CHAPTER 117

Trigeminal Neuralgia

Josemaria Paterno, MD; Aneesh Singla, MD, MPH

Definition

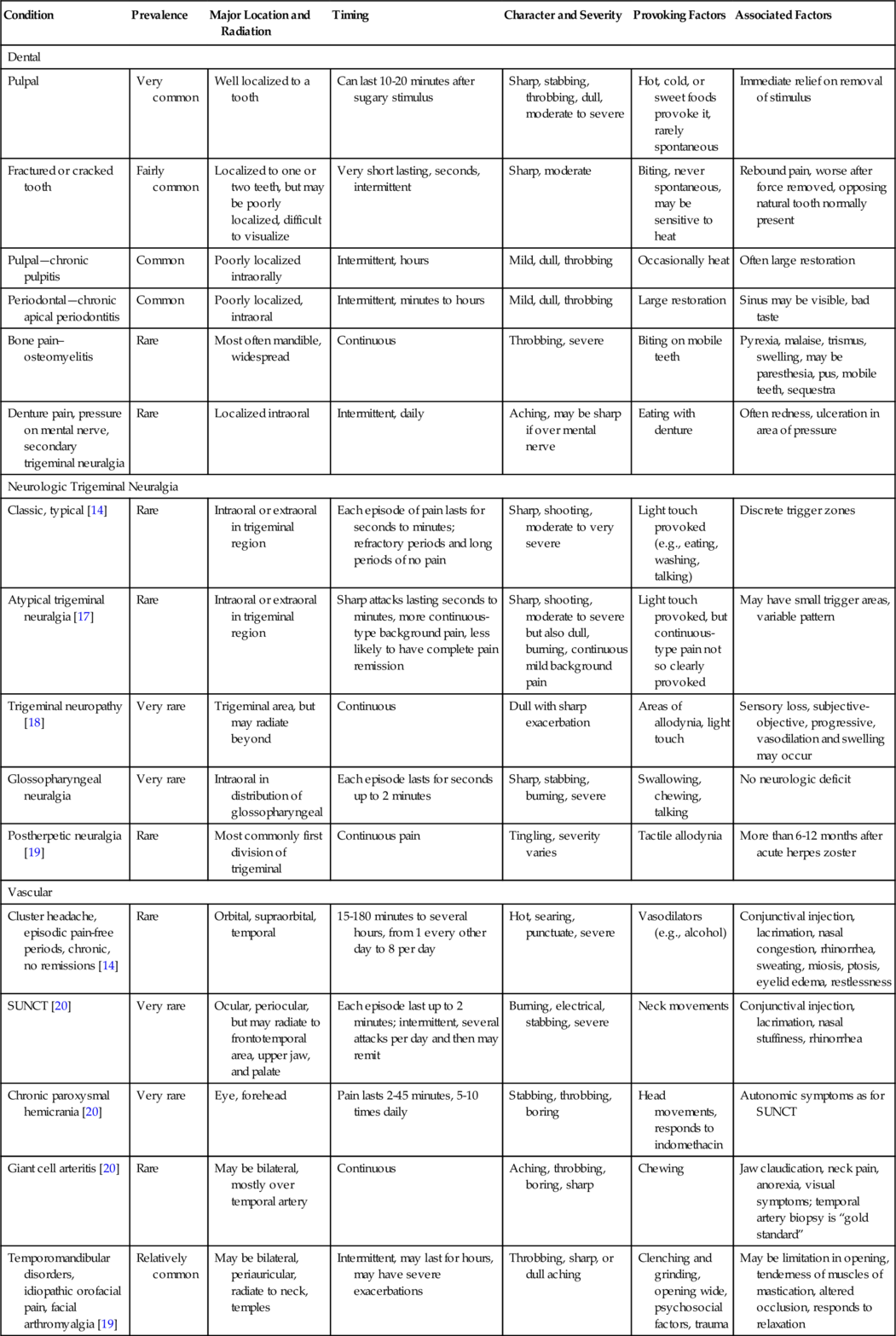

Trigeminal neuralgia is pain in the distribution of the trigeminal dermatomes. The pain is described as an electric shock–like, stabbing, unilateral pain having abrupt onset and termination. Intervals between attacks are pain free. Non-noxious triggers occur in the same or different sensory areas of the face, and there is minimal or no sensory loss in the region of pain [1–7]. Trigeminal neuralgia has an incidence of 4 or 5 per 100,000 people up to 20 per 100,000 per year after the age of 60 years [7–9] and a prevalence of 0.1 to 0.2 per 1000. The female-to-male ratio is about 3:2 [8].

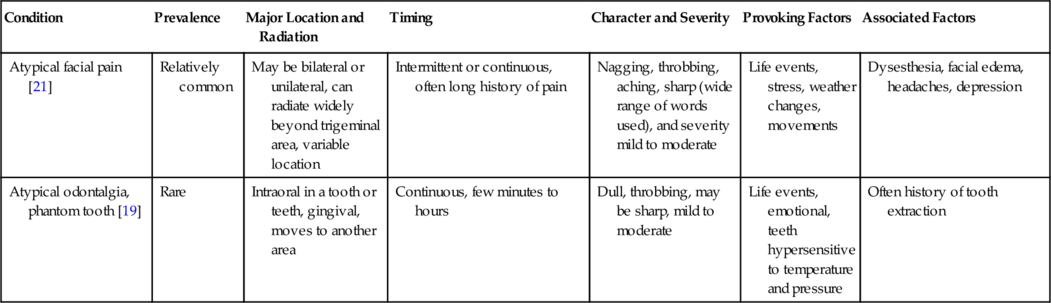

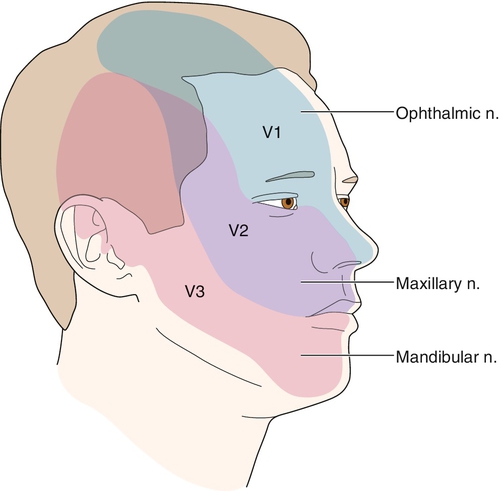

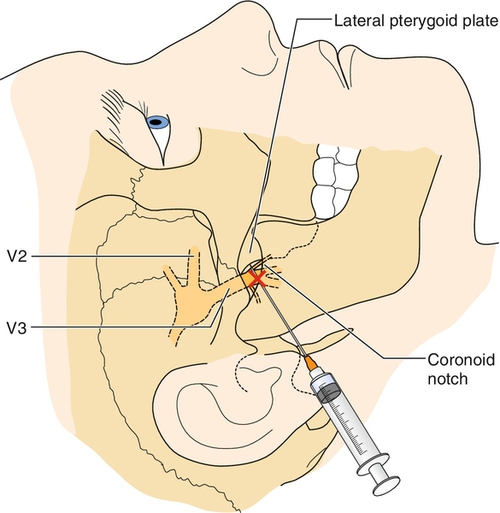

The trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V) is the largest of the cranial nerves. It begins in the brainstem at the trigeminal nucleus and travels along the ventrolateral surface of the pons and through the subarachnoid space until it enters the temporal bone, where it forms into the gasserian ganglion located in the Meckel cave [10]. The divisions are the ophthalmic or V1 branch, the maxillary or V2 branch, and the mandibular or V3 branch (Figs. 117.1 and 117.2). The relative distribution of pain in trigeminal neuralgia is as follows: V1, 20%; V2, 44%; V3, 36% [10].

Most patients with classic symptoms have mechanical compression of the trigeminal nerve as it leaves the pons and travels in the subarachnoid space toward the Meckel cave [10–12]. Most commonly, there is cross-compression by a major vessel. Other proposed causes include demyelinating plaques from multiple sclerosis, neoplastic disease, and abscess formation with bone resorption and irritation of the trigeminal nerve in the maxilla or mandible. Trigeminal neuralgia occurs in about 1% of patients with multiple sclerosis, and approximately 2% to 8% of patients with trigeminal neuralgia have multiple sclerosis [7,8,13].

Regardless of the etiology, it is likely that both peripheral and central mechanisms play a role in the pathogenesis of this syndrome.

Symptoms

Typical trigeminal neuralgia symptoms involve electric shock–like pain in the distribution of one or more branches of the trigeminal nerve. Pain is often intermittent, with pain-free intervals of months or even years [10]. The pain may last a few seconds to less than 2 minutes. The pain has at least four of the following five characteristics: distribution along one or more divisions of the trigeminal nerve; sudden intense, sharp, superficial, stabbing, or burning quality; severe intensity; precipitation from trigger areas or by certain daily activities, such as eating, talking, washing the face, or cleaning the teeth; and between paroxysms, the patient is completely asymptomatic [6,14]. In general, patients do not report any other neurologic deficit.

Physical Examination

The diagnosis of trigeminal neuralgia is made primarily by history. The Sweet criteria for this diagnosis are five pain descriptors. The diagnosis must be questioned if these criteria are not met [5], as follows: the pain is paroxysmal; the pain may be provoked by light touch to the face (trigger zones); the pain is confined to the trigeminal distribution; the pain is unilateral; and the findings on clinical sensory examination are normal [5,15]. When possible, physical examination of the oral cavity, dentition, and trigeminal nerve distribution should be performed to rule out other diseases. A complete cranial nerve examination should be performed. In general, no sensory or motor deficits are present, but serial examinations may detect a change and identify a secondary cause of trigeminal neuralgia [6].

Functional Limitations

In general, there are no impairments associated with trigeminal neuralgia. However, the pain from this entity may result in significant limitation in several activities of daily living. During exacerbations, patients may be functionally incapacitated because of pain and may be unable to perform activities such as comb hair, chew food, or shave. Talking on the telephone may be painful. Wearing glasses or makeup may not be possible. The pain from trigeminal neuralgia is not continuous but paroxysmal, suggesting spontaneous discharges from specific neurons, and it frequently occurs by innocuous tactile stimuli [4]. Therefore any activity that involves contact with the face may become difficult or impossible.

Diagnostic Studies

When a diagnosis of trigeminal neuralgia is suspected, patients should have diagnostic brain imaging with magnetic resonance imaging. Magnetic resonance imaging with gadolinium contrast can aid in diagnosis of multiple sclerosis plaques, neoplasm, and any neurovascular compressive relationship to the trigeminal root [5]. Electromyography, nerve conduction studies, and quantitative sensory testing may provide sensitive, quantitative, and objective results for the diagnosis, localization, and accuracy of damage to the trigeminal nerve [16]. Other studies that may have a role in diagnosis include intraoral, skull, and sinus radiographs and daily diaries of pain.

Treatment

Initial

Treatments that may help with trigeminal neuralgia include heat or cold therapy, massage, avoidance of triggers, and application of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation [8,9]. Topical ointments such as lidocaine, ketamine, and ketoprofen may help as well [8,9]. Pharmacologic options are listed in Table 117.2. The anticonvulsant carbamazepine is considered a first-line therapy and has been efficacious in several controlled trials [22–25]. Carbamazepine can be associated with systemic issues affecting the hematologic and endocrine system (see “Potential Treatment Complications”). The carbamazepine derivative oxcarbazepine is associated with fewer side effects and often better tolerated. Baclofen and lamotrigine have also been helpful in controlled trials [22,26,27]. Uncontrolled observations, clinical practice, and the authors’ experience also suggest that phenytoin, clonazepam, topiramate, sodium valproate, gabapentin, pregabalin, zonisamide, levetiracetam, mexiletine, and lidocaine may be useful [22]. Pharmacologic therapy with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, acetaminophen, tricyclic antidepressants, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, and muscle relaxants may be useful. One study showed that intranasal lidocaine 8% administered by a metered-dose spray produced prompt but temporary analgesia without serious adverse reactions in patients with second-division trigeminal neuralgia [28]. In general, 80% of patients will respond to medical therapy [7].

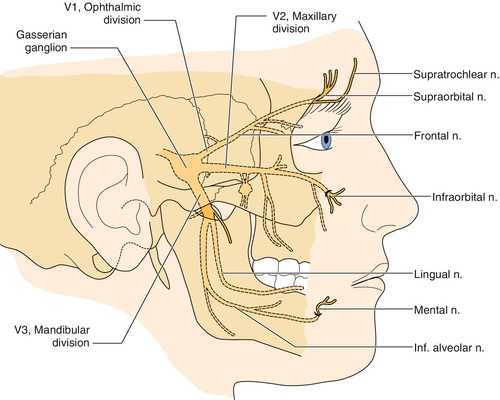

Table 117.2

Pharmacologic Options for Trigeminal Neuralgia Reported in the Literature

| Drug | Daily Dose | NNT |

| *Carbamazepine | 300-2400 mg | 1.4-2.1 (1.1-3.9) |

| *Baclofen | 60-80 mg | 1.4 (1.0-2.6) |

| *Lamotrigine | 400 mg | 2.1 (1.3-6.1) |

| Phenytoin | 300-400 mg | |

| Clonazepam | 6-8 mg | |

| Valproate | 1200 mg | |

| Oxcarbazepine | 1200-1400 mg | |

| Gabapentin | 600-2000 mg | |

| Intravenous lidocaine | 2-5 mg/kg | |

| Mexiletine | 10 mg/kg |

From Sindrup SH, Jensen TS. Pharmacotherapy of trigeminal neuralgia. Clin J Pain 2002;18:22-27.

NNT is number needed to treat to obtain 1 patient with at least 50% pain relief.

* Indicates data from placebo-controlled trials.

Rehabilitation

Modalities for pain control, such as electrical stimulation, ice massage, and hot packs, can play a role in rehabilitation and recovery from trigeminal neuralgia. Speech therapy may be indicated to help with oral motor deficits that affect speech or swallowing.

Adaptive equipment, such as a telephone earset, may be recommended. Some general chronic pain rehabilitation approaches may also be useful, such as improved sleep hygiene, low-intensity aerobic exercise, biofeedback, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and relaxation techniques. Acupuncture may also have a role in the management of trigeminal neuralgia [29]. After surgical intervention with microvascular decompression, the rehabilitation process is often brief. Trigeminal neuralgia pain relief is usually immediate, and neuropathic medications are gradually discontinued in the weeks after surgery. If pain does recur, medications may be restarted, or if necessary, a second interventional procedure may eventually be needed.

Trigeminal neuralgia patients with underlying multiple sclerosis face many therapeutic challenges. Rehabilitation exercises that improve multiple sclerosis symptoms and quality of life can help modulate the impact of trigeminal neuralgia. Aerobic exercise has been shown to improve quality of life, pain, fitness, and function in multiple sclerosis patients with moderate to severe disability [30].

Procedures

With medically refractory trigeminal neuralgia, physicians and patients can choose among several interventions, such as transient nerve blocks, rhizotomy by radiofrequency (RF) ablation, stereotactic radiosurgery, and surgical microvascular decompression. Local anesthetic trigeminal nerve blocks may reduce the intensity or the episodes of pain (Fig. 117.3), but the pain often outlasts the duration of the local anesthetic. Nerve blocks can be repeated at intervals but are more useful as a diagnostic test to judge candidacy for percutaneous RF ablation [3]. RF ablation is the most common nonsurgical intervention performed for trigeminal neuralgia, with a reported initial success rate of more than 90% [31–33]. However long-term efficacy of RF ablation is lower than that of microvascular decompression, with approximately 20% reporting recurrence of pain within 12 months [31,32,34]. In a review of 1600 RF ablations of the trigeminal nerve, Kanopolat reported the most common side effects to be weakened corneal reflex (5.7%), masseter weakness (4.1%), and dysesthesia (1%) [31]. Regarding specific RF technique, conventional RF was clearly more efficacious than pulsed RF in a double-blind randomized trial of 40 patients with idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia [34].

Stereotactic radiosurgery is another option for trigeminal neuralgia. A focused beam of radiation is used to target the trigeminal nerve root. Success rates of 80% have been reported, but microvascular decompression still offers superior long-term outcomes [33,35,36]. However, both RF ablation and stereotactic radiosurgery are viable alternatives to microvascular decompression, especially for high-risk elderly patients, the patient’s preference to avoid surgery, or prior failed microvascular decompression.

Other forms of rhizotomy have reported good short-term results with neurolytic agents such as alcohol and glycerol. The consensus among most physicians is that these particular techniques have lower success rates and higher morbidity [3].

Surgery

Overall nonsurgical interventions are effective but lack robust long-term efficacy, leading to repeated interventions. Definitive surgical therapy is microvascular decompression, which entails a craniotomy to insert a felt barrier or inert sponge between the compressing vessel and trigeminal nerve origin in the cerebellopontine angle cistern. Overall long-term outcomes are excellent, with complete pain relief as high as 70% to 86% several years after surgery [37–39]. Although the elderly have traditionally been considered a higher risk group for microvascular decompression, more recent data from small prospective studies indicate that some older patients can safely undergo microvascular decompression [38,39].

Furthermore, although it is still experimental, intracranial neurostimulation provides an alternative means for trigeminal neuralgia pain relief in surgically and medically refractory cases. By implantation of electrodes to the facial motor cortex, motor cortex stimulation has shown efficacy for neuropathic facial pain. Motor cortex stimulation has shown particular promise in the treatment of trigeminal neuropathic pain and central pain syndromes, such as thalamic pain syndrome [40].

Potential Disease Complications

Trigeminal neuralgia is generally amenable to surgical treatment or pharmacotherapy. However, it can progress to become a chronic intractable pain syndrome. In refractory cases, it is important to consider other diagnoses or facial pain syndromes.

Potential Treatment Complications

Carbamazepine can be associated with numerous side effects, including aplastic anemia and the syndrome of inappropriate diuretic hormone secretion; hence, frequent monitoring is necessary. Our practice is to check a CBC and chemistry panel 2 weeks after starting the medication, monthly for 3 months, and then every 6 to 9 months thereafter. If the patient is on a stable dose and a dose adjustment is made, we recheck the labs within 1 month after the dose change. For Gamma Knife radiosurgery, post-treatment facial numbness was reported as bothersome in 5%, commonly in patients who underwent another invasive treatment [36]. Although microvascular decompression has the best efficacy and durability of all treatments, known complications can be serious and include up to a 4% risk of cerebellar hematoma, cranial nerve injury, cerebrospinal fluid leak, stroke, and death—complications not seen with the less invasive ablative procedures [41]. In addition, in a case series of 67 elderly patients undergoing posterior fossa exploration for trigeminal neuralgia, complications occurred in 10 patients (15%) and included ataxia (10%), hearing loss (5%), trigeminal dysesthesias (5%), facial weakness (3%), aseptic meningitis (2%), and pulmonary embolus (2%) [39].