IDENTIFYING THE PROBLEM

The ageing of the population and advances in medical technology have combined to create a problem in making some decisions about medical treatment. In particular, the issues arise with end-of-life situations when a person, because of a disability, lacks the capacity to exercise their autonomy by consenting to or refusing medical treatment. Rothschild refers to the ‘medicalisation of death’ in concluding that: ‘The law lacks consistency and clarity, not having evolved with the same momentum as medical science and patient rights’ (Rothschild 2007).

Too often there is a lack of clarity surrounding the treatment decisions that are taken on behalf of people who lack capacity and this can be particularly troubling when end-of-life decisions are involved. Problems can arise from the level of understanding of the law on the part of medical practitioners, the extent to which clinical decisions over-ride other factors, uncertainty in the process of determining the best interests of the patient, the role of family members and the managing of disputes. Too often, it appears that the outcome is the provision of treatment that the patient, if competent, would not have agreed to.

The fact that the population is ageing is well established. For example, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) in the 4 years to 2006 while the number of Victorians under the age of 60 was projected to increase by 2.8% those over the age of 80 was projected to increase by 19.1% (ABS, unpublished, 2002). Ageing does not by itself, of course, inevitably affect a person’s capacity to make an informed decision about their own medical treatment. However, ageing statistics assume far greater significance when placed with data on the incidence of dementia. Over the age of 60 years the prevalence of dementia doubles every 5 years of age. Estimates of the proportion of persons affected at the age of 85 range from 24% (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2007) to 32% (Access Economics 2003).

Among the advances in medical technology are those that have the effect of sustaining life in circumstances in which a person would previously have died. Paradoxically, fewer difficulties seem to arise with life-sustaining technical equipment. Extubation is commonplace and, while such decisions are undeniably difficult, they are less problematic than ceasing the provision of medical treatment in the form of artificial nutrition and hydration.

This treatment, often referred to as enteral feeding, can be administered on an ongoing basis using a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG). A tube is surgically inserted into the stomach when patients have difficulty swallowing as a result of injury or disease. This, relatively simple, form of medical technology has only been available for about 25 years. Doctors Gauderer and Ponsky, the physicians credited with inventing the PEG tube in 1979, did so for the purpose of treating children. They did not envision PEG feeding being used for end-of-life care. Ponsky (2005) is quoted as saying, ‘It never entered our minds this would produce such a massive ethical dilemma’.

The causes of the dilemma of which Dr Ponsky speaks are many. Arguably, it arises in part because of human reactions. Consumers of health services are more able to comprehend the notion of feeding in comparison to the abstruse intricacies of other medical treatments. There is something far more emotionally difficult about ceasing to provide food and water than there is about switching off highly technical life support machines. Perhaps it is because people with a disability are compared in their degree of dependency to newborn infants who are totally dependent on others for food and water, or as Riet et al. (2006 p 183) suggest:

The provision of medically administered nutrition and hydration for the terminally ill patient is indeed a controversial issue. Eating and drinking are basic to our survival, and in society food has symbolic overtones involving nurturing as well as religious, cultural and social values. The giving of food and drink is an act of love, steadfastness, compassion and hospitality.

The dilemma is compounded by those who claim that removing PEG feeding is inhumane as it results in a painful and slow death from thirst and starvation. Such comments not infrequently come from proponents of euthanasia who argue that there should be a positive act to bring about a quick and painless death. Even Ponsky (2005) has observed:

We take convicted murderers and give them a gentle death by injection and we take someone like Terri Schiavo and decide she has to die and make her suffer weeks of dehydration and malnutrition and loss of dignity rather than provide a rapid euthanasia. It’s a paradox.

While more problems arise as the population ages, younger patients have publicised the issue. Cases such as Schiavo in the US and Korp in Victoria demonstrate this.

Terri Schiavo suffered brain damage as a result of a heart attack. She was sustained by PEG feeding – and other excellent nursing care – for a period of 15 years until her death in March 2005. During that time the rights and wrongs of ceasing treatment were debated within her family, the media, the general public, and in courts. The dilemma her treatment presented would not have arisen two decades before.

The same dilemma about ceasing enteral feeding arose with Mrs Korp.1 Her condition was described as one of post-coma unresponsiveness (PCU), a term preferred in Australia to that of ‘vegetative state’, which was used previously and is still used elsewhere. It is defined by the National Health and Medical Research Council (2003) as being applied:

… to patients emerging from coma in an apparently wakeful unconscious state in which there is:

- a complete lack of responses that suggest a cognitive component;

- preservation of sleep-wake cycles and cardiorespiratory function; and

- partial or complete preservation of hypothalamic and brain stem autonomic functions.

- preservation of sleep-wake cycles and cardiorespiratory function; and

While decisions were made about removing Mrs Korp’s tracheostomy, whether to aggressively treat infections, not to return her to the intensive care unit (ICU), and not to use cardiopulmonary resuscitation, the critical remaining decision was whether or not to cease to provide artificial nutrition and hydration.

The treating clinical team had the power to cease treatment (other than palliative care) that was futile, overly burdensome and not in Mrs Korp’s best interests. However, they were deterred by the media interest arising from the circumstances leading to her injuries and the contemporaneous death of Terri Schiavo. Comparisons were inevitably made between the two cases despite significant clinical differences. Further, decision making was complicated by the public statement of Mrs Korp’s husband, who had been charged with her attempted murder, that he would oppose in court any attempt to cease treatment. He argued that his wife, as a devout and practising Catholic, would want treatment continued indefinitely.

Consequently, the Public Advocate2 became the guardian of last resort following an application by the hospital to the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal (VCAT). The principal question for the tribunal was who was suitable to be the guardian. Her husband had a conflict of interest, her daughter declined the onerous responsibility and other family members were rejected. The decision to appoint the Public Advocate illustrated the importance of the protective legislation in ensuring that a substitute decision maker is able to act solely in the best interests of the person with a disability.

Powers given to the guardian included the making of decisions about medical treatment. While it was clear that enteral feeding did, within Victorian law, constitute medical treatment and could therefore be refused, this had not always been the case. An earlier dilemma for medical practitioners in Victoria had been the vexed question of whether it constituted medical treatment (which could be refused) or whether it constituted ‘palliative care’ (which could not be refused or withdrawn). It was a question that had caused problems since the passing of the Victorian Medical Treatment Act 1988.

The dilemma was resolved by the Victorian Supreme Court in the case of Mrs BWV (Gardner 2003). Mrs BWV, who was aged 69 and suffering dementia, had been unresponsive for 3 years and appeared to have no cognitive capacity. Her general practitioner, who was providing excellent care, believed he had no choice other than to continue providing enteral feeding.

The court held that PEG feeding was medical treatment and could therefore be refused by the guardian on behalf of Mrs BWV (provided that certain conditions required by the Act were met). While the decision deals with Victorian law, its application might be wider. Skene (2004) considers that it will be followed elsewhere in Australia while other commentators have urged health policy makers to incorporate the court’s findings in both practice and policy in Australia (Mendelson & Ashby 2004).

The guardian for Mrs Korp could therefore lawfully decide to withdraw treatment, provided doing so was in her best interests. An investigation to inform that decision included reviewing the tests and clinical observations upon which medical advice was based, her prognosis, the options for treatment, and the risks associated with all options. In addition to written reports, numerous meetings were held with various specialists, including neurologists, physicians and palliative care specialists, as well as with nursing staff. At these meetings the medical opinions were questioned and tested.

The investigation also centred on ascertaining Mrs Korp’s wishes and values. Enquiries were made of family, friends, work colleagues, neighbours and her priest. It was concluded that there was no evidence of her having expressed views or wishes about medical treatment. It was also concluded that she was a devout and practising Catholic.

Clinical advice indicated that Mrs Korp’s condition was continuing to deteriorate and that despite periods of stability at a lower level than before, it had not been possible to achieve ongoing stability. Despite maximal artificial nutrition and hydration she was continuing to lose weight and her muscles were wasting, leading to severe contractions of her limbs and difficulties in maintaining a number of internal functions. Treatment other than palliative care was futile.

Under Victorian law a guardian can refuse medical treatment if it causes unreasonable distress or if it is considered that the person themselves, if competent and fully informed, would have considered it unwarranted. Given the level of controversy the latter element was explored by applying the medical facts to a statement by the former Pope on the issue of withdrawing nutrition (Pope John Paul II 2004). A Catholic priest, expert in ethics, was consulted and agreed that withdrawal was consistent with this statement.

A decision was made to withdraw treatment other than palliation and Mrs Korp died within 9 days, after almost 15 weeks in hospital. One factor that was not considered relevant by the guardian was that of the cost to the medical system of ongoing treatment. Any hospital faced with such a situation would find that the contentiousness of the decision would impose large cost pressures even though the clinical view was that the treatment was not warranted.

THE POLICY RESPONSES

The first observation that should be made is that the Australian legal system has addressed this problem reasonably effectively by providing a mechanism for resolving most issues about withdrawal of life support treatment decisions. It has done so in a way that is relatively inexpensive and quick.

It has for centuries been the duty of the state to protect incompetent citizens (in this case, adults) from exploitation, abuse and neglect. While Supreme Courts can discharge this duty and have powers concurrent with the Public Advocate or his equivalent in other jurisdictions, in practice they leave these matters to a guardian appointed by a tribunal. While in other types of cases guardians can frustrate hospital administrators by insisting on investigating options before agreeing to a discharge, in Korp’s case guardianship operated to the benefit of the health system. This was by deflecting criticism from the hospital, by providing it with clear legal authority to act, and by doing so relatively quickly.

Many factors differentiated the cases of Korp and Schiavo, including the stark contrast between the one guardianship tribunal hearing in Korp and the case of Schiavo, where there were many. These:

… included fourteen appeals and numerous motions, petitions, and hearings in the Florida courts; five suits in Federal District Court; Florida legislation struck down by the Supreme Court of Florida; a subpoena by a congressional committee in an attempt to qualify Schiavo for witness protection; federal legislation (Palm Sunday Compromise); and four denials of certiorari from the Supreme Court of the United States.

While a guardian was appointed in both cases, in Schiavo’s case it was the husband himself. In contrast, in Korp’s case the tribunal had the option of appointing an independent statutory officer and declined to appoint potentially partial family members. In the UK contentious decisions of this nature involve applications to a superior court. For example, in the case of Anthony Bland (a young man who suffered brain injury in the collapse of the Hillsborough soccer stadium) it was the House of Lords that ultimately decided that treatment in the form of PEG feeding could be withdrawn (Bland 1993).

The Australian policy response to the problem of contentious withdrawal of treatment decisions is comparatively pragmatic. Tribunals are accessible and relatively inexpensive: courts are rarely involved. Given the federal nature of Australia, the relevant laws vary from state to state.3 Generally, decision making is placed in the hands of a guardian, as it is in Victoria. In NSW, while this has been believed to be the position, clarification is currently needed as a result of a tribunal finding that a decision to withdraw dialysis was beyond the power of the Public Guardian (WK 2006). In Queensland, a number of the decisions authorising the withdrawal of treatment have been made by the Guardianship and Administration Tribunal. For example, the tribunal held, in a case with facts reminiscent of those of BWV, that PEG feeding should be withdrawn from an 80-year-old woman said to be in a persistent vegetative state (MC 2003).

The problem of withdrawing treatment has also stimulated a response from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) in relation to the cohort of patients who, like Mrs Korp, are diagnosed as being in a state of PCU. The NHMRC established a working committee to prepare draft ethical guidelines to be considered by the Australian Health Ethics Committee about the care of persons with PCU, or in a minimally responsive state. It distributed an issues paper in April 2006 (NHMRC 2006).

It is to be hoped that the ethical guidelines ultimately to be produced by the NHMRC will provide positive assistance for clinicians and allied professionals when confronted with decisions about continuing treatment for this group of patients. It is possible that the guidelines might assist in other clinical situations, such as those involving dementia, which have in common the lack of capacity in a patient to decide whether they will or will not consent to the medical treatment that is being offered to them.

Complexities for health professionals will continue, however, when the degree of capacity is not clear. Balancing the rights to autonomy and to treatment can be fraught, for example, when the choices being exercised by the individual do not coincide with the clinician’s own views about what is in that person’s best medical interests. The law relating to capacity itself further complicates the situation in its complexity and uncertainty. This has been recognised by the Attorney General’s Department in NSW which issued a discussion paper that canvassed not only the need for changes in the law but also in the practice of assessing capacity (Attorney General’s Department NSW 2006).

There is a further way in which the response of Australian courts to these issues has supported the health system. Ceasing treatment is often problematic when family members are opposed to, or cannot bring themselves to accept, the clinical view that further treatment is futile and should not be offered. The implications of such situations can be significant when scarce resources, such as the ongoing occupation of an ICU bed, are an issue. Whether this problem has been compounded by the laudable shift towards a less autocratic style of dispensing medical treatment or whether it reflects a fear of adverse publicity or litigation is not clear. Courts have supported clinicians by consistently refusing to intervene and to require the provision of treatment that is not clinically indicated. While one NSW decision (Northridge 2000) appears to suggest otherwise, in that case clinicians realised that errors had been made and they themselves provided the treatment that the patient’s family was seeking, making any direction by the court unnecessary.

Advance care planning

The policy response that has the potential to have the greatest impact is the promotion of advance care planning. When a patient lacks the capacity to make treatment decisions for themselves the duty of the substitute decision maker is to make a decision that is in the best interests of that patient. The legislation governing these decisions varies from state to state4 but in most the critical element in determining best interests are the views or wishes of the patient to the extent that they can be ascertained.

Mrs Korp’s circumstances were an example of a dispute about who should be her substitute decision maker and what her wishes were. Like most people she had not written out a statement of her views and wishes concerning treatment. She had not signed an enduring power of attorney for medical treatment: a document called ‘enduring’ because it retains its legal validity beyond the time at which the signor becomes incompetent. It is a document in which a competent person authorises another to make decisions on their behalf should they become incompetent. Even though the law in Australia provides for the making of medical treatment decisions in advance, the prevalence of advance care planning documentation remains very low. The prevalence range has been estimated at 10–20% (Austin Health 2006a) and measured in one study at 11% (Brown et al. 2005).

The establishment and funding of the Respecting Patient Choices (RPC) program was a significant national policy response. Austin Health in Melbourne, with funding from the National Institute of Clinical Studies, piloted the program in 2002 under licence from the Gunderson Lutheran Medical Foundation in Wisconsin US. The direct connection between the issues that have been identified and the program is clear in the following extract from the RPC website (RPC 2007):

Advances in medical technology have given medicine the ability to prolong life through artificial or mechanical means. These advances have created their own dilemmas, especially when the treatments may be of limited or no benefit to the patient. Doctors and family can find themselves having to decide for the patient when to withhold or withdraw life-sustaining treatments when the patient can no longer communicate their own decision. Advance care planning enables a patient’s wishes and views to influence this discussion and decision.

The aims of the program are stated to be to:

- promote an individual’s understanding of their current health and treatment options

- facilitate conversations between the patient and the significant people in their lives about their values, beliefs and goals in life and, in light of their current health status, what medical treatments they would and would not want, in the future

- assist individuals to document their wishes and preferences for future medical treatment, particularly end-of-life treatment, in an advance care plan

- ensure this documentation is transferable so that it goes with the patient to other healthcare services

- ensure that plans are taken into account in a thoughtful and respectful way

- comply with current state legislation (RPC 2007).

- facilitate conversations between the patient and the significant people in their lives about their values, beliefs and goals in life and, in light of their current health status, what medical treatments they would and would not want, in the future

The program involves training consultants who are generally drawn from nursing, social work or other allied health staff to offer a discussion around the first two aims listed above. Where necessary, medical practitioners provide medical advice. The value of an expert discussion was reinforced by research (Brown et al. 2005), which found that providing people with information about advance care planning was, without explanation and assistance, ineffective. The process allows patients to state their wishes about their future healthcare, and express, if relevant, their values and beliefs. They can express their requests about other aspects of end-of-life care such as where they wish to be, what would comfort them and how their spiritual beliefs can be honoured.

Advance care planning is a process which might result in documentation in the form of an enduring power of attorney for medical treatment, a statement of choices and, depending upon the relevant state or territory, any other form of directive that is recognised in that jurisdiction. Critical to the RPC program has been the implementation of practices within the hospital to include any documentation prominently in the clinical file. This is required to ensure that effect is given to the documentation, as a critical measure of success of the program is the extent to which the actual end-of-life care for a person lacking competence reflects that which they had previously asked.

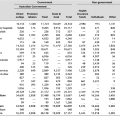

The pilot proved successful and lead to the RPC program being introduced into the major hospitals of three other health services in Melbourne, with funding from the Victorian government. In addition, the Australian government has funded the progressive introduction of the program to one major hospital in each Australian state and territory in 2004–065. Within Victoria, Austin Health, with Australian government funding, has now extended the program to the community in 17 residential aged care facilities and three palliative care services in north-east Melbourne. In addition, a GP information kit has been developed to educate GPs about advance care planning and to assist them to undertake the advance care planning process with patients and residents of aged care facilities.

An evaluation of the community implementation found that 100% of those who completed an advance care plan had their medical treatment wishes respected at their end of life.

- The majority of these residents (88%) died in their facilities receiving palliative care as they had requested. A minority of residents (11%) died in hospital having been transferred there at the resident’s or family’s request for medical treatment or symptom management (Austin Health 2006a p 13).

- The study also found that the length of hospital stay before dying was significantly shorter for those with an Advance Care Plan (6.86 days) compared with those without one (15.27 days).

This evaluation, that of the initial pilot program, and of three of the interstate sites (Austin Health 2006b), have all been very positive. As a consequence, financial support for the program has been substantial. The commitment by the Australian government for 2003–10 is $6.6 million and the Victorian government’s 2006–07 allocation is $1.5 million. A comprehensive evaluation of the wider RPC program is planned to commence in 2007.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS FOR POLICY DEVELOPMENT

The question of withdrawing treatment – particularly food and water – in an end-of-life situation is clearly an emotional one. It raises contentious ethical questions and issues about the application of the law. There is a general reluctance within governments to confront the issues given an unwillingness to deal with the even more contentious issue of euthanasia which inevitably is invoked in the discussions. While decisions about whether treatment is futile or overly burdensome are quite different from acts that constitute euthanasia, there are lobby groups who seek to blur the distinction.

The consequence is that cautious governments seeking to avoid gratuitous controversy will avoid initiating the necessary debate. However, in 2007 Tasmania passed legislation to make it clear that the holder of an enduring power of guardianship does have the power to refuse nutrition and hydration.6 In the same year the government of Western Australia introduced legislation to create the enduring powers of attorney for medical treatment and also to provide for advance directives.7 Even so, the status of advance directives remains limited and uncertainty will continue to surround their application as there may be circumstances ‘in which a health professional or a court will be permitted to disregard an advance directive’ (Willmott et al. 2006 p 211).

Further policy development is also required to eliminate, or at least reduce, uncertainty that can arise with the threshold question of whether or not people can make a decision for themselves. Not only is capacity difficult to quantify but its definition can differ according to the circumstances in which it is being applied. There are variations in who assesses capacity and how it is assessed. Change might follow the policy development work being undertaken by the NSW government. The discussion paper (Attorney General’s Department NSW 2006) is due to lead to a report scheduled for 2007.

The major direction for the future appears to lie with the promotion of advance care planning and, in particular, the expansion and consolidation of the RPC program. Given the potential for controversy in this area the level of financial support from the Australian government could be seen as courageous. The risk exists for claims to be made that the goal is to reduce healthcare costs by encouraging the refusal of treatment and minimising hospital readmissions. To the credit of the Australian government it has never sought an evaluation of the program on the basis of a cost–benefit analysis but has emphasised the importance of promoting individual autonomy and quality of care.

In this respect there appears to be, within the development of policy, a felicitous congruence of goals in that outcomes of the RPC program not only improve healthcare, promote individual autonomy and reduce the emotional cost of end-of-life decision making, but they also reduce demands on the health system. In addition, of course, advance care planning can and does overcome some of the dilemmas that advances in medical science, and in particular PEG feeding, have created for factors in the health system.