THE PROBLEM

It is unusual for a government with a majority in both houses of the Federal Parliament to have legislation temporarily abandoned after consideration by a standing committee of the Australian Senate. This chapter analyses policy in its development phase. Specifically, we examine the development of the Australian government’s proposed Access Card policy to the point where the enabling Bill reaches the upper house of the Australian Parliament, the first step in the legislative process.

The use of a public forum for discussion is an approach often used by governments to legitimise contentious new policies; we observe the tensions and conflicts that have become evident during this process and the ensuing problems that surround the Access Card policy. What you are about to read, therefore, describes ‘policy in progress’.

From a health perspective, our interest is the suggested use of the proposed Access Card as a repository for health information, and its relationship to an individual patient identifier (IPI). In its current embryonic form, the Access Card embodies a leading-edge technology with multiple functions and significant potential benefits for Australians. However, a policy to develop and implement impressive, state-of-the-art technology to reduce health and welfare benefits fraud is shifting and weaving because of different opinions embedded in societal values. Herein lies the problem: the ability of policy makers to respond to criticisms that the Access Card threatens cherished societal values. The tensions between the proposed Access Card and values is summarised in Table 11.1 (overleaf).

The primary stated purpose of the Access Card is not to hold personal health information; but rather, to be the central collection of individuals’ social and health benefits information. The card is designed to streamline the system, combat health and welfare benefits-related fraud, and militate against identity fraud, estimated at between $1 and $4 billion per annum (Department of Human Services [DHS] Office of the Access Card 2007a p 1). To this end, the Access Card is designed to hold a collection of the information contained in up to 17 existing, separate health and welfare benefits cards, including the Medicare and Centrelink cards (DHS Office of Access Card n.d., KPMG 2006). It is technically a ‘voluntary’ card; however, all who are eligible for, and who wish to access, a wide range of government services or to claim reimbursement for services under the national health insurance scheme will be required to have the card. Thus, it will be virtually a universal card held by almost all of the Australian population. It will not be compulsory for cardholders to carry or to show their card, other than for the stated health and welfare business purposes. The card is planned for introduction in 2010, with registration commencing in early 2008. A register, described as ‘a national population database’ (Australian Privacy Foundation 2007 p 4), will contain the government-related information unique to every cardholder. The government has assured Australians that the register will not be linked to taxation, health or medical records (DHS 2007). There is a proposal, however, for a document verification service to link key databases, including the states’ births, deaths and marriages registers, with the Commonwealth Department of Human Services, in an effort to prevent duplication and identity fraud.

The Access Card is being promoted by the Australian government as offering practical benefits to cardholders, viz: less time spent waiting in queues on health and welfare benefits-related business, reduced clutter in wallets because of the presence of one card in lieu of several, a standard form of identity across health and welfare agencies, the provision of additional security to protect against identity theft, and greater efficiency for users because a single card constitutes a ‘one-stop’ facility for amendments to demographic information such as change of address (DHS Office of Access Card 2007a).

THE ACCESS CARD POLICY DEVELOPMENTS

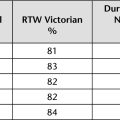

Key policy developments are summarised in Table 11.2 (overleaf). The concept of a smartcard for Australia’s health and welfare systems was raised by the Minister for Human Services in April 2005 (Hockey 2005 p 4). The state premiers were subsequently briefed by the Prime Minister (reported in Hockey 2006a p 3). In early 2006 the consultancy firm, KPMG, released a commissioned business case for the introduction of a national health and social services smartcard initiative, some sections of which were withheld from public release. This report mentioned only briefly that a computer chip in the card would store information in different zones with different levels of access and security, including optional organ donor status and personal health details (allergies, drug alert notifications and chronic diseases); the authors noted that this would in no way constitute a ‘clinical record’ (KPMG 2006 pp 37, 42, 45).

|

Table 11.2 Policy events surrounding the Access Card |

|

| Date | Policy event |

|---|---|

| 2005 (April) | Minister for Human Services raises concept of a smartcard for Australia’s health and welfare systems. |

| 2005 | Prime Minister briefs state premiers on the smartcard concept at the Conference of Australian Governments (COAG). |

| 2006 (February) | Release of commissioned KPMG business case for the introduction of a national health and social services smartcard. |

| 2006 (April) | Formal announcement of proposed smartcard (called the Access Card). |

| 2006 | Australian Government Department of Human Services. Strategic Plan 2006–07 includes implementation of the Access Card as the first objective. |

| 2006 (May) | Office of the Access Card established. |

| Minister for Human Services announces to the Australian Medical Association National Conference that the government would be open to the inclusion of medical/health information on the Access Card, to be determined and controlled by the cardholder. | |

| 2006 | Access Card Consumer and Privacy Taskforce established to facilitate community consultation and input. |

| 2006 (June) | Policy evaluation process begins: |

| Project funding announced: $1.09 billion over 4 years. | |

| Announcement that: | |

| Minister notes that the Access Card will have capacity for voluntary fields ‘… such as organ donor status, … blood type, … emergency contact information’ (Hockey 2006a p 7). | |

| 2007 (February) | Taskforce releases Discussion Paper Number 2 and invites further comment. |

| 2007 (February) | The Human Services (Enhanced Service Delivery) Bill 2007 introduced to the Parliament. |

| 2007 (February–March) | Australian Senate refers Bill to its Finance and Public Administration Standing Committee for inquiry into provisions regarding: |

| 2007 (15 March) | The Australian government temporarily abandons the Access Card legislation following the report of the Australian Senate’s Finance and Public Administration Standing Committee of Inquiry which recommends that the legislation be stalled until accompanying legislation containing privacy and other safeguards is drafted and considered simultaneously with the Human Services (Enhanced Service Delivery) Bill 2007 (i.e. the Access Card Bill). |

In April 2006 the Australian government formally announced the proposed Access Card (DHS Office of Access Card 2007b). Its implementation was embedded in national policy as the first objective in the Commonwealth Department of Human Services’ 2006–07 Strategic Plan (DHS 2006a). The Office of Access Card was established the following month (DHS Office of Access Card 2007b) and the Access Card Consumer and Privacy Taskforce created subsequently, to facilitate community consultation and input (DHS Access Card Consumer and Privacy Taskforce 2006 p 3). Project funding of $1.09 billion over 4 years was announced in the June (DHS Office of Access Card 2007b), with the Minister for Human Services predicting the project would entail ‘a massive logistical exercise’ (Hockey 2006a p 5). In November, the minister stated that the project had commenced in May; that is, prior to the release of discussion papers or provision for public debate (Hockey 2006c p 4).

From the outset, the primary purpose of the Access Card has been to operate as an administrative tool for fraud deterrence; concurrently, there have been persistent allusions in the media to its potential role as a national identification card; for example, in the wake of the London terrorist bombing (Prime Minister of Australia 2006). Then came a strong message of an early shift in policy: the government would most emphatically be open to extending the scope and role of the card by adding a personal medical information function, thereby creating a form of health record, albeit partial and fragmented:

Importantly for the medical profession, there will also be space available for cardholders to voluntarily include vital personal information that could be used in medical emergency such as next of kin, doctor details, allergies, drug alerts, chronic illnesses, organ donor status and childhood immunisation information.

Announcing this to doctors, at a national conference of the Australian Medical Association (AMA), was a positive tactic by the government. It deftly acknowledged the most visible stakeholders in health information systems; it made a definite shift in policy direction; it diverted attention, for a short while, from the national identity card issue by presenting the card as offering benefits to the cardholders’ health; and simultaneously it quietly condoned, through ‘function creep’, an important secondary function of the card. This facility was later extended to cardholders being ‘… able to add other information that you may wish to include’ (Hockey 2006c p 15). The minister stated that the key principle would be that ‘individuals will control the information that is on the card’ (Hockey 2006b p 7); this, he argued, was one of the ‘many reasons’ why the Access Card would not be a national identity card (Hockey 2006b p 7).

The Access Card was now well on its way: the government was appointing a project manager and tendering for legal, public relations and research services for the project; early decisions were planned on technological issues and there was to be a focus on selling the card to the public by explaining its ‘real’ benefits (Hockey 2006a p 11).

The taskforce released its initial discussion paper for public debate and consultation in June 2006. A second paper, of February 2007, reflected input from key stakeholders and others by responding to the concerns expressed in many submissions by representatives of civil rights, legal and privacy groups regarding the technical mechanisms for collecting and accessing personal medical and emergency information. The concept of a divided chip and the notion of a two-tier system for the cardholder’s personal health information were elaborated upon, and invitations made for further comment by interested parties.

The Human Services (Enhanced Service Delivery) Bill 2007, was introduced to the Australian Senate in February 2007. It was referred immediately to the Finance and Public Administration Standing Committee, no doubt partly in response to several high profile senators who called for an inquiry to address the concerns of organisations such as the AMA and the Australian Privacy Foundation. The Senate committee was briefed to inquire into the provisions surrounding the card’s scope and purpose, the information to be included in the card register and on the card’s chip and surface, and the range of offences for improper access to and use of the card (Senate 2007b). Extending the policy evaluation process effectively lengthened the period of public consultation.

Despite the emphasis on the positive health benefits of the Access Card’s extra health information, the notion has persisted of it being or becoming a national identity card. Widely reported disquiet amongst members of Parliament from all political parties has reflected these concerns (Australian Associated Press 2007).

The underpinning policy evolved to a proposal in February 2007 for three segments of information on the card (DHS Access Card Consumer and Privacy Taskforce 2007). The surface will show certain identifying information and a digital photograph. The card will hold a two-part electronic chip accessible only via an approved reader; the content of the first part will be determined and amended only by the Commonwealth. The second part, containing approximately 20kb of the 64kb chip, will be under the control of the card ‘owner’; two tiers are proposed for this part. The taskforce has suggested that the first tier should contain only information essential to facilitate emergency treatment in a crisis situation. Clearly, one immediate privacy concern is that it will be available to anybody with a reader, including those employed across the wider health and welfare sectors whose work responsibility does not include a legitimate interest in the cardholder’s health status or medical treatment. The taskforce recommends that the second tier be protected by a personal identification number (PIN), accessible only with the cardholder’s consent, and contain ‘other medical and health data’ (DHS Access Card Consumer and Privacy Taskforce 2007 p 5).

Population-based health identification of Australians

A consistent approach to indentifying individual members of the Australian population for healthcare-related purposes had been introduced previously through the Medicare Card, in the management of the national health insurance scheme. This identifier facilitates financial reimbursement for health services approved by the Australian government. However, its use is legally, albeit not practically, limited to financial re-imbursement because in practice it is also used for other identification purposes, such as establishing points to open a bank account.

The early policy statements specified that the Access Card could only be used for identification purposes relating to health and welfare benefits business or, ostensibly, in a medical emergency situation. However, the government appeared to have broadened its approach by December 2006 when it indicated that cardholders may use the card for ‘any lawful purpose, including using it for identification purposes, if they choose’ (DHS 2006c p 2). This statement conflicts with an earlier comment by the then minister (Senator Ian Campbell) that the card could not legally be used for identification, other than for health and welfare benefits business (Campbell 2007).

The Australian Privacy Foundation has expressed concern that the ‘invisible functionality’ of the register underpinning the Access Card scheme will support ‘data-matching, profiling and the creation of virtual “dossiers” on all Australians’ (Australian Privacy Foundation 2007 p 4). In replacing the Medicare Card, the Access Card is designed to assist in the unique identification of individuals, consistent with Australia’s e-health priority initiatives (National Electronic Health Transition Authority [NEHTA], 2007a). In order to appreciate the connection between personal health information and a government smartcard, it is useful to explore the concept of the electronic health record (EHR) and its policy environment.

SHARING HEALTH INFORMATION

The electronic health information infrastructure

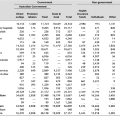

In recent years, there has been consistent national policy to support the introduction of electronic health records (EHRs) (refer to Table 11.3). One of the critical pre-requisites to the EHR infrastructure is a unique patient and/or client identifier.

|

Table 11.3 Summary of EHR-related policy |

|

| 1999 | National Health Information Management Advisory Council (NHIMAC) proposed initiatives to evaluate the potential for electronic health records in Australia in its discussion paper ‘Health Online: a health information action plan for Australia’. |

| 2000 | Health ministers provided joint funding for 2 years of research and development to assess the value and feasibility of HealthConnect (2006b). |

| 2004 | The National Health Information Management and Information and Communications Technology Strategy (Boston Consulting Group 2004) commissioned by the National Health Information Group (NHIG) and the Australian Health Information Council (AHIC). The strategy included a coordinated approach to the development of EHR infrastructure, including identification, between the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, Standards Australia, and the state health departments. |

| 2004 (July) | National E–Health Transition Authority (NEHTA) established by the Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council (AHMAC). |

HealthConnect is the overarching, collaborative, Australia-wide strategy for adopting common standards for electronic systems to enable the secure exchange of health information between healthcare providers and organisations; its primary aim is to improve service delivery by enhancing continuity of care through access to shared EHRs. The scope of health data to be provided and the vehicles for information flow have generated much discussion and have yet to be defined. The privacy and security of health information and the timeliness of the information flows are prime considerations.

There have been several trials, ranging from patient-held smart cards to regional shared databases, in which clinical information was communicated between different types of providers as the patient moved through the healthcare system. Importantly, the trials have highlighted the need for ‘a foolproof system of identification’ of individual members of the population in order to prevent errors in information systems and people receiving incorrect treatments (Department of Health and Ageing 2006; HealthConnect 2005). The need for both the verification and the coordination of the identification of individuals is central to the concept of electronic health records.

The National Health Information Management and Information and Communications Technology Strategy (Boston Consulting Group 2004) concluded that the development of an EHR infrastructure, including identification, required a coordinated approach between the main governance organisations, that is, the Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing, Standards Australia and the state and territory health departments.

The National E-Health Transition Authority (NEHTA) was established by the Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council (AHMAC) in 2004 with a brief to develop better ways of electronically collecting and securely exchanging health information. NEHTA has a commitment to several priority initiatives funded by all governments, including secure identity management through Digital Identity Management (DidM) approaches and a national health identifiers project. It is responsible for the development of a privacy blueprint for electronic health information, including the Unique Healthcare Identifier (UHI) (NEHTA 2006a, 2007a, 2007b); the implementation strategy for a national UHI is still being developed.

To date, NEHTA has identified existing and recommended national standards for use in a national e-health infrastructure, including a key standard: Health Care Client Identification (Standards Australia 2006). NEHTA is also supportive of relevant international health informatics standards: the international standard on identification of individuals in healthcare, for example, includes the use of biometric identifiers as a mechanism for overcoming identity theft (International Standards Organization 2007). In contrast, the current plan for the Access Card is a photographic identification, which is less accurate and less useful in preventing identity fraud; moreover, the photograph will need to be updated about every 10 years.

The states and territories and the identifier problem

The state and territory governments are separately developing e-health infrastructures, adopting national standards developed or advocated by NEHTA, and creating links between providers (HealthConnect 2006a). Developments underway include the use of electronic messaging to send prescriptions for medication from a doctor to a pharmacy, electronic referrals and requests sent between healthcare professionals, and electronic hospital discharge summaries sent from the hospital to the patient’s doctor or aged care facility (HealthConnect 2006b).

The initiatives in electronic health information systems undertaken by the state and territory health authorities reflect the need for unique identification to support two critical functions: (i) safe and accurate sharing of health information; and (ii) providing population-based health information that can better inform health service planning, health outcome monitoring, and identifying trends in public health. Each state health authority needs a solution to the identifier problem. The fact that some are progressing faster than others, or were initially in advance of national initiatives, has resulted in a raft of different approaches to the problem.

Current policy on patient identifiers

The data items planned for the Access Card do not meet the technical requirements for identification in healthcare, per the national standard (Standards Australia 2003). Nor is there any indication of how the Access Card would handle the need for the cardholders’ names to be linked to specific healthcare services; this is exemplified in the Aboriginal community where individuals may have one name used within the tribal context and another for communication with outside or government agencies. There are further requirements special to healthcare records, such as the recognition of people’s preferred names. These problems reflect the complexities inherent in designing for proper patient identification for health information and electronic health records.

The taskforce indicated in early 2007 that it does not favour the development of a quasi-EHR without appropriate controls or standardisation (DHS Access Card Consumer and Privacy Taskforce 2007 p 9). It notes also that the work of NEHTA and other agencies is not related to the Access Card program (DHS Access Card Consumer and Privacy Taskforce 2007 p 10). NEHTA is coordinating the national-level activities associated with patient identifiers for healthcare and, thus far, has not stated its policy position on the use of the Access Card for the unique identification of members of the Australian population for health information purposes. However, the Access Card’s failure to meet the national standard for healthcare identification would make it an unlikely candidate for holding a UHI. The absence of government policy in this regard raises further privacy and access concerns, relating to function creep, that have beset the Access Card. In essence, as NEHTA is still developing an implementation strategy for the UHI, an early statement of the intent, or otherwise, to use ‘generic’ cards such as the Access Card to support NEHTA’s initiatives would be beneficial. The Australian Privacy Foundation’s concerns about the ‘lifelong unique ID number to be held in the underlying database’ (Australian Privacy Foundation 2007 p 6) highlight the need for clear differentiation between this and the Access Card number, and the potential uses for data-matching.

The key problems

In examining the policies underpinning the Access Card as a potential personal health record, it is important to contextualise the proposed health information component within the government’s wider policy objectives for the card. It is evident, when we divert momentarily to the broader framework of the Access Card, that there are tensions throughout the Australian society that reflect widespread unease and, indeed, dissatisfaction with the policy underpinning the card. These can be observed in the media coverage and the submissions to the taskforce and the Senate Inquiry, and have generated some policy shifts in the lead up to the release of the draft legislation.

Duplication and conflict with parallel smart card developments

There have been several trials of smart cards used as EHRs and the duplication of information of these true health records, in addition to the fragmented information on the Access Card, may create confusion when one record is more up to date or two records conflict, for example, concerning medications. This is exemplified in the coordinated care project, run by Southern Health in Victoria, which trialled a card for information sharing; the card was neither well received nor well used. The difficulty of ensuring that material on a card is up to date was identified as a major patient safety issue (HealthConnect 2005). It is for these reasons and others that the NEHTA approach to alert and allergy information is based on the ability of care providers to share information of this type in a consistent manner and to verify the information (NEHTA 2006b).

The predominance of the technological solution

This perspective includes views of technological determinism, wherein the Australian government is seen to be implementing a novel technology with insufficient recognition of its potential impact on social values and preferences. An indication of the magnitude of this project can be seen in the Australian Computer Society’s assessment that the Access Card:

will be one of the largest ICT (information and communications technology) projects undertaken by the Australian Government and has the potential to have a significant impact on the Australian ICT landscape and industry sector.

The Access Card as a national identity card

This view reflects the emergence of the Access Card as a national identity card with inherent characteristics of Orwellian-type surveillance by government and concomitant threats to personal privacy. Liberty Victoria, for example, is one of many organisations that have equated it to a national identity card (Pearce 2007 p 15). There have been well-substantiated claims that it is potentially more problematic, in terms of threats to Australians’ civil liberties, than the failed Australia Card proposed by a previous government in the 1980s, and that it will create an ‘unprecedented identity database’ in Australia (e.g. New South Wales Council for Civil Liberties 2006 p 1). The government has stated categorically that the intent of the legislation is to ‘… ensure that the Access Card is: not a national identity card; not required to be carried at all times; and not able to be demanded outside health and social service purposes’ (DHS 2006). Based on evidence of the submissions to the taskforce and the Senate Inquiry, it is reasonable to conclude that, despite government assurances and efforts to address concerns in the wider community, the privacy and legal rights of future cardholders remain substantial problems; these necessarily impact upon the health record components of the Access Card.

Function creep

The card has already been slated for purposes beyond the administrative amalgamation of social and health benefits eligibility. The AMA has observed that the health information function is connected to current and future Australian EHR developments and electronic patient medication records (AMA 2006). The provision of a facility on the Access Card for people to record personal health information is secondary to the main game, specifically to the EHRs of the future; as the AMA succinctly put it: ‘The benefits do not link to the primary purpose’ of the Access Card (AMA 2006 p 2). In fact, the anomaly remains that the administrative benefits data on the proposed Access Card and any form of personal health information are quite different pieces of information with no apparent logical inter-connection.

The costs of the project

The evidence also shows that the projected capital and operating costs of the project are an issue of public concern, the reasons being the size of the required capital investment, the significant risks associated with such a highly complex project, and the perceived lack of strategic planning for project and risk management (Australian Computer Society 2006 p 2, NSW Council for Civil Liberties Inc 2006 p 14). The initial costing of $1.09 billion for the first 4 years excludes the ‘optional extras’ that have resulted from the policy shifts, such as the provision of a space for cardholders to add health information. Nor does the costing account for the problems that inevitably beset all major information technology projects.

Access

Rights to access are inconsistent with individuals’ practical needs: the Medicare Card is accessible to those aged 16 years and over, but a special application is required for the Access Card for those aged 16 and 17 years (AMA 2007 p 3).

Ownership

The blurring of principles surrounding card ‘ownership’ and the ‘control’ of its information is problematic; for example, according to the Bill the cardholder is the ‘owner’, but they do not own certain information on the card (AMA 2007 p 3).

The use of taxpayers’ money to fund the project

It has been estimated that the cost of the project will be offset by savings of up to $3 million over 10 years from reduced health and social service benefits fraud (KPMG 2006). Notwithstanding this, concerns have been raised about government moneys being used to fund the development and implementation of this technology and its supporting infrastructure, the technical development benefits of which will subsequently be taken up by the private sector. For example, the Australian banks have not yet adopted this level of smart card technology and, along with other commercial businesses, will reap the benefits of this major government investment (NSW Council for Civil Liberties 2006 pp 14–15, Dearne 2007). However, the converse might be argued; that is, that the precedent of the US National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA) massive capital intensive developments have flowed to the private sector, representing a positive model of government enterprise in funding the development of technological and related cutting-edge products for the greater societal good.

When is a health record not a health record?

The government’s clearly stated policy in June 2006 was that the Access Card would not constitute ‘… an electronic health record, that is, it will not contain extensive clinical health information’ (DHS Access Card Consumer and Privacy Taskforce 2006 p 8). This begs the question of what is a health (or medical) record and how much health information needs to be assembled in any one place in order to constitute one. Health records, in fact, come in various guises and sizes. It has been long-established that the physical (paper or electronic) health record ‘stores the knowledge concerning the patient and his care’ (Huffman 1981). Health records ideally are complete and comprehensive, although some are sparse or fragmented, depending upon the setting, the extent and nature of care and treatment provided, and the recording media. In this interpretation, the record is a cumulative and sometimes multi-part electronic or paper document or a combination thereof (hybrid). Some parts are small (a single blood test result) or are awaiting incorporation in the main record (a recently reported test result). Any medical or demographic information that is placed on the Access Card would constitute a form of personal health record; for example, disease status alerts (diabetes, epilepsy); organ transplant status; allergic reactions (such as to penicillin or other drugs, or to latex); current medication and prescription details; or the name and contact details of next of kin.

Benefits and disbenefits: Access Card health information

The option for cardholders to add health information to their Access Card has many potential medical benefits. Record linkages are being suggested: the taskforce recommends the inclusion of register database information (e.g. organ donation, childhood immunisations) and linkage between the Access Card and the Medic Alert register (DHS Access Card Consumer and Privacy Taskforce 2007 p 10). There are, however, inherent privacy problems surrounding any health database linkage.

Simple alerts are potentially useful as early information to doctors and other health professionals in emergency situations; however, it is inevitable that many people will be reticent about including what they perceive as sensitive health information on a card that can be read by anybody who has a reader to access the health information section of the card. The most obvious of these might include: people on methadone treatment; current or former intravenous drug users; those with HIV; and those with sexually transmitted and other diseases or infections which they do not wish to divulge to anybody other than their treating doctor.

Genuine alert information can be useful; ostensibly, advance directives by people who, for religious or other reasons, do not wish to receive a blood transfusion are helpful to these individuals and healthcare providers. However, the converse view, expressed by the Australian Medical Alert Foundation, is that the inclusion of critical personal health information on the Access Card could provide the cardholder with a false sense of security (Australian Medical Alert Foundation 2006 p 1).

A robust system of verification and authentication by doctors and pharmacists is essential for health professionals to use it confidently in an emergency situation (DHS Access Card Consumer and Privacy Taskforce 2007 pp 4–5). Health information that is selectively included could, if relied upon by treating health professionals, present problems, for example for doctors in prescribing medications and avoiding potential drug interactions, and in prescribing drugs of addiction. These issues arguably will present medico–legal and clinical problems for emergency department doctors who may need to assume that, failing a highly efficient and comprehensive updating and verification system, information provided on the Access Card is inherently incomplete, out of date or, possibly, incorrect. The usual clinical protocols will still need be followed in taking histories, conducting physical examinations, making clinical assessments, forming diagnoses, and in determining and administering treatments (Dr D C Robinson, personal communication). In other words, the current checks and balances will need to be kept in place regardless of the information on the Access Card; for instance, if a patient has their blood group included on the Access Card, safe clinical practice dictates that this be cross-matched prior to a transfusion. The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) has expressed concern about the medico–legal ramifications of health professionals acting upon out-of-date information on the Access Card and suggests the inclusion only of information that does not change over time, such as blood type (RACGP 2006).

There are other potential problems with patient-selected health information in fragmented health records such as the proposed Access Card. People can be labelled, or labelled incorrectly, when previous diagnoses are assumed on the basis of the listed medications. It would be extremely useful for treating staff to know about many types of conditions where a patient can rapidly deteriorate and become unconscious or unable to communicate; it is likely that some people will include these on the Access Card (e.g. Type I diabetes, epilepsy, haemophilia, asthma). Similarly, the inclusion of rare conditions such as specific cancers (e.g. the type of lymphoma or leukaemia) would be helpful to doctors and, subsequently, patients in emergency departments and other places, as would knowledge of conditions such as dementia (Dr D C Robinson, personal communication).

Diffusion of the Access Card will be complex, expensive and time-consuming. Dedicated card-readers will need to be distributed to every ambulance, emergency department, clinic, private medical practice and pharmacy, as well as every branch of government welfare and health services in the country. It remains to be seen whether a typical ambulance paramedic will have time to search the pockets of a comatose patient to find the Access Card and then scan it via the reader, prior to commencing emergency assessment and treatment.

The threshold question

Public submissions to the taskforce and the Senate Inquiry have generally supported the principle that specific emergency health information should be included on the Access Card (DHS Access Card Consumer and Privacy Taskforce 2007 p 4). The Taskforce identifies the ‘threshold question’: What information is absolutely necessary in a crisis situation and what is ‘merely convenient’ for the cardholder to have stored on the card?

The taskforce has stated that it would be impractical to provide for over-riding of the PIN access in its two-tier system, even in emergency situations. It further suggests that doctors (medical information) or pharmacists (medication prescription and dispensing details) must verify and authorise (via a hard copy form) the information entered on the card, and that this be done only at an approved location (DHS Access Card Consumer and Privacy Taskforce 2007 p 8).

Australians would have the right, therefore, to their own little piece of digital real estate on which they can place the health problems they deem to be important enough to have future healthcare providers read, but only via a special reader and PIN. This is likely to create an onerous administrative burden for the public and private healthcare sectors as doctors, pharmacists and healthcare facilities and services would have to manage the additional checking and verification work, which will present inherent and ongoing major management, legal and cost problems.

Future policy directions

The policy supporting the inclusion of health information, selected according to the individual’s preferences, has been shaped by responses and submissions from key stakeholders during the months leading up to the Senate Inquiry. It seems evident that several critical issues differentiate healthcare identification and will keep the issue of health information and health identifiers ‘alive’ in a policy sense. They include:

- the superior privacy requirements for health information

- the specific identifier requirements in healthcare and health information

- the situation whereby NEHTA is trying to develop appropriate identifier-related initiatives according to rigorous standards, while the world moves around them

- the pragmatic need of the states and territories to progress their own EHR developments before NEHTA has completed its design and development, thus creating a ‘messy’, uncoordinated approach

- the federated model of Australian healthcare which militates against the development and use of common EHR systems, given that general practice is governed nationally and many other services and providers are governed through the states and territories

- the unknown future uptake of the NEHTA UHI

- the safety of clinical information on the Access Card, given the need for it to be up to date, accurate and entered in a timely manner

- the international standards on biometric identifiers in healthcare and health information.

- the specific identifier requirements in healthcare and health information

In the current policy environment, an extreme view would be that the attempt to include health information on the Access Card could be an effort by the Australian government to ‘test the water’ regarding the response of the Australian public to the introduction of a unique identifier for each member of the population, as a precursor to the future introduction of EHRs. This could be extrapolated to incorporate unwelcome surveillance through a national identity card that links health and welfare benefits, Medicare and related eligibility and financial claims, and key details of the individual’s personal health record.

The status of the legislation

The Australian government temporarily abandoned the Access Card legislation on 15 March 2007, subsequent to the findings of the inquiry by the Australian Senate’s Finance and Public Administration Committee (Senate 2007a). The Senate Committee recommended that additional legislation containing safeguards (e.g. relating to privacy and other problems) be drafted for consideration simultaneously with the original Bill at a future date.

The Australian Labor Party Senators on the committee concurred with the substance of the decision and expressed their concerns about unresolved key issues (Senate 2007c). Similarly, the Australian Democrats, in indicating their concerns with a raft of aspects including the privacy, consent, and potential record linkage facilities of the draft legislation, descried the inherent function creep and overall lack of safeguards in the Bill (Senate 2007d).

CONCLUDING OBSERVATIONS

Records are ‘central to the administration of complex environments’ (Iedema 2003 p 152) which necessarily include health and social benefits administration, and medical care and treatment. They constitute ‘… the information base of the modern state and of the modern organization’ (Iedema 2003 p 151). The administrative power generated by the nation-state could not exist without the information base that is the means of its reflexive self-regulation (Giddens 1985 p 180). Indeed, the importance of health records cannot be underestimated, and nor can their significance to governments, the healthcare industry, health professionals, and the individual subject of the record. The Access Card, as a form of health record, will contain information of fundamental importance to the state and individual cardholders. The dilemma for the Australian government lies in achieving a balance between using up-to-date technology to reduce benefits fraud, and accommodating cardholders’ wishes for personal privacy, confidentiality and protection from unreasonable surveillance by the state.