CHAPTER 120

Ankylosing Spondylitis

George W. Deimel, IV, MD; Steven E. Braverman, MD

Definition

Ankylosing spondylitis is a chronic, inflammatory, rheumatologic disorder that primarily affects the spinal column and sacroiliac joints. It is classified as a seronegative spondyloarthropathy. Enthesitis (inflammation of the soft tissues attaching tendons, ligaments, and joint capsules to bone), synovitis, and inflammation of the synovial capsule are characteristic of its involvement. The most common sites include sacroiliac, apophyseal, and discovertebral joints of the spine; costochondral and manubriosternal joints; paravertebral ligaments; and attachments of the Achilles tendon and plantar fascia. Peripheral joint involvement is less common but occurs in the more severe forms of the disease or with younger age at onset [1].

The onset of symptoms is usually in late adolescence or early adulthood, and there is a 3:1 male predilection. It is not associated with the presence of rheumatoid factor or antinuclear antibodies. Although there is a genetic association with the HLA-B27 histocompatibility antigen (approximately 90% of ankylosing spondylitis patients express the HLA-B27 genotype), this antigen has not proved to be an adequate screening marker as only 5% of individuals with the HLA-B27 genotype contract the disease. Thus, HLA-B27 is not necessary to confirm the diagnosis [2].

Symptoms

Inflammatory spondyloarthropathies should be considered in any young adult patient who complains of insidious onset, progressively worsening, dull, thoracolumbar or lumbosacral back pain. Other characteristics that should raise suspicion for inflammatory-mediated axial disease include back pain that improves with exercise, shows no improvement with rest, and is responsive to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications and pain at night [3].

Ankylosing spondylitis can have a variable presentation, but sacroiliac pain is a common complaint along with progressive morning stiffness and prolonged stiffness after inactivity. Tendon and ligament attachment sites may become painful and swollen, and one third of patients may have hip or shoulder pain. Chest pain with deep breathing and eye pain with blurred vision, floaters, and photophobia are late symptoms of more severe disease [4]. Neurologic symptoms, such as paresthesias and motor weakness, are usually absent.

Physical Examination

The most typical findings on physical examination are signs of decreased spine mobility and pain at sites of ligament and tendon attachments. Tests of spinal mobility include the modified Schober test, finger to floor distance, cervical rotation, occiput to wall distance, and chest expansion. The modified Schober test is performed with the patient initially standing in erect position. The examiner identifies the posterosuperior iliac crest line (i.e., lumbosacral junction) and makes two midline marks, one 10 cm above the iliac crest line and one 5 cm below the iliac crest line. The patient is then instructed to perform forward trunk flexion while the examiner measures the distance between the two marks. Normal spinal mobility is indicated by an increase of more than 5 cm or a total distance of more than 20 cm; an increase of less than this would suggest limited lumbar spine mobility. The inability to touch the occiput to the wall while standing against it and the inability to expand the chest by more than 3 cm in full inhalation are late findings in the disease [5].

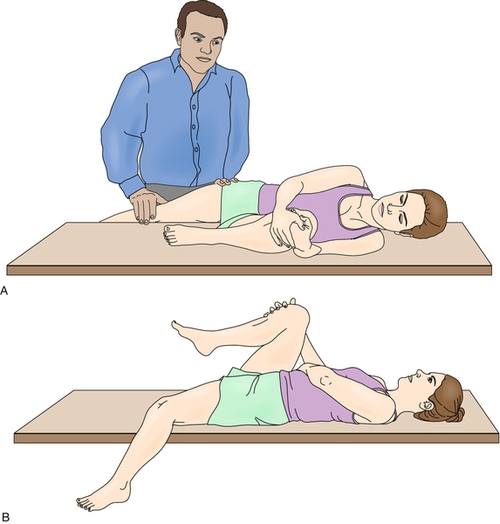

On palpation of the spine, the lower paraspinal muscles and sacroiliac joints may be tender. A Gaenslen test result may also be positive (Fig. 120.1). Palpation of extremities demonstrates pain at attachment sites of ligaments and tendon (enthesitis), particularly around the heel (e.g., calcaneal enthesitis) and knee (i.e., tibial tuberosity). Peripheral joint swelling and pain with decreased range of motion can be seen in 25% to 30% of patients. A discolored and edematous iris with circumferential corneal congestion occurs in iritis and anterior uveitis. The neurologic evaluation is typically normal with regard to motor, sensory, and reflex examination findings. Weakness may be noted, but it is usually associated with pain, loss of mobility, or disuse.

Functional Limitations

The functional limitations of the patient with ankylosing spondylitis are typically related to spine pain and immobility. The three best predictors of decreased spinal mobility are cervical rotation, modified Schober test, and finger to floor distance, although these measurements have not correlated with the patient’s assessment of disease activity [5,6]. Early in the disease process, decreased spine range of motion is secondary to back pain and muscle spasms. Most dysfunction is mild and self-limited, typically improving with treatment. In severe disease, positioning from hip flexion contractures, thoracic kyphosis, and loss of cervical rotation decrease patients’ ability to view activities in front of them and side to side. The most commonly reported activity limitations are interrupted sleeping, turning the head while driving, carrying groceries, and having energy for social activities [7]. Limitations in chest wall motion lead to a reliance on diaphragmatic breathing and a secondary drop in aerobic capacity. Pain, posture, and functional impairments can also significantly affect sexual relationships [8].

The Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index and the Dougados Functional Index are functional assessment tools used by clinicians specializing in the care of patients with ankylosing spondylitis that provide a measure of daily function [9–11]. Past studies have shown that approximately 90% of patients with ankylosing spondylitis remain employed, although recent evidence suggests that up to one third of patients experience some form of employment disruption because of pain and physical limitations [4,6,12].

Diagnostic Studies

There is a well-documented lag time between initial onset of symptoms and diagnosis that ranges from 7 to 11 years [13]. Given the lack of specific signs and symptoms for early ankylosing spondylitis, a high level of suspicion is required in young patients presenting with back pain. Laboratory investigation should include inflammatory markers: erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein [11]. Although neither is required for diagnosis and approximately 40% of patients will have normal values, the elevation of acute phase reactants can indicate severity, responsiveness to treatment, peripheral joint involvement, or extra-articular disease. HLA-B27 is present in 90% of patients with ankylosing spondylitis. A negative test result suggests milder disease with a better prognosis. Rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibodies are absent.

Radiography of the spine and pelvis is the standard imaging modality in diagnosis and assessment of disease, although computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging are more sensitive for detection of bone changes, especially early in the disease course and particularly in the assessment of the sacroiliac joints [14]. Spine radiographs show ossification of spinal ligaments and apophyseal joints, sclerosis, and syndesmophytes with eventual ankylosis that leads to the classic bamboo spine appearance. Pelvic (sacroiliac and hip) radiographs demonstrate symmetric involvement of the sacroiliac joints with bone erosions, sclerosis, and blurring of the subchondral bone plate eventually progressing to complete ankylosis. On the basis of the modified New York criteria for ankylosing spondylitis, radiographic features of moderate bilateral sacroiliitis or moderate to severe unilateral sacroiliitis plus one clinical feature are required for definite diagnosis of ankylosing spondylitis. Additional radiographic findings include bone erosions at entheses, symmetric and concentric joint narrowing, and subchondral sclerosis of the hip joints with ankylosis in severe disease. Once initial radiographs are abnormal, further radiographic progression correlates with worsening results of the modified Schober test, although it is recommended that assessment of spinal mobility be used as a proxy for radiographic evaluation [15].

Early computed tomography imaging findings demonstrate pseudowidening of the sacroiliac joints followed by sclerosis, narrowing, and ankylosis. Magnetic resonance imaging can show similar findings but also provides the additional benefit of revealing active inflammation. Sonography can be used to diagnose enthesitis and can also be particularly useful to guide therapeutic interventions and to follow disease progression [16,17].

Treatment

Initial

Evidence-based treatment guidelines must be tailored to the disease progression and functional impact on the individual with ankylosing spondylitis. The goals of management have been outlined by the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) and the Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society (ASAS) and should include concurrent medical, rehabilitation, and surgical treatment with the goals of optimizing pain control, maintaining maximal functional capacity with emphasis on spinal range of motion, reducing fatigue, and minimizing impact of extra-axial manifestations [18–20]. Given the variable presentation and progression of symptoms in each patient, an individualized program tailored to the patient’s specific needs is necessary.

From a medical standpoint, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are considered the first-line treatment of patients with ankylosing spondylitis. NSAIDs provide symptomatic relief and have been shown to slow radiographic progression [21–23]. The choice of NSAID is based on individual therapeutic response, compliance, and side effects. Continuous dosing (as opposed to intermittent administration of NSAIDs during periods of exacerbation) is the favored dosing regimen based on the most recent 2010 ASAS/EULAR recommendations; this dosing regimen has been shown to slow structural damage with only marginal increase in side effects [19,22,24].

The recent discovery of biologics has revolutionized the treatment of rheumatologic diseases [25]. Specifically, tumor necrosis factor-α antagonists (infliximab, etanercept, adalimumab, and golimumab) have demonstrated clinical effectiveness in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis [20]. The choice of tumor necrosis factor-α blocker is based on individual therapeutic response and other factors, such as the presence of extra-axial manifestations or concomitant inflammatory bowel disease. Other disease-modifying agents have shown limited efficacy and are not generally recommended in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis with the exception of sulfasalazine, which can be used in cases with a predominance of peripheral disease, inflammatory bowel disease, or psoriasis [20,26]. Pulsed methylprednisolone may be effective for NSAID-resistant flares, although long-term use is not generally recommended because of concern for osteoporosis [19,27]. Pamidronate, when it is used to treat associated osteoporosis, may also decrease ankylosing spondylitis disease progression [28].

Rehabilitation

The benefits of exercise for patients with ankylosing spondylitis are well documented [29]. Individualized programs should include activities to optimize aerobic capacity, flexibility, and pulmonary function [30–32]. Hip range of motion increases with regular stretching with use of the contraction-relaxation-stretching technique. Strengthening of back and hip extensors should follow the flexibility exercises. Aerobic activities may maintain chest expansion. However, an exercise stress test should be considered before an aerobic program if aortic insufficiency is suspected [31].

Despite the well-documented benefits of exercise programs, patients with ankylosing spondylitis are poorly compliant, and not surprisingly, the benefits of these programs are lost once the exercise is discontinued. There is no evidence that a particular type of exercise is superior to another, although specific exercise programs that target strengthening and flexibility of shortened muscle chains show promise [33]. One particular area that has clearly shown benefit is the setting in which the program is performed [19]. A physical therapy supervised group was superior to a home exercise program and both were superior to no intervention for improvements in pain, function, mobility, and patient global assessment. Group exercise also demonstrated improved compliance [29,34,35].

Spa therapy and balneotherapy can be safely recommended and have shown moderate benefit for treatment of pain and improving the patient’s assessment of disease activity [36]. Splinting and spinal orthoses are generally not effective. Foot orthotics can help with calcaneal enthesopathies. A firm mattress may help with sleep, along with a small cervical pillow that will help maintain cervical lordosis. Wide mirrors assist drivers with limited cervical mobility [32]. There are no data to support or to refute the use of diet, education, or self-help groups [19].

Procedures

Periarticular corticosteroid injections and fluoroscopically guided sacroiliac joint injections may help during NSAID-resistant flares or when NSAIDs are contraindicated [37]. Local injections for enthesopathies may be effective, but injections in and around the Achilles tendon insertion should be avoided.

Surgery

Hip and knee arthroplasties are effective for patients with intractable pain, limitations in mobility, and poor quality of life. Early referral to an orthopedic surgeon should be considered as joint replacement is optimal before progression to ankylosis. Age is not considered a limiting factor as young patients have fared well, and long-term studies have demonstrated that more than 50% of patients exceed a 20 + -year life span of their prosthesis [38,39]. Spinal osteotomy is an option for patients with severe kyphosis to improve horizontal vision and balance, although there is considerable risk [19,40].

Potential Disease Complications

Potential complications include iritis or uveitis, inflammatory bowel disease, aortic insufficiency, and aortic root dilation [41]. Osteoporosis (best evaluated with bone densitometry of the femur) is common, which increases risk of spine fracture and associated neurologic injury due to relatively minor trauma [42,43]. Recent evidence suggests an increased morbidity and mortality due to cardiovascular disease in patients with ankylosing spondylitis [44].

Potential Treatment Complications

NSAIDs may produce gastrointestinal and renal toxic effects [45]. Corticosteroids increase risk of osteoporosis. Tumor necrosis factor-α antagonists increase the risk of infection, including reactivation of latent tuberculosis. Total hip arthroplasty increases the risk of anterior dislocations. Spinal osteotomy carries the risk of paralysis and a mortality rate of up to 4% [40].