CHAPTER 122

Cardiac Rehabilitation

Definition

Cardiac rehabilitation is the integrated treatment of individuals after cardiac events or procedures with the goals of maximizing physical function, promoting emotional adjustment, modifying cardiac risk factors, and addressing return to previous social roles and responsibilities. The American Heart Association 2012 update estimates cardiovascular disease prevalence to be 86,200,000 people in the United States; coronary heart disease affects 16,300,000. Of those with coronary heart disease, 7,900,000 have had myocardial infarction, 9,000,000 have angina pectoris, 5,700,000 have heart failure, and 650,000 to 1,300,000 have congenital cardiovascular defects.

Cardiovascular diseases have continued to be the leading cause of mortality in both men and women for more than a century and accounted for 32.8% of all deaths in 2008 [1]. Cardiac rehabilitation supports those who survive to change their lifestyle, to maximize their functional capacity and quality of life, and to decrease their risk for future cardiac events. Cardiac rehabilitation may benefit individuals after acute coronary syndrome, cardiac surgery (coronary artery bypass graft, valve replacement, transplantation, ventricular reduction surgery, correction of congenital heart defect), and compensated congestive heart failure. Cardiac rehabilitation comprehensively addresses risk factor modification and secondary prevention through exercise training, smoking cessation, diet modification, evaluation and treatment of psychosocial stressors, education about the disease process, return to work, and maximizing the medical treatment of comorbidities (such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and obesity). In a meta-analysis of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation programs, cardiovascular mortality was decreased 26%, overall mortality was decreased 13%, and hospital readmissions were reduced 31% compared with usual care in patients with myocardial infarction, percutaneous interventions, coronary artery bypass graft, or known cardiac disease [2].

Symptoms

The individual with a recent cardiac event or procedure frequently complains of decreased endurance for walking or climbing stairs, increased dyspnea during physical activity, and fatigue. If arrhythmia is present, the patient may feel palpitations. Chest pain may accompany physical exertion or emotional stress. Pain due to surgical incisions of the extremities or chest wall may also be present. Symptoms of heart failure, such as orthopnea and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, may also be present. The person may feel anxious about any type of physical exercise, resumption of sexual activities, and return to work. In many cases, the patient may have symptoms suggesting depression, such as emotional lability, listlessness, poor sleep with frequent or early morning awakenings, and lack of interest in previously enjoyed activities.

Physical Examination

Observation of the patient should look for signs of depression and anxiety. During the examination of the cardiac patient, the clinician will search for signs of complications after the cardiac event or cardiac procedure. Findings of congestive heart failure or fluid overload, such as dyspnea at rest, rales, decreased basilar lung sounds, pleural or pericardial rub, dependent edema, elevated jugular venous distention, or S3 gallop, should be evaluated. Palpation of decreased or absent pulses in the extremities may suggest the common comorbidity of peripheral vascular disease. Wounds such as sternotomies, vascular harvest sites, chest tube insertion sites, pacemaker insertion sites, and arterial puncture sites should be carefully examined for appropriate healing or signs of infection before exercise programs are prescribed. Manual muscle testing of the extremities provides an indication of the degree of skeletal muscle atrophy due to decreased physical activity. Observation of the patient should look for signs of undue dyspnea during standing and ambulation. The patient should be able to comfortably walk at a slow cadence unless there is marked congestive heart failure or lung disease.

Functional Limitations

Functional limitations due to cardiac disease alone are related to the workload the myocardium can sustain before signs of cardiac dysfunction result. Overall endurance is decreased. The degree and severity of cardiac impairment may limit a patient’s physical progress and ultimate maximum level of function. The patient may later return to physically demanding activity, such as heavy labor or competitive tennis (both 8 metabolic equivalents or METs), after rehabilitation that follows uncomplicated coronary angioplasty or stenting without myocardial infarction. However, for the patient who experienced myocardial infarction complicated by congestive heart failure and arrhythmia, the 3 to 5 METs required for walking to a neighbor’s home or performing the household chores may be limited by dyspnea. Further compromise of progress is related to the common comorbidities of obesity, cerebrovascular disease, intrinsic lung disease, diabetes mellitus, and peripheral vascular disease. Impairment due to neurologic, rheumatologic, or orthopedic disease may require specific adaptations to allow conditioning and strengthening exercise.

Most patients with uncomplicated cardiac disease are able to ambulate and perform their self-care on discharge from the hospital. A slow stroll and being able to perform basic activities of daily living are not adequate for most individuals and do not predict excellent quality of life for the individual not referred to rehabilitation. Cardiac rehabilitation maximizes the person’s functional restoration, allowing return to work, social roles, and recreational activity. Despite the known benefits of cardiac rehabilitation, the majority of eligible individuals are not enrolled [3].

Emotional stress and an individual’s response to it may also produce functional limitations when return to social roles and responsibilities is considered. This may range from anxiety about physical exertion to major reactive depression. Dysfunction such as ischemia, arrhythmia, or even sudden death may be produced by emotional demands such as anxiety [4–6]. This is likely to be due to increased sympathetic drive in the autonomic nervous system, which predisposes the individual to more endothelial damage and cardiac arrhythmias mediated by catecholamines. Depression accounts for approximately the same (35%) risk for myocardial infarction as smoking does [7]. This argues strongly for a clear psychological screening of patients with cardiac events. Patients whose depression was diagnosed and treated by selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) at the time of their initial myocardial infarction had 43% less new myocardial infarction and cardiac death compared with treatment with non-SSRIs [8]. This is due to an antiplatelet aggregation effect unrelated to aspirin or clopidogrel bisulfate (Plavix).

Diagnostic Studies

The clinician should evaluate the patient’s lipid profile to guide pharmacologic and dietary management of hyperlipidemia and hypercholesterolemia. Tight diabetes control may decrease the rate of atheroma formation, and glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) level is used to ascertain the recent success of blood glucose control [9]. Calculation of body mass index assists in targeting ideal body weight.

For the individual with dyspnea on exertion and the comorbidity of lung disease, pulmonary function testing will clarify the contribution of obstructive or restrictive lung disease to the symptoms. Treatable conditions, such as reactive airways and hypoxia during exercise, should be addressed before beginning of cardiac rehabilitation for maximal benefit. Combined ventilatory gas analysis by use of a metabolic cart and electrocardiographic monitoring may differentiate cardiac versus pulmonary exercise-induced dyspnea, chest pain, or fatigue. This may be especially useful in patients with congestive heart failure [10].

A symptom-limited functional exercise test with a metabolic cart is administered 2 to 6 weeks after adequate time for healing and provides the best guide to exercise prescription. The specific timing of exercise testing depends on the amount of myocardium damage, the amount of time needed for healing of surgical sites, the need for return to work, and the practice pattern of the clinician administering the test. As opposed to commonly performed diagnostic exercise test protocols, such as the Bruce protocol, that seek to elicit cardiac symptoms, functional exercise testing documents work capacity and cardiopulmonary function. Functional exercise testing protocols start at a lower exercise intensity level than common diagnostic protocols do and increase fewer METs per stage. Treadmill testing following a ramp, modified Naughton, or Naughton-Balke protocol is especially well suited to guide cardiac rehabilitation exercise training because these protocols use smaller increments of intensity that more accurately portray functional capacity. Alternatively, bicycle ergometer protocols may also use smaller gradations of exercise intensity. Bicycle ergometry protocols should be considered for individuals with balance deficits, mild neurologic impairment, or orthopedic limitations.

Echocardiographic, pharmacologic, or nuclear medicine exercise stress testing should be considered for patients with marked lower extremity limitations, severe debility, or electrocardiograms that are difficult to interpret. Most patients have had many electrocardiograms during their hospital stay or evaluation. In the outpatient setting, electrocardiograms should be ordered if there is a change in clinical status, such as new symptoms (e.g., the resumption of angina). For the most part, patients are also monitored by telemetry during at least the initial part of their cardiac rehabilitation.

Patients should be screened for psychosocial stressors, such as anxiety and depression. Besides asking the patient about the symptoms of anxiety, anger, persistent sadness, excessive fatigue, and abnormal sleep architecture, commonly used questionnaires that are easy to administer in an office setting are the Beck Depression Inventory and the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Both take only a few minutes to complete and can be used to monitor the effectiveness of treatment.

Treatment

Initial

Cardiac rehabilitation begins with risk factor reduction. Fully integrated cardiac rehabilitation programs enroll the individual into exercise training, dietary interventions, and psychosocial interventions. The referring physician then becomes the supporter of the patient, shifting the patient’s lifestyle to making responsible health choices. Consider a discussion of the cardiac rehabilitation experience. The initial medical management focuses on optimizing the cardiac medication regimen to control or to prevent hypertension, ischemia, arrhythmia, hyperlipidemia, fluid overload, or other complications that follow the patient’s cardiac event. Diabetes management is also critical to secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Concurrent with medical management, the clinician prescribing cardiac rehabilitation must promote choices for healthy living. Each cardiac patient has choices about smoking, diet, exercise, and stress management. Smoking cessation has the highest rates of success by combining participation in a smoking cessation support group with pharmacologic management of the craving due to nicotine addiction. Bupropion combined with a nicotine patch, gum, or lozenges works well. Have the patient begin taking the bupropion hydrochloride (150 mg every day for the first 3 days, then 150 mg twice daily) 1 to 2 weeks before the chosen date to quit smoking and begin using the nicotine supplement at the time of smoking cessation. This should coincide with the first smoking cessation support group meeting.

Dietary modification has been documented to improve the lipid profile [11]. Ask the patient to keep a food diary for at least 3 days to bring to the cardiac rehabilitation program or refer the patient to a registered dietitian for evaluation and education on appropriate heart healthy dietary choices. The American Heart Association revised cardiac diet recommendations of 2006 are substantially more stringent on the saturated fat intake (Table 122.1) [11]. The dietitian may recommend the American Heart Association diet, but other choices could be the Mediterranean diet or the lacto-ovovegetarian diet. None of these three diets has been shown to be superior, and the choice of diet is based primarily on the patient’s ability to follow the diet.

The individual with cardiac disease often needs to learn strategies to decrease the emotional stress of anxiety and depression. Patients with either of these based on the original screening should be treated. SSRIs treat both components fairly well with few side effects. A referral for counseling with a mental health professional can provide patients with an assortment of tools to learn relaxation and provides a forum for the discussion of emotional symptoms surrounding cardiac events in their life. Women have a higher rate of anxiety and psychosomatic complaints than do men beginning cardiac rehabilitation and can benefit from greater attention to psychosocial interventions [12,13]. In the busy clinic, the clinician can teach the individual a simple stress reduction technique. A relaxation response documented by augmented parasympathetic activity has been noted during the simple exercise of paced breathing. Ask the patient to pace his or her breathing, using a clock, for 5 to 10 minutes twice daily. The patient should time inhalation and exhalation equally for 3 to 5 seconds each while avoiding air hunger or hyperventilation. Once he or she performs this exercise with facility, additional relaxation can be achieved from further slowing of the breathing rate or prolonging the period of exhalation [14].

Return to sexual activity should be frankly discussed with patients and their sexual partners to decrease their anxiety about sexual activity after a cardiac event [15]. Sexual activity between couples with a long-standing relationship requires 3 to 5 METs. Extramarital sex causes higher energy demands. In a statement from the American Heart Association, sexual activity is safe to be resumed, although erectile dysfunction medications should be avoided in patients using nitrates for angina due to coronary artery disease [16].

Return to work and recreational activities should be based on patients’ clinical status and their previous work. In a meta-analysis of European cohort studies, significant job-related emotional stress also increased the risk for cardiac events [17]. The exercise test performance predicts the level of vocational work capacity. If the patient’s work capacity is only 3 to 4 METs or less, return to work may be unrealistic. Even self-care activities are likely to produce symptoms at this low level. With a capacity of 5 to 7 METs, the person should be able to perform sedentary work and most domestic roles. If the person can exercise beyond 7 METs, most types of work can be performed without restriction, except those involving heavy physical labor. For recreational activity, the MET level required should be evaluated before return to play is recommended. The Compendium of Physical Activities can be used to guide return to work and recreation activities and can also be accessed online (https://sites.google.com/site/compendiumofphysicalactivities/) [18]. The following are some common recreational activities and their MET requirements: walking at a moderate pace, 3.5; tennis, 4.5 to 8; golf, 4 to 5; downhill skiing, 4 to 8; bowling, 3 to 5; and volleyball, 3 to 4.

Rehabilitation

Cardiac rehabilitation begins in the hospital with early mobilization, dietary instruction, and medication and disease process education. Many patients have relatively minimally invasive procedures without the loss of heart muscle function, such as coronary stent placement during acute angina. The following recommendations assume some kind of cardiac debility.

Consider a short stay in acute inpatient rehabilitation if the person is stable but unable to perform basic mobility and self-care tasks at a household level. Recommend a self-directed walking program if the patient is unable to begin a supervised exercise training program on discharge from the hospital. This should be reserved for individuals with an uncomplicated hospital course and for whom exercise is not contraindicated (Table 122.2). The patient should walk primarily on level surfaces at a slower pace with the goal of 10 to 30 minutes of walking at least three to five times per week at an intensity that will allow talking. Ask patients to keep a walking journal and review it with them.

If no significant cardiac damage has occurred, such as after angioplasty, the period of convalescence may be shortened on the basis of the clinician’s judgment and considerations such as the individual’s need to return to previous pursuits.

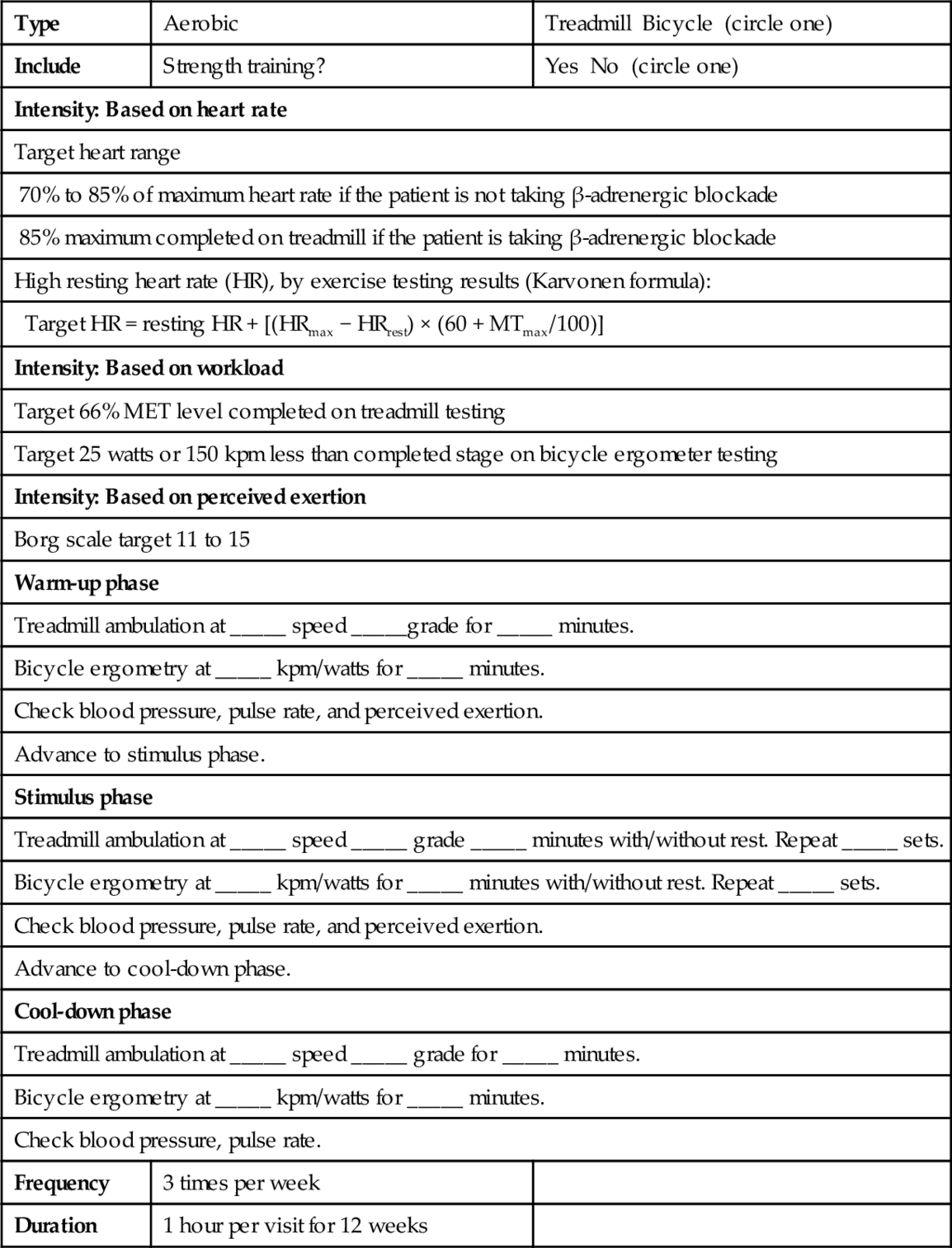

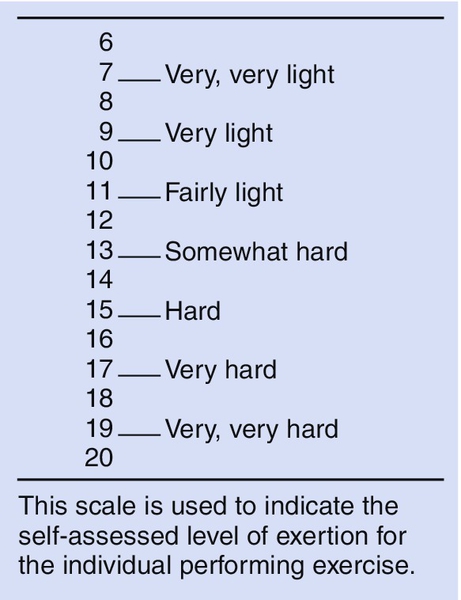

Physical training with referral to cardiac rehabilitation begins at the end of the convalescence period. Ideally, this is based on functional exercise testing described in the preceding section on diagnostic studies. Arguments have been made that exercise testing at this stage does not improve the outcome or safety of a supervised cardiac rehabilitation therapy program, but functional exercise testing is still the “gold standard.” [19] Exercise prescription includes type, target intensity, frequency, and duration of exercise. Aerobic exercises, such as walking and bicycling, are the mainstay of most programs. Prescribe aerobic exercise intensity on the basis of heart rate, exercise intensity (METs), or perceived exertion (Table 122.3). The visual analog Borg scale rates perceived exertion (Fig. 122.1) and has been shown to correlate linearly with heart rate and oxygen consumption [20]. For the patient taking beta blockers, perceived exertion is a good guideline as the heart rate response is somewhat blunted. The frequency of exercise sessions is usually three to five times per week.

Aerobic exercise sessions begin with a warm-up phase of 2 to 5 minutes at a lower intensity of exercise to limber the joints, to open collateral circulation, and to decrease peripheral vascular resistance. The stimulus or conditioning phase may be continuous or discontinuous, with the 3- to 12-month goal of at least 20 to 30 minutes of aerobic exercise. This may be broken down as a discontinuous exercise with rest breaks between periods of conditioning exercise. A cool-down phase at a lower intensity of exercise will prevent hypotension and, later, joint pain. Duration of aerobic exercise sessions depends on the individual’s level of fitness. For the markedly debilitated patient, 3 to 5 minutes in the target range will provide benefit initially. The deconditioned individual should be progressed during 4 to 12 weeks to this 20- to 30-minute stimulus phase. Electrocardiographic monitoring during aerobic exercise is recommended for patients with low ejection fraction, abnormal blood pressure response to exercise, ST-segment depression during low-level exercise testing, or serious ventricular arrhythmia [21].

Strength training or circuit training with resistance exercises adds skeletal muscle strength and facilitates building of local muscle endurance for those with good left ventricular function. This should especially be considered for the cardiac patient who may be returning to a physically demanding job. Patients who use free weights should begin with the lowest weight that produces a perceived exertion of 11 to 13 after 10 to 15 repetitions (see Fig. 122.1). One to three sets will build strength. This should involve enough different exercises to include all major muscle groups of the upper and lower extremities.

The clinic-based supervised exercise program typically lasts 1 to 3 months, with the exercise prescription upgraded monthly. Monthly reevaluation should include consideration of increasing the stimulus-phase intensity or duration of aerobic exercise. After 2 to 3 months of a conditioning exercise program, the individual should have the ability to achieve 7 to 8 METs of sustained exercise. Once the patient has achieved this goal, repeat of the exercise test will show the level of improvement and guide the transition to a self-directed maintenance program. The patient may choose to follow his or her target heart rate or exertion level during exercise.

The benefits of exercise training include increased maximum oxygen uptake, increased endurance for activities of daily living, increased functional capacity, decreased heart rate during exercise, decreased rate-pressure product, decreased fatigue, decreased dyspnea, and decreased symptoms of heart failure. Exercise training reduces atherogenic and thrombotic risk factors by managing or preventing excess body weight, increasing high-density lipoprotein cholesterol concentration, decreasing plasma triglyceride levels, decreasing platelet aggregation, and improving glucose levels. Myocardial perfusion may be improved by increased coronary blood flow. The progress of coronary atherosclerosis may be slowed or possibly reversed.

Home-based cardiac rehabilitation programs should be considered for less medically complex patients unable to attend outpatient programs. A review comparing home-based versus center-based rehabilitation for low-risk cardiac patients after uncomplicated myocardial infarction or coronary artery bypass graft showed no difference in morbidity and mortality, health-related quality of life, or modifiable risk factor reduction [22].

Psychosocial interventions provide specific tools to live with emotional stress, depression, anxiety, and returning to work. Adjunct treatment with medication may be necessary if counseling and lifestyle management are inadequate alone.

Procedures

Medically stabilized cardiac patients need few procedures. Large pulmonary effusions may decrease exercise capacity, requiring the need for thoracentesis. Interventional cardiology procedures may be needed for acutely occluded stents, angioplasty, or grafts. For the patient with significant arrhythmias, pacemaker or defibrillator placement or adjustment may be necessary. The patient with worsening cardiac symptoms may need to repeat coronary angiography or other diagnostic testing if medication adjustment is unsuccessful.

Surgery

Surgical interventions may be needed for failed coronary bypass vascular grafts, infected wounds, or pseudoaneurysms at arterial puncture sites. Permanent pacemaker or implantable defibrillators may be necessary for individuals with arrhythmias not controlled with medications.

Potential Disease Complications

The most common cause of mortality in the United States is cardiac disease. Decreased exercise tolerance and decreased work capacity are the most common functional impairments. Medical complications include congestive heart failure, arrhythmia, repeated infarction, and possible closure of coronary artery grafts and stents or angioplasties. Sternotomies may not heal or become infected, requiring surgical débridement or revision. Because coronary artery disease is associated with generalized atherosclerotic vascular disease, one should be aware of possible stroke, peripheral vascular insufficiency, and other end-organ manifestations of compromised vascular supply. Even with referral to cardiac rehabilitation, individuals may still experience loss of social roles, vocational barriers, and difficulty with emotional adjustment despite excellent physical improvement and appropriate psychosocial interventions.

Potential Treatment Complications

There is a slight risk of precipitation of a cardiac event during cardiac rehabilitation. In one study, the risk of a significant cardiac event during exercise training, such as new infarct or death, occurred at a rate of 1/50,000 to 1/120,000 person-hours of exercise [23]. Preventing the enrollment into cardiac rehabilitation of patients who are not medically stabilized can minimize the risk. Exercise testing has relative and absolute contraindications that should be followed. These contraindications have been elucidated in great detail elsewhere [10]. In general, however, do not test patients with unstable angina, malignant cardiac arrhythmia, pericarditis, endocarditis, severe left ventricular dysfunction, severe aortic stenosis, or any other acute noncardiac disease. Common adverse treatment events are postexercise hypotension or arrhythmia and muscle or joint pain. These are minimized if exercise testing guides the cardiac rehabilitation prescription.