Oropharyngeal Airway Insertion

PREREQUISITE NURSING KNOWLEDGE

• Oropharyngeal airways are usually disposable and made of hard curved plastic.

• Oral airways are inserted through the open mouth with the posterior tip resting in the patient’s pharynx.

• The oral airway is placed over the tongue. The curvature or body of the airway displaces the tongue forward from the posterior pharyngeal wall, a common site of airway obstruction.

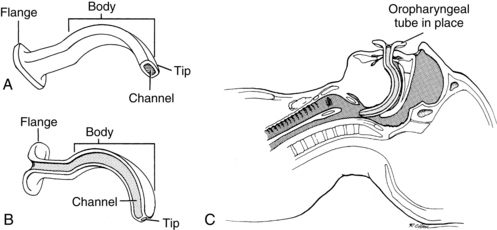

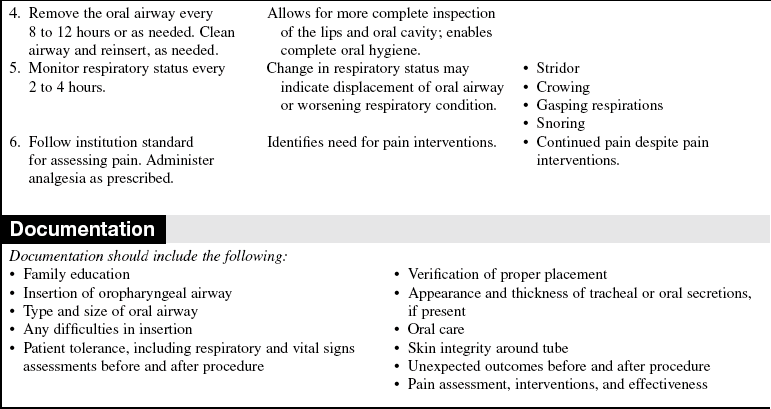

• An oral airway has four parts: the flange, body, tip, and channel (Fig. 11-1). The flange, or flat surface, protruding from the mouth rests against the lips. This design protects against aspiration into the airway. The body of the airway curves over the tongue. The tip is the distal-most part of the airway toward the base of the tongue. The channel enables passage of a suction catheter.

• The Guedel airway is tubular with a flattened-oval inner diameter. A suction catheter passes through the central lumen or channel.

• The Berman airway has a channel on either side that guides the catheter along the edge of the airway into the pharyngeal space.

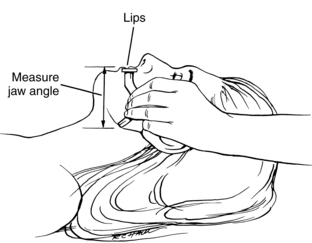

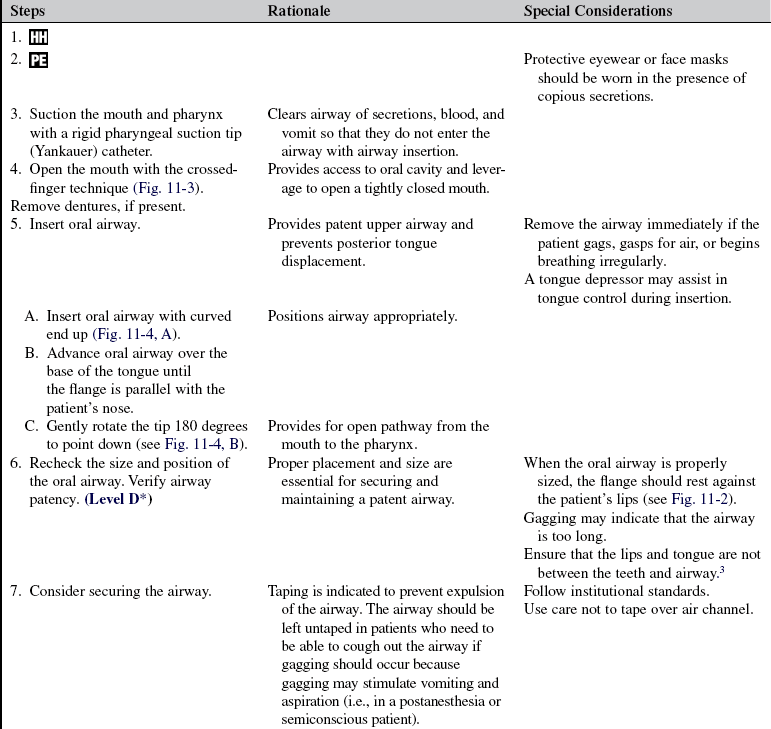

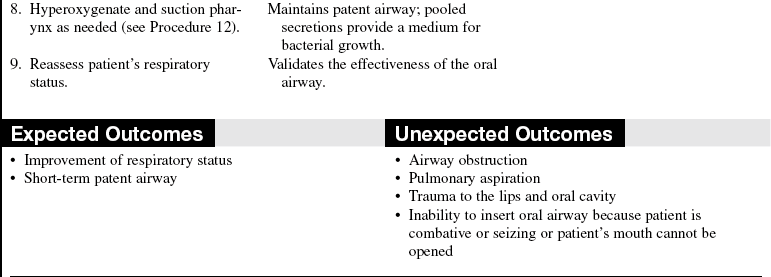

• Oral airways are manufactured in a variety of lengths and widths for adults, children, and infants. Sizing depends on the age and size of the patient (Table 11-1). An alternative method used to select the size of an oral airway is to measure the airway by placing the flange alongside the patient’s lips and the oral airway tip alongside the angle of the jaw (Fig. 11-2). Improperly sized airways can cause airway obstruction (if they are too small) and tongue displacement against the oropharynx (if they are too large).

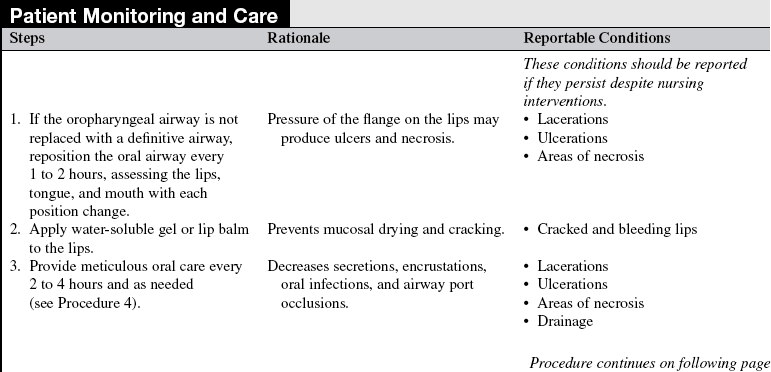

TABLE 11-1

| Size of Patient | Diameter of Oral Airway (mm) | Size of Oral Airway (Guedel) |

| Large adult | 100 | 5 |

| Medium adult | 90 | 4 |

| Small adult | 80 | 3 |

From Cummins RO, editor: Airway, airway adjuncts, oxygenation, and ventilation. In ACLS: principles and practice, Dallas, 2003, American Heart Association, 145.

• Oropharyngeal airways are used most commonly in unconscious patients because they may stimulate vomiting in a conscious or semiconscious patient.2

• Oral airways facilitate suctioning of the pharynx and prevent patients from biting their tongues, grinding their teeth, or occluding their endotracheal or oral gastric tubes. In addition, an oropharyngeal airway may be used in conjunction with an oral endotracheal tube to facilitate artificial ventilation, acting as a bite-block and preventing damage to the endotracheal tube, tongue, and soft tissues of the mouth.

• Improper or rough insertion techniques can result in tooth damage or loss and lacerations to the roof of the mouth. Improper lip, oral, and airway care can result in pressure sores, cracked lips, and stomatitis.

• Oropharyngeal airway placement should never be attempted in a patient who is actively seizing.

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION

• Explain the procedure to the family (if the patient’s condition and time allow) and the reason for the airway insertion.  Rationale: This process identifies family knowledge deficits about the patient’s condition, the procedure, its expected benefits, and its potential risks and allows time for questions to clarify information and voice concerns. Explanations decrease family anxiety.

Rationale: This process identifies family knowledge deficits about the patient’s condition, the procedure, its expected benefits, and its potential risks and allows time for questions to clarify information and voice concerns. Explanations decrease family anxiety.

• Discuss the sensory experiences associated with oral airway insertion, including the inability to clench teeth together, the presence of a hard plastic airway in the mouth, the inability to move the tongue freely, and the possibility of gagging.  Rationale: Knowledge of anticipated sensory experiences reduces anxiety and distress.

Rationale: Knowledge of anticipated sensory experiences reduces anxiety and distress.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT AND PREPARATION

Patient Assessment

• Assess the patient’s need for long-term airway maintenance.  Rationale: Oropharyngeal airways are generally used for temporary airway maintenance.1–3

Rationale: Oropharyngeal airways are generally used for temporary airway maintenance.1–3

• Assess condition of oral mucosa, dentition, and gums.  Rationale: Pre-procedural assessment provides baseline information for later comparison.

Rationale: Pre-procedural assessment provides baseline information for later comparison.

• Remove loose-fitting dentures and any foreign objects (including partial plates, tongue studs, lip rings) from the mouth.  Rationale: Removal ensures that objects do not advance farther into the airway during insertion.

Rationale: Removal ensures that objects do not advance farther into the airway during insertion.

Patient Preparation

• Verify correct patient with two identifiers.  Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

• Ensure that patient and family understand preprocedural teachings. Answer questions as they arise, and reinforce information as needed.  Rationale: This step evaluates and reinforces understanding of previously taught information.

Rationale: This step evaluates and reinforces understanding of previously taught information.

• Position the patient. A semi-Fowler’s or supine position is preferred for a conscious patient.  Rationale: This positioning promotes patient and nurse comfort and provides easy access to the oral cavity.

Rationale: This positioning promotes patient and nurse comfort and provides easy access to the oral cavity.

• Hyperextend the patient’s neck with the head-tilt chin-lift technique or the jaw-thrust technique for opening the airway of the unconscious patient. Maintain cervical stabilization in a trauma patient, using the jaw-thrust technique only.  Rationale: Opening the airway can prevent obstructions that result from posterior displacement of the tongue and epiglottis.

Rationale: Opening the airway can prevent obstructions that result from posterior displacement of the tongue and epiglottis.

References

1. Cummins RO, ed.. Airway, airway adjuncts, oxygenation, and ventilation. In ACLS: principles and practice,. American Heart Association: Dallas, 2006:145–146.

2. Dulak, S. Placing an oropharyngeal airway. RN. 2005; 68(2):20.

3. Pierce, L. Management of the mechanically ventilated -patient,. St Louis: Saunders; 2007.