CASE 12 Excessive Coronary Tortuosity

Cardiac catheterization

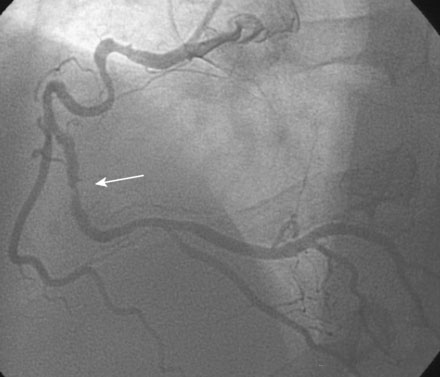

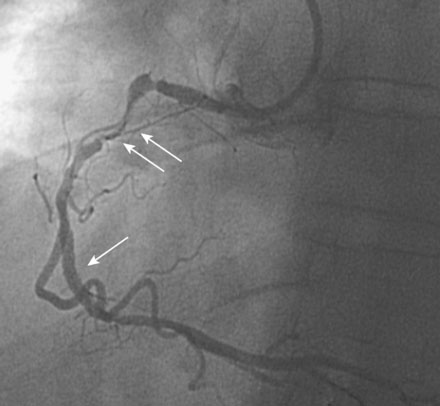

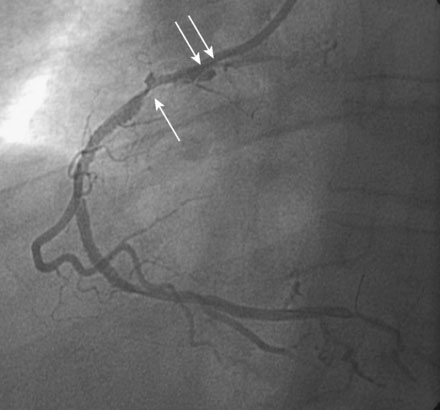

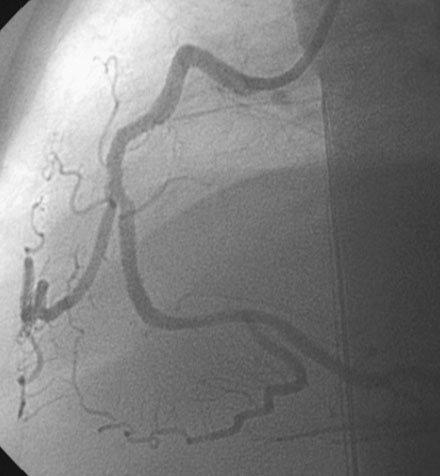

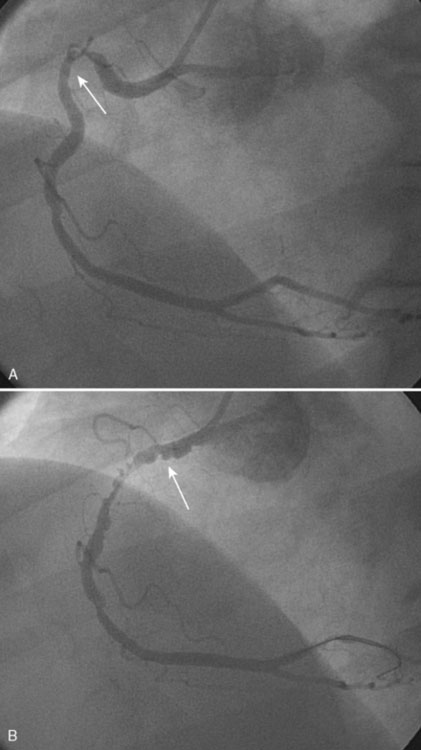

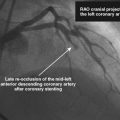

The culprit lesion involved the right coronary artery. There was a severe stenosis in the midportion of the right coronary artery past an extremely tortuous segment of the artery (Figures 12-1, 12-2, 12-3 and Video 12-1). There was moderate disease in the left anterior descending artery (Figures 12-4, 12-5).

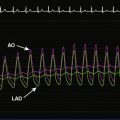

Based on the angiogram and the clinical presentation, the patient’s physician decided to proceed with a percutaneous intervention of the right coronary artery. The severe tortuosity of the proximal right coronary concerned the operator and, anticipating difficulty passing wires, balloons, and stents around the tortuous segment, the operator decided to use a supportive guide catheter and engaged the right coronary artery with a 6 French extra-support right guide catheter (Cordis, XBRCA). Procedural anticoagulation was accomplished with a bolus of unfractionated heparin and a double bolus plus infusion of eptifibatide. The operator crossed the lesion with a floppy-tipped, 0.014 inch guidewire. This wire successfully straightened the proximal tortuosity and allowed passage of a 2.5 mm diameter by 15 mm long compliant balloon (Figure 12-6). The operator chose a 3.0 mm diameter by 18 mm long bare-metal stent. Advancing the stent to the desired segment of the artery proved very difficult. Ultimately, this stent was successfully delivered to the lesion (Figure 12-7 and Video 12-2). The post-stent angiogram revealed a new and concerning lesion proximal to the stent. This segment of the artery straightened substantially with the floppy-tipped guidewire and the physician was unsure if the angiographic appearance represented a “pseudolesion” due to straightening of the tortuous segment by the guidewire or if it represented an injury to the artery from the vigorous attempts at passing the stent. The operator decided to pass another 3.0 mm by 18 mm stent, but was unable to advance it to the desired location (Figure 12-8). After positioning an extra-supportive guidewire (Mailman, Boston Scientific) alongside the first wire, and after deeply inserting the guide catheter, the operator successfully delivered this stent. The angiogram obtained after the second stent was placed showed that the additional wire further straightened the artery (Figure 12-9) creating a prominent pseudolesion. However, in addition to the pseudolesion, there was retention of contrast at the ostium that was concerning for a guide catheter dissection (Video 12-3). A third 3.5 mm diameter by 23 mm long bare-metal stent was placed over this segment. The final angiographic result in multiple projections and with the guidewires removed is shown in Figures 12-10, 12-11 and Videos 12-4, 12-5.

Discussion

Marked tortuosity of the coronary arteries is often seen in patients with longstanding hypertension and in elderly individuals. Tortuosity impairs the operator’s ability to advance guidewires, balloons, and stents. Even floppy-tipped guidewires are sometimes difficult to position, and the operator may encounter considerable loss of torque control after advancing past one or more sharply angled and tortuous segments. The operator must achieve appropriate guide catheter support before beginning a PCI on a tortuous coronary. This typically requires the use of guides with larger bores and aggressive curves. If a high-torque floppy guidewire is not successfully advanced, a hydrophilic wire may prove valuable as this type tends to “float” down the artery and requires less manipulation. Many operators employ extra-supportive wires to help straighten the tortuous curves and help deliver equipment. However, the extra stiffness of their shafts may hinder their delivery. In these cases, many physicians use a floppy-tipped wire as the primary wire and the stiffer, supportive wire as a second or “buddy” wire.1 Compliant balloons are usually deliverable despite severe tortuosity. Stents, however, may not pass easily around the curves. Tricks for success include the use of an aggressive guide, employment of extra-supportive guidewires or “buddy” wires1 and adequate lesion predilatation. In addition, it is often wise to use multiple short stents instead of a single long stent to cover the diseased segment. Finally, drug-eluting stents are sometimes more difficult to pass than the thin-strut, bare-metal stents.

Marked vessel tortuosity increases the risk of PCI-related complications. Difficulty with wire manipulation may result in intimal injury or vessel dissection. Balloon angioplasty of a tortuous and angulated segment often leads to dissection. This could pose a serious problem if the operator cannot subsequently deliver a stent. Tortuosity is a well-recognized risk factor for coronary perforation from rotational atherectomy.2 Finally, the use of aggressive guide catheters necessary to provide adequate support may also result in guide-related injury to the proximal coronary as observed in this case.

In the setting of significant vessel tortuosity, guidewires and balloon catheters may straighten the artery and create “pseudolesions.”3–6 This angiographic artifact represents an invagination or crumpling of the redundant segments of the vessel from straightening, and has also been termed “the accordion phenomenon.”6 Characteristically, it appears as the development of a “new” lesion after the guidewire has been placed but appears smooth and beaded (Figure 12-12). The unenlightened PCI operator may misinterpret these artifacts as a dissection, thrombus, or spasm, which often leads to the use of additional (and unnecessary) stents. As displayed in this case, pseudolesions are commonly observed in the right coronary artery, but have also involved the left anterior descending, circumflex arteries, and left internal mammary grafts.

Guidewire removal restores the artery to its original configuration and resolves the pseudolesion. Fearing a dissection, many physicians are reluctant to do this as they are not entirely confident that the angiographic appearance is solely due to straightening artifact. Withdrawal of the guidewire so that just the floppy-tipped portion is across the area of concern is one technique offered to prove that the apparent lesion is an artifact and not a dissection without giving up access to the distal lumen.7

1 Burzotta F., Trani C., Mazzari M.A., Mongiardo R., Rebuzzi A.G., Buffon A., Niccoli G., Biondi-Zoccai G., Romagnoli E., Ramazzotti V., Schiavoni G., Crea F. Use of a second buddy wire during percutaneous coronary interventions: a simple solution for some challenging situations. J Invasive Cardiol. 2005;17:171-174.

2 Cohen B.M., Weber V.J., Relsman M., Casale A., Dorros G. Coronary perforation complicating rotational ablation: the U.S. multicenter experience. Catheter Cardiovasc Diagn Suppl 3 1996:55-59.

3 Tenaglia A.N., Tcheng J.E., Phillips H.R., Stack R.S. Creation of pseudo narrowing during coronary angioplasty. Am J Cardiol. 1991;67:658-659.

4 Hays J.T., Stein B., Raizner A.E. The crumpled coronary: an enigma of arteriographic pseudopathology and its potential for misinterpretation. Catheter Cardiovasc Diagn. 1994;31:293-300.

5 Doshi S., Shiu M.F. Coronary pseudo-lesions induced in the left anterior descending and right coronary artery by the angioplasty guide-wire. Int J Cardiol. 1999;68:337-342.

6 Muller O., Hamilos M., Ntalianis A., Sarno G., DeBruyne B. The accordion phenomenon. Lesson from a movie. Circulation. 2008;118:e677-e678.

7 Chalet Y., Chevalier B., el Hadad S., Guyon P., Lancelin B. “Pseudo-narrowing” during right coronary angioplasty: how to diagnose correctly without withdrawing the guidewire. Catheter Cardiovasc Diagn. 1994;31:37-40.