CHAPTER 13 Family Therapy

OVERVIEW

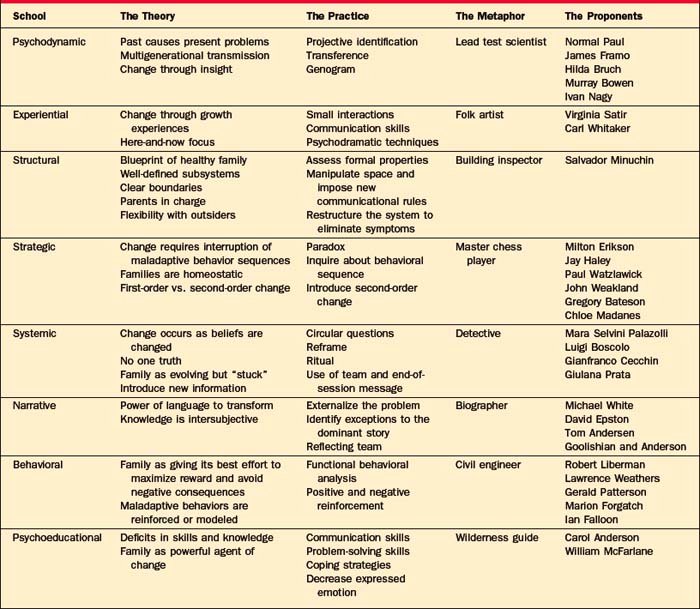

Family therapy has a rich array of approaches; to highlight them we will present a clinical vignette and illustrate how eight different types of family therapists would approach family problems.1 For each school of family therapy (Table 13-1), the major theoretical constructs, a practical approach to the family, the major proponents of that school, and a metaphor that captures something essential about that type of family therapy will be discussed. The vignette revolves around a composite family with an anorectic member. The focus is on family dynamics rather than on anorexia per se, but anorexia has been paradigmatic to family therapy, much as hysteria was for psychoanalysis or borderline personality disorder was for dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT).

PSYCHODYNAMIC FAMILY THERAPY

The Practice

In order to loosen the grip of the past on the present, the therapist uses several tools (including interpretation of transferential objects in the room, interpretation of projective identification, and the use of the genogram to make sense of generational transmission of issues). In family therapy, transferential interpretations are made among family members, rather than between the patient and the therapist, as occurs in individual therapy. For example, when Mr. Bean says “I guess I am not an expert when it comes to female problems,” the therapist may have asked, “Who made you feel that way in your family of origin?” When he reveals that he has felt this way since his sister’s suicide, he comes to understand how an old lens distorts his current vision (i.e., he still feels so guilty about his sister’s death that he does not feel entitled to weigh in with opinions about his daughter’s anorexia).

Another important tool for dredging up the past is the interpretation of projective identification, which Zinner and Shapiro2 have defined as the process “by which members split off disavowed or cherished aspects of themselves and project them onto others within the family group.” This process generates intrapsychic peace at the expense of interpersonal conflict. For example, Mrs. Bean may disown her need to control her impulses by projecting her perfectionism onto Pam. Simultaneously, Pam can disown her anger by enraging her parents with her anorexia. As these unconscious projections occur reflexively, they are more difficult for the individual to recognize and to own. Put another way, each family member behaves in such a way as to elicit the very part of the self that has been disavowed and projected onto another family member. The purpose of these mutual projections is to keep old relationships alive by the reenactment of conflicts that parents had with their families of origin. Thus, when Mrs. Bean projects her perfectionism onto Pam, she re-creates the conflict she had with her own mother, who lacked tolerance of impulses that were not tightly controlled.

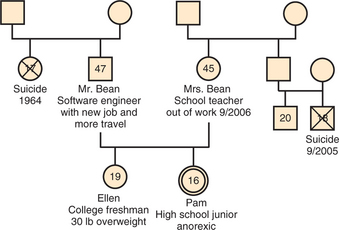

In part, the psychodynamic family therapist gathers and analyzes multigenerational transmission of issues through the use of a genogram (Figure 13-1), a visual representation of a family that maps at least three generations of that family’s history. The genogram reveals patterns (of similarity and difference) across generations—and between the two sides of the family involving many domains: parent-child and sibling roles, symptomatic behavior, triadic patterns, developmental milestones, repetitive stressors, and cutoffs of family members.2

In addition, the genogram allows the clinician to look for any resonance between a current developmental issue and a similar one in a previous generation. This intersection of past with present anxiety may heighten the meaning and valence of a current problem.3 With the Bean family (including two adolescents), the developmental imperative is to work on separation; this is complicated by the catastrophic separations of previous adolescents. Their therapist might discover a multigenerational pattern of role reversals, where children nurture parents, as suggested by the repetition of failed attempts of adolescents to separate from their parents.

The Proponents

James Framo4 invites parents and adult siblings to come to an adult child’s session; this tactic allows the past to be revisited in the present. This “family of origin” work is usually brief and intensive, and consists of two lengthy sessions on 2 consecutive days. The meetings may focus on unresolved issues or on disclosure of secrets; it allows the adult child to become less reactive to his or her parents.

Norman Paul5 believes that most current symptoms in a family can be connected to a previous loss that has been insufficiently mourned. In family therapy, each member mourns an important loss while other members bear witness and consequently develop new stores of empathy.

Ivan Boszormenyi-Nagy6 introduced the idea of the “family ledger,” a multigenerational accounting system of obligations incurred and debts repaid over time. Symptoms are understood in terms of an individual’s making sacrifices in his or her own life in order to repay an injustice from a previous generation.

Murray Bowen7 stressed the dual importance of the individual’s differentiation of self, while maintaining a connection to the family. In order to promote increased independence, Bowen coached patients to return to their family of origin and to resist the pull of triangulated relationships, by insisting that interactions remain dyadic.

EXPERIENTIAL FAMILY THERAPY

The Practice

This therapist uses psychodramatic, or action-oriented, techniques to create a new experience in the therapy session. She or he might “sculpt” the family, literally posing them to demonstrate the way that the family is currently organized—for example, with mother and Pam sitting very close together, with Mr. Bean with his back to them, and with Ellen outside of the circle. This therapist would hope to heighten feelings of frustration and alienation, and then to relieve those feelings with a new sculpture that places the parents together. These sculptures would serve to increase affect, to create some focus away from the identified patient, and to demonstrate the merits of the parents who are standing together to combat their daughter’s anorexia.

The Proponents

Virginia Satir,8 an early luminary in family therapy (a field that was largely founded by men), believed that good communication depends on each family member feeling self-confident and valued. She focused on what was positive in a family, and used nonverbal communication to improve connections within a family. If families learned to see, to hear, and to touch more, they would have more resources available to solve problems. She is credited with the use of family sculpting as a means to demonstrate the constraining rules and roles in a family.

Carl Whitaker9 posited that most experience occurs outside of awareness; he practiced “therapy of the absurd,” a method that accesses the unconscious by using humor, boredom, free association, metaphors, and even wrestling on the floor. Symbolic, nonverbal growth experiences followed, with an aim toward the disruption of rigid patterns of thought and behavior. As Whitaker puts it, “psychotherapy of the absurd can be a deliberate effort to break the old patterns of thought and behavior. At one point, we called this tactic the creation of process koans” (p. 11)9; it is a process that stirs up anxiety in family members.

STRUCTURAL FAMILY THERAPY

The Proponents

Salvador Minuchin,10,11 regarded as the founding father of structural family therapy, worked extensively while head of the Philadelphia Child Guidance Clinic with inner-city families and with families who faced delinquency and multiple somatic symptoms. Both populations had not previously been treated with family therapy. He delineated how to assess and to understand the existing structure of a family, and pioneered techniques such as the imposition of rules of communication, manipulation of space, and use of enactments to modify structure.

STRATEGIC FAMILY THERAPY

The Proponents

Milton Erikson12 (whose focus on behavioral change relied on indirect suggestion through the use of stories, riddles, and metaphors) has heavily influenced this school. Strategic therapists have borrowed this reliance on playful storytelling techniques. The California Mental Research Institute (MRI) family therapists, including Jay Haley, Paul Wazlawick, John Weakland, and Gregory Bateson, were the earliest proponents of strategic family therapy. They encouraged therapists to look to the role of power in the therapeutic encounter, since families usually make paradoxical requests, for example, “Get us out of this mess but don’t make us change.”

Chloe Madanes13 assumed that when children act out, their symptoms represent efforts to help the family. However, along with helping the family, the child’s symptoms also reverse the generational hierarchy, placing the child in a position that is superior to that of his or her parents. Consequently, Madanes advocated using paradoxical techniques to reassert the parents’ authority. For example, she might invite the parent to ask the child to pretend to help out or to pretend to have the problem. In both instances, these strategies put the parents back in charge, while allowing the child a playful means of being helpful.

SYSTEMIC FAMILY THERAPY

The Theory

The systemic family therapist believes that change occurs when beliefs are changed or the meaning of behavior is altered. In this view, the solutions, as well as the power to change, lie within the family. This therapist rejects the notion that the therapist holds a clear idea of what the family should look like at the end of successful treatment. The therapist does not presume to know the right truth to help a family. Instead, this therapist holds that there is no one truth; rather, some ideas are more useful than others.

The systemic therapist introduces new information in an effort to bring about systemic change. When Bateson14 wrote that information is “news of a difference,” he meant that we only register information that comes from making comparisons. He and other systemic therapists use circular questions, which are aimed at surfacing differences around time, perception, ranking on a characteristic, and alliances within a family. Linear questions (e.g., “What made you depressed?”) ask family members about cause and effect. Circular questions (e.g., “Who is most concerned about mother’s depression? Then who? Then who?”), by contrast, take a problem and place it within the web of family relationships. Other circular questions (e.g., “Who in the family is the most concerned about Pam?” “When were things different in the family, when you weren’t worried about Pam?”) attempt to elicit hidden comparisons and useable information.

A ritual is introduced, not as a behavioral directive, but as an experiment.15 This therapist does not care if the ritual is carried out exactly as prescribed, since it is the ideas contained in the ritual that contain the power to change. When families enact two inconsistent behaviors simultaneously, a ritual can introduce time into this paradoxical system. With the Beans, the therapist might be struck by the ways that Mr. and Mrs. Bean treat Pam simultaneously as both a young girl and a young woman, undermining each other’s position so that the parents are never on the same page at the same time. This therapist might suggest the following “odd-even day” ritual: “On Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, we would like you to regard Pam as a little girl who can’t manage basic functions (such as eating). On Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday, we’d like you to think about Pam as a young woman who is getting ready to leave home.” The parents are given the opportunity to collaborate on a shared view of their daughter at the same time, first as a girl, then as a young woman.

Rituals and reframes were usually introduced at the conclusion of a five-part meeting with a team of therapists and a family.16

The Practice

At the outset, this therapist, working either with or without a team, generates a few hypotheses to be confirmed or discounted using circular questions.17 One hypothesis is that Pam’s anorexia serves to keep her parents distracted from their own marital conflicts, which might escalate if they didn’t have Pam to worry about. For example, the following circular questions could be asked: “If in five years Pam has graduated from college and is of normal weight, what would your relationship as parents be like?” “Who is most worried about Pam?” “If you weren’t worried about Pam, where would that energy go?”

NARRATIVE FAMILY THERAPY

The Theory

These therapists use story in two significant ways: first, to deconstruct, or to separate, problems from the people who experience them; and then to reconstruct, or to help families rewrite, the stories that they tell about their lives. These complementary processes of deconstruction and reconstruction are exemplified in the technique of externalizing the problem.18 With this technique, the therapist and the family create a name for the problem and attribute negative intentions to it so that the family can band together against the problem, rather than attack the individual who has the problem. The therapist subsequently asks about “unique outcomes,” or times when the patient was free of the problem. The family is asked to wonder what made it possible at those times to find the strength to resist the pull of the problem. In time, these unusual moments of resistance are amplified and added to by more stories that feature the patient as competent and problem free.

Narrative therapists have also developed the concept known as the reflecting team, to aid in the treatment of families and the training of therapists.19,20 With this approach a group of clinicians observe an interview through a one-way mirror, and then speak directly to the family, offering ideas, observations, questions, and suggestions.21 These comments are offered tentatively and spontaneously so that the family can choose what is useful from among the team’s offerings and reject the rest. Several narrative assumptions form the underpinning of the reflecting team22: the abundance of ideas generated by the team will help loosen a constricted story held by the family; the relationship between the therapist and the patient should be nonhierarchical (with an emphasis placed on sharing rather than on giving information); people change under a positive connotation; and there are no right or wrong ideas, just ones that are more or less helpful to a family.

The Practice

This therapist might begin by asking the Beans how they would know when the therapy was over. More specifically, he or she might ask the De Shazer miracle questions,23 “If there were a miracle that took place overnight and Pam were no longer anorectic, what else would be different? How would the family be different? How would each of you be interacting with her?”

The Proponents

Michael White, in Australia, and David Epston, in New Zealand, are the best-known thinkers and writers of the narrative approach.24 In addition to their ideas of deconstructing the problem through externalizing and reauthoring, they have emphasized the political and social context in which all clinical work occurs. Relying on the work of Foucault, they critique the professional’s linkage of power and knowledge. For example, they do not make diagnoses or rely on medical records kept private from their patients. Instead, they may write a letter to a patient at the end of the session and use the same letter as the clinical note for the medical record. At the close of therapy, the record may be given to the patient or, with permission, shared with other patients who are struggling with similar difficulties.

The invention of the reflecting team is credited to Tom Andersen and his colleagues at the Tromso University in Norway in 1985. Observing the interview from behind the mirror, Andersen found that the therapist continued to follow a pessimistic view of the family, regardless of the reframing questions that were phoned in by the team. Finally, after several attempts to redirect the interview were thwarted, he “launched the idea to the family and the therapist that we might talk while they listened to us.”25 With the team speaking directly to the family, presenting multiple ideas in an unrehearsed way, the concept of the reflecting team took root.

BEHAVIORAL FAMILY THERAPY

The Theory

Behavioral family therapy26–28 derives from social learning theory, with particular attention paid to demonstrating empirical evidence for interventions. In this model, family systems represent members’ best attempts to achieve personal and mutual rewards while avoiding negative consequences. In order for maladaptive behaviors to endure, they must be modeled or reinforced somewhere within the system. The therapist and the family will collaborate in an effort to identify behavioral patterns and sequences that are problematic. The therapist then employs varied, empirically supported behavioral techniques to promote the learning of new adaptive behaviors while extinguishing their problematic predecessors.

The Practice

Ultimately, a hypothesis is generated as to the way each problematic behavior might be reinforced and what interventions might result in its extinction. The Bean family would be encouraged to choose specific goals. The therapist then acts as a collaborator and teacher, designing experiments that will test for behavioral changes. These will often be in the form of homework, but can also be conducted within the session. The results of these experiments will be analyzed with the same rigor of the initial assessment in order to assure all that they are proving objectively beneficial. Techniques include contingency contracting (Mr. and Mrs. Bean make reciprocal commitments to exchange positive regard for each other daily) and other operant reinforcement strategies (Mrs. Bean praises Pam’s partial completion of meals, and does not comment on what is left over). Behavioral family therapy techniques have established empirical support across a broad range of conditions,29–37 both as individual interventions and as adjuncts to other treatment modalities.

The Proponents

Robert Liberman38 and Lawrence Weathers39 have made major contributions to the field of behavioral family therapy, including their application of contingency contracting. This form of operant conditioning recognizes that families in distress tend to have an increase in aversive exchanges marked by negative affect. In the contingency contract, family members agree to undertake structured interactions designed at improving positive exchanges. Gerald Patterson,40 along with Marion Forgatch,41 has explored the way family systems reinforce aggressive behavior in adolescents. The reinforcement is characterized by intermittent punishment, empty threats, and parental irritability. Falloon and Liberman’s42 attention to levels of expressed emotion within families has informed both the behavioral and psychoeducational schools of family therapy.

PSYCHOEDUCATIONAL FAMILY THERAPY

The Theory

Psychoeducational family therapy26–28 originated to assist families caring for a member with severe mental illness and functional impairment. The therapist understands family dysfunction as deficits in acquirable skills and knowledge. Through education and focused skills training, families and patients are empowered to effect their own change. The therapist anticipates deficiencies in several key domains. These include communication, problem solving, coping, and knowledge of the illness. The therapist is also vigilant in identifying relationships that appear overinvolved or hypercritical, because these are associated with an increased likelihood of relapse and exacerbations of the affected member’s illness. The goal of therapy is to create an environment that is more deliberate in its fostering of mastery and recovery.

The Proponents

Psychoeducational family therapy finds its origins in the treatment of schizophrenia. Carol Anderson43 developed a psychoeducational model for schizophrenia, which she later adapted to affective disorders. William McFarlane44 is responsible for the psychoeducational model illustrated in the previous example, which also was designed for families coping with schizophrenia. In his model, several families with schizophrenic members meet together for psychoeducation. Psychoeducational methods are finding continued empirically supported applications for schizophrenia,45 as well as conditions outside of the formal thought disorders,46 and will likely continue to expand to additional diagnoses and contexts.

THE MAUDSLEY MODEL: AN EXAMPLE OF THEORY INTEGRATION

The Maudsley model of family-based treatment for anorexia nervosa in adolescents represents a powerful integration of all schools into a single, manualized, empirically supported32 method. This model is an example of two current trends in the field of family therapy: integration, rather than strict adherence to one theory,47,48 and a move toward demonstrable research evidence for treatment efficacy.49

The first phase is single-minded in its pragmatic ultimate purpose: weight gain. In the first session, the Bean family is greeted warmly, and the therapist reviews Pam’s current weight, the realities of the threat to her life, and key concepts fundamental to the illness, such as Pam’s preoccupation with her body. Basic physiological effects of starvation, such as hypothermia and cardiac dysfunction, are explained in a manner understandable to the entire family. Externalization of the problem, reminiscent of the narrative school, is employed from the outset, and anorexia, rather than Pam or her family, is to be blamed for Pam’s current state. The therapist models and reinforces noncritical behaviors and attitudes toward Pam and every other member of the family. High expressed emotion is discouraged.

CONCLUSION

The field of family therapy has tended to value the distinctiveness of its different models50—the founding mothers and fathers of family therapy were typically dynamic mavericks who called attention to how different they were from individual psychotherapists and from each other. The growth of the field has not been driven by research, but rather by innovative theory and creative technique.

While there have been no research studies comparing the efficacy of each of the major schools, many studies have looked at process variables and outcome measures within the behavioral29,30,32,35–37 and psychoeducational44,45 models. Shadish and colleagues,51 summarizing their extensive meta-analysis of marital and family therapy, conclude that “no orientation is yet demonstrably superior to any other” (p. 348). The most effective approaches tend to be multidisciplinary or integrative, such as the Maudsley model. More studies are needed to determine whether there are common factors that account for therapeutic change, regardless of the theoretical model. As with individual therapy, Sprenkle and colleagues52 posit that the following factors likely account for most of the change that transpires during family therapy: client factors, such as higher socioeconomic status, the shared cultural background between client and therapist,53 and the family’s ability to mobilize social supports; relationship factors, particularly the presence of warmth, humor, and positive regard in the therapeutic relationship54; and the family therapist’s ability to engender hope and a sense of agency in family members.

1 Fishel A. Treating the adolescent in family therapy: a developmental and narrative approach. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson, 1999.

2 Zinner J, Shapiro S. Projective identification as a mode of perception and behavior in families of adolescents. Int J Psychoanal. 1972;53:523-530.

3 McGoldrick M, Gerson R. Genograms in family assessment. New York: Norton, 1985.

4 Framo J. Family of origin as therapeutic resource for adults in marital and family therapy. Fam Process. 1976;15:193-210.

5 Paul N. The role of mourning and empathy in conjoint marital therapy. In: Zuk G, Boszormenyi-Nagy I, editors. Family therapy and disturbed families. Palo Alto, CA: Science and Behavior Books, 1969.

6 Boszormenyi-Nagy I. Invisible loyalties. New York: Harper & Row, 1973.

7 Bowen M. Family therapy in clinical practice. New York: Jason Aronson, 1978.

8 Satir V. Conjoint family therapy. Palo Alto, CA: Science and Behavior Books, 1964.

9 Whitaker C. Psychotherapy of the absurd. Fam Process. 1975:1-16.

10 Minuchin S. Families and family therapy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1974.

11 Minuchin S, Bernice R, Baker L. Psychosomatic families: anorexia in context. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1978.

12 Erikson MH, Rossi EL. Experiencing hypnosis: therapeutic approaches to altered states. New York: Irvington, 1981.

13 Madanes C. Strategic family therapy. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1981.

14 Bateson G. Mind and nature. New York: E. P. Dutton, 1979.

15 Imber-Black E, Roberts J. Rituals in families and family therapy. New York: Norton, 1988.

16 Tomm K. One perspective on the Milan systemic approach: part II. Description of session format, interviewing style and interventions. J Marital Fam Ther. 1984;10(3):253-271.

17 Penn P. Circular questioning. Fam Process. 1982;21(3):267-280.

18 White M: The externalizing of the problem and the reauthoring of lives and relationships, Dulwich Centre Newsletter, Summer 1988.

19 Friedman S, editor. The reflecting team in action. New York: Guilford Press, 1996.

20 Andersen T. The reflecting team: dialogue and meta-dialogue in clinical work. Fam Process. 1987;26:415-428.

21 Fishel A, Ablon S, McSheffrey C, Buchs T. What do couples find most helpful about the reflecting team? J Couple Relationship Ther. 2005;4(4):23-37.

22 Miller D, Lax WD. Interrupting deadly struggles: a reflecting team model of working with couples. J Strategic Systemic Therapies. 1988;7(3):16-22.

23 De Shazer S. Words were originally magic. New York: Norton, 1994.

24 White M, Epston D. Narrative means to therapeutic ends. New York: Norton, 1990.

25 Andersen T. Reflecting processes: acts of informing and forming. In: Friedman S, editor. The reflecting team in action. New York: Guilford Press, 1996.

26 Scholvar GP, Schwoeri LD, editors. Textbook of family and couples therapy: clinical applications. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2003.

27 Lebow J, editor. Handbook of clinical family therapy. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2005.

28 Carr A. Family therapy: concepts, process and practice. Baffins Lane, England: John Wiley & Sons, 2000.

29 Birmaher B, Brent DA, Kolko D, et al. Clinical outcome after short-term psychotherapy for adolescents with major depressive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:29-36.

30 Barrett PM, Healy-Farrell L, March JS. Cognitive behavioral family treatment of childhood obsessive-compulsive disorder: a controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:46-62.

31 Cobham VE, Dadds MR, Spence SH. The role of parental anxiety in the treatment of childhood anxiety. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66:893-905.

32 Robin AL, Siegel PT, Loepke T, et al. A controlled comparison of family versus individual therapy for adolescents with anorexia nervosa. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38:1482-1489.

33 Sanders MR, Markie-Dadds C, Tully LA, et al. The triple P—positive parenting program: a comparison of enhanced, standard, and self-directed behavioral family intervention for parents of children with early onset conduct problems. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68(4):624-640.

34 Bor W, Sanders MR, Markie-Dadds C. The effects of the Triple P—Positive Parenting Program on preschool children with co-occurring disruptive behavior and attentional/hyperactive difficulties. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2002;30(6):571-587.

35 Waldron HB, Slesnick N, Brody JL, et al. Treatment outcomes for adolescent substance abuse at 3- and 7-month assessments. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:802-813.

36 Epstein LH, McCurley J, Wing RR, et al. Five-year follow-up of family-based behavioral treatments for childhood obesity. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1990;58(5):661-664.

37 Gustafsson PA, Kjellman NI. Family therapy in the treatment of severe childhood asthma. J Psychosom Res. 1986;30(3):369-374.

38 Liberman RL. Behavioral approaches to family and couple therapy. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1970;40:106-119.

39 Weathers L, Liberman RL. Contingency contracting with families of delinquent adolescents. Behav Ther. 1975;6:356-366.

40 Patterson G A social learning approach to family intervention: coercive family processes;vol 3; 1982, Castalia Eugene, OR.

41 Patterson G, Forgatch M. Parents and adolescents living together, vol 1, The basics. Eugene, OR: Castalia, 1987.

42 Falloon IR, Liberman RL. Behavioral therapy for families with child management problems. In: Textor MR, editor. Helping families with special problems. New York: Jason Aronson, 1981.

43 Anderson CM, Hogarty GE, Reiss DJ. Family treatment of adult schizophrenic patients: a psychoeducational approach. Schizophr Bull. 1980;6:490-505.

44 McFarlane W, Family psycho-educational treatment Gurman AS, Kniskern DP, editors. Handbook of family therapy, vol 2. New York: Bruner/Mazel, 1991.

45 Dyck DG, Short RA, Hendryx MS, et al. Management of negative symptoms among patients with schizophrenia attend-ing multiple-family groups. Psychiatric Services. 2000;51(4):513-519.

46 Long P, Forehand R, Wierson M, et al. Does parent training with young noncompliant children have long-term effects? Behav Res Ther. 1994;32:101-107.

47 Fraenkel P, Pinsof W. Teaching family-therapy centered integration: assimilation and beyond. J Psychother Integration. 2001;11(1):59-85.

48 Lebow J. The integrative revolution in couple and family therapy. Fam Process. 1997;36:1-18.

49 Lock J, Le Grange D, Agras WS, Dare C. Treatment manual for anorexia nervosa: a family-based approach. New York: Guilford Press, 2001.

50 Shields GC, Wynne LC, McDaniel SH, Gawinski BA. The marginalization of family therapy: a historical and continuing problem. J Marital Fam Ther. 1994;20:117-138.

51 Shadish WR, Ragsdale K, Glaser RR, Montgomery LM. The efficacy and effectiveness of marital and family therapy: a perspective from meta-analysis. J Marital Fam Ther. 1995;21:345-360.

52 Sprenkle DH, Blow A, Dickey M. Common factors and other nontechnique variables in marriage and family therapy. In: Hubble MA, Duncan BL, Miller SD, editors. The heart and soul of change: what works in therapy. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 1999.

53 Goldstein MJ, Miklowitz DJ. The effectiveness of psychoeducational family therapy in the treatment of schizophrenic disorders. J Marital Fam Ther. 1995;21:361-376.

54 Alexander JF, Barton C, Schiavo RS, Parsons BV. Systems-behavioral intervention with families of delinquents: therapist characteristics, family behavior, and outcome. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1977;44:656-664.