CHAPTER 12

Biceps Tendinopathy

Brian J. Krabak, MD, MBA, FACSM

Definition

First documented in 1932, the term biceps tendinitis was used to describe inflammation, pain, or tenderness in the region of the biceps tendon [1]. More recently, tendinitis has been replaced by the term tendinopathy to reflect the nature of injury secondary to inflammation of the tendon sheath (–itis) versus degeneration of the tendon (–osis) [2,3]. Both represent overuse injuries to the biceps tendon, which helps prevent superior translation of the humeral head during shoulder abduction and is intimately associated with the labrum [4]. The biceps tendon works in concert with the rest of the shoulder muscles to maintain mobility and function. Injury to or compromise of a single muscle of the dynamic shoulder stabilizers can adversely affect other muscles and impair function of the entire joint.

Primary biceps tendinitis describes isolated inflammation of the tendon as it runs in the intertubercular groove; it typically occurs in the younger athletic populations [4]. The precipitating forces in primary biceps tendinitis are multifactorial, including acute repetitive overuse and secondary impingement due to scapular dyskinesis, unilateral instability, and multidirectional shoulder instability [5]. A flat medial wall or shallow bicipital groove can predispose to subluxation of the long head tendon, increasing risk for inflammation [6]. On the other hand, bicipital tendinosis is typically seen in the older population (i.e., athletes older than 35 years or nonathletes older than65 years) and more commonly than primary biceps tendinitis [1,5]. Studies have found that up to 95% of patients with bicipital tendinosis have associated rotator cuff disease [7].

Symptoms

Biceps tendinopathy usually is manifested with complaints of anterior shoulder pain that is worse with activities involving elbow flexion [2]. Pain usually localizes to the bicipital groove with occasional radiation to the arm or deltoid region. Often, pain will also occur with prolonged rest and immobility, particularly at night. The throwing athlete often describes pain during the follow-through of a throwing motion and may feel a “snap” if the tendon subluxes in the groove [4]. Attention should be given to onset, duration, and character of the pain. Some individuals present with only complaints of fatigue with shoulder movement. A history of prior trauma, athletic and occupational endeavors, and systemic diseases should be considered in evaluating the shoulder. Patients with accompanying “impingement syndrome” often complain of a “pinching” sensation with overhead activities and a “toothache” sensation in the lateral proximal arm. The pain can be difficult to separate from impingement or rotator cuff syndrome [5].

Physical Examination

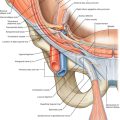

The physical examination begins with adequate inspection of the shoulder and neck region. Attention is given to prior scars, structural deformities, posture, and muscle bulk. Determination of the exact location of pain can be helpful for diagnosis. Biceps tendinopathy commonly presents with palpable tenderness over the bicipital groove (Fig. 12.1). Side-to-side comparisons should be made because the tendon is typically slightly tender to direct palpation. Tenderness over the lateral aspect of the shoulder suggests bursitis, tendinopathy, or strain of the deltoid muscle. Caution should be used as the accuracy for palpation of the biceps tendon was 5.3% in residents and fellows [8]. Motion limitation is not seen in isolated tendinopathies but is often seen in concomitant degenerative joint diseases, impingement syndromes, tendon tears, and adhesive capsulitis. Shoulder range of motion may be limited if the rotator cuff is involved. The findings on neurologic examination should be normal, including sensation and deep tendon reflexes. On occasion, strength is limited by pain or disuse. Assessment of the kinetic chain, including scapular stability and spine stabilization, is important.

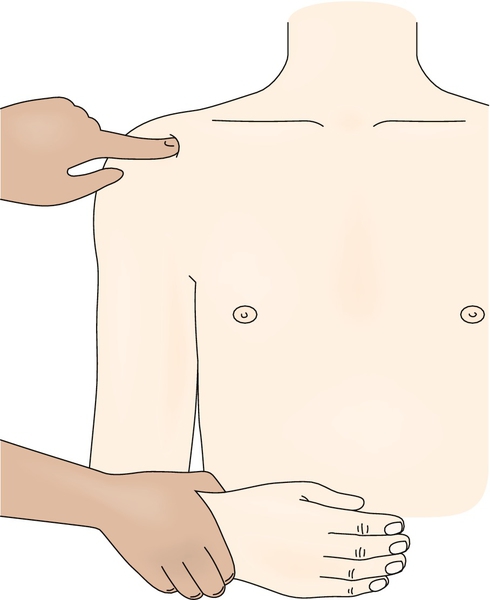

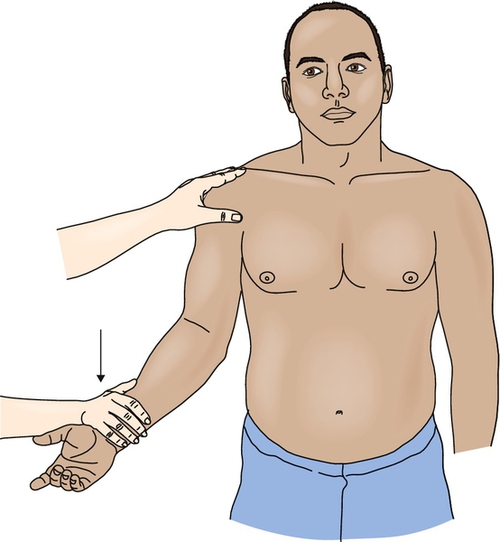

Special tests of the shoulder should be performed routinely. The Speed and Yergason tests (Figs. 12.2 and 12.3) are often used to help evaluate for bicipital tendinopathy. Unfortunately, a recent meta-analysis suggests that these tests are not sensitive (Speed test, 50%-63%;Yergason test, 14%-32%) or specific (Speed test, 60%-85%; Yergason test, 70%-89%) for diagnosis of biceps tendinopathy [9]. Impingement tests and supraspinatus tests will help assess for any concurrent rotator cuff tendinopathy. Other maneuvers to assess for instability (anterior apprehension, anterior-posterior load and shift), labral disease (O’Brien test), and acromioclavicular joint arthritis (scarf test) should be performed.

Functional Limitations

Biceps tendinitis may cause patients to limit their activities at home and at work. Limitations may include difficulty with lifting and carrying groceries, garbage bags, and briefcases. Athletics that involve the affected arm, such as swimming, tennis, and throwing sports, may be curtailed. Pain may impair sleep.

Diagnostic Studies

Biceps tendinopathy is generally diagnosed on a clinical basis, but imaging studies are helpful to exclude other pathologic processes. Plain radiographs are usually normal [1]. They can, however, show calcifications in the tendon and degenerative disease of the joint that may predispose to tendinitis. The Fisk view is used in evaluating bicipital tendinopathy to assess the size of the intertubercular groove. This may help determine whether there is a relative risk for development of recurrent subluxation of the tendon, which is seen in individuals with short and narrow margins of the intertubercular groove [10].

Ultrasonography can be extremely helpful and a cost-effective way to evaluate the biceps and rotator cuff tendons. Ultrasound can detect increased fluid in the biceps tendon sheath and evidence of tendinosis. In addition, ultrasound allows dynamic evaluation of the shoulder region to better assess biceps tendon subluxation. Recent research suggests that ultrasound of the shoulder is more accurate in confirming a normal biceps tendon or full-thickness tear but less accurate in the diagnosis of partial-thickness tears [11].

Magnetic resonance imaging can detect partial-thickness tendon tears, examine muscle substance, evaluate soft tissue abnormalities and labral disease (magnetic resonance arthrography), and assess for masses. In biceps tendinitis, increased signal intensity is seen on T2-weighted images [12]. However, this finding is also seen with partial tears of the tendon. Tendinosis is manifested with increased tendon thickness and intermediate signal in the surrounding sheath. Arthroscopy is a useful procedure for the evaluation of intra-articular disease but does not play a role in isolated tendinitis.

Treatment

Initial

The treatment of biceps tendinopathies involves activity modification, anti-inflammatory measures, and heat and cold modalities [2,4]. Overhead activities and lifting are to be avoided initially. Workstation assessment and modification can be helpful for laborers. Evaluation of athletic technique and training adaptations are important in athletes. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can assist with decreasing the pain and inflammation in treating tendinitis but do not play a role in tendinosis. Medications to increase blood flow to the tendon (i.e., nitro patches) may facilitate recovery. Ice is helpful after exercise for minimizing pain [3,4]. Moist heat can be useful before activity. Other modalities, such as iontophoresis and electrical stimulation, have been used, but there are no clinical trials supporting their efficacy.

Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation for biceps tendinopathy is similar to that for rotator cuff tendinopathy (see Chapter 16). Moreover, because biceps tendinitis rarely occurs in isolation, it is important to rehabilitate the patient by accounting for all of the shoulder disease that is present (e.g., instability, impingement) [1,2]. Shoulder stretching helps maintain or improve range of motion and is emphasized in all important shoulder movements of abduction, adduction, and internal and external rotation. Posterior capsule stretching is also important, particularly when impingement syndrome is also present. Once full, pain-free active range of motion is achieved, progressive resistance exercises are used to strengthen the dynamic shoulder and spine stabilizers, progressing from static to dynamic exercise as tolerated [4]. Eccentric strengthening exercises may be beneficial for biceps tendinopathy, but more research is needed. Overhead and shoulder abduction activities should be avoided early in treatment because they can exacerbate symptoms. Scapular and spine stabilization exercises should be introduced once biceps strength improves. The exercise program should progress to sport-specific functional activities, when appropriate. Athletes may return to play, gradually, when pain is minimal or absent [4].

Procedures

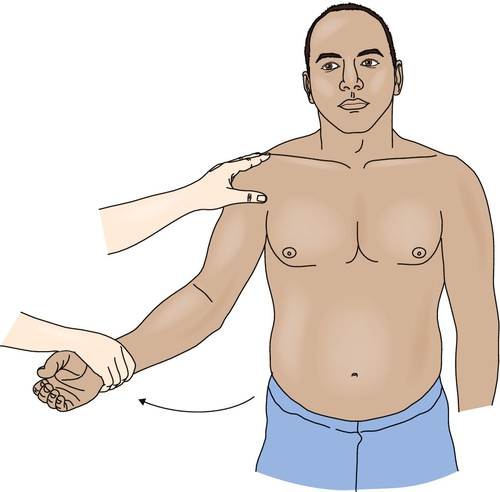

Steroid injections are a potentially useful adjunct for biceps tendinitis (Fig. 12.4) but should probably be avoided in cases of tendinosis. The goal of an injection would be to diminish pain and inflammation while facilitating the rehabilitation treatment program. Injections must be used judiciously to avoid weakening of the tendon substance. Ideally, injections should be performed under ultrasound guidance to improve accuracy and to avoid complications from injecting the tendon [13]. Immediate postinjection care includes icing for 5 to 10 minutes, and the patient may continue to apply ice at home for 15 to 20 minutes, two or three times daily, for several days. The patient should be instructed to avoid heavy lifting or vigorous exercise for 48 to 72 hours after injection. Injection of biologics (autologous blood and platelet-rich plasma) is potentially promising but needs further research to better define its utility [14]. Depending on the concurrent shoulder disease, other injections may also be useful (e.g., subacromial) [15].

Surgery

Surgery is generally not indicated for isolated biceps tendinitis. However, biceps tenodesis in conjunction with acromioplasty in chronic, refractory cases and in those cases associated with rotator cuff impingement has been found to have good results [16]. Tenotomy of the long head of the biceps for chronic tendinitis remains controversial, and long-term results are unknown [16,17].

Potential Disease Complications

Progressive biceps tendinitis and pain can lead to diminished activity, rotator cuff disease, and adhesive capsulitis. Compensatory problems with other tendons can develop because of their interdependence for proper shoulder movement. The development of myofascial pain of the surrounding shoulder girdle muscles is another common complication in shoulder tendinopathy.

Potential Treatment Complications

The exercise program should be properly supervised initially to prevent aggravation of tendinitis of other muscle groups. Analgesics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have well-known side effects that most commonly affect the gastric, hepatic, and renal systems. Repeated steroid injections in or near tendons could result in tendon rupture and should be performed under ultrasound guidance, whenever possible.