CHAPTER 113

Temporomandibular Joint Dysfunction

Steven Scott, DO; Robert Kent, DO, MHA, MPH; Julie Martin, PT; Marissa McCarthy, MD; Jill Massengale, MS, ARNP; Tony Urbisci, BS

Definition

The temporomandibular joint (TMJ) is the synovial articulation between the mandible and the cranium. The TMJ is unusual in that the articular surfaces are covered by fibrous tissue rather than hyaline cartilage, as in most joints, and that it is divided into two joint spaces by an intra-articular disc. TMJ dysfunction (TMD) includes a collection of symptoms that refer to intrinsic and extrinsic TMJ conditions. These conditions are commonly referred to as TMJ, although they should more accurately be referred to as TMD to specify a difference between the joint itself and a true dysfunction. These symptoms include issues that cause pain or dysfunction relating to the TMJ itself as well as to the muscles of mastication. Because of the high number of issues that can be manifested in the facial and temporal area, a thorough history and physical examination are necessary to identify the true cause of pain in this area.

Studies report that approximately 28% of the population exhibits signs of TMD. Of those people suffering from symptoms, 14% had actual restricted range of motion of the mandible [1]. There is historically a predominance in women (5:1 versus men), and it occurs most often in patients between the ages of 15 and 45 years [2–4]. The most common cause of TMD is myofascial pain dysfunction of the muscles of mastication, and stress is often associated with this dysfunction [5–7]. This dysfunction can also be associated with macrotrauma, such as a motor vehicle accident, or microtrauma, such as teeth grinding and clenching at night. Identification of specific mechanical causes is important as well to correct issues that may be lending themselves to TMD. Examples of mechanical causes can be prolonged mouth or upper respiratory breathing, postural abnormalities, and sleeping prone with increased pressure on the TMJ. A third major cause of TMD is dental malalignment. No matter the physical cause, stress and psychosocial impact should always be considerations [5–7].

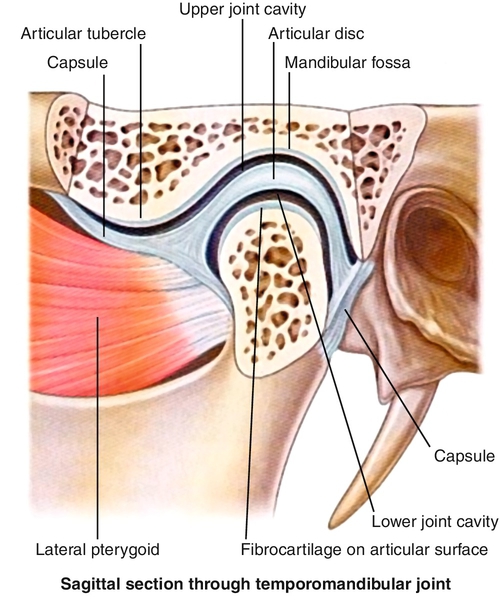

Within the TMJ, there is a biconcave cartilage disc that normally moves with the mandibular condyle in the fossa (Fig. 113.1). The TMJ is a modified hinge joint that has two separate periods and types of motion. In the initial third of opening, the joint moves in a rotational manner. In the latter two thirds of opening, the joint moves in both a rotational and translational motion, allowing increased range of motion. Muscles commonly involved with TMD are the temporalis, masseter, and internal and external pterygoids. The TMJ is innervated by branches of the mandibular nerve. Irritation to these nerves, muscle spasms, intra-articular disease, and myofascial irritation can cause symptoms related to TMD [8].

Symptoms

Symptoms of TMD are varied and may at first seem unrelated. A common complaint with which patients may present is noise stemming from the TMJ, including crepitus, clicking, grinding, and popping. Pain at the level of the TMJ or surrounding areas also is a common complaint that may lead a patient to seek care from a health care provider. Whereas pain directly over the TMJ or mandible may lead patients to believe that they have a problem with the jaw, TMD can often be manifested as nontraditional headaches or upper cervical pain as well and is often made worse with chewing. Another common complaint in TMD is decreased range of motion of the jaw with “locking” of the joint in severe cases. Other symptoms, such as generalized facial pain, earaches, tinnitus, dysphagia, and even photosensitivity, have been reported with TMD [7,9].

Physical Examination

The diagnosis of TMD is made by observation of the range of motion of the mandible and palpation of the musculoskeletal structures of the face and head. It is essential to determine whether the patient has an intrinsic or extrinsic dysfunction of the TMJ. The translation can be felt by placing a finger over the TMJ just anterior to the tragus of the ear and asking the patient to open the mouth wide and repeat this motion. With palpation, the provider should identify whether the movement is smooth or if crepitus or joint dysfunction is noted. At maximal mouth opening, measure the opening in millimeters between the upper and lower incisal edges; the normal range is between 38 and 45 mm [10,11]. The average individual should have roughly three fingerbreadths between the teeth without any discomfort or pain. Monitoring of mandible opening for lateralization during opening can also suggest pathologic change. Have the patient also move the mandible left and right, noting restriction on one side versus the other or pain with this motion.

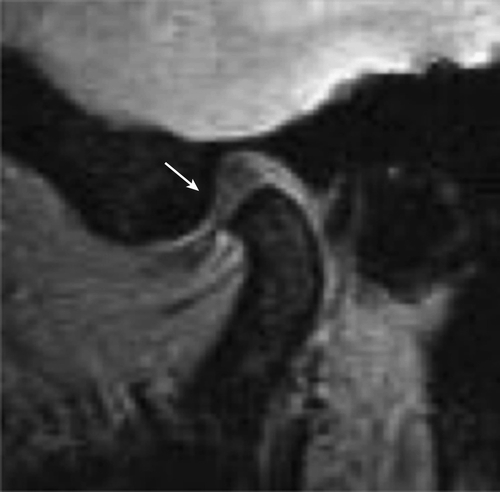

If the disc in the TMJ is displaced (Fig. 113.2) or if there are arthritic changes, clicking and crepitus can be heard or palpated as the disc clicks into its normal position with jaw opening. There will also be a click as the disc slips out of its normal position on closing. If the disc is fully displaced (anterior disc displacement with no reduction), there is no clicking and limited opening with an opening shift toward the locked side and no lateral movement toward the contralateral side. Full lateral and protrusive movements with limited openings might suggest muscle spasm versus disc displacement.

The provider gently palpates both masseters and temporalis muscles, insertion of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, and suboccipital area; any sensitivity should be noted. If the TMD symptoms are of new onset after trauma, a thorough cervical spine examination should be completed as well.

Functional Limitations

Pain may limit speaking and mastication. In patients with chronic pain, sleep and mood disorders may persist as well. Underlying psychosocial stress or depression that may be leading to TMD must also be identified as a possible hindrance of function [6].

Diagnostic Studies

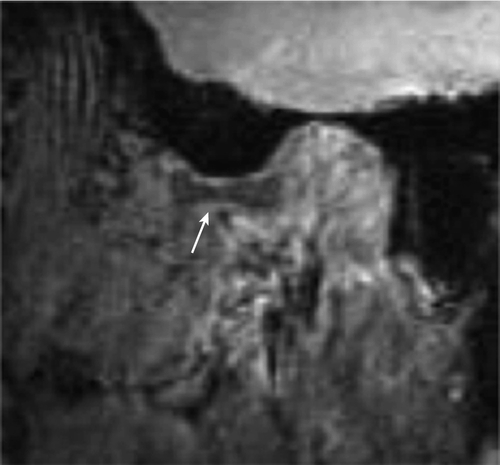

Radiography can identify major arthritic changes, malalignments, or fractures but is not diagnostic if there are no abnormal findings. If it is available, panoramic oral radiography may be beneficial to visualize bilateral TMJs and alignment. Magnetic resonance imaging is necessary to visualize the disc and to provide definitive diagnosis of the disc position (Fig. 113.3), but it is not generally required for nonlocking joints that click [5,8].

Treatment

Initial

There are different philosophical approaches of dental clinicians managing TMD. Some dentists attempt to calm symptoms with oral appliances and have the patient discontinue the daytime appliance after the first few months. Others believe that permanent bite changes are necessary for long-term relief and will grind the bite surfaces of teeth to balance the irregular bite. If there is dental malalignment, an occlusal stabilizing appliance may prove beneficial.

Acute pain with full lateral mandibular excursive and protrusive movement is treated as an acute muscle spasm. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, moist heat, and ice massage as well as eating of softer food during the acute period may decrease pain and ease the burden on the musculature [10]. If the pain does become chronic in nature, lasting more than 3 months, more attention should be paid to stress as a common cause, and medications that treat both pain and emotional stress, such as tricyclic antidepressants, should be considered [7].

Rehabilitation

Manual manipulation can be beneficial in treatment of TMD when the underlying dysfunction is myofascial or muscle spasm. For a unilateral muscle spasm causing TMD, the muscle energy technique takes the patient’s mandible away from the restriction and into the barrier away from the direction of chin deviation, and the patient pushes back three times. After the third activation is completed by the patient, the provider should take the jaw laterally to the physiologic barrier. If a patient has bilateral muscle spasms, have the patient open the mouth against resistance and close the mouth against resistance, repeating each three times to attempt to release the TMJ complex. For more complex TMD cases in which there is some locking, an intraoral technique may be used. In this technique, the provider should put on gloves (with cotton or gauze wrapped around the thumbs). Start by placing the thumbs on the patient’s lower molars and wrap the remaining fingers around the ramus of the mandible, pushing inferiorly and anteriorly until release is felt. This technique stretches bilateral muscle groups at the same time as well as allows myofascial release [11].

Jaw exercises and stretching of the muscles of mastication are paramount to treatment of acute TMD as well as to prevention of progression or recurrences. Following Rocabado’s original research, main goals should focus on joint distraction, elimination of compression, restoration of physiologic articular rest, mobilization of soft tissues, and improvement in the condyle-disc-glenoid fossa relationship. A working example of this exercise is the placement of hands under the chin and opening downward with pressure against the hand for a few seconds at a time for six times, six times a day (classic six by six exercises), which may benefit the patient [12].

Stress reduction and biofeedback to decrease teeth grinding or clenching can be beneficial to help break acute spasms and to avoid progressive weakness or dysfunction.

Correction of posture also may be beneficial to patients suffering from TMD. Holding a posture with increased thoracic kyphosis and decreased cervical lordosis (forward leaning) can increase stress on the TMJ as well as lead to myofascial dysfunction. Other postural issues, such as postures or chronic dysfunction of the subcranial spine, most notably the occipitoatlantal joint, can contribute to TMJ pain. Correction of this posture with exercise and active therapy, such as chin tucks and scapular retraction, is recommended. Also, for patients who tend to sit in this head forward position, a lumbar roll or support while sitting may also be beneficial.

Along with the multiple modalities discussed, the patient should be counseled on avoidance of specific tasks that may exacerbate the symptoms or stress the jaw, such as yawning, singing, chewing gum, or resting the chin on a hard surface.

Procedures

For patients diagnosed with a myofascial cause of TMD, trigger point injections are a viable option to aid in release of the taut bands within these muscles. For recurrent myofascial cases, trigger point injections should be considered an adjunct to continuing therapy to correct the mechanical issues leading to repeated episodes. Intra-articular injections may be beneficial for patients with TMD that has not responded to more conservative treatments. Multiple injectants have been used in TMJ dysfunctions, including local anesthetic, steroids, and viscosupplementation [8,13]. Botulinum toxin has also demonstrated some efficacy in refractory cases and may be considered before surgical intervention [14].

Complementary medicine techniques can also be considered in approaching the treatment of a patient with TMD. For example, Chinese scalp acupuncture can play a role in management. This technique addresses the sensory area of the scalp for abnormal sensations of the face that are hypersensitive, including pain, tingling, and numbness. Treatment by scalp acupuncture has shown positive results in disorders with TMJ pain. Treatment of the lower two fifths of the sensory area focuses on the face, head, and TMJ pain, and it has proved to be a useful adjunct to current treatments [15].

Surgery

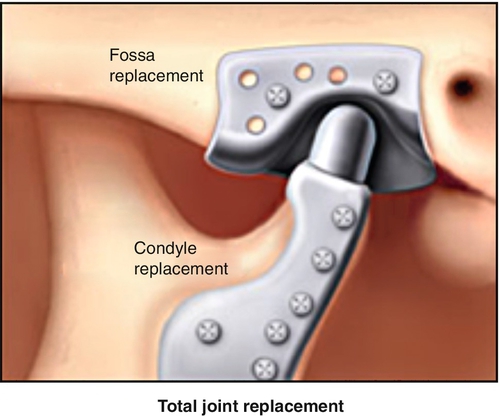

Although surgery is rarely needed, there are surgical procedures that may benefit patients with refractory TMD. If imaging demonstrates intra-articular bone or disc fragments, surgical removal is an option. For patients with refractory TMD not responding to less invasive treatment, shaving of the condyle has also been shown to be beneficial. A joint replacement is possible for the TMJ, allowing return to function (Fig. 113.4). This is more often used when there is significant ankylosis of the joint, which may be seen in patients with severe cases or with a neurogenic cause due to paralysis of the muscles of mastication.

If the problem persists for several weeks or remains refractory to initial treatments and therapies, referral to a provider specializing in TMD may be warranted. When there is unilateral restricted translation of the TMJ and limited opening with a deviation or acute inability to close the mouth, called an open lock or subluxation, consultation with a TMD specialist with experience in unlocking these subluxations is recommended.

Potential Disease Complications

A potential complication is bruxism or rhythmic grinding of the teeth from other conditions, such as traumatic brain injury, especially at night. Trismus, or overactivity of the muscles of mastication, can restrict jaw mobility and be a severe functional problem. If there is anterior disc displacement without reduction, it can limit mouth opening on that side and cause significant pain if there is forced opening. Degenerative joint disease in the older population can affect the TMJ with increased symptoms of pain, tenderness, crepitus, and limitations of jaw movement. TMJ ankylosis may occur from rheumatoid arthritis or trauma, and surgery is often needed. Infections of the TMJ are rare, and there are usually local or systemic signs of inflammation. Finally, local TMD pain during several months can become a widespread chronic pain disorder affecting sleep and causing mood swings, depression, and anxiety.

Potential Treatment Complications

Oral appliances used 24 hours a day for many months may create a permanent bite change. When this occurs, the patient cannot bring his or her teeth fully together when clenching. If it is not properly managed, this may increase symptoms. Athletic mouth guards bought in stores and heated to conform to bite may aggravate TMD symptoms. Inherent risks in injection techniques include ecchymosis, bleeding, infection, and vascular or nerve damage. Medications used to treat TMD carry the same risk as they would for treatment of any pain condition as defined by each individual medication. Surgical interventions have risks similar to those of any open surgical procedure, and these should be discussed between the surgeon and the patient.