CHAPTER 116

Tietze Syndrome

Marta Imamura, MD; Satiko T. Imamura, MD

Definition

Tietze syndrome is a benign, self-limited, nonsuppurative localized painful swelling of the upper costal cartilages of unknown etiology [1–10]. It affects the costochondral, costosternal, or sternoclavicular joints [2,5–7,9]. The manubriosternal and xiphisternal joints are less frequently affected [5,10]. First described in 1921 by a German surgeon in Breslau, Alexander Tietze, it is different from the costosternal syndrome [5–12]. Tietze syndrome is a rare cause of benign anterior chest wall pain associated with local swelling of the involved costal cartilages (Fig. 116.1) [5,6,12]. It is typically described in young adults and is a disease of the second and third decades of life [10,12]. Although it is not common, Tietze syndrome may also appear in children, infants [10,13], and elderly people [14]. It affects both men and women in a 1:1 ratio [4–6,9,10,15]. Lesions are unilateral and single in more than 80% of patients [4,10], and the second and third costal cartilages are most commonly involved [1,4,6,9–12]. Costosternal syndrome, a frequent cause of benign anterior chest wall pain, is not associated with a local swelling of the involved costal cartilages [5–12]. Costosternal syndrome usually occurs during and after the fourth decade of life, more frequently in women in a rate of 2 to 3:1 [9,10]. Multiple costal cartilages are involved in 90% of patients with costosternal syndrome [5,9,10].

The pathogenesis of Tietze syndrome is unknown [1–4,6, 8–10]. Recurrent functional overloading or microtrauma to the costal cartilages from severe coughing, heavy manual work, and sudden movement of the rib cage as well as malnutrition, sprain of the intra-articular sternocostal ligament, and respiratory tract infections may influence the development of Tietze syndrome [2,5,6,8–10,12,15]. Costal swelling may be due to focal enlargement [4,7], ventral angulation or irregular calcification of the affected costal cartilage [4,16], and thickening of overlying muscle [16,17]. Tietze syndrome may mimic a variety of life-threatening clinical entities [4,6,15] and must be considered in the differential diagnosis of any painful mass in the peristernal area. Clinical awareness of this syndrome and of its benign course may minimize performance of invasive diagnostic procedures [13].

Symptoms

Clinical manifestations include the sudden or gradual onset of pain of variable intensity [3,4,10,15] in the upper anterior chest wall in association with a fusiform and tender swelling of the involved costal cartilage [4,15]. Despite descriptions that pain may radiate to the shoulder, arm, and neck [3,4,12], its distribution usually occurs within the segment innervated by the afferent fibers carrying the painful impulse [2]. It is often aggravated by motion of the thoracic wall, sneezing, coughing, deep breathing, bending, exertion [1–8,15], and lying prone or over the affected side [10]. Some patients report inability to find a comfortable position in bed and have pain on turning over in the bed [1]. Weather change, anxiety, worry, and fatigue may exacerbate the pain [4]. Symptoms are usually unilateral, with no preferential side [3]. There is no reported association with sternotomy.

Physical Examination

On physical examination, a slight firm swelling is noted at the involved site [1–4,15]. Systemic manifestations [4,6,10,13,15] and inflammation are usually absent [1,4,5,7,10,15], but there may be local heat [15]. Pain is reproduced with active protraction or retraction of the shoulder, deep inspiration, and elevation of the arm [12] (Fig. 116.2). A unique visible, spherical, nonsuppurative, tender tumor of elastic-hard and pasty consistency can be palpated, usually over the second and third costochondral joints. Local palpation with firm pressure over the localized tender swelling reproduces the spontaneous pain complaint [12] (Fig. 116.3). Physical examination findings of the musculoskeletal and neurologic systems of reported cases from the literature are usually normal except for the local findings [4–6,13,15,17]. Muscle strength and upper limb range of motion may be decreased because of pain. Dermatomal and subcutaneous hyperalgesia (Fig. 116.4) and hyperemia (Fig. 116.5) may be present in the involved thoracic spinal segments. The adjacent intercostal [12], sternal, and pectoralis major and minor muscles may be tender to palpation [14].

Functional Limitations

The disability produced by Tietze syndrome is usually minor, although it can be severe with activity restriction involving the trunk and upper limbs. Activities such as lifting, bathing, ironing, combing and brushing hair, and other activities of daily living can be problematic. Patients who have physically vigorous jobs may need to be put on light duty for weeks and avoid physical efforts of the upper limbs and trunk [1]. Functional limitations may also be due to chronic pain [18]; however, even of those patients who continue to have pain after 1 year, most lead a life without disability.

Diagnostic Studies

Diagnosis of Tietze syndrome is essentially made on a clinical basis: anterior chest wall pain confirmed by palpation of a tender swelling at the second or third costochondral junction that reproduces the patient’s complaint in the absence of another definite diagnosis [3–5,7–9,11,15]. Results of laboratory analysis including inflammatory and immunologic parameters are usually normal [4–9,15]. Some cases may show a slight increase in the erythrocyte sedimentation rate [7,13,15].

Chest, rib, and sternum plain films and conventional tomograms of the costochondral junction are generally normal [6,17,19]. Plain radiographs may show cartilage enlargement on tangential views, chondral calcification, irregularities at the joint surface, osteosclerosis, and presence of osteophytes at the costal joint. However, these radiographic changes may also be found in physiologic costochondral calcifications [20]. Plain radiographs are therefore mainly indicated to rule out occult bone diseases including tumors, low-grade infections, tender fat or lipomas, chest wall contusion, and congenital deformity [4,12,16]. Tuberculosis, chondroma, and chondrosarcoma are mostly located at the costochondral junction [16].

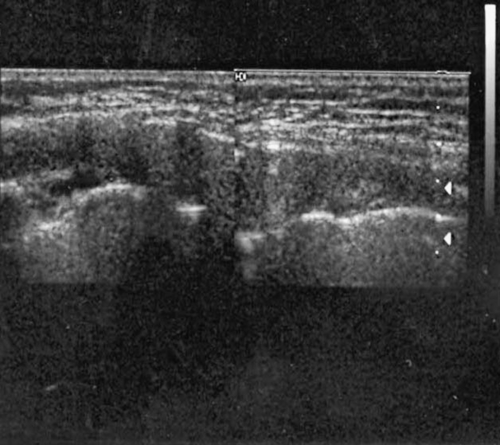

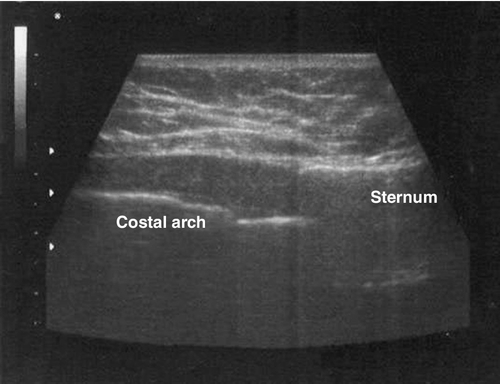

Ultrasonographic findings of the affected costochondral joints are characterized by an increase of the size of the affected costal cartilage compared with the contralateral symmetric joint and normal age- and gender-matched controls (Fig. 116.6) [21]. There is also a nonhomogeneous increase in the echogenicity in the diseased cartilage, with dotty, hyperreflective echoes and intense broad posterior acoustic shadow [21]. The normal ultrasonographic picture of the costal cartilage (Fig. 116.7) is manifested as a hypoechoic oval area with the absence of posterior acoustic shadows in the longitudinal scans [21], and it appears as a ribbon-shaped homogeneous hypoechogenicity in the transverse scan with no posterior acoustic shadowing [21].

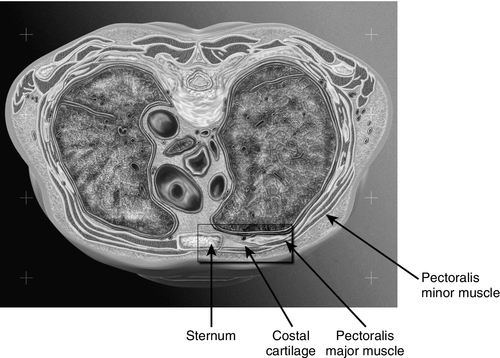

Computed tomography of the chest is an effective noninvasive means of imaging costal cartilage and adjacent structures in patients with Tietze syndrome [17,19,21]. Costal cartilage is normally symmetric in size and orientation at any level and is normally oriented along the horizontal axis [17]. Cartilage density is uniform and greater than that of the overlying muscle but less than calcium density [17]. Reported computed tomographic abnormalities of patients with Tietze syndrome include focal enlargement of the involved costal cartilage [6,17,19], ventral angulations [6,15,17,19], swelling or irregular calcification of the affected costal cartilage [17,19], perichondral soft tissue swelling, and periarticular bone sclerosis [5,22]. Computed tomography scan is useful to exclude other possible causes of chest wall or thoracic mass [6], such as malignant lymphoma [17,23] and mediastinal carcinoma [24]. Fluorodeoxyglucose–positron emission tomography can also be used in the differential diagnosis with malignant neoplasms [25].

Asymmetric thickening of the pectoralis major muscle simulating a chest wall mass can also be excluded [17]. Planar bone scanning with technetium Tc 99 usually reveals intense tracer uptake, but the findings are not specific [4,6,15,20,22]. Bone scintigraphy allows the precise localization of the involved joint [6] and the delineation of the number of involved joints; it should be considered to rule out occult fractures of the ribs and sternum in cases of local trauma [12].

Pinhole skeletal scintigraphy seems to enhance diagnostic specificity [20]. It is able to show a characteristic appearance of a drumstick-like pattern in acute cases and a C- or inverted C–shaped uptake in the chronically affected costal cartilage [20].

Magnetic resonance imaging of the costosternal and sternoclavicular joints usually shows thickening at the site of complaint; focal or widespread increased signal intensities of affected cartilage on both T2-weighted and short T1 inversion recovery or fat-saturated images; bone marrow edema in the subchondral bone; and intense gadolinium uptake in the areas of thickened cartilage, in the subchondral bone marrow, or in capsule and ligaments [26]. Magnetic resonance imaging is also indicated if an occult mass is suspected [9,12]. Magnetic resonance imaging allows differentiation of cartilage and bone abnormalities [26].

The histopathologic characteristics of costal cartilage in Tietze syndrome are usually normal [15] or nonspecific [3,6,7,15]. These characteristics include increased vascularity and degenerative changes with patchy loss of ground substance leading to a fibrillar appearance [6,22,27]. Degenerative changes occur with the formation of clefts, which may undergo calcification [1,22,27].

Treatment

Initial

Treatment is symptomatic because the pathogenesis of the disease is still unclear [3,4,6,14,15]. The natural history of patients diagnosed with true Tietze syndrome is, in general, good and benign because of the self-limited characteristic of the condition. In the majority of cases, pain disappears spontaneously within a few weeks and swelling in a few months [15] without treatment [9]. Symptoms may be exacerbated after manual work and severe cough. During this period, the use of an elastic rib belt may also provide symptomatic relief and help protect the costosternal joints from additional trauma [9,12]. Initial treatment of the pain and functional disability associated with Tietze syndrome should include simple oral analgesics such as acetaminophen, oral or topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) alone [6,9,11,14] or in combination with codeine [5,8,9,15], or tramadol. Reassurance about the benign nature of the disorder and the diagnosis of a non–life-threatening but real and well-recognized musculoskeletal pain disease can often by itself reduce the anxiety and fears and lead to symptomatic pain relief [2–5,8–11,15,29]. Avoidance of iatrogenic worries is usually helpful [29]. Removal of aggravating and perpetuating factors (including physical efforts of the upper limbs and trunk, chronic cough, and bronchospasm) and improved nutrition are also important [1,5,8,9,14]. Human calcitonin at the dosage of 0.25 mg/day was given for a course of 1 month to five women diagnosed with Tietze syndrome who had intense pain not relieved by conventional treatment [30]. Three patients reported complete remission of symptoms and imaging findings, and symptoms improved in two patients with disappearance of pain [30].

Rehabilitation

Physical modalities including local superficial heat for 20 minutes, two or three times a day, and ice for 10 to 15 minutes, three or four times a day, can be performed until symptoms are improved [3,12,14]. Heat and cold are equally effective, and the choice of modality relies on the patient’s preference and tolerance. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation and electroacupuncture may be applied over the painful area [14]. Electroacupuncture is applied by introducing the acupuncture disposable needle over the skin points of lower electrical skin resistance [14] that are located within the involved spinal segments. Galvanic or faradic low-frequency electrical currents are applied at the inserted needle [14]. Administration of corticosteroids by iontophoresis may provide more prolonged pain relief [11]. Gentle, pain-free range of motion exercises should be introduced as soon as tolerated [12]. Vigorous exercises should be avoided if they exacerbate the patient’s symptoms [12]. Proper posture during sitting or working activities should be restored [5,8,9]. Inactivation of associated pectoralis major trigger points followed by relaxation and stretching exercises with relaxation of the involved muscles may also be helpful. Stretching exercises of the pectoralis major muscle, such as the standing pushup in the corner for 10 seconds, repeated for 1 or 2 minutes several times a day, may be helpful [8,31]. Vapocoolant spray applied to the involved areas may also relieve chest wall pain [8]. Patients should be instructed to avoid improper posture or repetitive misuse of chest wall muscles [8].

Psychological and psychopharmacologic treatment should be considered for patients with continuing symptoms and disability, especially if these are associated with abnormal health beliefs, depressed mood, panic attacks, or other symptoms such as fatigue or palpitations [29]. Both cognitive-behavioral therapy and selective reuptake inhibitors have been shown to be effective [29]. Tricyclic antidepressants are helpful in reducing reports of pain in patients with chest pain and normal coronary arteries [29].

Procedures

Most patients respond to NSAIDs, heat, and activity modification. For patients who do not respond to the initial and rehabilitation treatment modalities, however, a local anesthetic [2,4,6] and steroid injection can be performed as the next symptom control maneuver [2,5,6,8,9,11,12,15,21]. Injection of the costal cartilage is performed by placing the patient in the supine position [12,21]. Proper preparation with antiseptic solution of the skin overlying the affected costal cartilage is carried out with isopropyl alcohol and soluble iodine solution to swab the injection site [21]. The exact position for injection is identified by clinical and ultrasonographic examination [21]. The injection site is the point of maximum tenderness by palpation or the point of maximum cartilaginous hypertrophy by ultrasonographic examination [21]. A refrigerant spray may be used to anesthetize the overlying skin before the needle is inserted [21]. There should be limited resistance to injection [12]. If significant resistance is found, the needle should be withdrawn slightly and repositioned until the injection proceeds with only limited resistance [12]. This procedure should be repeated for each affected joint [12]. After the needle is removed, a sterile pressure dressing and ice pack are placed at the injection site [12]. Local steroid injections associated with local anesthetics have shown good therapeutic results [21]. There is an average of 82% decrease in the size of the affected costal cartilage 1 week after the local anesthetic and steroid injection, and the posterior acoustic shadowing is absent [21]. Clinical examination of the injected patients detected complete resolution and substantial improvement of signs and symptoms of pain and swelling. This shows a strong correlation between clinical changes and ultrasonographic findings in patients with Tietze syndrome. An intercostal nerve block performed 1.5 to 2 inches proximal to the costochondral joint of the affected level provides even longer lasting pain relief and is indicated if other measures are not effective [11].

Surgery

Surgical procedures are rarely necessary and indicated only if the symptomatic conservative measures failed to alleviate symptoms [9]. Surgical excision of the localized involved cartilage can be performed in severe and refractory cases [9]. Costosternal or sternoclavicular arthrodesis may be performed if conservative measures fail to provide satisfactory results.

Potential Disease Complications

Tietze syndrome is a benign condition and rarely presents complications. It is self-limited with spontaneous recovery of the pain after a few weeks or several months [1,3,4,15] to 1 year in the majority of cases. Swelling may persist for months [15] to years [4]. The course of this condition is characterized by periods of recurrence and improvement [1,3,4,14].

Potential Treatment Complications

The systemic complications of NSAIDs are well known and most commonly affect the gastric, hepatic, and renal systems. The major complication of the local steroid combined with local anesthetic injections is pneumothorax if the needle is placed too laterally or deeply and invades the pleural space [12]. Cardiac tamponade as well as an iatrogenic infection, although rare, can occur if, respectively, the needle is placed in the direction of the heart and strict aseptic techniques are not performed [12]. The possibility of trauma to the contents of the mediastinum remains another possibility [12]. This complication can be greatly decreased if the clinician pays close attention to accurate needle placement [12] or performs the injection with ultrasound guidance [21].