CHAPTER 12. Improving care

Joan McDowell and Derek Gordon

Introduction 281

The right people 281

The right time 283

The right place 284

The right care 285

Conclusion 289

References 290

Useful website addresses 291

ORGANISATION OF CARE

People with diabetes require support to manage their own condition; this must be provided by the right people, at the right time, in the right place and with the right care. As health care in the UK is funded from public taxes, there is a public responsibility to ensure that money is used appropriately to ensure the most effective use of resources. Within the UK, the NHS facilitates equity in service provision, although its translation at national level might vary according to the unique health needs of the four nations.

The UK, and Scotland in particular, are taken as the template for this chapter. However, it is acknowledged that some of the principles outlined here are of relevance to healthcare settings in different countries across the world. It is also acknowledged that the funding for health care in different countries will drive the manner in which care is provided and hence there will be variations of practice due to economic factors (Bakker & Bilo 2004, Pedrosa 2004, Urbancic & Koselj 2004).

THE RIGHT PEOPLE

People with diabetes need access to a wide variety of people to support them in their diabetes care. In the first instance, general practitioners are the gate-keepers to specialist expertise. People who are not registered with GPs are therefore denied this point of contact.

The current delivery of care within the UK determines that most people with type 2 diabetes can receive satisfactory care within the primary care setting where structured support is offered (Griffin & Kinmonth 2005). GPs in the UK work as independent practitioners and hence hold a separate contract with the government for delivery of services. The General Medical Services Contract has introduced a new method of funding primary care practitioners with financial incentives offered to GPs who deliver diabetes care and meet national quality standards. These include annual screening for diabetes complications and percentage of people with diabetes whose cholesterol is below government targets (Kenny 2004). This is one example of government policy directly impacting on practice delivery. A Cochrane systematic review was undertaken on interventions to improve the management of diabetes in primary care, outpatient and community settings. This concluded that interventions that were targeted at healthcare professionals and organisational interventions increased the continuity of care. The effect on outcomes for people with diabetes was less clear (Renders et al 2005).

People with type 1 diabetes or those requiring specialist support around different parameters of their care, e.g. pregnancy, the use of an infusion pump or complications of diabetes, normally require specialist services in secondary care. People with complex needs, e.g. renal dialysis, also require specialist support. For the individual with diabetes, regardless of the care setting, a multidisciplinary team including doctors, nurses, podiatrists and dieticians is there to provide care.

At times, it is carers who require support. All members of the healthcare team are encouraged to involve carers in all their communications as they have a central role in supporting the person with diabetes. As diabetes affects an individual’s whole lifestyle, it is important that his or her family and friends are aware of what the person is going through, the support available and what they can contribute to the person’s care.

COMMUNICATION BETWEEN PEOPLE

It is essential that all professionals who are involved in the care of those with diabetes communicate effectively with individuals with diabetes, their carers and also with each other. The use of information technology has greatly facilitated this process. The development of primary care and hospital information technology systems with a common data set has resulted in the development of SCI-DC (Scottish Care Information Diabetes Collaboration, see: www.show.scot.nhs.uk/crag/topics/diabetes/diabit/Q&A.doc). This allows the flow of clinical information between different members of the team without the normal delay met through more routine channels.

PROFESSIONAL’S KNOWLEDGE

All members of the healthcare team need to be up to date in their knowledge base of diabetes to provide evidence-based care to individuals. Although post-registration education is developing as a norm within the UK (Scottish Executive 2002) it is not yet mandatory. The Scottish Executive Health Department has set up an advisory committee on diabetes education that addresses the education of professionals. In America, The Declaration of the Americas (DOTA) has set up an education task group which has established the norms for diabetes education programmes for people with diabetes in the Americas (www.paho.org). This addresses organisational issues, the educational programme for people and the professional characteristics required.

VOLUNTARY ORGANISATIONS

Voluntary organisations have a major role to play in supporting people with diabetes. The mission of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) is to ‘prevent and cure diabetes and to improve the lives of all people affected by diabetes’. Through their auspices, people with diabetes can be linked with peers or professionals as required. The ADA is a non-profit-making organisation that funds research and provides information and other services to people with diabetes, their families, professionals and the public. The association also advocates for the rights of people with diabetes. It is, therefore, very similar to Diabetes UK, which was discussed in Chapter 11.

The Scottish Executive aims to ensure that the NHS meets the needs and wishes of people receiving care and treatment and that services were designed for this purpose (www.scotland.gov.uk/library3/health/pfpi-00.asp). One consequence of this was that, under the auspices of The Scottish Diabetes Group, the Patient Focus Public Involvement Group was set up. The aim of this group is to ‘drive forward the implementation of the patient focus elements of the Scottish Diabetes Framework (Scottish Executive 2002) and to support the development of patient-centred diabetes services throughout NHS Scotland’ (www.diabetesinscotland.org/diabetes). Hence, within Scotland, there is a voluntary patient group that directly impacts on health service delivery for people with diabetes.

THE RIGHT TIME

People with diabetes need to access care when they determine that it is needed. This care can take the form of advice or an intervention. For this, the role of NHS 24 in Scotland, or NHS Direct in England, is crucial as an advice call centre. Diabetes UK also provides advice and a help line that can be accessed at its website (www.diabetes.org.uk). Most specialist diabetes centres offer telephone access to individuals. Both primary and secondary care normally offer drop-in clinics for individuals who want to use them.

Knowledge is power and to ensure that people with diabetes are empowered to take control of their lives, education plays an important part. Differing educational models are offered at different times within the person’s journey with diabetes. Professionals working in countries who do not necessarily have the same resources for educational programmes can still offer some form of information days for people with diabetes provided the multidisciplinary team work together to plan and shape the programme (Pender 2005).

Within the UK, Diabetes UK has taken a lead in several initiatives and their website is a ready source of material (www.diabetes.org.uk). The Welsh Assembly has supported a grant for Diabetes UK that has enabled them to compile a database of resources for people whose first language is not English. This database is to assist health professionals and covers 33 languages (www.diabetes.org.uk/health/patient/cymru.htm). Although this is not an exhaustive list, it is an excellent starting point when caring for people with different cultural backgrounds.

Information technology can also aid in the dissemination of information and can ensure that it is immediately available during consultations. SCI-DC is one example of a system that supports this for professionals. The internet has revolutionised global communications and access to information. People can access websites at a time that is most convenient to them to answer their questions or to link with others. There are thousands of websites that address aspects of diabetes care. Professionals and lay people are cautioned to access only those that are of a reputable organisation as the quality of websites is not always assured.

The web has added benefits for people with diabetes and professionals as they can all access current research through e-journals. The NHS Education for Scotland e-library (www.elib.scot.nhs.uk) aims to manage a knowledge-base to support people with diabetes. This is considered essential to ensure high-quality person-centred care. Within the e-library there is a diabetes portal that, as well as managing the many databases of books and journals, allows for ongoing discussion around topical issues in diabetes care from people with diabetes, carers, Diabetes UK and professionals. People need an Athens login address before entering the e-library. Relevant web addresses have been interspersed throughout chapters in this book, although these are not exhaustive. Two readily accessible search engines for locating professional material on the web are PubMed and Google Scholar.

THE RIGHT PLACE

To support people with diabetes, advice and interventions need to be accessible to individuals. People with type 2 diabetes are more frequently offered such services within primary care, which is usually nearer to them geographically. Those with type 1 diabetes are usually offered care within their local specialist care setting. It is acknowledged, however, that within the UK, boat, train or plane journeys might be required to access specialist care facilities.

There are particular challenges to delivering care to people who are not in a position to autonomously access care. People who live in an institutionalised setting are not usually mobile enough to attend any care settings. Those residing in nursing homes or in long-term care are dependent on others to meet their health needs, which can be complex (Benbow et al 1997). People who are housebound might not have access to some services. Community nurses in particular are uniquely placed to provide support for those who are unable to access care within a GP’s practice (Forbes et al 2002, Harris 2005).

Prisoners with diabetes also have difficulty in accessing the same level of service as those living in the community (Meakin 2004). Given that the Department of Health in the UK aims to provide prisoners with the same level of care as those outside the prison, it would appear that there is still a lot of work to be done in this area (Balance 2005).

People who have other complex problems might also be reliant on others taking the lead role to ensure they receive the appropriate care. Those who have learning difficulties, other disease entities, or an addiction to alcohol or drugs might all experience problems in accessing care due to situations beyond their control.

We live in times of globalisation and most Westernised cities are multicultural in population groups. It is therefore essential that care is offered in a culturally sensitive way and in a culturally appropriate place. It might be necessary to hold clinics in a mosque or social club to meet the needs of particular population groups.

THE RIGHT CARE

INTERNATIONAL PERSPECTIVE

The World Health Organization (WHO) has developed a variety of documents detailing the standard and level of care that people with diabetes should expect (www.who.int/topics/diabetes_mellitus/en/) within an international framework. An international group of experts has also presented recommendations on quality indicators for diabetes care (Greenfield et al 2004). This demonstrates global collaboration to ensure that the right care is being made available for people with diabetes.

To improve care for people with diabetes requires several factors. There must first be a political will, nationally and internationally, to invest in making changes. There needs to be ongoing investment in health care, both for prevention and treatment, because of the projected pandemic of type 2 diabetes with its associated morbidity and mortality. For people with diabetes, early prevention of its complications has many cost-effective benefits. As well as enhancing people’s quality of life, prevention of complications ensures a person’s contribution to society is maintained.

There has also recently been a united call for a diabetes framework across Europe that would build on the UK Diabetes Frameworks mentioned below. This call has come from Diabetes UK, the International Diabetes Federation-European Region and the Federation of European Nurses in Diabetes (Diabetes Update 2004).

Throughout the 1990s there were many changes in the UK organisation of diabetes care (Gordon & McDowell 1996) that aims to ensure that the right care is offered to people with diabetes. In the late 1990s, the UK Government launched a programme of National Service Frameworks (NSF) for Diabetes. These NSFs span the four countries of the UK: Scotland, Northern Ireland, England and Wales.

The aim of these NSFs was to set national minimum standards of diabetes care through raising the quality of health services and reducing geographical variations in the delivery of care. The scope of the NSFs includes prevention, diagnosing and management of diabetes and its complications long term. The progress of the four NSFs has been variable but in due course they have all produced strategic implementation plans:

▪Scottish Executive (2002): Scottish Diabetes Framework

▪Department of Health (2003): National Service Framework for Diabetes Delivery Strategy

▪Department of Health (2002): National Service Framework for Diabetes Standards in Wales

▪Diabetes UK and Clinical Resource Efficiency Support Team (CREST) (2001): Northern Ireland Task Force on Diabetes.

The implementation of the plans is the responsibility of local health boards, which have devolved these to professional groups who comprise a managed clinical network.

Previously, the UK health service operated with a hierarchical structure and an internal market. With the change in government at the end of the 1990s, networks were considered to be a way forward from the internal competition to collaborative working (Powell 1999). Managed clinical networks are characterised by an ethos of trust, reciprocity, understanding and loyalty. They operate as a form of clinical governance. By mapping current service provision and sharing knowledge, resources and information, better use can be made of scarce resources and they can reduce inequities and improve access to care.

SCOTTISH PERSPECTIVE

Health became a devolved issue in Scotland with the establishment of a Scottish Parliament. In many ways, Scotland has therefore been able to take a lead within the UK on health issues. The Scottish Diabetes Framework (SDF) established building-blocks for diabetes care (Scottish Executive 2002). These blocks were prioritised to ensure they would attract new government funding. One such example was a national retinal screening programme. This was set in motion with pump-primed funding for establishing managed diabetes clinical networks in each of the 15 area health boards. Hence, within Scotland, eye screening is undertaken on a national basis as opposed to local initiatives.

The Scottish Executive thereafter established the Scottish Diabetes Group (SDG) with the remit of implementing the SDF and monitoring the same. The SDG has established a variety of subgroups that address education, research and monitoring of the SDF implementation plan for example (www.diabetesinscotland.org/diabetes). This latter subgroup is the Scottish Diabetes Survey Monitoring Group.

The Scottish Diabetes Survey Monitoring Group provides an annual report of clinical parameters of people with diabetes for all the health boards within Scotland (http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Publications/2004/10/20023/44194#1). The supply of this information is an obligation on the health boards and it is submitted anonymously to a central source. Initially, structures and processes were submitted but now outcomes of care are included. This allows the determinants of care to be monitored and assessed.

As stated earlier, there must be a political drive to change healthcare practice. The Scottish Parliament has recently set up a cross-party group in diabetes. This group aims to provide a platform for politicians regardless of their party affiliations, people with diabetes, organisations with an interest in diabetes and professionals to discuss and promote good practice. It is also a forum where issues can be raised that can directly influence policy debates within the Scottish Parliament (www.scottish.parliament.uk/msp/crossPartyGroups/groups/cpg-diabetes.htm).

QUALITY CONTROL

The Audit Commission is an independent body within the UK that is responsible for ensuring that public money is spent economically, efficiently and effectively. It aims to promote good practice and to focus resources on those people who need public services most. The Audit Commission applies to England and Wales and information on its outcomes can be found on its website (www.audit-commission.gov.uk)

The NHS Quality Improvement Scotland (NHSQIS) is a special health board in Scotland with the remit of improving care for people in Scotland (www.nhshealthquality.org). It aims to:

▪ provide clear advice and guidance on effective clinical practice based on a review of available evidence

▪ set clinical and non-clinical standards of care

▪ review and monitor performance of the NHS in Scotland

▪ run development programmes for staff

▪ promote clinical risk management.

Under the auspices of NHSQIS, a standards development unit has been established. Its remit is to develop and monitor standards on a national basis. Crucially, people with diabetes are involved in this process and each team reviewing the standards has lay members. Under the auspices of NHSQIS, there are clinical standards in diabetes.

The individual who has diabetes within the UK should enjoy the standard of care set out in the above documents. However, although standards are set and care is delivered in a variety of ways and in different settings, individuals also have their own unique care needs. The right care for an individual with diabetes must take into account that person’s own cultural and religious perspective of life and attempt to balance this with current clinical guidelines.

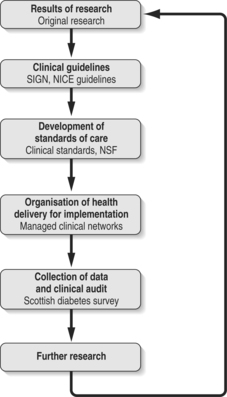

IMPACT OF RESEARCH ON ORGANISATIONAL ISSUES

Research plays an important role in the delivery of care. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) Research Group (1993) and the UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) (1998) are two large studies that have had a major impact on the delivery of care. Both these clinical studies show that the goal of all care is to work with the individual to reduce both blood glucose to near normal levels and, blood pressure. Research leads to the development of clinical standards and an emerging evidence base. The Diabetes Trial Unit based in Oxford University (www.dtu.ox.ac.uk) is a centre for diabetes research and its website informs readers of ongoing research and outcome summaries for practical use.

Within Scotland, the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN; www.sign.ac.uk) was set up by the Royal Colleges of Medicine to develop research evidence based guidelines for the NHS in Scotland, not specifically for diabetes. SIGN first produced a series of diabetes guidelines in 1996; these were updated in 2001 (SIGN 2001) and can be accessed from the website. More recently, SIGN has become part of NHS Quality Improvement Scotland (www.nhshealthquality.org).

SIGN was Scotland’s response to the St Vincent Declaration (Krans et al 1995). This was a WHO response to the mortality and morbidity of diabetes; the member countries agreed to take positive action to reduce the complications of diabetes. To commence this process, it was important to establish a research evidence base of interventions that are known to affect clinical outcomes. This was established under the auspices of SIGN and is maintained and updated every 5 years.

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) in the UK is an independent organisation that is responsible for providing national guidance on the promotion of good health and the prevention and treatment of ill health. The NICE develop and update various guidelines for diabetes care that can be accessed from their website (www.nice.org.uk). NICE also has the function of determining the cost effectiveness of treatments.

The right care is continually evolving in a cyclical manner. It requires the setting up of structures and processes to support it. Figure 12.1 shows the integration between research and audit using exemplars detailed above.

|

| Fig. 12.1Development of diabetes |

Several tiers of support are required if the appropriate treatment is to reach the individual with diabetes. People with diabetes are the experts in their own care. Their family, friends and support networks are their informal carers who are travelling with them on their journey through life. However, the actual living with diabetes can only be undertaken by individuals themselves.

Any organisation of health care must ensure that the needs of people living with diabetes are central and at the core of all health service delivery. Hence, it can be seen that the organisation of diabetes care has to consider who the right person is to deliver the care. This might be the individual with diabetes, his or her family and friends or healthcare professionals.

The timing of care is crucial to support individuals in managing their own diabetes. It is vital that specialist services are available when required. Likewise, it is also vital that when a person is ready to make a change in their diet or exercise, that the right support is offered at this time as well. As people travel through life and face many different challenges, it is important that they are equipped with the right care to manage their diabetes, on an ongoing basis.

REFERENCES

K Bakker, HJG Bilo, Diabetes care in the Netherlands: now and in the future, Practical Diabetes International 21 (2) (2004) 88–91.

Balance, Prisoner cell block D (2005 March–April) 28–32.

SJ Benbow, A Walsh, GV Gill, Diabetes in institutionalised elderly people: a forgotten population? British Medical Journal 314 (1997) 1868–1869.

Department of Health (DH), National service framework for diabetes standards in Wales. (2002) DH, Wales .

Department of Health (DH), National service framework for diabetes delivery strategy. (2003) DH, London .

Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) Research Group, The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, New England Journal of Medicine 329 (1993) 977–986.

Diabetes UK and Clinical Resource Efficiency Support Team (CREST), Northern Ireland task force on diabetes. (2001) CREST, Northern Ireland .

Diabetes Update 2004 A framework for diabetes in Europe. Diabetes Update, Winter:7

A Forbes, J Berry, A While, et al., Issues and methodological challenges in developing and evaluating health-care interventions for older people with diabetes mellitus, part 1, Practical Diabetes International 19 (2) (2002) 55–59.

D Gordon, J McDowell, The organisation of diabetes care, In: (Editors: JRS McDowell, D Gordon) Diabetes: caring for patients in the community 249-261 (1996) Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh.

S Greenfield, A Nicolucci, S Mattke, Selecting indicators for the quality of diabetes care at the health systems level in OECD countries. OECD health technical papers no 15, Online. Available: www.oecd.org/dataoecd/28/34/33865546.pdf (2004).

S Griffin, AL Kinmonth, Systems for routine surveillance for people with diabetes mellitus. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews issue 4, Online. Available: www.cochrane.org/reviews/en/ab000541.html (2005).

G Harris, Diabetic yearly reviews: the role of DNs, Journal of Community Nursing 19 (7) (2005) 12–17.

C Kenny, Primary diabetes care: yesterday, today and tomorrow, Practical Diabetes International 21 (2) (2004) 65–68.

HMJ Krans, M Porta, H Keen, K Staehr Johansen, Diabetes care and research in Europe: the St Vincent Declaration action programme. Implementation document. (1995) World Health Organization, Rome .

J Meakin, Diabetes behind the bars. Diabetes Update Winter:18–20, Online. Available: www.diabetes.org.uk/update/winter04/downloads/Prinsoners.pdf (2004) .

HC Pedrosa, Diabetes care in Brazil: now and in the future, Practical Diabetes International 21 (2) (2004) 86–87.

S Pender, Planning and information day for people with diabetes, Nursing Times 101 (31) (2005) 35–37.

M Powell, New Labour and the ‘third way’ in the British NHS, International Journal of Health Services 29 (1999) 353–370.

Renders CM, Valk GD, Griffin S et al 2005 Interventions to improve the management of diabetes mellitus in primary care, outpatient and community settings. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews issue 4. Art. No. CD001481. DOI: 10.1002/14651858. CD001481. Online. Available: www.cochrane.org/reviews/en/ab001481.html

Scottish Executive, Scottish diabetes framework. (2002) Scottish Executive, Edinburgh .

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN), SIGN 55: management of diabetes. (2001) SIGN, Edinburgh .

UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group, Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33), Lancet 352 (1998) 837–853.

V Urbancic, M Koselj, Diabetes care in Slovenia: now and in the future, Practical Diabetes International 21 (2) (2004) 92–94.

USEFUL WEBSITE ADDRESSES

www.audit-commission.gov.uk www.audit-commission.gov.uk: the Audit Commission in the UK.

www.childrenwithdiabetes.com www.childrenwithdiabetes.com: a support site drawing largely from the US. It is aimed at parents and children with diabetes.

www.diabetes.org.uk www.diabetes.org.uk: Diabetes UK is an organisation that functions to meet the needs of people with diabetes and healthcare professionals caring for people with diabetes.

www.diabetes.org www.diabetes.org: American Diabetes Association.

www.diabetes-healthnet.ac.uk www.diabetes-healthnet.ac.uk: the Tayside Diabetes Network, which contains several links to other relevant sites, including Scottish Care Information Diabetes Collaboration (SCI-DC).

www.diabetesinscotland.org www.diabetesinscotland.org: website for the Scottish Diabetes Group, with several excellent links.

www.dtu.ox.ac.uk www.dtu.ox.ac.uk: the UK Diabetes Trial Unit based at the University of Oxford.

www.easd.org www.easd.org: the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

www.elib.scot.nhs.uk www.elib.scot.nhs.uk: the NHS Scotland e-library, which contains a diabetes portal.

www.fend.org www.fend.org: Federation of European Nurses in Diabetes.

www.idf.org www.idf.org: International Diabetes Federation.

www.jrdf.org www.jrdf.org: Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation International.

www.nhshealthquality.org www.nhshealthquality.org: NHS Quality Improvement Scotland.

www.nice.org.uk www.nice.org.uk: the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, which works on behalf of the National Health Service in the UK.

www.paho.org www.paho.org: the Pan American Health Organization, which includes diabetes within its topic area of non-communicable diseases.

www.scotland.gov.uk www.scotland.gov.uk: the Scottish Executive.

www.scottish.parliament.uk www.scottish.parliament.uk: the Scottish parliament.;

www.show.scot.nhs.uk www.show.scot.nhs.uk: NHS Scotland.

www.sign.ac.uk www.sign.ac.uk: the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN), which develops and disseminates national clinical guidelines with recommendations for effective practice based on current evidence.

www.who.int/topics/diabetes_mellitus/en www.who.int/topics/diabetes_mellitus/en: the World Health Organization.