CASE 11 Chronic Total Occlusion Intervention

Cardiac catheterization

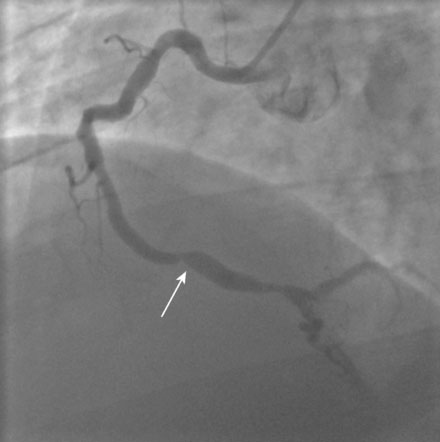

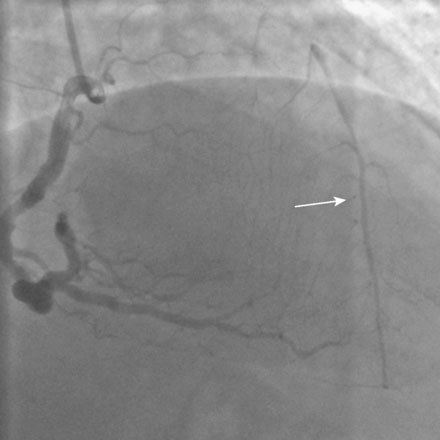

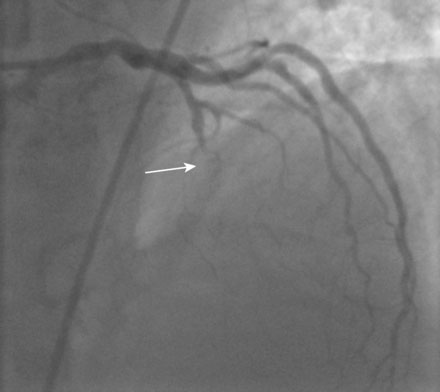

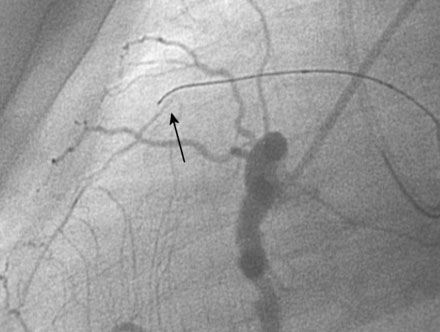

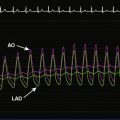

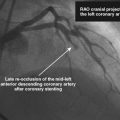

The left ventriculogram was normal, with an ejection fraction of 60% and no segmental wall motion abnormalities. A severe stenosis was noted in the right coronary artery (Figure 11-1). There was also a prominent collateral vessel to the left anterior descending (LAD) artery (Figure 11-2 and Video 11-1). As was suspected because of the presence of collateral circulation from the right coronary artery, there was total occlusion of the LAD. The circumflex artery appeared free of significant narrowing (Figures 11-3, 11-4 and Video 11-2). Although the right coronary lesion appeared readily amenable to percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), the angiographic appearance and clinical history suggested that the LAD occlusion was likely chronic and might not be successfully treated percutaneously. The physician decided to terminate the procedure and discuss therapeutic options in more detail with the patient.

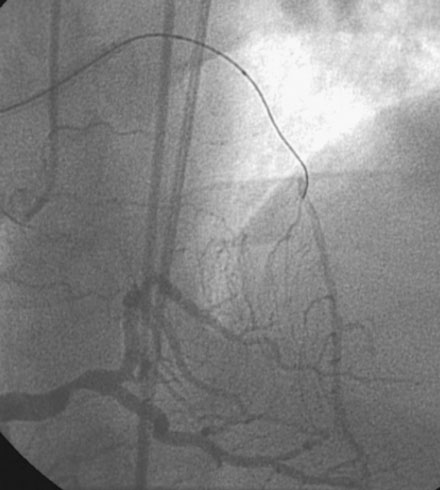

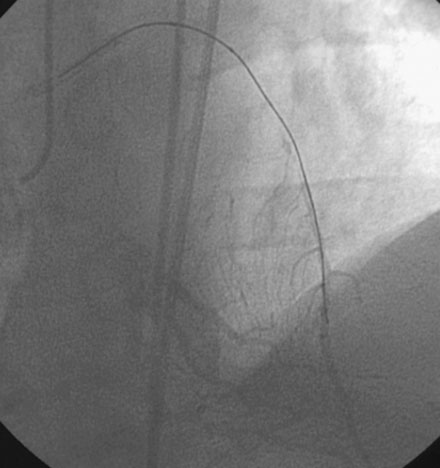

The patient returned to the cardiac catheterization laboratory. The operator decided to use the prominent collateral to the LAD from the right coronary artery to help guide attempts at crossing the occluded segment. Therefore, two angiographic manifolds were prepared and femoral arterial access obtained from both the right and left femoral arteries. After engaging the right coronary artery with a diagnostic catheter and the left coronary artery with a guide catheter, contrast was injected first in the right coronary artery and then in the left coronary to define the extent of the LAD occlusion (Figure 11-5 and Video 11-3).

FIGURE 11-5 Simultaneous injection of the right and left coronary arteries shows the extent of the occlusion (arrows).

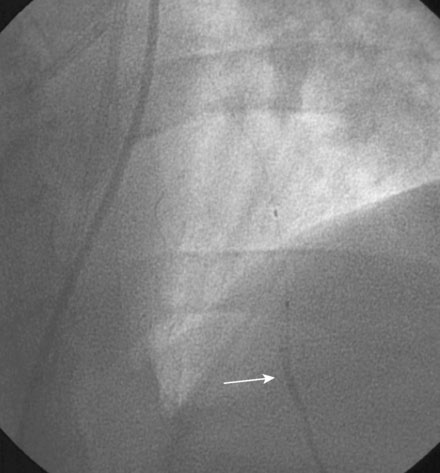

Unfractionated heparin was administered as a bolus to achieve a therapeutic activated clotting time; clopidogrel had not been given prior to the procedure in the event that PCI was unsuccessful and bypass surgery was required. The operator chose a tapered tip guidewire specifically designed for chronic total occlusions (Asahi Miracle Bros 3.0) and loaded this wire into a 2.0 mm diameter by 20 mm long “over-the-wire” compliant balloon. In the right anterior oblique projection, the operator advanced the stiff-tipped guidewire through the occluded segment, using occasional injections into the right coronary artery to visualize the collateral. Eventually, it appeared that the wire had advanced all the way through the occlusion (Figure 11-6 and Video 11-4). Angiography of the wire and collateral in the lateral projection, however, demonstrated that the wire tip was parallel to the artery and not in the true lumen of the LAD (Figure 11-7 and Video 11-5). The wire was gently withdrawn and repositioned, ultimately achieving the distal lumen of the LAD (Figure 11-8 and Video 11-6). The balloon easily advanced through the occlusion but, prior to inflation, the operator removed the guidewire and gently injected contrast through the balloon lumen to confirm location within the true lumen of the distal LAD (Figure 11-9 and Video 11-7). A floppy-tipped, 0.014 inch guidewire was reinserted within the balloon catheter and positioned distally in the LAD, and balloon angioplasty was performed with a 2.5 mm compliant balloon followed by placement of two sirolimus-eluting stents (2.5 mm diameter by 28 mm long stent distally and a 2.75 mm diameter by 13 mm long stent proximally). The final angiographic result for the LAD is shown in Figure 11-10 and Videos 11-8, 11-9. Satisfied with the result, the operator chose a 4.0 mm by 15 mm long bare-metal stent for the right coronary artery and postdilated it with a 4.5 mm noncompliant balloon (Figure 11-11). Hemostasis was achieved at the completion of the case by use of a closure device.

Discussion

Chronic total occlusions are fairly common. It is estimated that about one third of patients undergoing angiography for evaluation of coronary disease have at least one chronically occluded artery, with the right coronary artery most commonly involved.1 However, despite their prevalence, only about 10% of percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) involve CTOs. In fact, many interventionalists are reluctant to attempt PCI of a chronic occlusion because of the lower success rate, the potential risk of perforation, and the commitment in time and patience required by the operator. For these reasons, the presence of one or more chronically occluded arteries in the setting of multivessel disease is often the justification for choosing coronary bypass surgery instead of multivessel PCI.2 The case presented here with a chronically occluded LAD and a focal lesion in the RCA is an example of a case where many physicians might have chosen bypass surgery as the initial revascularization strategy instead of a PCI strategy.

Many patients with CTO are asymptomatic and can be treated medically; but, as is present in this case, chronic stable angina is common and most patients manifest ischemia on a stress test.1 In addition to improvement in anginal symptoms and the freedom from need for coronary bypass surgery, successful PCI of a chronically-occluded coronary artery is also associated with improvement in left ventricular function and improved survival.3,4 One nonrandomized observational study involving over 2000 patients undergoing PCI for a chronic total occlusion during the 1980-1999 time period observed a success rate of 70% and an in-hospital adverse event rate that was similar between CTO patients (3.8%) and non-CTO patients (3.7%).4 Ten-year survival was better if the CTO was successfully opened (73.5%), compared to patients with failed CTO treatment (65%).4 It should be emphasized that, despite these apparent benefits, PCI for a chronic total occlusion is not justified in asymptomatic patients without evidence of ischemia and with normal left ventricular function.3

In patients with chronically occluded arteries, the major obstacle to success lies in the inability to pass a guidewire through the occluded segment. Predictors of successful wire passage include: 1) short duration of occlusion; 2) short length of occlusion; 3) tapered entry into the stump; 4) absence of a side branch at the occluded site; and 5) lack of lesion calcification, vessel tortuosity, or ostial location.5 Numerous techniques, devices, and strategies have been designed to improve procedural success.5 Advances in guidewire technology, particularly the tapered tip and stiff-tipped guidewires, have helped many operators achieve success for anterograde attempts at crossing the lesion.3,6 Furthermore, the use of another angiographic catheter to image the collateral vessels originating from another coronary artery, as used in this case, greatly facilitates success and eliminates much of the uncertainty, particularly in the presence of long occlusions. Guide backup is important to allow the operator the ability to push and penetrate the fibrous cap of the occlusion. Loading the guidewire into an over-the-wire balloon allows the operator to advance the balloon close to the occluded site and provides additional backup. In addition, it allows the operator to exchange for a floppy-tipped wire once the occlusion is crossed, preventing the migration of the stiff-tipped wire into a small branch and leading to a distal perforation. If anterograde approaches fail, experts in total occlusion angioplasty have developed numerous retrograde approaches via the collateral vessels to penetrate the distal cap.3

The risk of a chronic total occlusion PCI is fairly low and there is usually little or no consequence if the attempt fails. However, there are unique complications associated with a CTO PCI. These include perforation, proximal dissection and loss of side branches proximal to the occlusion, damage to the collateral vessels, and the associated risk of a prolonged procedure including excessive contrast use and radiation exposure. The risk of perforation for CTO PCI is about 0.9% compared to 0.2% in the non-CTO population.3 To minimize the consequences of a wire perforation complicating an attempt at PCI of CTO, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors or direct thrombin inhibitors without antidotes should not be used until the operator is confident that the wire is safely in the distal true lumen. Unfractionated heparin is a wise choice as it can be readily reversed in the event of a wire perforation.

Interestingly, collaterals appear to regress almost immediately after a successful PCI of a CTO.7,8 Therefore, stent thrombosis occurring after successful PCI for a CTO might result in an acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, as the collaterals previously present can no longer be relied upon for ischemic protection if the artery occludes.

The final challenge relates to maintaining patency and preventing restenosis. Reocclusion rates are as high as 10% to 15% after stenting9 and restenosis with bare-metal stents approaches 30%.10 Similar to other lesion subtypes, drug-eluting stents reduce restenosis compared to bare-metal stents in patients undergoing chronic total occlusion PCI,11 and thus, in the absence of contraindications, drug-eluting stents are preferable in this complex lesion subgroup.

1 Stone G.W., Kandzari D.E., Mehran R., Colombo A., et al. Percutaneous recanalization of chronically occluded coronary arteries. A consensus document. Part I. Circulation. 2005;112:2364-2372.

2 Christofferson R.D., Lehmann K.G., Martin G.V., Every N., Caldwell J.H., Kapadia S.R. Effect of chronic total occlusion on treatment strategy. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:1088-1091.

3 Grantham J.A., Marso S.P., Spertus J., House J., Holmes D.R., Rutherford B.D. Chronic total occlusion angioplasty in the United States. J Am Coll Cardiol Interv. 2009;2:479-486.

4 Suero J.A., Marso S.P., Jones P.G., Laster S.B., Huber K.C., Giorgi L.V., Johnson W.L., Rutherford B.D. Procedural outcomes and long-term survival among patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention of a chronic total occlusion in native coronary arteries: A 20-year experience. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:409-414.

5 Stone G.W., Reifart N.J., Moussa I., Hoye A., et al. Percutaneous recanalization of chronically occluded coronary arteries. A consensus document. Part II. Circulation. 2005;112:2530-2537.

6 Saito S., Tanaka S., Hiroe Y., Miyashita Y., Takahashi S., Satake S., Tanaka K. Angioplasty for chronic total occlusion by using tapered tip guide wires. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2003;59:305-311.

7 Werner G.S., Richartz B.M., Gastmann O., Ferrari M., Figulla H.R. Immediate changes of collateral function after successful recanalization of chronic total coronary occlusions. Circulation. 2000;102:2959-2965.

8 Zimarino M., Ausiello A., Contegiacomo G., Riccardi I., Renda G., DiIorio C., Caterina R. Rapid decline of collateral circulation increases susceptibility to myocardial ischemia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:59-65.

9 for theBuller C.E., Dzavik V., Carere R.G., Mancini J., Barbeau G., Lazzam C., Anderson T.J., Knudtson M.L., Marquis J.F., Suzuki T., Cohen E.A., Fox R.S., Teo K.K., TOSCA Investigators. Primary stenting versus ballon angioplasty in occluded coronary arteries. The Total Occlusion Study of Canada (TOSCA). Circulation. 1999;100:236-242.

10 Sirnes P.A., Gold S., Myreng Y., Mølstad P., Emanuelsson H., Albertsson P., Brekke M., Mangschau A., Endresen K., Kjekshus J. Stenting in chronic coronary occlusion (SICCO): A randomized, controlled trial of adding stent implantation after successful angioplasty. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;28:1444-1451.

11 Suttorp M.J., Laarman G.J., Rahel B.M., et al. Primary stenting of totally occluded native coronary arteries II (PRISON II): A randomized comparison of bare-metal stent implantation with sirolimus-eluting stent implantation for the treatment of total coronary occlusions. Circulation. 2006;114:921-928.