CHAPTER 124

Cerebral Palsy

Sathya Vadivelu, DO; Marlís González-Fernández, MD, PhD

Definition

Cerebral palsy (CP) is a neurodevelopmental condition caused by a nonprogressive lesion of the brain. Whereas CP is typically diagnosed early in life and brain lesions are not progressive, it continues to bear effects that may worsen throughout the life span.

Many definitions of CP have been proposed. The most recent was agreed on in 2006 after review of the proposed definition by the International Workshop on Definition and Classification of CP. Through this review, it was decided that CP would be used as a clinically descriptive term instead of an etiologic diagnosis, defined as follows:

Cerebral palsy describes a group of permanent disorders of the development of movement and posture, causing activity limitation, that are attributed to nonprogressive disturbances that occurred in the developing fetal or infant brain. The motor disorders of cerebral palsy are often accompanied by disturbances of sensation, perception, cognition, communication, and behavior, by epilepsy, and by secondary musculoskeletal problems [1].

Prevalence

The prevalence of CP has been reported to range from 1 to 3 per 1000 live births [2–4]. Yeargin-Allsopp and coworkers [3] reported a higher incidence of CP in boys compared with girls, with a ratio of 1.4 to 1. The same study found a higher prevalence of CP in black compared with white children or those of Hispanic descent [3]. Subsequent studies confirmed this finding [5–8]. Maenner and colleagues [8] also evaluated mobility. In this study, the majority of children were ambulatory, followed by those who were nonambulatory or had limited mobility, with the smallest number walking with an assistive device.

Mobility difficulties have been associated with increased mortality of children with CP. In a study by Strauss and coworkers [9], those who were categorized as having poor mobility (defined by the inability to lift the head while in a prone position) had twice the mortality rate as those with high mobility (defined by the ability to roll or to sit). However, the same study found that the overall mortality rate of children with severe disabilities is declining by an estimated 3.4% per year.

Etiology

Risk factors for CP can be divided into pre-pregnancy risk factors, maternal disease, and pregnancy related. Pre-pregnancy risk factors, which have been associated with thrombosis and perinatal stroke, include advanced maternal age and primiparity, respectively. Maternal diseases such as diabetes, anemia, hypertension, epilepsy, thyroid dysfunction, and chronic renal disease have also been associated with CP. Associations have been found with multiple gestation (twins, triplets) and delivery factors such as assisted fertilization, plurality, placental disease, bleeding during pregnancy, preeclampsia or eclampsia, intrauterine exposure to infection (urinary tract infections, sexually transmitted diseases, and rubella, among others) or maternal fever in labor, restricted or excessive growth for gestational age, abnormal presentation at time of delivery, rupture of membranes longer than 24 hours before delivery, and induced labor [10,11]. Apgar score of less than 7 at 5 minutes, low birth weight, and gestational age of less than 37 weeks are also risk factors for CP.

Although many risk factors for CP exist, the actual cause is a cerebral abnormality. CP may be caused by neonatal encephalopathy from hypoxic-ischemic events, ischemic stroke, or congenital malformations [12].

Classification

CP has been classified on the basis of the dominant presentation of tone or movement into spastic, dyskinetic (dystonic or choreoathetotic), and ataxic [1]. It has been further divided on the basis of limb involvement into unilateral (or hemiplegia) or bilateral (either diplegia or quadriplegia) [1,13]. It is also recommended to account for accompanying impairments and anatomic findings in classifying CP [1].

Neuroimaging findings have been associated with specific CP subtypes. Bilateral spastic CP has most frequently been found to have periventricular white matter changes on imaging. On the other hand, unilateral spastic CP has been associated with periventricular white matter lesions, periventricular gliosis, focal cortical dysplasia, and unilateral schizencephaly. Athetoid CP has been associated with cortical or deep gray matter lesions. In ataxic CP, lesion patterns are less common, but imaging may demonstrate cerebellar malformations [14].

Symptoms

Whereas CP has a profound effect on the musculoskeletal system, it can be accompanied by myriad symptoms affecting other body systems. Symptoms vary by disease severity and may include intellectual disability, seizures, learning disorders, skeletal deformities, pain, abnormal tone, weakness, developmental delay, poor dental health, difficulties with bowel and bladder management, difficulties with oral-motor control, tremors, difficulties with sleep, and difficulties with mood. Here we discuss the body systems most commonly affected by CP.

Head, Eyes, Ears, Nose, and Throat

CP may be accompanied by visual deficits, sensorineural hearing loss, poor oral-motor control, and poor dentition. Vision may be hindered by strabismus (esotropia) or nystagmus. Depending on etiology, there may also be concern for retinopathy of prematurity. Difficulty with oral-motor control may lead to excessive drooling, dysphagia, dysarthria, or aphasia [15,16].

Cardiovascular

Cardiovascular disease may be of concern as those with CP age. Increased circulatory system disease in adult CP cases compared with age-matched peers has been reported [17].

Pulmonary

Many CP-associated symptoms can lead to deterioration of the pulmonary system. Dysphagia may lead to aspiration, which in turn can lead to pneumonia. Changes in tone and development of scoliosis can lead to decreased vital capacity and restricted airway disease. As patients age with CP, there may be an increase in respiratory illnesses, including pneumonia, influenza, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [16,17].

Gastrointestinal and Genitourinary

Along with oral-motor impairment, feeding may be affected by swallowing dysfunction. A high incidence of gastroesophageal reflux disease has also been reported [16]. This may be due to associated hiatal hernias, scoliosis, increased intra-abdominal pressure from spasticity, seizures, or neuromuscular incoordination. Regardless of cause, chronic gastroesophageal reflux may lead to esophagitis. This may be manifested with dystonic posturing of the head and neck, hematemesis or vomiting, anemia, or chronic irritability. Chronic peptic esophagitis may potentially cause esophageal mucosal ulceration and stricture formation. Constipation may also arise because of low-fiber or liquid diet, use of medications (including opioids, antispasmodics, antihistamines, and anticonvulsants), immobility, decreased bowel motility, hypotonia, or skeletal abnormalities. Chronic constipation may in turn lead to megarectum, anal fissures, or soiling [16,17].

Musculoskeletal

Musculoskeletal disease is the hallmark of CP. Its impact is lifelong and causes arthritic changes, deformity or contracture, and joint dislocation. This can lead to decreased mobility, osteoporosis, fracture, skin breakdown, and pain [15,17].

Pain is reported in both children and adults with CP and may be caused by muscle imbalance or spasticity. Back pain is commonly reported, followed by pain in weight-bearing joints. The presentation of CP can influence the location of pain. Foot pain is commonly reported in those with diplegic CP, whereas knee pain is more frequent in quadriplegic CP. Neck pain, shoulder pain, and headaches are reported in those with dyskinesia [17]. Pain can affect socialization and education as well as lead to fatigue and decreased mobility [18,19].

Pain affects not only mobility but also strength, endurance, balance, and spasticity. A study looking at aging with CP found that 39% of 20-year-old CP patients could ambulate 20 feet without an assistive device. This declined progressively to 37% by 40 years and 25% by 60 years of age. Subtype also played a role; spastic diplegic patients most commonly showed this progressive decline in mobility [17].

Decreased mobility can lead to osteoporosis. A study in 2008 reported that adults and children with spastic quadriplegia who are nonambulatory have decreased bone density of the lower spine across their life span [17]. Decreased mobility may also influence scoliosis progression over time. It was reported that curves of more than 4 degrees by the age of 15 years led to progressive worsening of spine curvature with age. Curvature of the spine, whether scoliosis, kyphosis, or lordosis, can affect sitting balance, increase pain, and cause difficulties with bowel and bladder management [17].

Sitting may also be influenced by hip subluxation due to muscle imbalance, especially in spastic CP [20]. Hip subluxation can lead to difficulties with wheelchair seating and fit, which may result in skin breakdown and pain, as persistent hip dislocations have been reported to increase pelvic obliquity [20].

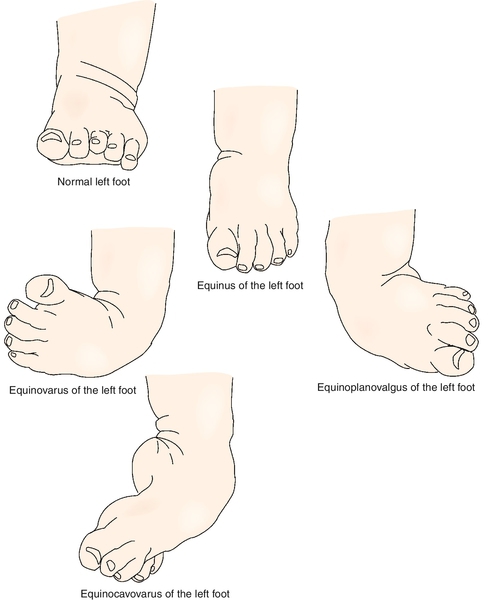

Other joints commonly affected in CP include the knee, foot, and ankle. The most common disorders of the foot are equinus deformity, equinoplanovalgus deformity, and equinocavovarus deformity (Fig. 124.1). Equinus deformity is a disorder of the hindfoot characterized by excessive plantar flexion of the hindfoot in reference to the ankle. It is seen with hypertonicity of the gastrocnemius or soleus muscles. Equinoplanovalgus deformity is seen with pronation of the forefoot and midfoot and is typically accompanied by hallux valgus and valgus deformity at the ankle. This is commonly seen with increased tone to the gastrocnemius and the peroneals. Equinovarus deformity is seen with supination of the midfoot and involves the gastrocnemius and posterior tibialis muscles [21]. Increased tone at the gastrocnemius can also produce toe walking, which is a common occurrence in CP.

Excessive knee flexion due to increased tone in the hamstrings may be seen. However, increased tone alone does not lead to the crouched gait pattern commonly seen in CP. This pattern may be due to a combination of skeletal deformity, weakness, spasticity, and poor motor control [22,23]. It is characterized by flexion at the hips, due in part to increased tone of the iliopsoas, and flexion at the knees. Increased tone of the hip adductors may lead to further gait abnormality, producing a scissoring gait pattern.

Neurologic

Neurologic symptoms are manifested across a range of body systems. This may include impairments of oral-motor control, vision deficits, and sensorineural hearing loss [15,16]. Patients may have seizures, cognitive problems, sensory impairments, weakness, movement disorders, abnormal motor control, and muscle hypertonicity.

Seizures are most commonly seen in those with spastic quadriplegia. Their presentation can vary from generalized tonic-clonic to focal, complex partial, simple partial, myoclonic, typical absence, atypical absence, or atonic. Seizures may progress to epilepsy. A study by Humphreys and coworkers [24] found an association between the development of epilepsy and the presence of neonatal seizures in CP patients with periventricular leukomalacia.

Sensory impairments can also be seen in patients with CP. Difficulties with proprioception, two-point discrimination, and stereognosis may be present. This is most common in those with the spastic hemiplegic subtype [25]. Recent literature supports these findings and notes a correlation between sensory impairment and involvement of the thalamocortical pathways [26,27].

The predominant neurologic findings in those with CP are changes in tone or movement. This is evident by the way in which CP is classified: spastic, dyskinetic (dystonic or choreoathetotic), or ataxic [1]. Spastic CP is the most common, and spasticity is its predominant feature. Spasticity is defined as hypertonia that produces increased resistance in response to increased speed of stretch. The dystonic pattern seen in dyskinetic CP is characterized by involuntary muscle contractions that can be sustained or intermittent, leading to twisting or repetitive movements or abnormal postures [28]. The choreoathetotic pattern is characterized by the combination of athetoid (slow, writhing) and choreiform (abrupt, jerky) movements. The ataxic subtype is characterized by uncoordinated movements. Hypotonia may be seen early in infancy, although it may still be present intermittently with dyskinetic CP.

Other

Sleep may be affected in those with CP as a result of sleep anxiety, night wakings, parasomnias, sleep disordered breathing, intellectual impairment leading to difficulty in self-soothing to sleep, altered light perception, reduced melatonin secretion, epilepsy, or pain. Pain may be due to restricted movement, contracture, or spasms. Wayte and coworkers [29] reported that persons with CP needed parental support at night most commonly for restless sleep and turning over in bed. This need for parental support led to increased caregiver burden and depression [30].

Depression has also been reported in patients with CP. It was found that adults older than 40 years with CP experienced greater levels of loneliness and depression than did 60-year-olds without a disability [17]. Depression has been associated with concern about lack of resources and expertise in care for adults with CP [31].

Physical Examination

As CP may bear influence on all body systems, it is necessary to obtain a complete history and to perform a thorough examination. It is important to consider the age of the patient and to modify the examination accordingly. Assessment should include an evaluation of function, a detailed musculoskeletal examination (to evaluate joint range of motion, deformity, or malalignment), and a thorough neurologic examination (including evaluation of strength, tone, and sensation). Psychological and cognitive assessment may also be performed.

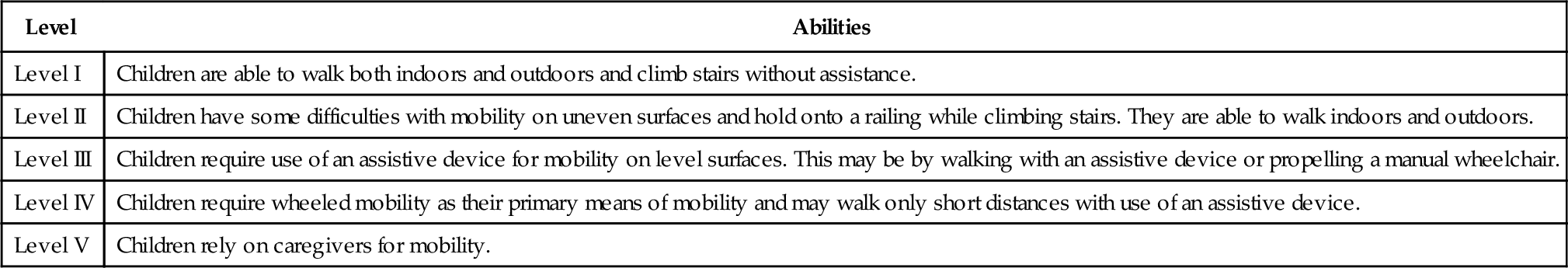

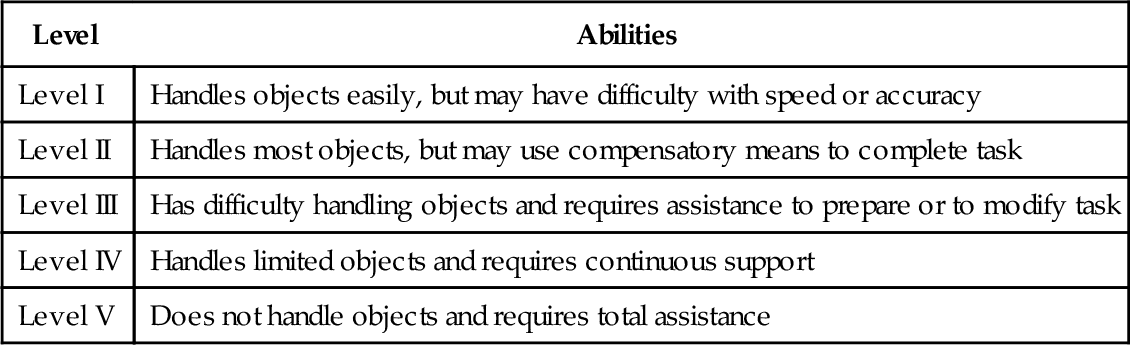

Mobility is classified by the Gross Motor Functional Classification System, which is divided into five categories based on independence with mobility and use of assistive devices (Table 124.1) [1,13,32–34]. Upper extremity function is categorized by the Manual Ability Classification System. This system accounts for age and primarily assesses how patients handle objects in daily life. The classification system was originally designed for those between 8 and 12 years old. It is divided into five levels with progressive involvement from level I to level V (Table 124.2). In a study by Eliasson and colleagues [35], children with hemiplegia were primarily level II, those with diplegia were either level I or level IV, and those with quadriplegia were level IV or level V.

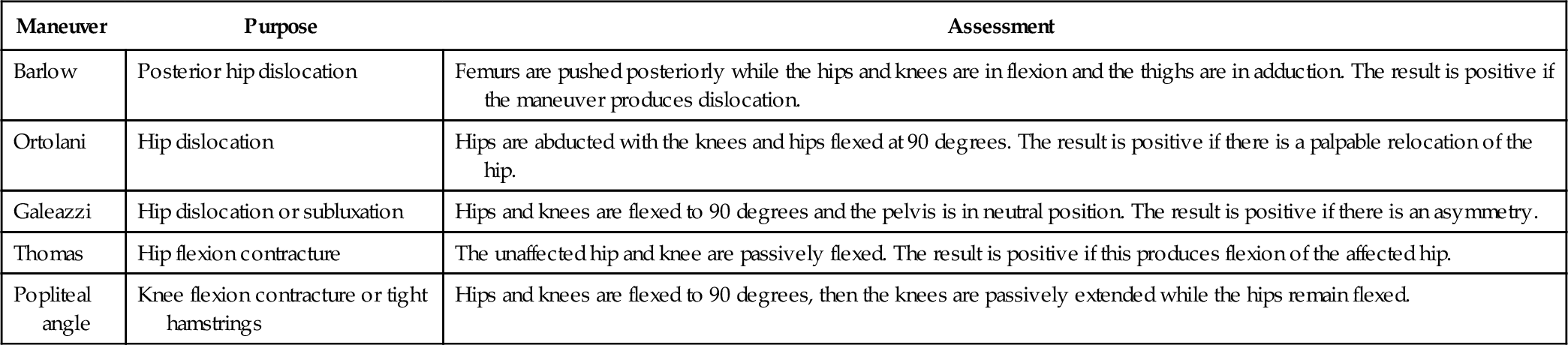

Musculoskeletal abnormalities should be carefully evaluated as they have great impact on overall function. Signs of scoliosis should be observed. Passive and active range of motion should be assessed at all joints and may be measured with a goniometer. Specific tests can be used for the evaluation of common abnormalities (Table 124.3). Examination of the hips in infants should include assessment of hip dislocation with the Barlow and Ortolani tests. The Galeazzi or Allis sign may indicate hip dislocation or subluxation. It will be seen as an asymmetry when hips and knees are flexed to 90 degrees and the pelvis is in neutral position. It is important to assess hip abduction because increased tone to the hip adductors or hip deformity can lead to difficulties with perineal care. This is tested in the supine position, with knees flexed and hips flexed to 90 degrees, after which the hips are abducted. Internal and external rotation of the hips should be assessed. The Thomas test may be used evaluate for hip flexion contracture [36,37]. Popliteal angles should be measured with hips flexed to 90 degrees and knees initially in a flexed position, then passively extended. Ankle dorsiflexion should be measured with the knee flexed to assess tightness of the soleus and the knee extended to assess gastrocnemius tightness [37]. Deformity of the foot and ankle should also be documented. Analysis of gait in a formal gait laboratory may be useful in assessing the musculoskeletal system and mobility [34].

Neurologic examination should be appropriate for the patient’s age. Primitive infantile reflexes, such as the Moro, palmar grasp, asymmetric tonic neck, plantar grasp, and Galant, should be provoked. The asymmetric tonic neck reflex should subside by 3 months. It is elicited by rotation of the patient’s head, causing extension of extremities on the chin side and flexion on the occiput side. The Galant reflex is seen with curvature of the trunk toward the side of stimulation when the examiner scratches the skin of the patient down the back. This response should be extinguished by 4 months. The palmar grasp response, which is seen with finger flexion of the patient when the examiner’s finger is placed in the palm, should disappear by 6 months. The Moro reflex, which is caused by sudden head extension and leads to upper extremity abduction, then adduction and flexion, should resolve by 6 months. The plantar grasp response is seen with flexion of the toes when the sole of the foot is touched. This should be extinguished by 15 months [38].

Muscle strength may be evaluated by observation or through formal manual muscle testing, depending on the patient’s age. Developmental milestones should be discussed with parents or observed. Emergence of hand dominance at an early age should be discussed with parents as this may indicate weakness or difficulties with the nondominant hand. Variations in tone should be assessed. Spasticity may be classified by the Ashworth scale, the modified Ashworth scale, or the Tardieu rating scale. The Ashworth scale rates spasticity from 1 to 5 with increasing severity, and the modified Ashworth scale rates spasticity from 0 to 4 with increasing severity; the Tardieu rating scale measures spasticity at varying velocities [39]. Sensory examination may also be performed with assessment of proprioception, two-point discrimination, and stereognosis [25–27].

Muscle stretch reflexes should be obtained and may be increased. Formal vision and hearing assessment to ascertain visual impairment or hearing loss is often necessary. Mood should be discussed because depression is seen in those aging with CP [31]. Neuropsychological examination may be beneficial in assessment of cognitive concerns.

Functional Limitations

Functional limitations vary by subtype and comorbidities, many of which are described earlier and involve activities of daily living and mobility. It is reported that gross motor function may improve up to the age of 7 years, but musculoskeletal disease may worsen, potentially affecting mobility in children with CP [34]. Research by Palmer [40] suggests that the best predictor of functional limitation is the rate of motor development. This can be evaluated by use of the developmental quotient (chronologic age divided by developmental age) or through videotape assessment of spontaneous general movements during the first months of life [40].

Engel-Yeger and colleagues [41] reported that people with CP, compared with their typically developing peers, were more limited in their activities, were limited in the frequency of activity participation outside of school, and did not as frequently interact with peers during activities. This same article suggested that it may be the physical limitations that account for these differences.

Diagnostic Studies

Head, Eyes, Ears, Nose, and Throat

Audiometry may be obtained to assess hearing. Neuro-ophthalmology referral may be necessary for visual assessment.

Cardiovascular

With aging (if cardiac concerns arise), electrocardiography, thallium or exercise-induced stress testing, or echocardiography may be warranted.

Pulmonary

Chest radiographs may be obtained if pneumonia is suspected or there is a change in respiratory status.

Pulmonary function tests may be performed if there is concern for development of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Gastrointestinal and Genitourinary

Abdominal plain films should be obtained if chronic constipation develops. Gastroenterology consultation and upper endoscopy may be necessary if there is concern for peptic esophagitis or hematemesis. If dysphagia is suspected, formal evaluation by a speech-language pathologist is warranted. This evaluation may include instrumental examination (modified barium swallow study or fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing).

Musculoskeletal

Scoliosis films should be obtained to measure and to evaluate scoliotic curves. Hip radiographs should be ordered when concern for congenital dysplasia or dislocation exists. Radiographs may be obtained for any suspected fracture of the limbs or vertebral compression fracture. Radiographs may also be useful in assessing degenerative changes of the peripheral joints or spine. To assess bone density, a bone density study (DEXA scan) may be ordered.

Neurologic

Initial evaluation of suspected intracranial disease in infancy may begin with cranial ultrasonography [40]. This technique is useful before cranial suture and fontanelle closure and may reveal hemorrhage, ventricular enlargement, or cystic changes. In children and adults, computed tomography may assess for hemorrhagic changes, but its use should be carefully considered, given the amount of radiation exposure. Magnetic resonance imaging is used to assess the underlying pathologic brain changes associated with the development of CP. Common findings may include hypoxic-ischemic injuries, periventricular leukomalacia, schizencephaly, and cerebellar malformations. Krageloh-Mann and Horber [42] reported that 86% of magnetic resonance images obtained in children with CP were abnormal and 83% of those gave insight into the etiology of the child’s CP. There is also evidence to suggest that diffusion magnetic resonance imaging to evaluate white matter lesions, specifically looking at the corticomotor and sensorimotor tracts, is useful [26,27].

Treatment

Treatment of CP should focus on management of symptoms, maximization of function, and prevention of complications. Currently there is no cure for CP.

Initial

When treatment of CP is initiated, existing symptoms and comorbidities as well as potential complications should be considered. One such symptom may be pain, which should be addressed on the basis of etiology. If pain is due to degenerative changes, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories may be used. Pain may arise from a trigger point and may be treated with trigger point injection. Complications from immobility, such as skin breakdown, may arise. These can be treated by off-loading of pressure but may require further interventions, such as débridement or surgical closure. Immobility can lead to pain and fatigue, for which physical or occupational therapy can be implemented. Immobility may also lead to constipation, which may require dietary modifications (increasing fiber intake), stool softeners, enemas, or other laxatives [16]. Discomfort may also arise from gastroesophageal reflux disease, for which proton pump inhibitors have been shown to be effective [16]. Depression may also arise, which may be treated pharmacologically. Referral to a psychologist or psychiatrist may also be necessary.

Rehabilitation

In establishing a treatment program, it is important to take a multidisciplinary approach with focused and clear goals in mind. Physical therapists, occupational therapists, speech-language pathologists, and neuropsychologists may all be involved to varying degrees and at varying frequencies. Patients’ goals will vary significantly and may range from independence in basic activities of daily living to assistance with management of tone, prevention of contracture, and maximizing independence with vocational or sports interests.

A wide range of interventions are available for management of abnormal tone. Assessment must be made as to whether a focal or generalized intervention is required. Physical therapy or occupational therapy may be started in either scenario to work toward implementing a home stretching program and providing education to the patient and the family on the importance of stretching. This is especially important during growth. A wide variety of orthotics may be used as well to help preserve range of motion and for functional tasks, such as providing support at the foot and ankle with mobility or support at the wrist while performing manual activities. Constraint-induced movement therapy may also be considered to promote functional use of the affected limb in those with unilateral involvement.

Generalized interventions for management of spasticity may include oral medications or intrathecal medications. Oral medications include baclofen, dantrolene, clonidine, tizanidine, and benzodiazepines. Most oral medications can have systemic effects that can affect cognition or lead to sedation. Intrathecal delivery of medication is known to have fewer systemic effects. Baclofen may be delivered through an intrathecal pump to manage spasticity [34].

Procedures

If focal intervention is needed, patients may benefit from localized procedures such as botulinum toxin or phenol injections. Botulinum toxin has been shown to be effective in reducing spasticity short term. Long-term efficacy of botulinum toxin is still unclear [34]. Botulinum toxin may be used in combination with serial casting; however, there is mixed evidence about the efficacy of this combined intervention [34].

Surgery

Surgery is an option for both focal and generalized interventions. Selective dorsal rhizotomy may be considered as a surgical treatment to help manage focal spasticity. Orthopedic surgeries to correct contracture or deformity may be necessary as well. This may include tendon lengthening (typically of the Achilles or adductors) and bone correction (such as derotational osteotomies). Generalized interventions for surgical management of spasticity may include placement of an intrathecal pump for delivery of intrathecal medications. Intrathecal delivery of medication is known to have fewer systemic effects. Baclofen may be delivered through an intrathecal pump to manage spasticity [34].

Potential Disease Complications

Because CP is a lifelong disorder, complications associated with aging are often seen. These complications may affect all body systems but predominantly include changes in tone, development of contracture, pain, weakness, decreased mobility, and depression. As described in previous sections of this chapter, there may be increased risk of circulatory system disease, respiratory illnesses, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease, constipation, osteoporosis, and seizures. Early-onset arthritis may also be of concern [15].

Potential Treatment Complications

Complications associated with the treatment of CP vary on the basis of the intervention. All medications have potential side effects. Oral medications, such as baclofen, dantrolene, tizanidine, and benzodiazepines, may cause varying degrees of weakness and sedation. Baclofen and benzodiazepines may lead to cognitive changes. Use of clonidine may lead to hypotension and bradycardia. Intrathecal administration of baclofen has fewer systemic effects, but other potential risks are associated with the pump and catheter. Programming errors, kinked or broken catheter, or pump malfunctioning can lead to baclofen overdose (sedation, lethargy, respiratory failure, and urinary retention) or baclofen withdrawal (cognitive changes, increased spasticity, pruritus, and seizures). Use of focal injections to treat spasticity may lead to infection at the injection site, soreness, or bleeding. Phenol may lead to dysesthesias when it is injected at the site of a mixed sensory-motor nerve. Botulinum toxin may cause weakness and in rare cases botulism-like symptoms, including difficulty in breathing and dysphagia.

Serial casting may lead to skin irritation and potential skin breakdown. Range of motion and stretching can cause pain and have the potential to cause fracture if stretching is performed too aggressively in an osteoporotic patient. Surgery, including dorsal rhizotomy and orthopedic surgeries, may have complications of postoperative pain and constipation in addition to risks of the actual procedure. There are also increased risks associated with anesthesia use when respiratory muscle compromise is present.