Introduction 245

The evolving nature of diabetes education 246

Why educate people with diabetes?246

Diabetes self-management 248

Structured diabetes education 248

Planning education 252

Developing educational programmes 254

Topics that require educational input 257

Conclusion 277

References 278

Education has always been fundamental to caring for people with diabetes. Over the last 20 years the process of educating people with diabetes has evolved, moving from a perspective in which education was often a case of ‘telling’ the person certain facts to a more structured and complex activity. Traditionally, people with diabetes assumed a passive role, receiving information that might or might not have been individualised to their lifestyle. Currently, a more active role on the part of the person with diabetes is advocated, in which choice and participation is promoted. In addition to offering information, education should help people to acquire psychomotor and problem-solving skills to enable them to self-manage their diabetes alongside all the other demands of daily living. Diabetes education is a major challenge for healthcare professionals as the number of people with diabetes and the complexity of self-management continues to increase.

This chapter considers the development of diabetes education, from provision of information to a more complex activity in which the individual’s capability to actively self-manage a difficult chronic condition. The process of providing education will be discussed, as will a range of topics that are to be covered when providing a comprehensive education programme to enable people to successfully self-manage their diabetes.

During the last 20 years, great changes have occurred in the provision of diabetes services. The delivery of care has moved to being based predominantly in primary rather than secondary care, the diabetes teams have extended and become more specialised and the role and number of diabetes nurse specialists and practice nurses has radically altered the composition of the diabetes work force. Furthermore, the incidence of diabetes has increased and the treatment and management regimens are much more complex.

In view of such changes it is not surprising that diabetes education has also progressed. Lucas and Walker (2004) reviewed the changing modes of diabetes education over the last 20 years and noted that during the 1980s and early 1990s education was usually delivered during a routine hospital outpatient clinic. It was likely that the education was largely didactic in nature, conventionally the healthcare professional would give advice and information to the individual in the expectation that the advice would be followed. This approach did not allow individuals to balance diabetes self-management with the exigencies of daily living, for example, not having time to make a healthy meal, being unable to eat at an ideal time or not being able to take exercise despite knowing that this would benefit blood glucose levels. Individuals need to know how to manage these situations and such problems cannot be left to be successfully resolved at the next clinic visit. Didactic teaching did not help people to develop skills in which trade-off and compromise were acceptable.

As it was realised that an ad hoc approach to education was not ideal, more structured approaches were required. In addition, programmes that fostered decision making and problem solving, as well as providing the baseline information for diabetes self-management, were required. The expansion in the numbers of people presenting with diabetes and the increasing complexity of management regimens necessitated a greater involvement of all healthcare professionals in diabetes care. Of particular importance is the increase in the numbers of specialist dieticians, specialist podiatrists, diabetes nurse specialists, practice nurses, nurse practitioners and community nurses, who all play a major part in the development and delivery of diabetes education programmes.

WHY EDUCATE PEOPLE WITH DIABETES?

It is generally accepted that people need knowledge and skills, and the motivation to use these, to begin self-management of diabetes. According to the European Diabetes Policy Group Guidelines (International Diabetes Federation (IDF) Europe 1999a) for those with type 1 diabetes:

Similarly, for those with type 2 diabetes:

It is the responsibility of the diabetes team to ensure that the person with diabetes can follow the life-style of their educated choice, achieved through the three elements of empowerment: knowledge, behavioural skills and self-responsibility. (IDF 1999b, p. 719)

These quotations plot out the scope of education and immediately indicate that knowledge alone is not the goal. Knowledge is essential, but on its own is not enough, to enable effective self-management of diabetes (Snoek 2003). If educating people was simply about remedying an information deficit then the task would be easier. When psychomotor skills and psychological attributes such as empowerment and self-responsibility are added in, the whole endeavour becomes more challenging.

The definitions and guidelines from the IDF were designed to ensure that diabetes strategies were consistent at a European level, however, the sentiments are also endorsed at more local levels. For example, the National Service Framework (NSF) for Diabetes (Department of Health (DH) 2001a) published 12 standards, the third of which emphasised the need for a broad reaching view of educating people with diabetes. The aim of Standard 3 was:

To ensure that people with diabetes are empowered to enhance their personal control over the day-to-day management of their diabetes in a way that enables them to experience the best possible quality of life.

The accompanying standard is set as follows:

All children, young people and adults with diabetes will receive a service which encourages partnership in decision-making, supports them in managing their diabetes and helps them to adopt and maintain a healthy lifestyle. This will be reflected in an agreed and shared care plan in an appropriate format and language. Where appropriate, parents and carers should be fully engaged in this process.

When the details of the standard are considered in greater detail it can be seen that education is at its core. The range of the standard covers much more than an understanding of diabetes as a medical condition. To experience the best possible quality of life might also involve, for example, symptom management, access to social and other services, managing work and the resources of employment services and developing strategies to deal with the psychological consequences of illness.

DIABETES SELF-MANAGEMENT

Successful diabetes self-management is notoriously difficult to achieve. Research relating to diabetes self-management confirms that people with diabetes are often unable to manage their condition as fully as might be desired by themselves and by healthcare professionals (Donnan et al 2002, Reed et al 2003, Vermeire et al 2003). Suboptimal self-management can translate into poor metabolic and psychological outcomes, although as DeVries et al (2004) point out, the causes of suboptimal glycaemic control are multifactorial. Furthermore, developing educational interventions to help improve self-management is also difficult (Hampson et al 2001, Norris et al 2001).

STRUCTURED DIABETES EDUCATION

Although a robust case can be made for the need for education, the way in which it is best provided is not clear. For example, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE 2003) conducted a systematic review of the available evidence to inform the provision of educational programmes. As a result of the review it was not possible to advocate any particular educational programme. However, it was possible to recommend that a programme of structured diabetes education covering all major aspects of diabetes self-care should be made available to all people with diabetes shortly after diagnosis and then on an agreed continuing basis.

The provision of education is a complex intervention and, as such, it is a difficult area to research. Despite the wealth of papers dealing with education of people with diabetes the quality of research on this subject has often been criticised (Brown 1992, Ellis et al 2004, Griffin et al 1998). Cooper et al (2001) explored the effects of education by analysing 12 meta-analyses based on research into education for people with a chronic disease where behaviour modification is a part of the treatment regimen. While this review was broader than diabetes, they found that the methodological rigour of the research was often poor; therefore, despite a large volume of work being conducted, it was not of good-enough quality to enable it to be used as evidence on which to base practice. Nonetheless, the authors were able to recommend that ‘practitioners use theoretically based teaching strategies which include behaviour change tactics that affect feelings and attitudes’ (Cooper et al 2001, p. 107).

Healthcare professionals are therefore often in a situation where they must provide education programmes for people with diabetes but there is a dearth of information to inform their practice. This is an area that is now receiving greater attention. For example, if the Diabetes UK website is consulted (www.diabetes.org.uk), a range of studies evaluating education programmes can be viewed.

The NICE Health Technology Appraisal mentioned above (NICE 2003), described structured education as:

A planned and graded programme that is comprehensive in scope, flexible in content, responsive to an individual’s clinical and psychological needs and adaptable to his or her educational and cultural background.

In response to the NICE report, the Department of Health and Diabetes UK established the Patient Education Working Group in May 2004, which reported in 2005 (DH & Diabetes UK 2005). The working group established a set of criteria with recommendations that implementation of the criteria would ensure a high-quality, structured diabetes education programme. These are:

▪ have a stated philosophy

▪ to have a structured, written programme

▪ to have trained educators

▪ to be quality assured

▪ to be audited.

Three of the most widely cited structured education programmes that fulfil these criteria are: the Diabetes Education for Self-Management for Ongoing and Newly Diagnosed programme (DESMOND see: www.diabetes.org.uk and www.desmond-project.org.uk); the Dose Adjustment For Normal Eating (DAFNE Study Group 2002) and the Diabetes X-PERT Programme. These will be considered in turn.

DIABETES EDUCATION AND SELF-MANAGEMENT FOR ONGOING AND NEWLY DIAGNOSED

Whereas DAFNE is designed for people with type 1 diabetes, the Diabetes Education and Self-Management for Ongoing and Newly Diagnosed (DESMOND) programme provides structured self-management group education to individuals who are newly diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. The DESMOND programme was based on chronic disease management programmes in the USA and European models of care that included structured diabetes education. At the time of writing, the programme is being evaluated according to the Medical Research Council Framework for evaluating complex interventions (Campbell et al 2000). A randomised controlled trial, the largest of its kind in newly diagnosed adults with type 2 diabetes, is in progress and is due to report in 2007.

The programme can be offered as a 1-day 6-hour programme or in two half-day sessions or three 2-hour sessions. Groups consist of between five and ten individuals and are facilitated by two trained educators. Part of the programme involves personal goal setting and action planning to achieve goal outcomes. Goal setting and action planning increases self-efficacy and this has been shown to lead to improved biomedical and psychosocial outcomes (Bodenheimer et al 2002, see Chapter 3).

Meanwhile in the UK and, following NICE guidance mentioned above, the DESMOND programme is being rolled out to primary care services with the backing of the DH. It is considered to be the only widely available programme that currently fulfils the criteria for structured diabetes education for people with type 2 diabetes.

There are other examples of structured diabetes education programmes (Everett et al 2003, Sumner & Dyson 2004) and research in which structured diabetes education has been evaluated (Anderson et al 1995, Cooper et al 2003, Griffin et al 1998, Hampson et al 2001, Norris et al 2001, Trento et al 2002). All this work is contributing to an evidence base to guide this area of practice and in so doing is slowly making up for a long-recognised deficit in this aspect of care.

DOSE ADJUSTMENT FOR NORMAL EATING

One programme that has been specifically applied to diabetes is the Dose Adjustment For Normal Eating (DAFNE) project. This programme, which is jointly funded by the DH and Diabetes UK, involves structured training in intensive insulin therapy and self-management. The main principles of the course are:

▪ that individuals learn the skills required to adjust insulin to match the free choice of carbohydrates eaten during a meal

▪ to promote self-management and independence from the diabetes care team

▪ to do this using the principles of adult education in a group setting.

The programme is based on a well established and evaluated inpatient model pioneered in Düsseldorf (Muhlhauser et al 1987). The objective of the programme was to evaluate whether such a training programme could lead to improved glycaemic control and quality of life (DAFNE Study Group 2002). Further details can be obtained from www.dafne.uk.com.

Sue, (case Study 11.1) to complete the DAFNE programme would have participated in 5 days of outpatient training. The overall aim was to enable Sue to enhance her self-management abilities and gain confidence and, subsequently, independence from her diabetes team. She would have been in a group of six to eight people in which three main topics are covered: (1) nutrition, (2) dose adjustment of insulin and (3) preventing and managing hypoglycaemia and hyperglycaemia and managing special circumstances such as exercise. To be able to attend the DAFNE course, Sue would have needed to attend an approved hospital diabetes centre that met specific criteria. To be an approved site, the diabetes centre staff would have completed a DAFNE Educator Programme and be registered as DAFNE educators. It is preferable that at least four members of staff are trained and registered to deliver the DAFNE programme. Another criterion required for approval is that the whole diabetes team must be committed to the philosophy of DAFNE. This philosophy states that the culture of the diabetes centre must be supportive of autonomous, knowledgeable people with diabetes. It is essential that the whole team commits to this and not just the registered educators.

Case study 11.1

Sue had lived with type 1 diabetes for 29 years. She had been on a multiple injection regimen of insulin for the past 10 years and regularly monitored her blood glucose levels. She had been frustrated because despite doing her best she found that adjusting her insulin doses was a bit ‘hit and miss’ and she often ended up with too high or too low readings. She felt angry much of the time, and burdened – as if diabetes ruled her life. She attended a DAFNE training programme and learned (or in her case relearned) about carbohydrate counting. She also learned a more precise method of working out exactly how much insulin she needed for the amount of carbohydrate she ate. By following this regimen she managed to reduce her insulin dose and yet be more flexible with her diet in terms of quality and quantity. Her glycaemic control improved, she had less hypoglycaemia and she managed to lose some weight. She described her new knowledge and skills as ‘liberating’.

Hence, Sue would remain on her multiple injection regimen as this will maximise her opportunities for dose adjustment. Sue would learn how to use quick-acting insulin according to the amount of carbohydrate that she had eaten. During the DAFNE programme, she would have worked out how many units of quick-acting insulin she needed for each 10 g of carbohydrate that she ate. This ratio of insulin units : carbohydrates varies from person to person and sometimes at different times of the day. During the DAFNE programme, Sue had worked out that her insulin units : carbohydrate portion ratio was as follows:

▪ Breakfast: 2 units of quick-acting insulin per 10 g of carbohydrate.

▪ Lunch: 1 unit of quick-acting insulin per 10 g of carbohydrate.

▪ Evening meal: 1 unit of quick-acting insulin per 10 g of carbohydrate.

As part of the DAFNE programme, blood glucose targets are agreed between the person with diabetes and the DAFNE team. Targets are agreed for fasting levels of blood glucose, pre-meal and bedtime. The actual ratio of insulin dose to carbohydrate portion is explained during the programme and individualised to each person. The above ratios are presented as an example only and will differ from person to person.

DIABETES X-PERT PROGRAMME

A more locally based structured education programme, which has been evaluated by a randomised controlled trial, is the Diabetes X-PERT programme. This is based on the theories of empowerment and discovery learning for adults. Results were positive in the biomedical and psychosocial outcomes of the programme. This programme offers training and quality assurance for healthcare professionals. Further details can be found on www.xpert-diabetes.org.uk. (Department of Health (DH) 2001b).

PLANNING EDUCATION

Education can be facilitated on a one-to-one basis, in small groups or in a more formal seminar or discussion group. However, adults learn best when the principles of adult education are used (NICE 2003). Education can take place in a person’s home, at a health centre or at a diabetes centre, in the community or in hospital. While it is crucial that a structured programme is the foundation of education, casual and opportunistic education will also occur in relation to episodes, such as illness, that demand new or revised knowledge and skills. Much has been written about group education versus individual education (Cooper et al 2002, Griffin et al 1998, Sumner et al 2001) and the balance will depend on circumstances, such as numbers of people requiring education and staff resources. Whereas education for those with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes is usually delivered on an individual basis, increasing numbers of people newly diagnosed with type 2 diabetes are lending themselves to group education. As yet, there is little evidence to inform the relative merits of which approach is best employed, with which type of person and in which circumstances. However, group education should also be seen as an opportunity for individuals to share experiences and offer each other mutual support.

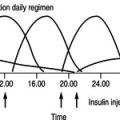

VISUAL AIDS

Materials used for education will include audiovisual and computer-based material, posters, leaflets, diagrams and practical equipment such as food models. Visual aids should encourage interaction between educator and the person with diabetes (Llahana et al 2001). Materials are very important to assist with the educational process and must be of the highest standards of accuracy as well as comprehensible, relevant and culturally specific.

Healthcare professionals using literature to support their education sessions should be aware of the problems of readability and literacy status of the material that they use. These problems are compounded where English is not a person’s first language. There is, therefore, a considerable need for educational materials which are culturally specific. Diabetes UK has made a determined effort to provide educational material suitable for a wide range of individuals, cultures and topics (see www.diabetes.org.uk).

TIMING OF EDUCATION

At diagnosis, the person newly diagnosed with diabetes is usually anxious and although appearing keen to learn, is not necessarily in the most receptive frame of mind to acquire new knowledge. An education programme must therefore be planned and staged to take into account the person’s ability to assimilate information (Coates 1999).

The first stage of education commences at the time of diagnosis. The person will require emotional support and might want to ask questions regarding diagnosis, cause and implications of diabetes. This is a time when the educator will learn about the physical, psychological, spiritual and cultural needs of the individual and what is important to him or her. For example, the newly diagnosed individual might be terrified that the diagnosis will impact negatively on work or relationships, or on his or her abilities to be a parent or indeed to become a parent. A needs assessment will inform the educational content of immediate and ongoing education. The educational programme should be structured to provide the person with essential facts based on what questions he or she is asking and what he or she needs to know to be safe.

When commencing education with the individual concerned, it is important to determine first how much the individual already knows about diabetes and to discuss any misconceptions that he or she might have. It is common for people to be aware of the worst complications of diabetes, such as amputation or blindness, and many believe that these are inevitable.

The second stage requires a learning plan that has more detailed education on aspects of diabetes that address both the individual’s agenda and that of the educator (Box 11.3). Although the healthcare team has its own agenda for education, individuals determine which area they want to learn about next. Educational material must be presented in small, bite-sized chunks to enable the person assimilate it. Inviting questions, reiterating and encouraging the person to verbally reflect what has been said will assist the individual to make sense of his or her new knowledge and relate it to his or her own circumstances. Reinforcement with written material will help the individual to remember new facts but should not be a substitute for face-to-face collaborative education (Ellis et al 2004). It is good practice to review what the person understands of the content covered at a previous session prior to moving on to the next topic. This helps to secure the knowledge and skills acquired and give an opportunity to discuss how these have been implemented into the real world of living with diabetes. Collaborative goal setting will help the individual to ground his or her new-found knowledge into his or her unique circumstances.

Checklist detailing recording of topics in diabetes education programme

Alcohol

Contact numbers

▪ surgery

▪ community nurse

▪ hospital clinic

▪ diabetes nurse specialist

Complications

▪ annual review

▪ eyes (blurred vision at diagnosis)

▪ kidneys

▪ feet

▪ blood pressure/coronary heart disease

▪ sexual health

Diabetes UK

Department of Social Security benefits

Diet

▪ seen by dietician

▪ date to see dietician

▪ current weight, body mass index and waist size

▪ importance of regular meals (people with type 1 diabetes especially)

▪ diabetic foods

▪ alcohol

▪ special occasions

▪ what to do when unwell

Driving

▪ DVLA

▪ insurance

▪ planning a long journey

▪ what to do if hypoglycaemic (not relevant if controlled by diet or a biguanide)

Employment

▪ informing employer

▪ shift work

▪ can register disabled

Exercise

▪ benefits of exercise

▪ forms of exercise

▪ adjusting insulin (if relevant)

▪ adjusting diet

Hypoglycaemia (if relevant)

▪ what causes it

▪ how to recognise it

▪ how to treat it

▪ what happens if you do not recognise or treat it

▪ telling your family and friends

▪ telling employers

▪ exercise

▪ driving

▪ nocturnal hypoglycaemic episodes

▪ use of glucagon

Hyperglycaemia

▪ what does it feel like

▪ what causes it

▪ how to recognise it

▪ how to treat it

▪ what happens if you do not recognise or treat it

▪ when to call for help

Identification

▪ carry identification of diagnosis of diabetes

Insulin (only if relevant)

▪ how it works

▪ how to inject (including mixing insulins if necessary)

▪ when to inject

▪ where to inject and rotation of sites

▪ storage of insulin and equipment

▪ disposal of equipment

▪ availability of equipment

▪ can relatives inject person?

▪ never omit insulin

▪ how to manage missed injections

▪ insulin dose adjustment

Insurance

▪ car insurance

▪ life insurance

Monitoring

▪ blood glucose/urinary glucose

▪ when to test

▪ recording results

▪ explanation of results

▪ goals to aim for

▪ urinary/blood ketone testing (if relevant)

▪ glycated haemoglobin

Oral hypoglycaemic agents

▪ when to take

▪ expected side-effects

▪ what to do if unwell

Podiatrist

▪ referred to podiatrist

▪ seen by podiatrist

▪ foot health education

Prescription exemption (not relevant if controlled by diet alone)

Sexual health

▪ contraception

▪ planned pregnancies and why

▪ impotence

▪ menopause

Smoking

▪ help to stop

Stress

Travel and holidays

▪ lying in

▪ adjusting therapy

What is diabetes?

What to do if unwell?

For education to be effective, it must be reinforced and the person motivated in self-management. This is the third stage in education. A multitude of evidence demonstrates that educational interventions work for a limited period of time only. Stressful periods (see Chapter 3) get in the way of the hard work that optimal self-management requires. Hence, education becomes a lifelong process and includes facilitating individuals in problem solving to manage new situations.

DEVELOPING EDUCATIONAL PROGRAMMES

According to the NICE report (NICE 2003), there are no trials specifically concerned with the content of initial education for those with type 1 diabetes. However, there is a reasonable consensus of professional opinion of the important issues that should be included in diabetes education programmes (Audit Commission 2000, International Diabetes Federation (IDF) Europe, 1999a and International Diabetes Federation (IDF) Europe, 1999b, NICE 2003). As education is delivered by a multidisciplinary team it is vital that the content of education is agreed to avoid conflicting information. All members of the team will be involved in educational care from time to time as the need arises. When developing programmes, people with diabetes should be involved to help determine content as it is known that healthcare professionals and individuals with chronic diseases have differences of opinion regarding the content of educational programmes (Clark & Hampson 2003, Woodcock & Kinmonth 2001).

PEOPLE WITH TYPE 2 DIABETES

For most people, the diagnosis and management of type 2 diabetes starts in general practice. At the first visit after diagnosis, the person might well be bewildered and hence not very receptive to education. However, some ‘first aid’ measures are appropriate until the next appointment. These would include a simple explanation of diabetes, simple adjustments to diet following the taking of a dietary history and, for some, the commencement of monitoring might be appropriate (Box 11.1). The person should be advised regarding contact numbers should there be a problem.

Suggested staged approach to the education of the person with type 2 diabetes

First clinic visit

▪ answer person’s questions

▪ simple explanation of diabetes

▪ dietary history and some adjustments

▪ choice of monitoring and how to undertake it (if advocated)

▪ screening for complications, e.g. blood pressure, neuropathy, feet, eyes, proteinuria/microalbuminuria

▪ assess smoking status and offer cessation advice if necessary

▪ contact numbers

Second clinic visit

▪ answer person’s questions

▪ dietary reinforcement and encouragement

▪ assessment of monitoring, review results

▪ explanation as to what affects glucose levels

▪ simple explanation of benefits of good diabetic control

▪ foot health education

▪ prescription exemption (if relevant)

▪ Department of Social Security benefits (if relevant)

▪ driving

▪ related insurances

▪ carry identification that the person has diabetes

▪ Diabetes UK

Third clinic visit

▪ answer person’s questions

▪ dietary reinforcement and encouragement

▪ review monitoring and explain meaning of results

▪ explain the benefits of clinic attendance

▪ simple explanation of diabetic complications and benefits of using the healthcare team to screen for these

▪ benefits of exercise

▪ enabling appropriate self-management during illness or any new problem

▪ progressive nature of diabetes

▪ lifestyle modifications

▪ potential impact on employment

▪ subsequent visits might include education regarding oral hypoglycaemic agents, travel and holidays and hypoglycaemia

As far as possible, the family and friends of the individual should be included. Engaging social support has been shown to improve glycaemic and psychosocial outcomes in diabetes self-management (Van Dam et al 2005). At a further visit, the individual’s questions regarding diabetes would first be addressed.

Monitoring technique would be assessed and the results discussed. From the outset the person with diabetes should be encouraged to make sense of monitoring results with help from the clinician rather than have the clinician immediately offering explanations about reasons for results. As diet is the mainstay of management for the person with type 2 diabetes, more detailed and tailored dietary advice from the dietician would be appropriate (see Chapter 6).

If the person has already started oral hypoglycaemic therapy, it would be appropriate to advise that prescriptions can be obtained free in the UK by completing a FP92A form. This is not available to people who are treated by diet alone.

Education should take into account that people with type 2 diabetes have multiple risk factors contributing to premature cardiovascular disease. Subsequent visits would include education about the personal risk factors for the individual. The person with diabetes then has the knowledge to make decisions about what he or she would like to do to improve his or her risk factors. The individual can identify his or her own personal goals for self-management and an action plan to operationalise goal achievement is put into place. Goals might be to do with taking exercise, dietary changes or finding strategies to take medication regularly. Goals need to be realistic and achievable (see Chapter 3).

Diabetes education will include foot care, the clinic attendance that includes screening for complications and the associated cardiovascular risk factors and the need for exercise. The progressive nature of diabetes, the potential impact on employment, driving and insurance also need to be discussed. Thereafter, all visits are opportunities for revising education and educating people as their management alters or complications develop and progress.

People with type 2 diabetes requiring insulin therapy

In the UK, until recently, most people with type 2 diabetes who required insulin therapy were referred to the local hospital clinic and consequently education was initiated and maintained by the secondary care diabetes specialist nurse (DSN). However, this situation is changing as more practice nurses and community nurses are developing expertise in diabetes care and striving to keep people with type 2 diabetes in their own environment in primary care. The involvement of family and friends is encouraged to dispel some of the myths about diabetes and to promote a positive approach to the individual concerned (Van Dam et al 2005).

One of the main issues for someone with type 2 diabetes starting insulin therapy is weight gain. The nature of type 2 diabetes means that many people are already overweight and might struggle with healthy eating. Insulin therapy in type 2 diabetes can lead to weight gain and associated increasing insulin resistance with limited improvement in glycaemia (UKPDS 1998). Subsequently, insulin doses increase, weight increases and the vicious cycle continues. It is important that the person with diabetes approaching insulin therapy understands why insulin therapy is the optimal treatment. The best way to make sense of this is through blood glucose monitoring. People might also want an opportunity to maximise healthy eating and exercise and observe the impact of this through blood glucose monitoring. If there is no change in results then it will help the individual to know that, despite best efforts, insulin therapy is the only alternative. If there are improvements then, depending on the level of improvement, the individual might need to make a decision about whether these lifestyle options are realistic and sustainable in the long-term.

PEOPLE WITH TYPE 1 DIABETES

The individual with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes would be referred to secondary care services as assessment is required as to whether or not he or she is suffering from diabetic ketoacidosis, which would result in admission to hospital.

Subcutaneous insulin is commenced immediately if the person does not have diabetic ketoacidosis. This is usually done by the DSN in secondary care but as an outpatient or in the person’s own home. The individual is usually in a state of shock at the time of diagnosis. Many of the questions a newly diagnosed person has at this time are around how this could have happened and whether he or she has caused it. In terms of education, people usually respond well to undertaking practical procedures but will not necessarily retain much factual information. Hence, at the first visit, blood glucose monitoring and how to inject insulin will be taught (Box 11.2). When starting insulin therapy, the person will usually be seen at least daily for a few days and thereafter followed up as necessary with telephone contact being maintained by way of further support. Again, a staged approach is required, with more detailed explanations in response to the individual’s questions being introduced over a period of about 6 weeks. As people with type 1 diabetes tend to be seen more frequently, reinforcement of education is easier and individuals have greater opportunities to ask pertinent questions.

Suggested staged approach to the education of the person with type 1 diabetes

First clinic visit

▪ answer person’s questions

▪ simple explanation of diabetes and the actions of insulin

▪ dietary history and some adjustments

▪ initiate home blood glucose monitoring

▪ initiate insulin injections

▪ assess smoking status and offer cessation advice if necessary

▪ identification of diagnosis of diabetes

Within the first week

▪ answer person’s questions

▪ full dietary assessment and adjustments

▪ how to acquire necessary equipment for injecting and monitoring

▪ prescription exemption

▪ Department of Social Security benefits (if relevant)

▪ discuss goals for blood glucose levels using a staged approach

▪ assessment of monitoring technique and review results

▪ explanation of what affects glucose levels

▪ employer

▪ hypoglycaemia

▪ driving

▪ insurances

▪ Diabetes UK telephone number and address

Within the second/third week

▪ answer person’s questions

▪ insulin dose adjustment

▪ foot health education

▪ alcohol

▪ advantages of good diabetic control

▪ the benefits of clinic attendance

▪ explanation of the complications of diabetes and benefits of screening for diabetic complications

▪ benefits and effects of exercise

Within the first month

▪ answer person’s questions

▪ hyperglycaemia

▪ what to do if person is unwell

▪ subsequent visits may include education regarding travel and holidays, sexual health matters, stress related problems

TOPICS THAT REQUIRE EDUCATIONAL INPUT

Many topics need to be covered in an education programme, as illustrated in Box 11.3. The subjects that follow are not intended to indicate the entire range of topics rather they reflect important areas which have not yet been discussed.

The person newly diagnosed with type 1 diabetes or type 2 diabetes will be informed that their blood glucose levels are high. All those with type 1 diabetes will be well aware of the symptoms that took them to see their doctor and these include thirst, polyuria, lethargy and probably a dramatic weight loss (Box 11.4). They might also have experienced Candida, cramps, painful peripheral neuritis and blurring of vision, which are all a consequence of hyperglycaemia (see Chapter 1). If the individual was acidotic then he or she might also have had nausea and/or vomiting and have been breathless. Those with type 2 diabetes might also have had all or some of these symptoms but possibly over a longer period of time and less intensely. Some people will have rationalised their symptoms and decided that they were tired because they were working too hard, or that they were thirsty because the weather had been hot. In helping to make sense of diabetes it is important to explain how the different symptoms relate to the physiology of diabetes and that if these symptoms return then it means that some aspect of treatment and/or self-management needs to be reviewed. Self-referral should be encouraged especially as it has been shown that type 2 diabetes requires progressively increasing treatment over time (UKPDS 1998).

Symptoms and Signs of hyperglycaemia

Symptoms of hyperglycaemia

Polydipsia

Polyuria

Abdominal pain especially in children

Weight loss

General tiredness

Blurring of vision

Itching and skin

Pain and paraesthesia in the feet and limbs

Nausea and vomiting

Signs of hyperglycaemia

Hypovolaemia

Glycosuria

Tachycardia

Dehydration

Acidotic breath

Deep rapid breathing

Skin infections

Confusion and restlessness

Some people with type 2 diabetes might not have experience of hyperglycaemic symptoms if their diabetes had been diagnosed through a screening procedure at work or at a clinic. It can make the diagnosis more difficult to come to terms with if this is the case and blood glucose or urine monitoring can help to accept the reality of having diabetes.

Hyperglycaemia can be due to any one of several factors (Box 11.5). People with diabetes might be anxious about finding that their blood glucose levels are above target levels but can be reassured that they have time on their side to adjust their treatment or to seek advice. Left untreated, metabolic decompensation progresses to a hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic syndrome in the person with type 2 diabetes or diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) in the person dependent on insulin (see Chapter 5).

Factors that affect blood glucose levels

Hyperglycaemia

▪ not enough insulin

▪ not enough exercise

▪ too much food

▪ any other illness

▪ stress

▪ erratic absorption of insulin

Hypoglycaemia

▪ too much insulin

▪ unplanned exercise

▪ not enough food, delaying or missing a meal

▪ recovering from an illness

▪ alcohol

▪ erratic absorption of insulin

Self management during an acute illness has always been an educational challenge because the elements of diabetes self-management during illness might have been taught early on but the individual with diabetes might not experience illness for many years and will have completely forgotten ‘the rules’. The most important advice to be given here is to seek help and to seek it quickly (Box 11.6). People who are unwell lose their appetite and tend to stop their drugs or insulin therapy because they fear hypoglycaemia; however, metabolic control can rapidly deteriorate under these circumstances. Food substitutes are presented in Box 11.6.

What to do if unwell

▪ Do not stop taking medication or insulin

▪ If unable to eat food, take small, frequent amounts of semi-solids. Examples of 10 g of carbohydrate are:

▪ 50 g scoop ice cream

▪ 200 mL milk

▪ 200 mL tomato soup

▪ 50 mL Lucozade

▪ half a small carton of fruit yoghurt

▪ Drink about 3 litres of water or sugar-free fluids per day to prevent dehydration

▪ Increase self-monitoring to twice a day if urine testing and four times a day if blood testing

▪ If facilities are available, test urine for ketones if there is a 2% glycosuria or if blood glucose levels are above 15 mmol/L

▪ Contact the GP or nurse if any of the following apply:

▪ the presence of ketonuria

▪ vomiting

▪ abdominal pain

▪ elevated temperature

▪ the illness has lasted longer than 24 hours

When a person is unwell, in most situations, the blood glucose will rise due to the hormones of stress even if the appetite has been suppressed (see Chapter 1). This means that the individual should not reduce his or her insulin or hypoglycaemic agents but in fact might need to increase the doses. Hence, people who are ill need to increase their monitoring to four times daily.

People with type 1 diabetes need to test their blood or urine for ketones and, if present, should self-refer to their GP, nurse or local accident and emergency centre for assessment. If all else is forgotten, people should be encouraged to remember the golden rule ‘Never stop taking insulin’. Vomiting might be a sign of diabetic ketoacidosis and the individual needs to seek urgent medical help, if not from the GP then again at his or her local accident and emergency centre.

People with type 2 diabetes who are unwell are also encouraged to increase self-monitoring as treatment might need to be started for those controlling their diabetes by diet alone, or treatment adjusted if already on oral hypoglycaemic agents or insulin. People taking metformin should continue with treatment if possible but as metformin needs to be taken with food this may be problematic. Alternative treatment might be required if the illness is prolonged.

Those people who are taking a sulphonylurea (e.g. gliclazide) and/or a thiazolidinedione (pioglitazone or rosiglitazone) need to continue with these but, again, adjustment of the sulphonylurea might be required in prolonged illness. Advice must be sought if there are any elevated blood glucose levels and ketonuria or evidence of raised blood ketones.

The exception to becoming hyperglycaemic during illness is if the person is suffering from a gastrointestinal illness causing diarrhoea but is not affected systemically. In this case, the person might become hypoglycaemic and, should this happen, he or she needs to seek advice. Oral hypoglycaemic medication might need to be stopped for the duration of the diarrhoea and insulin, in people with type 1 diabetes and type 2 diabetes, might need to be reduced. However, insulin in type 1 diabetes can never be stopped (see Box 11.6).

Bill is 38 years old and has had type 1 diabetes for the last 15 years. He has remained fit and well during this time and has been fortunate enough to avoid any serious illnesses since diagnosis. The previous evening, after being out with friends, he began to feel very nauseous. He had a disturbed night during which he vomited and developed abdominal cramps. In the morning he measured his blood glucose level, as was his usual routine, and was a little surprised that it was 15 mmol/L. He could not face any fluids or breakfast and decided to crawl back into bed and take the day off work. As he was not having breakfast he thought he should miss his morning insulin in case he became hypoglycaemic while asleep. By mid-morning he was still nauseated and feeling very thirsty. He called his GP and then went back to bed. His GP visited him and took his temperature, blood pressure, examined his abdomen and then tested his urine and blood glucose. Bill was astonished to learn that his blood glucose was now 24 mmol/L, despite no food, and that he had a large amount of ketones in his urine. The GP arranged for him to be admitted to hospital where his blood glucose levels were brought under control using intravenous fluids and insulin.

Before discharge a nurse discussed with Bill his rationale for missing his insulin. Bill learned the hard way that missing his insulin had resulted in this medically dangerous situation. The nurse helped Bill to make sense of what had happened and he was reminded that he should never stop taking his insulin, even if he cannot take his usual meals. In such circumstances he might even require more insulin depending on his blood glucose levels.

The reasons and significance of why ketones must be monitored if the blood glucose exceeds 10 mmol/L were discussed Even during illness the target blood glucose levels should remain in the 4.0–7.0 mmol/L range. The actual adjustment of insulin will vary according to individual needs.

It emerged that whereas Bill had always attended his clinic appointments he had never faced this situation before so he had never thought to check up on what to do when unwell. This is a common example of the importance of continuing education for people with diabetes.

Education about hypoglycaemia features prominently in caring for people with diabetes. Hypoglycaemia is the most common side effect of insulin therapy or sulphonylurea treatment. Individuals are frightened of hypoglycaemia and so may deliberately keep their blood glucose levels high. People must be taught how to achieve healthy glucose profiles and prevent, recognise and treat hypoglycaemia.

John is a 54-year-old man who was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes 10 years ago. John was controlled on oral medication for the first 8 years following diagnosis. Two years before, despite maximum dose oral therapy and lifestyle changes, John was started on a regimen of a fixed mixture of insulin. John’s current body mass index is 29 kg/m2 and until recently was achieving optimal blood glucose control. At his recent clinic visit John expressed concern about some hypoglycaemic episodes he had been experiencing.

Every year, about 25–30% of insulin-treated people with diabetes suffer one or more severe hypoglycaemic episodes requiring the assistance of others (Williams & Pickup 2004). Symptoms such as hunger, pallor, tremors, palpitations, anxiety and confusion in association with a blood glucose level of less than 4 mmol/L is diagnostic of a hypoglycaemic episode.

The concern expressed by John is both common and well founded, given that hypoglycaemia can lead to both recurrent physical morbidity and to recurrent or persistent psychosocial morbidity and sometimes even death (Cryer 1997).

The issue of hypoglycaemia within type 2 diabetes has received more attention since the reporting of the UKPDS (1998), in which it was noted that 11.2% of people with type 2 diabetes using insulin experienced major hypoglycaemia for which hospital admission was required. More recent studies suggest that this might be an underestimate (Donnelly et al 2005, Leese et al 2003). It is therefore necessary to review the education John received when diagnosed with type 2 diabetes and when he started on insulin therapy. There might be clinical reasons why John has started to become hypoglycaemic and these must be considered. The possible causes of these hypoglycaemic episodes should be discussed (see Box 11.5).

Each of these issues should be discussed in a session with John. On reflection, he might thereafter understand what has caused his hypoglycaemia and also how to prevent it recurring. Sometimes, however, the cause is not obvious and clinical causes should be considered. These include:

▪ Renal impairment causing delayed excretion of insulin or sulphonlyurea.

▪ Rarely, other physical causes such as Addison’s disease or insulinoma.

In the event of no cause being found then insulin needs to be reduced and John is encouraged to learn and become confident in adjusting his insulin.

Treatment should be discussed with John and his family/friends as overcorrection can lead to rebound hyperglycaemia and undercorrection can lead to recurrence of the hypoglycaemic episode within a short space of time. Hypoglycaemia can be treated with:

▪ 10–20 g rapidly absorbing carbohydrate, such as between three and six Dextroenergy glucose sweets, 50–100 mL Lucozade or two to four teaspoons sugar dissolved in water.

▪ This should be backed up with a meal, if it is due, or a snack if the hypoglycaemic episode has occurred between meals. The snack should contain carbohydrate and could consist of two or three biscuits, fruit, crackers or a sandwich.

John should be encouraged to carry fast-acting carbohydrate with him at all times. He should also have a card or equivalent that identifies him as having diabetes in case he should have a severe hypoglycaemic episode that requires external help.

Symptoms of hypoglycaemia vary from person to person and most people experience only one or two of a number of possible symptoms (McAuley et al 2001). John is already clear that his symptoms include tremor and profuse sweating and this wakes him up at night. However, it has been shown that people can sleep through overnight hypoglycaemia and wake up in the morning none the wiser (Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) 1993). A history of headache or feeling ‘hungover’ might be a clue to overnight hypoglycaemia. A nocturnal hypoglycaemic episode is frightening for the individual and their bedfellow! People who require reassurance about this are advised to check their blood glucose level before going to bed at night and, if below 6 mmol/L, to consume extra carbohydrate before sleeping. It might be necessary to reduce the overnight basal insulin; however, the use of a short-acting insulin analogue with evening meal or within a fixed mixture of insulin has also been shown to reduce the incidence of night-time hypoglycaemia (Hermansen et al 2001).

Hypoglycaemic symptoms can be experienced at glucose levels greater than 4 mmol/L. If John’s blood glucose levels had been running consistently high for a period of time then, when the blood glucose falls, John might experience hypoglycaemic symptoms but not be at risk of impaired consciousness. The experience of hypoglycaemia is still very unpleasant and needs to be treated in the same way; however, as John improves his glycaemic control then his symptoms of hypoglycaemia would occur at a lower level.

John is right to be concerned about hypoglycaemia because there is a possibility if he continues to have episodes regularly his warning symptoms will become impaired or lost. If this happens then John would be asked to reduce his insulin doses and run his blood glucose levels at a higher level, completely avoiding all hypoglycaemia for a period of about 3 months. Thereafter, his insulin dose could be increased gradually to optimise glycaemic control and he should then find that his warning symptoms have returned. In a few people, warning symptoms do not return and specialist advice should be sought.

Hypoglycaemia is normally classified as mild (self-recognised and self-treated), moderate (usually conscious and able to self-treat or be treated with help from another person but without emergency intervention) and severe (requires the assistance of a third party and normally emergency intervention). Treatment of hypoglycaemia depends on the individual’s level of consciousness and should preferably be administered after confirmation of blood glucose. If the individual needs help from another (apart from medical help) then there are two treatments that can be administered by others.

Glucose in the form of a viscous gel (‘Hypostop’ now known as ‘Glucagel’) can be squeezed into the mouth if the person is uncooperative and is of particular value in children but should not be used if a person is unconscious.

Left untreated, the person would eventually lapse into a hypoglycaemic coma and would require assistance from someone for treatment. In this situation, relatives and friends can be taught how to administer glucagon 1 mg intramuscularly. Glucagon (known as ‘Glucagen’) is available in convenient packs containing 1 mg of the dried form of the agent and 1 mL diluting solution. The expiry date needs to be checked regularly and another prescription obtained before the current vial expires. Glucagon can be rapidly dissolved and injected subcutaneously or intramuscularly by another adult. A competent healthcare professional can give glucagon intravenously. The person should recover within 10 minutes then be encouraged to consume at least 20 g oral carbohydrate to replace glucose stores.

It is not unusual if a person is in a hypoglycaemic coma for emergency attention to be sought even though relatives or carers administer glucagon. Likewise, it should be sought calmly and quickly in the event of a person’s inability to swallow or loss of consciousness. While glucagon can bring a person out of a comatose state, it is not without its problems. One problem with glucagon is that it can cause nausea and vomiting, so although the person becomes more responsive, he or she may be resistant to eating or drinking. It is, however, necessary for the individual to eat in addition to receiving the glucagon injection to replenish liver glycogen stores and prevent secondary hypoglycaemia.

Glucagon is less effective when the person has been unconscious for a prolonged period of time (Cryer et al 2003). Under these circumstances, an intravenous injection of 50% dextrose is preferred and this is usually carried out in the hospital emergency care department. People can experience a severe headache for up to 24 hours after a prolonged episode of hypoglycaemia. Remember that although used in type 1 diabetes, glucagon is less useful in type 2 diabetes as hypoglycaemia, when induced by sulphonylureas, is often prolonged and a rise in glucose will stimulate a further rise in insulin secretion (Cryer et al 2003).

In the elderly, hypoglycaemia might simulate a transient ischaemic attack or a cerebral vascular accident. It is therefore important to check a blood glucose level in any elderly person who presents with neurological signs. Although these might appear to be of a minor nature, all such individuals should be admitted to hospital for a minimum of 24 hours for observation.

EXERCISE

Exercise has many physical and psychological benefits especially for people with diabetes. A moderate to high level of exercise in people with type 2 diabetes has been shown to reduce the risk of cardiovascular mortality (Hu et al 2005). In another study, regular exercise was associated with reduced development of metabolic risk factors for cardiovascular disease, fewer exercise-induced cardiac abnormalities and reduced comorbidity (Petrella et al 2005). Exercise promotes a feeling of well-being and also improves the tissue sensitivity to insulin, thus decreasing insulin resistance. It is recommended that all people should be advised to maintain at least moderate levels of physical activity on a regular basis (SIGN 2001). The recommended form of exercise builds on what a person currently does rather than commence some new strenuous form of exercise. An example of this would be to increase the distance they walked each day for example, by walking to a further bus stop rather than using the closest one. When discussing exercise with people it is worth mentioning that physical activity such as gardening and housework can be regarded as a form of exercise, and not only those activities associated with recreational exercise. However, for those people with type 2 diabetes who wish to pursue a new form of exercise, a medical examination by their GP is advisable to ensure that there are no contraindications. Warm-up and cool-down exercises are recommended to avoid undue physical stresses to muscles and joints.

Exercise and hypoglycaemia

The person who is taking a sulphonylurea or insulin therapy might be at risk of hypoglycaemia in relation to exercise.

For the person taking insulin, hypoglycaemia can be prevented by reducing the relevant insulin ‘vigorously’ and consume extra carbohydrate during the exercise (Gallen 2005 and see Chapter 6). If the person is overweight, then reduction in insulin/sulphonylurea would be the best option as extra carbohydrate might negate any weight loss intended by the individual. The reduction in insulin dose depends on the intensity and length of time the exercise takes. People are also advised to inject their insulin into their abdomen and so avoid injecting into their ‘active’ limbs, which will increase their absorption of insulin (Frier 1999). People should also avoid exercising at the peak time when their insulin is working. Carbo-loading before exercise to increase blood glucose will impair exercise performance and so normal intake with reduction in insulin is more effective both in preventing hyperglycaemia and hypoglycaemia. Taking rapidly absorbed carbohydrate in the form of a sport drink will provide the energy needed as well as the fluid intake required (Gallen 2005). People are advised to discuss this fine-tuning of their self-management with the healthcare team prior to undertaking exercise.

To achieve optimal self-management, the individual should use blood glucose monitoring prior to exercise, immediately afterwards and for several hours thereafter. If a person’s blood glucose is above 17 mmol/L, they should avoid exercise, especially if they also have ketosis (Frier 1999, page 278). On the basis of these results and by a system of trial and error, people can learn by how much their insulin should be altered in response to differing amounts of exercise. The prevention of exercise-induced hypoglycaemia partly depends on the type of exercise, its frequency and intensity.

People’s perception of exercise varies markedly. A person who frequently walks his or her children to school might be very active but does not consider this as exercise, whereas a person who works out on an exercise bicycle at home for 10 minutes might believe that he or she is taking sufficient exercise. It is important to determine each individual person’s normal lifestyle so that advice can be tailored.

It should also be remembered that hypoglycaemia can occur several hours after exercise has ceased. Hence, the person who goes swimming is unlikely to become hypoglycaemic in the pool but is more likely to feel hypoglycaemic a few hours later and insulin may need to be reduced.

The intensity of the exercise will affect the rate at which hypoglycaemia develops. Thus walking might gradually reduce the blood glucose level, resulting in hypoglycaemia several hours later, whereas half an hour on a squash court will rapidly reduce a blood glucose level. People should be guided and advised regarding their own requirements on an individual basis.

It is recommended that if the individual has experienced a severe hypoglycaemic episode within the previous 24 hours then exercise should be avoided as the counter-regulatory hormone response to hypoglycaemia is reduced and the likelihood of hypoglycaemia would be increased (Gallen 2005). Further information regarding managing diabetes during exercise can be found at www.runsweet.com.

IDENTIFICATION

Everyone with diabetes is advised to carry some form of identification to inform others that they have diabetes. This may be a card, a Medical Alert bracelet or a similar locket. Most pharmaceutical companies produce identification cards and there are advertisements in the Balance magazine of Diabetes UK for these products.

The combination of smoking and diabetes has been shown to escalate coronary heart disease, arterial disease (UKPDS 1998) and renal disease (Biesenbach et al 1997). Hence, the person who smokes is at greater risk of having heart disease, a cerebrovascular accident or developing peripheral vascular disease. People might not be aware of the increased risks due to both conditions and every effort must be made to strongly encourage those who smoke to stop. Those people wishing to stop should be referred to the smoking cessation support in primary care or increasingly at local pharmacies. There are various methods recommended to help people stop smoking (SIGN 2001). These include the use of nicotine patches, group or individual counselling and hypnosis. A recent study showed that cigarette smokers with diabetes had poor awareness, knowledge and uptake of smoking cessation treatments and concluded that this is a neglected area of diabetes education (Gill et al 2005).

STRESS

Stress, both physical and psychological, can have adverse effects on an individual’s blood glucose levels. This is important because suboptimal glycaemic control can be a symptom of stress and diabetes education would include assessment as to whether there were physical or emotional barriers to self-management. This holistic approach to care views the individual as a whole person and not just the sum of the parts (see Chapter 3).

ALCOHOL

Healthy drinking limits are the same for all whether or not they have diabetes. The recommended limits are 14 units of alcohol per week for women and 21 units of alcohol per week for men. People who are trying to lose weight should restrict their alcohol intake further (see Chapter 6). Alcohol taken with food seldom causes problems unless drunk to excess. When excessive alcohol is taken, hypoglycaemia can result. Others might wrongly assume that the person is drunk and not appreciate that the person needs glucose. People should be advised not to drink on an empty stomach but to consume food as well. Specific guidance is required for those who are trying to follow a calorie-restricted diet, and they should be referred to the dietician for this (see Chapter 6). It is difficult to manage diabetes if the person concerned has problems with excessive alcohol intake. People should be advised that there might be a greater lowering of their blood glucose if they undertake exercise after consuming alcohol (SIGN 2001). Both sulphonylureas and insulin can cause profound hypoglycaemia in the presence of excess alcohol. Under these circumstances, relaxing of glycaemic control is necessary if there is concern about excessive alcohol intake. The person should be encouraged to eat while drinking alcohol and to consume a carbohydrate-rich snack before going to bed.

DRIVING

A recent, large, multicentre study showed that people with type 1 diabetes were more likely to have driving mishaps due to hypoglycaemia than people with type 2 diabetes. However, it was found that half of those with type 1 diabetes and three-quarters of those with type 2 diabetes had never discussed hypoglycaemia and driving with their physicians (Cox et al 2003). This is clearly an important and neglected area of diabetes education.

In the UK, only those on oral hypoglycaemic agents or insulin therapy are required to inform the Driving and Vehicle Licensing Authority (DVLA). The responsibility for informing the DVLA lies with the individual. The primary healthcare team must ensure that the person is aware of this obligation. Once the DVLA has been informed then those on insulin therapy have a driving licence that is issued for 3 years and renewed at 3-yearly intervals thereafter, provided there is a satisfactory medical report. Those on oral hypoglycaemic agents will be given information and invited to inform the DVLA if there is any change in their treatment. They must also inform the DVLA if there is any other diabetes-related reason that might impair their ability to drive, i.e. diabetic eye disease. Once the person reaches 70 years of age the driving licence is renewed annually subject to a satisfactory medical report. This report is usually obtained from the GP or hospital specialist.

By contrast, in Northern Ireland the regulations state that every person with diabetes must inform the DVLA for Northern Ireland, regardless of their treatment. It is anticipated that this will change in the near future and will be brought into line with the DVLA in the rest of the UK. Those people who are controlled by diet or diet and tablets are issued with a licence for 10 years. Those individuals requiring insulin are issued with a licence for 1–3 years (Deegan 1995).

The great risk to the person and others is of hypoglycaemia while driving. For this reason, people who are taking a sulphonylurea or insulin are usually prohibited from driving any form of public service transport or heavy goods vehicle. Indeed, it is currently against the law for a Large Goods Vehicle licence or a Passenger Carrying Vehicle licence to be issued to a person requiring insulin therapy. As the UK becomes more involved in the European Union, this discretionary basis is likely to disappear. Helpful details can be downloaded from the Diabetes UK website (www.diabetes.org.uk).

Prevention of hypoglycaemia when driving is paramount. Any journey must be planned, especially a long journey. A blood glucose measurement must be taken before commencing any journey and carbohydrate consumed if below 5 mmol/L as driving becomes impaired when blood glucose is at 3.6 mmol/L (Cox et al 2003). Thereafter, blood glucose should be monitored at intervals on long journeys. A journey should not be undertaken when the person has injected insulin without having eaten. The person must allow for stops for food and to monitor blood glucose levels every 2 hours. Both rapidly absorbed carbohydrate and more substantial carbohydrate should be kept in a car in case of breakdown or delays in traffic, which could cause circumstances leading to hypoglycaemia.

Glucose must be kept in the car within easy access. If the person should feel hypoglycaemic, he or she should stop the car (using the hard shoulder on a motorway if needs be), switch off the engine, get out of the driver’s seat and take glucose to correct the hypoglycaemia. All this is required because the person could legally be charged with being in control of a vehicle while under the influence of drugs (Frier 1999). It is recommended that the journey is not resumed until 45 minutes after the hypoglycaemic episode so that cognitive function is fully resumed (Frier 1999).

All people with diabetes who are drivers should be advised to have their eyesight checked regularly and not to drive if their vision deteriorates suddenly or if their visual acuity with glasses is less than 6/12 in both eyes. Any eyesight changes must be notified to the DVLA.

EMPLOYMENT

It is illegal for employers to discriminate against people with diabetes except when there is substantial risk. Therefore people who are in employment are strongly advised to inform their employer of their diabetes. For those who have type 2 diabetes treated with diet and/or metformin there is not usually any problem with this. People who have type 1 diabetes or type 2 diabetes on sulphonylureas or insulin may find that certain aspects of their job are restricted because of the risk of hypoglycaemia.

There are, however, some forms of employment which are prohibited to any person who has type 1 diabetes (Box 11.7). Diabetes UK has lobbied hard to reduce the use of a ‘blanket ban’ on recruitment and is pressing hard for individual assessment (Diabetes UK 2005). Any employment where hypoglycaemia might not only endanger the life of the individual but also the lives of others is either prohibited or will require careful individual assessment. Those people who are currently employed in jobs that are classed as high risk and who then acquire type 1 diabetes might be allowed to continue in employment but in a less demanding post. Some forms of employment could be considered as inadvisable for a person with type 1 diabetes to pursue, again because of the risk of hypoglycaemia (Box 11.7).

Prohibited and inadvisable employment

Occupations prohibited to people with type 1 diabetes

▪ Airline pilot

▪ Train driver or working track-side

▪ Armed forces

▪ A job that needs a large goods vehicle (over 7.5 tonnes) or any large passenger-carrying licence

▪ Cab or taxi licences: some local authorities still operate a blanket ban

Types of occupation that would be inadvisable for people with type 1 diabetes

▪ Deep-sea diver

▪ Steeplejack

▪ Blast furnaceman

While it is possible for people with type 1 diabetes to undertake shift work, they will need advice regarding insulin doses and the balancing of food intake to accommodate this. Where this is relevant, the person would be advised to visit his or her diabetes specialist nurse for detailed, personal advice.

Diabetes is a condition for which a person can register as disabled within the UK. However, people should be warned of the employment consequences of being thus labelled. They should also be advised that, once registered as disabled, they cannot request removal from the register at a later date. The Disability Discrimination Act (1995) introduced new laws to reduce discrimination against disabled people and this should help people with diabetes seeking some types of work from which they were previously excluded, such as in the emergency services. For further information see the Diabetes UK website (www.diabetes.org.uk).

BENEFITS

As mentioned earlier, those people whose diabetes is controlled by the use of oral hypoglycaemic agents or insulin are eligible for prescription exemption within the UK. Previously, individuals controlled by diet were also exempt but this is no longer the case as the ‘diabetic diet’ is now regarded as healthy eating and not a ‘special diet’ (see Chapter 6). To apply for prescription exemption, the person must complete a FP92A form, which is available from the local social security office, some GP surgeries and local pharmacists. The person’s GP, who is required to complete part of the form, will then send it to the Family Health Services Authority (FHSA). The FHSA issues the exemption certificate and on its presentation, the person has exemption from paying for any items which are available on prescription. Prescription exemption can make a financial saving for those individuals who have multiple comorbidities requiring several different medications.

There are other benefits to which people with diabetes may be entitled within the UK. Further advice can be obtained by contacting the local Citizens’ Advice Bureau, the welfare rights adviser or social services department. Although several social security benefits are available, not everyone with diabetes is eligible for them. All people with diabetes are eligible for a free NHS eye test. However, only those on a low income are eligible for NHS vouchers for glasses. All these areas of policy are subject to change and if required the Citizens’ Advice Bureau webpage and advice guide can be consulted (www.citizensadvice.org.uk, www.adviceguide.org.uk).

People should be advised to inform all the insurance companies from which they have relevant policies once they are diagnosed as having diabetes. The responsibility for informing the various companies rests with the individual; this includes driving insurance. Failure to do so might jeopardise future claims. Some companies confer an additional premium for people with diabetes. The Disability Discrimination Act (1995) has not led to a reduced premium for life assurance or health-related policies as there is proof of higher risk for people with certain conditions, including diabetes. It is therefore important to shop around and receive quotations from several different companies. Diabetes UK has special arrangements with various insurance companies for people with diabetes. Advice can be given on motor insurance, life assurance and travel insurance. People should be encouraged to contact their regional Diabetes UK office for further information.

DIABETES UK

Diabetes UK, formerly known as the British Diabetic Association, is a charitable organisation, set up in 1934 by Dr R D Lawrence and the author H G Wells, both of whom had diabetes. Diabetes UK was the first patient organisation in the UK and promotes quality care for people with diabetes through campaigning, providing information, support and also funding research. It has an Advisory Council of people with diabetes and healthcare professionals to provide guidance on policy and care issues. Under the auspices of Diabetes UK, there are over 400 active local groups which are run entirely by volunteers. These groups offer support and companionship to people with diabetes and their carers. There are also a number of support events, such as adult and family weekends, children’s holidays and diabetes for life conferences throughout the UK. In addition, there is a network of regional offices to support and promote the work of Diabetes UK at a regional and national level across the UK. A careline (0845 1202 8960) is also available for professionals and people who wish to seek support and advice.

Those who join Diabetes UK receive a copy of Balance magazine bimonthly, updates on local or UK work and information on local Diabetes UK groups. The Balance magazine is for people with diabetes and is a welcome resource on current issues in diabetes management. Voluntary groups play an important part in caring for people with diabetes and people should be encouraged to link up with their local group.

For the healthcare professional, Diabetes UK is a valuable resource centre, which offers help and advice on a wide variety of topics. Healthcare professionals also have the opportunity to join Diabetes UK, which offers information and supplies professional journals.

Females

Some women with type 1 diabetes might require an alteration in insulin requirement around the time of menstruation (Steel 1991); some find that they require an increase in the insulin dose for a few days whereas others need to decrease the dose. Each woman has to be considered individually. Women with optimal glycaemic control have similar fertility to non-diabetic women. Hence, it is important that contraceptive advice is offered. Ideally, optimal glucose control should be achieved before conception and most women of child-bearing age should be encouraged to self-refer if they are considering pregnancy.

All forms of contraception currently available can be used by women with diabetes. The combined oral contraceptive pill is acceptable, especially with lower doses of oestrogen (Price 2003). Mechanical devices, intrauterine devices, caps and condoms have a fairly high failure rate, unless they are used very carefully, within the population as a whole. They are therefore not recommended where pregnancy is contraindicated. The intrauterine device was initially thought to increase pelvic inflammatory disease but this concern has now been resolved (Price 2003). Sterilisation is a suitable method of contraception for both men and women with diabetes once they are sure that their families are completed.

Planning for pregnancy is of vital importance for a healthy outcome of both mother and baby. Suboptimal glycaemic control at the time of conception and during the first trimester is associated with an increased risk of fetal malformation and mortality (Girling & Dornhorst 2003). It is, therefore, important that all women of childbearing age are made aware of this fact and encouraged to achieve optimal glycaemic control before stopping contraception. The majority of women of child-bearing age with diabetes will have type 1 diabetes, although there are an increasing number of women with type 2 diabetes now becoming pregnant as the age of those diagnosed with type 2 diabetes continues to decrease. Those people on oral hypoglycaemic agents should be changed to insulin regimens prior to conception.

Hormone Replacement Therapy is suitable for women requiring symptomatic relief.

Males

Erectile dysfunction (ED) is usually under-reported by men with diabetes. The causes are multifactorial (see Chapter 9). Erectile dysfunction that is due to psychogenic causes might respond to psychosexual counselling. Men with diabetes should be informed of this potential complication and encouraged to report it if it is present and causing problems. The treatment options for those with erectile dysfunction have increased greatly over the last 10 years and include oral treatments such as phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE 5) inhibitors such as sildenafil (Viagra), intracavernosal injection therapy, transurethral administration of a vasoactive agent (e.g. alprostadil) (MUSE) and vacuum therapy. For a minority of men, surgery might also be required. Price (2003) suggests considerable advantages to erectile dysfunction being treated in primary care and, as no specialised equipment is required, there is no reason why GPs with an interest in diabetes and the management of erectile dysfunction should not effectively treat the majority of men with this problem.

DIABETES AND TRAVEL

Samantha is a 32-year-old woman who was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes at the age of 23. Since diagnosis she has maintained excellent control and is very meticulous about her diabetes care. She is married with two children and is planning a foreign holiday this year with her husband and family. This is her first holiday abroad and she is worried about how she will maintain control of her diabetes as she is flying to New York and so will enter a new time zone.