CASE 111

History: A 55-year-old man presents with altered blood in the stool.

1. What should be included in the differential diagnosis of the imaging finding shown in the figure? (Choose all that apply.)

2. The patient has been undertreated for ulcer disease because he has persistent Helicobacter pylori infection. Which of the following conditions is associated with the highest prevalence of H. pylori infection?

3. What is the most common complication of chronic duodenal ulceration?

4. Which of the following statements regarding the imaging of complications of duodenal ulceration is true?

A. On plain radiography, the most common appearance is gastric outlet obstruction.

D. The absence of pneumoperitoneum excludes perforation.

ANSWERS

CASE 111

Duodenal Scarring

1. B, C, D, and E

2. C

3. B

4. C

References

Nadgir RN, Levine MS. Update on. Helicobacter pylori. Appl Radiol. 1999.10–14.

Cross-Reference

Gastrointestinal Imaging: THE REQUISITES, 3rd ed, p 90.

Comment

There are four major complications of duodenal peptic ulceration: hemorrhage, obstruction, perforation, and penetration. Complications occur in 1% to 2% of patients per year and are more likely to occur in patients with chronic ulceration.

Bleeding from a peptic ulcer is a common medical condition with high patient morbidity and high medical and hospital care costs. Patients present with hematemesis (vomiting of bright or altered blood) or melena (black, tarry stools) or both. Hematochezia may occur if bleeding is massive. Ulcer hemorrhage is usually managed with fluid and blood resuscitation, medical therapy, and endoscopic intervention; a few patients require surgery. Imaging has very little role except in the very few cases in which therapy has been unsuccessful and the patient is unsuitable for surgery. Angiography is used to identify the bleeding vessel and attempt intervention with vasoconstrictors or embolization.

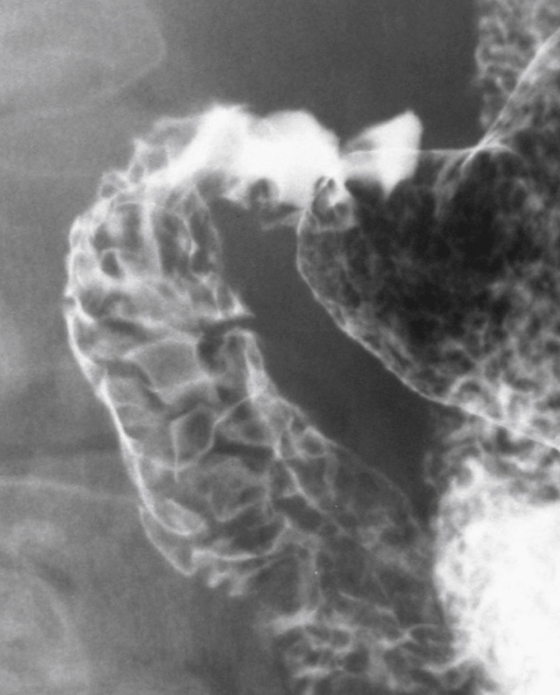

Obstruction is the least frequent complication of duodenal ulceration. In the past, obstruction accounted for at least 10% of patients requiring surgery (see figure). Improvements in medical and endoscopic management have resulted in this decrease. Where the obstruction is pyloric, malignancy rather than peptic disease has become a more prominent cause of obstruction.

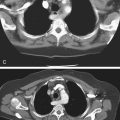

Perforation is potentially the most lethal complication. Patients usually present with sudden onset of severe, diffuse abdominal pain. The duodenum is the most common site of perforation, accounting for 60% of perforations secondary to peptic ulcer. Perforation is a more common complication in patients taking nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and in elderly patients. Imaging is usually limited to the detection of free intraperitoneal air on plain radiography. With this finding, the patient proceeds to surgery. The absence of pneumoperitoneum does not exclude a perforated duodenal ulcer because 20% of patients do not have this sign. CT detects small volumes of pneumoperitoneum. Occasionally, a water-soluble contrast (Gastrografin) study is needed to determine the location of perforation and to determine if leakage is ongoing. Although this is a useful confirmatory test, it is unnecessary in most cases and delays surgery.

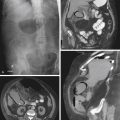

Penetration occurs when an ulcer erodes into an adjacent viscus or other anatomic structure. Penetration occurs in an estimated 20% of cases, although only a few become clinically evident that require specific imaging and management. The pancreas is the most common site of penetration, which usually results in mild hyperamylasemia; clinical pancreatitis is uncommon. Penetration of a duodenal ulcer into a hollow viscus results in various fistulas (gastric, colic, and biliary). Erosion into a vascular structure may lead to catastrophic hemorrhage. Finally, a localized and clinically silent penetration may progress to an abscess.