babinski sign) may assist the examiner in distinguishing movement disorders more commonly associated with stroke or brain injury.

Functional Limitations

Functional limitations depend on the severity of the movement disorder. Some tremors and tics may be more a cosmetic and psychological concern, whereas severe postural disturbance in Parkinson disease or stroke-induced ataxia can clearly impair ambulation or upper extremity control. In Parkinson disease, postural changes, such as stooping with the development of permanent kyphosis, can occur after years of disease. Many physical activities require additional effort to be performed. Manual dexterity is invariably impaired as Parkinson disease worsens, affecting many daily activities, such as dressing, cutting food, writing, and handling small objects such as coins [10]. Soft, monotone, hoarse voice quality and imprecise articulation, together with restricted facial expression (masked facies), contribute to limitations in communication in a large majority of individuals with Parkinson disease, with 30% reporting it the most debilitating deficit. These functional losses negatively affect quality of life, leading to declining efficiency at work and, in many cases, abandonment of many leisure activities. Depression and social isolation are commonly seen in patients with Parkinson disease.

In cervical dystonia (torticollis), social stigmatization is a major concern, as are functional impairments, which can include driving, reading, and activities that involve looking down and using the hands. In another focal dystonia, writer’s or occupational cramp, the symptoms are manifested in a certain posture or position; for instance, a patient may be able to write at a blackboard but not seated at a desk. With lingual involvement in oromandibular dystonia, the tongue has abnormal movements during speaking or deglutition. The result of such dystonias is impairment of speech and eating [9]. In Huntington chorea, along with the choreiform movement, progressive dementia and emotional and behavioral abnormalities are seen. As the disease progresses, the presentation becomes less choreiform and more parkinsonian and dystonic (i.e., restricted motions, immobility, and unsteadiness of gait). Intellectual impairment and psychosis invariably occur and progress rapidly to become the most disabling features [6].

Diagnostic Studies

In most cases of movement disorders, such as Parkinson disease, tardive dyskinesia, essential tremor, and dystonia, the diagnosis is made on the grounds of clinical examination and history; no one specific test is pathognomonic for the disease [5–7]. Positron emission tomography and single-photon emission computed tomography scans are able to identify altered brain dopaminergic activity; however, their superiority over clinical diagnosis is unclear at this time [6]. Evaluation for potential causes of the other movement disorders, such as stroke, traumatic brain injury, normal-pressure hydrocephalus, tumor, infection, and metabolic or endocrinologic disease, should be performed with appropriate tests, including head and spinal magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography, cerebrospinal fluid analysis, and blood serum analysis. Electrodiagnostic tests (electromyography and nerve conduction studies) may be useful in some cases, such as focal dystonias, to rule out coexisting or causative peripheral nerve entrapment. Electroencephalography is often helpful in distinguishing focal seizures from myoclonus or other repetitive movement presentations [11]. More tests may be necessary to confirm or to exclude other diagnoses, such as human immunodeficiency virus–related diseases, central nervous system infection, toxic exposures, Wilson disease, and psychiatric illnesses. Videofluoroscopy should be ordered to more accurately characterize swallow dysfunction and to assist with treatment planning when the clinical examination findings or symptoms suggest dysphagia.

Treatment

Initial

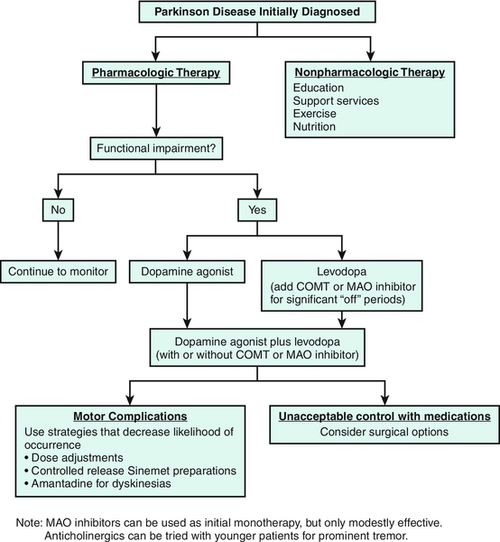

Treatment is highly dependent on which specific category of movement disorder is present. Typically, pharmacologic treatment is initiated when the symptoms become severe enough to cause discomfort or disability (Fig. 133.1).

Antiparkinson medications replace dopamine (levodopa), act as a postsynaptic (dopamine) agonist, increase the availability of levodopa or dopamine by preventing their metabolism (catechol-O-methyltransferase, monamine oxidase B inhibitors), or reestablish the dopamine-acetylcholine balance in the striatum (anticholinergics). Levodopa in combination with carbidopa (Sinemet) continues to be the most effective medication for treatment of Parkinson disease symptoms, but it is usually not the first medication given to those newly diagnosed, particularly in younger patients. The dopamine agonists bromocriptine (Parlodel), ropinirole (Requip), and pramipexole (Mirapex) or the recently approved rotigotine (Neupro) transdermal patch can be used as monotherapies in mild, early Parkinson disease, as can the monamine oxidase B inhibitors selegiline (Eldepryl, Zelapar) and rasagiline (Azilect). Loss of levodopa efficacy usually develops within 3 to 5 years after the medication is begun, so an effort is made to manage early Parkinson disease with other medications. A guiding principle is to start levodopa treatment in patients with symptoms that interfere with the performance of daily life functions despite other treatment. Its long-term use is associated with the development of motor fluctuations and dyskinesias. Over time, as the disease worsens, the patient’s frequency of levodopa dosing and the total dose needed will increase, along with the need for other supplemental medications, such as the dopamine agonists and monamine oxidase B inhibitors, to help counter worsening motor fluctuations [12]. For patients with significant “off time,” the catechol-O-methyltransferase inhibitors entacapone (Comtan) and tolcapone (Tasmar) are used in combination with levodopa/carbidopa, slowing its breakdown and augmenting its effectiveness. Because hepatic disease has been reported with tolcapone use, liver function test monitoring is required.

Anticholinergic drugs such as trihexyphenidyl (Artane) and benztropine (Cogentin) are used less widely today because of their side effect profile and limited efficacy for rigidity and bradykinesia. They are useful primarily for younger patients with tremor as their primary symptom [3,5,6,12,13].

A continuous pump-based infusion of levodopa/carbidopa directly into the small intestines through an implanted catheter has shown efficacy in Parkinson disease patients suffering motor fluctuations and is presently undergoing clinical trials the United States [14].

Propranolol is the most useful medication in treating essential tremor (the most common symptomatic tremor), task-specific tremor, and action tremor. Other beta blockers have fewer side effects but are less effective. The anticonvulsant primidone and the benzodiazepine clonazepam are also effective antitremor drugs. Gabapentin and botulinum toxin injections may be of some benefit in tremor management [1,2,6]. Tics can be managed with neuroleptics; pimozide and haloperidol are generally effective, but sedation limits their use. Newer atypical neuroleptics may have fewer side effects, including risperidone, quetiapine, olanzapine, and clozapine. Other medications shown to be of some benefit include clonazepam, clonidine, calcium channel blockers, and antidepressant agents [1,6]. Anticholinergic medications, such as trihexyphenidyl and benztropine, are the most effective oral agents for both generalized and focal dystonias in younger patients. Baclofen (either orally or by intrathecal pump), carbamazepine, and the benzodiazepines, such as diazepam and clonazepam, are sometimes helpful. Dopamine-blocking or dopamine-depleting agents may be used to treat some patients with dystonia. Focal dystonias are now commonly treated with botulinum toxin injections [6,9] (see the section on procedures).

Replacement of typical antipsychotic drugs with the atypical neuroleptics, such as clozapine and risperidone, is useful to control psychosis in patients with tardive dyskinesia without worsening of symptoms. Other drugs, such as benzodiazepines, adrenergic antagonists, and dopamine agonists, may also be beneficial for suppression of the movements. The most important step in the treatment of tardive dyskinesia is prevention by limiting the use of neuroleptic medications [15]. The response to drug therapy has been poor in patients with ataxia; many agents have been touted as useful (propranolol, isoniazid, carbamazepine, clonazepam, tryptophan, buspirone, thyroid-stimulating hormone), but none has demonstrated efficacy [16]. A number of drugs have been used to treat myoclonus and can be effective in some situations. These include diazepam, clonazepam, valproate, and levetiracetam (Keppra) as well as botulinum toxin injections [11].

Rehabilitation

In general, the patient with Parkinson disease needs to be counseled to maintain a reasonable level of activity at all costs as physical exertion becomes more difficult and the risk of deconditioning increases. Exercises focus on proper body alignment (upright posture) and postural reflexes (response to dynamic balance challenges) as well as on limb range of motion and strengthening of proximal musculature to assist in stair climbing and coming to a stand. Exercises are also aimed at the restoration of diminished reciprocal limb motions and an increase in step length and can include treadmill training. A number of randomized studies in Parkinson disease patients have demonstrated benefits such as improved walking speed and endurance, step length, and balance with several forms of exercise [17,18].

The tendency to freeze can be reduced with visual targets, such as markers on the floor, counting, or marching rhythmically. The difficulty in rising from sitting surfaces can be addressed with elevated sitting surfaces (chair, toilet) and strategically placed grab rails or bars (bed, bathtub). Although wheeled walkers are useful in assisting ambulation, particularly by preventing backward instability, patients with significant postural deficits may prefer more stable devices, such as a supermarket shopping cart or walking behind a wheelchair. Adaptive equipment is provided when deficits in upper extremity control limit efficient and safe function [19,20]. Speech therapy is useful in patients with Parkinson disease to improve articulation and loudness as well as to diagnose and to manage dysphagia [13,21].

In tremor, measures to reduce or to alleviate anxiety (e.g., biofeedback, relaxation exercises) are useful, as are strategies to control oscillation excursion with weights or other mechanical compensations [20]. Lifestyle changes may include restriction of caffeine intake or other stimulants that may temporarily augment symptoms. In addition, alcohol consumption may lead to transient improvement for many with essential tremor [2,6].

Stretching exercises may be important for maintenance or recovery of range of motion for affected joints in a dystonic limb. Certain types of occupation-based focal limb dystonias (e.g., writer’s or musician’s cramp) may be treated with muscle reeducation techniques, including biofeedback. A regular program of stretching exercises may assist affected individuals in regaining full range of motion after a botulinum toxin injection has weakened a dystonic muscle. Some patients use so-called sensory tricks to temporarily relieve their symptoms. These commonly involve touching or stroking a particular spot on the skin. In addition, in some patients, certain types of braces may provide the same stimulation and be equally effective [14,20].

Ataxic patients may benefit from rehabilitation to help them learn compensatory techniques for performance of basic self-care and occupational activities and to assess the benefits of weighted bracelets or similar devices to damp the oscillations. Gait training and education in the use of assistive devices for walking can prevent falls and enhance mobility in the ataxic individual. In disorders involving athetosis, ballismus, or Huntington disease, careful weighting of the extremities can help at times. Rehabilitation techniques involving improvement of coactivation and trunk stability, rhythmic stabilization, and traditional relaxation techniques including biofeedback have been mentioned as reasonable strategies. Some have suggested value in oral desensitization when hyperreactivity to sensory stimuli exists for reducing excessive facial movements in tardive dyskinesia, but other rehabilitation strategies are not of proven utility [20].

Procedures

Botulinum toxin injections are beneficial in numerous hyperkinetic movement disorders, including focal dystonias, tremor, and myoclonus. Trigger point injections may provide relief in painful muscles associated with focal dystonias (e.g., cervical torticollis).

The muscles selected for botulinum toxin injection are based on understanding of the primary clinical patterns of spasticity or dystonia. Direct injection by palpation technique may be appropriate for superficial muscles; electromyography or electrical stimulation guidance is commonly used to identify deeper muscles. Each muscle is injected in one or more sites, the number being a function of the size of the muscle. Dosage is variable but typically does not exceed 400 units total body dose for a 3-month period. Botulinum toxin A is reconstituted in the vial with preservative-free normal saline, at varying dilutions depending on the muscle size. For example, an average size muscle, such as flexor carpi radialis, could receive a concentration of 10 units per 0.1 mL.

The skin is cleaned with an alcohol or iodine swab and allowed to dry. When electromyography or electrical stimulation guidance is used, a specialized needle with an exposed tip connected by wire to the recording or stimulating device is needed. Needles are typically 37 mm in length and 27-gauge; larger or smaller needles are often needed, depending on muscle size and depth. In adults, pre-anesthetization of the skin is usually unnecessary; in children, local anesthetic creams are helpful. When botulinum toxin is injected, aspiration of the syringe to prevent injection into a blood vessel is standard technique. Before the injection, informed consent is obtained.

For Parkinson patients, cell transplants and gene therapies continue as experimental procedures still under investigation [13].

Surgery

Deep brain stimulation (subthalamic nuclei, globus pallidus) has been proven efficacious and has largely replaced neuroablative lesion procedures, such as thalamotomy and pallidotomy, for Parkinson disease [1,6,22]. Both deep brain stimulation and ablative surgery are also used for severe cases of other movement disorders, such as tremor or dystonia. In addition, peripheral destructive procedures, such as myectomy, rhizotomy, and peripheral nerve denervation, are occasionally performed on individuals with dystonic limbs who have proved refractory to more conventional management.

Potential Disease Complications

Many of the movement disorders, particularly Parkinson disease, are progressive and can result in muscle weakness and immobility, severe limb contractures, aspiration of food and respiratory compromise, social isolation and depression, and intellectual impairment and dementia.

Potential Treatment Complications

Antiparkinson medications may have numerous side effects, including nausea and other gastrointestinal symptoms, drowsiness, confusion, hallucinations, psychosis, and motor dyskinesia. Similar adverse medication effects are described with other agents used to suppress unwanted movements. Botulinum toxin is generally well tolerated but can cause transient unwanted weakness in target or adjacent muscles, including dysphagia. Risks associated with surgical approaches to central nervous system structures are considerable and need to be properly weighed before these options are selected [1,6,22].