CHAPTER 119

Lower Limb Amputations

Definition

In 2005, an estimated 1.6 million persons in the United States were living with loss of a limb, of whom 65% have had a lower limb amputation [1]. Vascular conditions account for most cases of amputation (54%), with two thirds of these having a secondary diagnosis of diabetes [2]. Lower limb amputations account for 97% of all dysvascular amputations. More than half of dysvascular amputations are major lower limb amputations (transfemoral, 25.8%; transtibial, 27.6%) [2,3]; 42.8% involve other levels (ray, toes). Most of these amputations occur in people aged 60 years and older. There are approximately 82,000 nontraumatic diabetes-related lower extremity amputations each year [3]. Trauma is the next most common cause of lower extremity amputation (22%), followed by tumors (5%). However, in children aged 10 to 20 years, tumor is the most common cause of both upper and lower extremity amputations. Male amputees outnumber female amputees 2.1:1 in disease and 7.2:1 in trauma [4]. Across all causes, 42% of the persons living with the loss of a limb are 65 years or older; 65% are men, and 42% are nonwhite [2].

Symptoms

The postoperative or post-traumatic sequela of an amputation is that the patient is missing all or part of a limb. In addition, there may be associated symptoms, such as phantom limb sensation, phantom pain, stump pain, and pain from the surgery itself.

Phantom limb sensation is the perception that the extremity is still present and occasionally distorted in position. Phantom limb sensation typically fades away within the first year after amputation, usually in a “telescoping” phenomenon. This includes the perception that the distal aspect of the limb (that is, the foot) is moving closer and closer to the site of amputation.

Phantom limb pain is differentiated as a painful perception within the absent body part. The incidence of phantom limb pain is variable and has been reported from 0.5% to virtually 100% of persons with amputations. This variability is due to differences in study methods and population. The most recent studies suggest that up to 85% of people with amputations will experience phantom pain [5]. Patients may describe the pain in the absent foot or the absent limb as cramping, stabbing, burning, or icy cold.

Pain at the surgical site is common and should resolve within a few weeks of surgery. Residual limb pain is perceived in the residual limb in the region of the amputation. The incidence of residual limb pain has been reported between 10% and 25%; it may be diffuse or focal and is commonly associated with neuroma, which is palpable around the amputation site.

Physical Examination

Wound healing, range of motion, muscle strength, and incisional integrity must be evaluated in the residual limb. Upper extremity strength should be assessed to determine capability for use of assistive devices.

Visualization of the contralateral foot is a mandatory component of the examination. The unaffected foot is assessed for areas of potential breakdown. These include the plantar surface of the foot, web spaces, and areas of bone prominence.

Skin breakdown in the residual limb is typically a result of pressure or shear forces in the healed limb. Skin necrosis may be evidence of ischemia with need for surgical revision. Skin breakdown can be manifested as abrasions from tape or the unraveling of an elastic wrap or be true partial- or full-thickness (pressure) sores. Pressure sore phenomenon typically occurs at bone prominences. The fibular head, hamstring tendons, patellar tendon, medial and lateral femoral condyles, and anterior distal tibia should routinely be examined for skin breakdown.

Joint contractures are a loss of full range of motion at a joint. They may be conceptualized as functional or mechanical. Functional contractures are the result of (inappropriate) positioning. A transtibial amputee may develop knee or hip flexion contractures merely by sitting with the hip flexed and the knee flexed at 90 degrees (the knee and hip extensors remain intact but are not being used). A mechanical contracture may result from unopposed muscle action. In the transfemoral amputee, the insertion of the hip adductors is sacrificed and the unopposed (and firmly attached) hip abductors may result in an abduction contracture.

The transtibial and Syme amputee requires evaluation of range of motion of the knee in flexion and extension. Medial and lateral knee stability must also be assessed. For successful ambulation with a prosthesis, knee extension muscle strength should be graded at least higher than 4/5. A knee flexion contracture of 10 degrees up to 18 degrees can usually be accommodated in a transtibial prosthesis; however, the absence of limb contractures is related to better success in prosthetic ambulation [6]. A contracture of more than 20 degrees requires that the individual ambulate with a bent socket, weight bearing through the knee.

In the transfemoral (above-knee) amputee, the range of motion evaluation should include hip flexion, hip extension, hip adduction, and hip abduction. A transfemoral prosthesis can functionally accommodate up to a 20-degree hip flexion contracture; a contracture of more than this makes prosthetic fitting and successful ambulation less likely. Strength should also be assessed, and grades of 4/5 or higher in muscles responsible for hip flexion-extension and abduction are required for ambulation.

Stump or residual limb pain is assessed first by inspection. Areas of obvious necrosis indicating poor blood flow may require surgical débridement. Nonhealing incisions are manifestations of ischemia, underlying hematoma, or abscess. The surrounding area should be palpated and assessed for induration and discharge. An attempt should be made to “milk” fluctuance, and drainage should be sent for Gram stain and culture. Sutures (if present) may need to be removed to facilitate evacuation of the abscess or hematoma. In some instances, the incision may need to be reopened for drainage and healing to take place.

Stump pain without signs or symptoms of infection should be evaluated for neuroma (palpation along the anatomic course of the sciatic nerve). Stump pain with or without skin breakdown may also be due to poor prosthetic fit, so the fit of the prosthesis ought to be evaluated, preferably with a prosthetist present. Nonblanchable erythema is a pressure sore until proved otherwise, and the prosthesis should not be worn until appropriate adjustments are made. Bruising at the distal aspect of the stump in the prosthetic wearer is indicative of a poor prosthetic fit. That is, the residual limb may be falling too deeply into the socket. Similarly, a choke phenomenon occurs with lack of total contact or inability to get the residual limb all the way into the socket. This can progress to verrucous hyperplasia, which predisposes the individual to fissuring and infection.

Gait evaluation with the prosthesis should be performed with an appropriate assistive device. Observed gait deviations should be communicated to the prosthetist for prosthesis modifications and to the therapist for focused gait training.

Functional Limitations

Functional limitations are largely dependent on the premorbid status of the individual. Ambulation with one limb or hopping (with a walker or crutches) requires approximately 60% increased energy over normal human locomotion. The energy cost of ambulation with a prosthesis varies. In the diabetic or dysvascular amputee, it approaches 38% to 60% increased energy for a below-knee amputee and 52% to 116% higher for an above-knee amputee [2,6]. An otherwise healthy person who has sustained a traumatic limb amputation or an individual who had been ambulating with crutches or another assistive device before having an amputation (often because of non–weight-bearing status on the affected limb) will probably be discharged from the acute care setting to home with outpatient services, at an “ambulatory” level with the appropriate assistive device; the energy expenditure will be less than that of a dysvascular amputee.

An older individual or person with multiple comorbidities should be encouraged to pursue functional independence by optimizing wheelchair mobility and transfers when there is inadequate cardiopulmonary reserve to ambulate with an assistive device [7]. This person may have had an acute or subacute rehabilitation hospital stay after the acute care hospitalization.

Functional limitations due to pain are associated with an inability to participate in ongoing activities of daily living. In general, symptoms of phantom sensation tend not to be an issue, whereas phantom pain can be severely limiting, preventing a person from participating in pre-prosthetic and prosthetic rehabilitation. Functional limitations related to stump or residual limb pain include the inability to tolerate stump shrinkage by appropriate modalities and an inability to tolerate gait training with a prosthesis. To accommodate stump pain, the patient may develop gait deviations to decrease pressure under the residual limb.

Individuals with significantly impaired cardiac output may not be able to perform pre-prosthetic training with a walker (or crutches). These patients may not be prosthetic candidates at all because of the increased energy demands of prosthetic ambulation [6]. Coronary artery calcification scores were very high in amputees compared with Framingham Risk Score–matched control groups. This suggested moderate to extensive coronary artery disease in more than two thirds of amputees studied. It may be relevant to carefully evaluate amputees for asymptomatic coronary artery disease and to consider prophylactic revascularization [8]. Keep in mind that individuals with preexisting amputations who undergo coronary artery bypass grafting will not be able to use an assistive device postoperatively (maintenance of sternal precautions), and alternative mobility options (e.g., power wheelchair) should be considered.

Rates of clinical depression range from 18% to 35% among amputees. Those with amputation-related pain are more prone to depression. Depression should be differentiated from the grief response and postoperative adjustment period [9].

Diagnostic Studies

The individual with phantom limb pain may benefit from diagnostic as well as therapeutic sympathetic nerve block. On occasion, electrodiagnostic tests (electromyography and nerve conduction studies) are helpful to differentiate symptoms of radiculopathy or other disease in the phantom limb.

In the younger amputee, it is occasionally necessary to obtain plain radiographs of the residual limb to assess the bone overgrowth. This is typically visually evident on inspection; the radiograph confirms the extent of overgrowth.

The individual with new amputation secondary to peripheral vascular disease may require cardiac evaluation to establish parameters for an exercise prescription.

Treatment

Initial

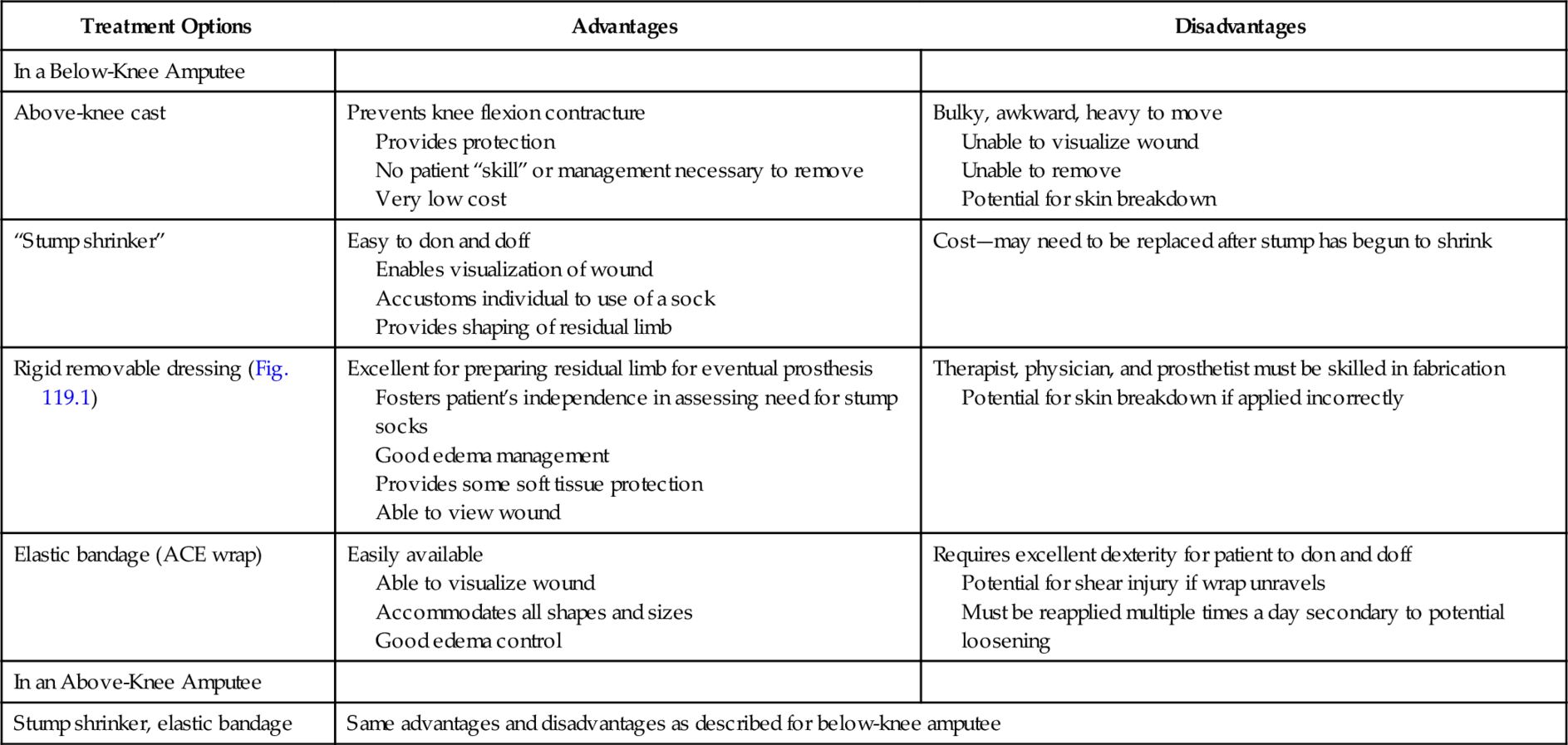

Initial treatment focuses on edema control and shaping of the residual limb as well as wound healing, prevention of contractures, and pain management. Options for edema control are listed in Table 119.1 [10,11].

Table 119.1

Treatment Options for Edema Control

| Treatment Options | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| In a Below-Knee Amputee | ||

| Above-knee cast | Prevents knee flexion contracture Provides protection No patient “skill” or management necessary to remove Very low cost |

Bulky, awkward, heavy to move Unable to visualize wound Unable to remove Potential for skin breakdown |

| “Stump shrinker” | Easy to don and doff Enables visualization of wound Accustoms individual to use of a sock Provides shaping of residual limb |

Cost—may need to be replaced after stump has begun to shrink |

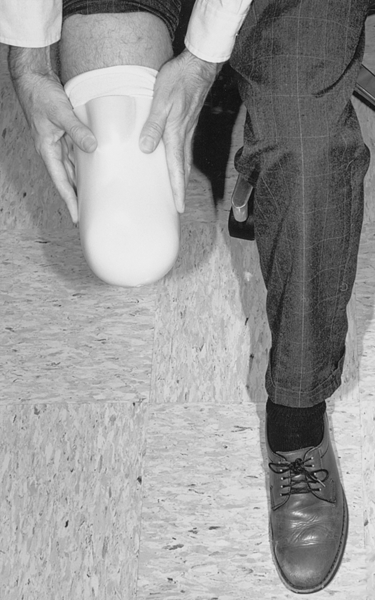

| Rigid removable dressing (Fig. 119.1) | Excellent for preparing residual limb for eventual prosthesis Fosters patient’s independence in assessing need for stump socks Good edema management Provides some soft tissue protection Able to view wound |

Therapist, physician, and prosthetist must be skilled in fabrication Potential for skin breakdown if applied incorrectly |

| Elastic bandage (ACE wrap) | Easily available Able to visualize wound Accommodates all shapes and sizes Good edema control |

Requires excellent dexterity for patient to don and doff Potential for shear injury if wrap unravels Must be reapplied multiple times a day secondary to potential loosening |

| In an Above-Knee Amputee | ||

| Stump shrinker, elastic bandage | Same advantages and disadvantages as described for below-knee amputee | |

Patients with a transtibial amputation have the potential for knee flexion and hip flexion contractures as a result of positioning (usually, sitting in a wheelchair or in bed). Therefore, avoidance of pillows under the knee and promotion of lying prone in bed can be helpful.

Persons with a transfemoral amputation may also develop hip flexion contractures as a result of sitting. In addition, there is the tendency for development of hip abduction contractures, so positioning of the hip in relative adduction, avoidance of pillows under the residual limb, and promotion of the prone position are essential.

Phantom sensation is not typically painful, although it can be frightening or disorienting for the patient. The best treatment is to reassure the patient that this is a normal reaction after amputation. Education and reassurance of the patient as well as ongoing tactile input (i.e., massaging the distal residual limb and using the limb) will enhance the accommodation to phantom sensation. There are many proposed treatments of phantom pain; however, there is no one definitive treatment that seems to work best. Initial pharmacologic intervention includes non-narcotic and narcotic analgesics; nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; anticonvulsants and membrane stabilizers, particularly gabapentin, duloxetine, and pregabalin; and tricyclic antidepressants [9].

Rehabilitation

Pre-prosthetic training focuses on functional independence in mobility and self-care from the ambulatory (single limb) or wheelchair level, avoidance of hip and knee contractures, and residual limb management. Prosthetic training is initiated once the residual limb is ready—the edema is resolved and the incision has healed; the prosthesis is then fabricated. A description of prostheses is beyond the scope of this chapter; however, the reader is referred to one of several texts on prosthetic components and prescription [12,13]. K levels are used by Medicare to determine an individual’s functional potential and thus to justify prosthetic components (Table 119.2). When the prosthesis has been fabricated, an outpatient appointment with the ordering physician is scheduled that is attended by the patient and the prosthetist. A basic evaluation of the fit of the prosthesis is conducted, and referral for physical therapy that focuses on prosthetic training is made at that time, or adjustments to the prosthesis are made. The patient must be taught how to put on (don) and take off (doff) the prosthesis as well as when to add socks for a better fit. The patient should also be encouraged to routinely inspect the skin on the residual limb (often done best with a long-handled mirror).

Table 119.2

K Levels

| K0 (level 0) | Does not have the ability or potential to ambulate or to transfer safely with or without assistance, and a prosthesis does not enhance the quality of life or mobility |

| K1 (level 1) | Has the ability or potential to use a prosthesis for transfers or ambulation on level surfaces at fixed cadence—typical of the limited and unlimited household walker |

| K2 (level 2) | Has the ability or potential for ambulation with the ability to traverse low-level environmental barriers, such as curbs, stairs, or uneven surfaces—typical of the limited community walker |

| K3 (level 3) | Has the ability or potential for walking with variable cadence—typical of the community walker who is able to traverse most environmental barriers and may have vocational, therapeutic, or exercise activity that demands prosthetic use beyond simple walking |

| K4 (level 4) | Has the ability or potential for prosthetic use that exceeds basic walking skills, exhibiting high impact, stress, or energy levels—typical of the prosthetic demands of the child, active adult, or athlete |

Occupational therapy consists of identifying necessary equipment (e.g., toilet safety frame, tub transfer bench) and establishing independence in self-care from the wheelchair or ambulatory level with use of just the unaffected limb (single-limb stance). Occupational therapy should also be ordered when the patient receives the prosthesis to establish independence in self-care, particularly with lower extremity dressing, toileting, and homemaking while the prosthesis is worn.

Return to driving is an important aspect of functional independence. The majority (80.5%) of prosthetic users with major lower extremity amputations are able to return to automobile driving 3.8 months after amputation. People with left-sided amputations have significantly fewer concerns about driving; those with right-sided amputations may need vehicle modifications (40%) or may need to switch to left-foot driving style [14].

Procedures

Treatment of postamputation phantom pain includes sympathetic blocks, which are typically performed under fluoroscopic guidance. Neuromas, which typically form 1 to 12 months after amputation, may be manifested as a focal soft tissue mass with reproducible pain on palpation. Local anesthetic injection may provide pain relief. Surgical resection is an option but can result in a new (painful) neuroma [15].

Surgery

Surgery is indicated when a residual limb requires wound revision or higher level of amputation. Hamstring releases have a limited role or no role because they would inhibit the ability to walk. There does not appear to be any role for surgical stump revision for treatment of phantom pain.

There are few data to promote dorsal root entry zone ablation, dorsal rhizotomy, dorsal column tractotomy, thalamotomy, or cortical resection in the treatment of phantom pain. A small trial to surgically treat phantom pain locally was performed. The sciatic nerve was split proximal to the popliteal fossa, and the two parts were reconnected in a sling fashion. Of 15 patients, 14 reported that the procedure was “very helpful.” [15]

Bone overgrowth develops in 10% to 30% of children with congenital amputations, and this must be addressed surgically. This is much less common in the adult with an acquired amputation.

Potential Disease Complications

The most common complications are dehiscence or breakdown of the incision and nonhealing wounds. Infection or ischemia is the most likely cause of dehiscence or a nonhealing incision. A trial of conservative management including antibiotics (after a culture specimen is obtained) and appropriate local wound care is reasonable. Increasing wound necrosis, foul drainage, and fever or chills warrant reevaluation by the surgeon.

Other potential complications may involve cardiac ischemia as a heretofore inactive (i.e., energy conservative) individual begins using up to 100% more energy for gait training [6]. A reasonable guideline for gait training is assessment of an individual’s ability to ambulate with the intact lower extremity with crutches or another assistive device. This consumes approximately 60% more energy than bipedal human locomotion. A person who is not able to gait train (hop on one foot short distances) with use of an assistive device is probably not a potential prosthetic ambulator. Major limb amputation continues to result in significant morbidity and mortality. One-year survival for dysvascular and diabetic individuals is 50.6% for transfemoral amputees and 74.5% for transtibial amputees. Five-year survival is 22.5% and 37.8% (survival in end-stage renal disease is as low as 14% at 5 years after amputation) [2,3].

Potential Treatment Complications

Once the prosthesis has been fabricated, skin breakdown is the most common complication. Breakdown commonly occurs at the distal anterior tibia (clapper-in-bell phenomenon, a result of continued forward motion of the distal residual limb in the socket during swing phase), the hamstring tendons (tight brim), and the patellar tendon.

Patients should be instructed to inspect these areas and immediately report to the prosthetist signs of persistent, nonblanchable erythema. The prosthesis should not be worn until modifications are made.

Medication side effects depend on the particular medication being used as well as potential for drug interactions when multiple medications are being used.