CHAPTER 11 Brief Psychotherapy: An Overview

Despite the notion that it is a long-term endeavor, most data indicate that psychotherapy as it is practiced in the real world has a short course. Therefore, it is usually “brief therapy” even if its duration is not specified as such at the outset. Well before the nationwide impact of managed care was felt, studies consistently showed that outpatient psychotherapy typically lasted 6 to 10 sessions. Data on national outpatient psychotherapy utilization obtained in 1987—early in the takeover of managed care—showed that 70% of psychotherapy users received 10 or fewer sessions. Only 15% of this large sample had 21 or more visits with their therapist.1

HISTORY OF BRIEF PSYCHOTHERAPY

The modern era started in the 1960s when Sifneos and Malan independently developed the first theoretically coherent, short-term psychotherapies. The increased activity of Ferenczi and Rank, Lindemann’s crisis work, Grinker and Spiegel’s push for brevity, Alexander and French’s flexible framework, and Balint’s finding and holding the focus were all technical innovations, but none constituted a whole new method. Malan and Sifneos each invented ways of working that were not a grab bag of techniques but each a whole new therapy, with a coherent body of theory out of which grew an organized, specified way of proceeding.2,3

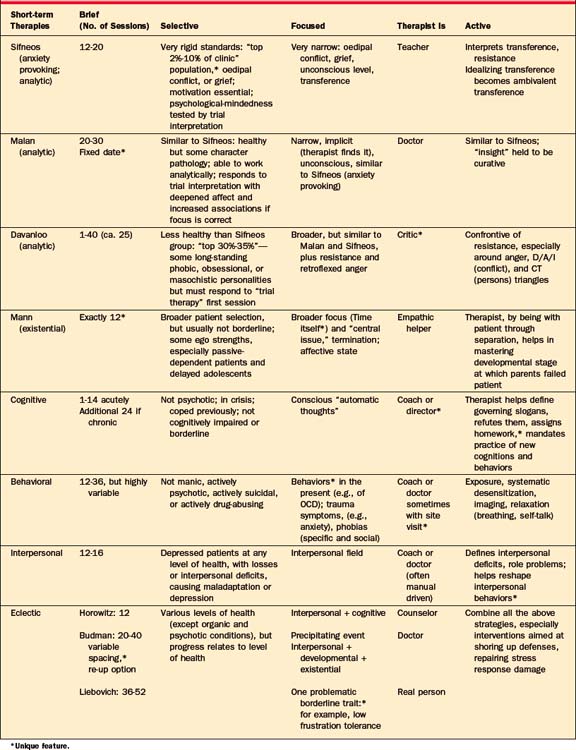

Over time, as therapies became briefer, they became more focused and the therapist became more active. But brevity, focus, and therapist activity are ways in which short-term therapies differ, not only from long-term therapy, but also typically from one another. Patient selection makes up a fourth “essence” in the description of the short-term psychotherapies. Table 11-1 shows brevity, selectivity, focus, and therapist activity as the organizing principles for the therapies summarized in the columns below each “essence.”

MODERN BRIEF PSYCHOTHERAPIES

There are four general schools of brief psychotherapy: (1) psychodynamic; (2) cognitive-behavioral; (3) interpersonal; and (4) eclectic. Each has indications and contraindications,4–6 but it is worth acknowledging at the outset that there is no conclusive evidence that any one short-term psychotherapy is more efficacious than another.7–10

Psychodynamic Short-term Therapies

Malan’s method11,12 is similar, but the therapist discerns and holds the focus without explicitly defining it for the patient. (In the initial trial, if the therapist has in mind the correct focus, there will be a deepening of affect and an increase in associations as the therapist tests it.) A unique feature of this treatment is that Malan sets a date to stop once the goal is in sight and the patient demonstrates capacity to work on his or her own. A fixed date (rather than the customary set number of sessions) avoids the chore of keeping track if acting out causes missed sessions or scheduling errors.

Malan’s work is reminiscent of the British object-relations school. Like Sifneos, he sees interpretation as curative, but he aims less at defenses than at the objects they relate to. In other words, the therapist will call attention to behavior toward the therapist, but rather than asking what affect is being warded off, Malan wants to know more about the original object in the nuclear conflict who set up the transference in the first place. Malan’s later work converges toward that of Davanloo’s,8,13,14 so that his and Malan’s approaches are conceptually similar.

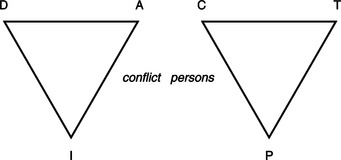

As shown in Figure 11-1, the therapist works with this “triangle of conflict”—which goes from defense (D) to affect (A) to impulse (I), in relation to the “triangle of persons.” This begins with a problematic current object (C), one mentioned in the first half of the initial interview. Then investigation moves to the therapist (T), who the patient has just been protecting from anger, and then to the parent (P) who taught such patterns in the first place. One or two circuits around the “D/A/I” (conflict) triangle in relation to three points of the “C/T/P” (persons) triangle constitute the “trial therapy.” This is a more elaborate version of the trial interpretations Malan and Sifneos use to test motivation and psychological-mindedness. Davanloo’s patients lack the ability to distinguish between points in the “conflict [Defense/Affect/Impulse] triangle” or to experience negative affects directly. By trolling the D/A/I triangle around the “persons [Current object/Therapist/Parent] triangle,” Davanloo forces the frigid patient to feel and creates a mastery experience for the patient.

The dynamic-existential method of James Mann15,16 relied on a strict limit of exactly 12 sessions. Time is not just a reality, a part of the framework, but time is an actual tool of treatment. Twelve sessions, which Mann chose somewhat arbitrarily, is sufficient time to do important work but short enough to put the patient under pressure. This set number with no reprieve is both enough time and too little. It thrusts the patient and the therapist up against the existential reality they both tend to deny: Time is running out.

No other short-term therapy seems to require so much of the therapist. And even if this method does not appeal to all short-term therapists, almost every subsequent theorist in the field seems to have been influenced by Mann to some degree—even Budman and Gurman,17 whose use of time appears so unlike Mann’s. It is described somewhat in detail here because the interaction of therapist activity with phases of treatment is so clearly highlighted.

Underlying the focus the patient brings, Mann posits a “central issue” (analogous to a core conflict) in relation to the all-important issue, “time itself.” The therapist is a timekeeper who existentially stays with the patient through separations, helping master the developmental stages in which parents failed the patient. Mann’s theoretical point of departure (which probably followed the empirical finding that 12 sessions was about right) is Winnicott’s18 notion that time sense is intimately connected to reality testing, a “capacity for concern,” and unimpaired object relationships. A better sense of time and its limits is the soil for growing a better sense of objects.

Cognitive-Behavioral Brief Therapies

The behavioral therapies have a decades-long history and a good record of achievement. The cognitive therapies are the inheritors of this earlier track record. What the two have in common is that neither addresses “root causes” of disorders of mental life, but focus almost exclusively on the patient’s outward manifestations. These “nonpsychological” or “non–insight-oriented” styles of therapy are broadly applicable, both in terms of patients and problems. (For the cognitive-behavioral therapies, see Chapter 16.)

The method of Aaron Beck19–21 aims at bringing the patient’s “automatic” (preconscious) thoughts into awareness and demonstrating how these thoughts affect behavior and feelings. The basic thrust is to challenge them consciously, and to practice new behaviors that change the picture of the world and the self in it. Beck says that an individual’s interpretation of events in the world is encapsulated in these fleeting thoughts, which are often cognitions at the fringes of consciousness. These “automatic thoughts” mediate between an event and the affective and behavioral response. The patient labors under a set of slogans that, by their labeling function, ossify the worldview and inhibit experimenting with new behaviors.

Interpersonal Therapy

Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT), developed by Klerman and colleagues,22 is a highly formalized (“manualized”) treatment. It was developed primarily to treat patients with depression related to grief or loss, interpersonal disputes, or interpersonal skill deficits, but its applicability is sometimes broader than just those conditions.

Temperamental fit between the patient and therapist plays a large role. Crits-Christoph7 notes that “patients who have more interest in examining the subtle, complex meanings of events and interpersonal transactions are a better match” for expressive treatment, whereas those with a more concrete style may prefer cognitive therapy or IPT (p. 157). This psychotherapy deemphasizes the transference and focuses not on mental content, but on the process of the patient’s interaction with others. In IPT, behavior and communications are taken at face value. Consequently, therapists who need to find creativity in their work may dislike IPT. The strength of the method is that it poses little risk of iatrogenic harm, even to the fragile patient, and even in the hands of the inexperienced therapist.

Strupp and colleagues23 also lay claim to the interpersonal model. This too is a method important in research because its reproducibility has been studied and its influences continue to evolve.24 In it, the focus the patient brings helps the therapist to generate, recognize, and organize therapeutic data. The focus is commonly stated in terms of a cardinal symptom, a specific intrapsychic conflict or impasse, a maladaptive picture of the self, or a persistent interpersonal dilemma. It is supposed to exemplify a central pattern of interpersonal role behavior in which the patient unconsciously casts himself or herself. The method for such investigations is narrative, “the telling of a story to oneself and others. Hence, the focus is organized in the form of a schematic story outline” to provide a structure for “narrating the central interpersonal stories” of a patient’s life (Strupp and Binder,23 p. 68).

The Core Conflictual Relationship Theme (CCRT) method is another formalized therapy that examines narratives. Based on Luborsky’s25–27 CCRT, it assumes that each patient has a predominant and specific transference pattern, that the pattern is based on early experience, that it is activated in important relationships, that it distorts those relationships, that it is constantly repeated in the patient’s life, and that it appears in the therapeutic relationship. A major difference in the CCRT method from examinations of the transference in the many dynamic brief therapies, however, is the systematic, active method of ferreting out the CCRT.

Eclectic Therapies

The “eclectic” brief therapies2,28 are characterized by combinations and integrations of multiple theories and techniques.

Horowitz and colleagues29–31 owe a debt to a broad literature on stress, coping, and adaptation that spans the cognitive, behavioral, phenomenological, and ego psychological realms. The point of departure is the normal stress response: the individual perceives the event, a loss or death. The mind then reacts with outcry (“No, no!”) and then denial (“It’s not true!”). These two states, denial and outcry, alternate so that the subjective experience is of unwanted intrusion of the image of the lost. Over time, “grief work” proceeds so that “working through” goes to completion.

The pathological side of this normal response to stress occurs in the stage of perception of the event when the individual is overwhelmed. In the outcry stage there is panic, confusion, or exhaustion. In the denial stage there is maladaptive avoidance or withdrawal by suicide, drug and alcohol abuse, dissociation, or counterphobic frenzy. In the more complex stage of intrusion, the individual experiences alternation of flooded states of sadness and fear, rage and guilt, which alternate with numbness. If working through is blocked, there ensue hibernative or frozen states, constriction, or psychosomatic responses. If completion is not reached, there is ultimately an inability to work or to love.

The eclectic brief therapy of Budman and Gurman17 rests on the interpersonal, developmental, and existential (IDE) focus. A major feature here is the belief that maximal benefit from therapy occurs early, and the optimal time for change is early in treatment. They begin with a systematic approach that begins with the individual’s reason for seeking therapy at this time. The patient’s age, date of birth, and any appropriate developmental stage–related events or anniversaries are noted. Major changes in the patient’s social support are reviewed. Especially important in the Budman-Gurman system is substance abuse and its contribution to the presentation at this time.

Budman and Gurman17 are not snobbish about the capacity of any one course of treatment to cure the patient completely, and they welcome the patient back again in successive developmental stages at developmental crises. A particular value of this treatment is that it is nonperfectionistic, both in pulling a particular phase of therapy to an end and the lack of a feeling of failure on resuming treatment. The picture one develops of this approach is of clusters of therapies ranging along important nodal points in the individual’s development.

THE ESSENTIAL FEATURES OF BRIEF THERAPY

The Initial Evaluation

Some patients do well in any form of short-term treatment, for example, the high-functioning graduate student who cannot complete a dissertation. But between these extremes fall the majority. If the patient is relatively healthy, there are more options: Sifneos may be beyond the reach of the average patient, but there are Malan, Mann, and Davanloo. If the patient is less healthy, the methods of Budman and Gurman may work well, or of Horowitz, especially if there is a traumatic event to serve as a focus. If the patient is quite challenged, the Sifneos anxiety-suppressive treatment is often useful, or cognitive therapy or IPT, depending on the extent to which the focal problems are cognitive or interpersonal. Even some patients with borderline personality disorder may find help in the methods of Leibovich. The balance of this chapter presents a broadly workable algorithm for eclectic therapy.

Patient Selection

A two-session evaluation format is recommended to determine whether a patient is appropriate. The array of inclusion and exclusion criteria in Table 11-2 is fairly general, covering most forms of brief therapy. Also, they are restrictive—many patients will be screened out. For the novice brief therapist, however, the faithful use of these criteria will provide nearly ideal brief therapy patients.

| Exclusion Criteria Active psychosis Acute or severe substance abuse Acute risk of self-harm |

| Inclusion Criteria Moderate emotional distress A real desire for relief A specific or circumscribed problem History of one positive relationship Function in one area of life Ability to commit to treatment |

Developing a Focus

The focus is probably the most misunderstood aspect of brief therapy.32 Many writers talk about “the focus” in a circular and mysterious manner, as if the whole success of the treatment rests on finding the one correct focus. What is needed, however, is a focus that both the therapist and patient can agree on and that fits the therapist’s approach. For instance, the therapist can start with the “metaphoric function” of a symptom (Friedman & Fanger,33 p. 58). The treatment is then focused around that symptom, its meaning to the patient, and its consequences. Goals are stated in a positive language, assessed as observable behavior—goals that are important to the patient and congruent with the patient’s culture.

Another technique for finding a focus is the “why now?” technique used by Budman and Gurman.17 The triggering event for therapy is often ideal, and the technique is applied by repeatedly asking the patient, “Why did you come for treatment now? Why today rather than last week, tomorrow?” Or failing these, “Think back to the exact moment you decided to get help. What were you doing at that moment? What had just happened? What was about to happen?”

These strategies disclose four common treatment foci:

Completing the Initial Evaluation and Setting Goals

The two-session evaluation format also allows the therapist to see how the patient responds to the therapist and to therapy. It can be enlightening to give the patient some kind of homework to complete between the two sessions. An initial positive response and feeling a little better in the second session bodes well, whereas a strong negative reaction conveys a worse prognosis. A more ambivalent response, such as forgetting the task, may signal problems with motivation, and this needs to be explored.

Being an Active Therapist

Conducting a brief, 12- to 16-session psychotherapy requires that the therapist be active—but in a certain way. Any single maneuver is useful only when utilized with a larger set of theory-based principles, especially those aimed at finding and repairing the patient’s missing developmental piece, and managing resistance34 (Table 11-3). The therapist must keep the treatment focused and the process of treatment moving forward, never forgetting that focusing itself pushes the therapy along. Several techniques structure and direct the therapy. These include beginning each session with a summary of the important points raised during the last session, restating the focus, and assignment and review of homework. Interventions that focus on the working alliance are important, as are timely interventions that limit silences and discourage deviations from the focus.

| Structured sessions Use of homework Development of the working alliance Limitation on silences Clarification of vague responses Addressing negative transference quickly Limitation of psychological regression |

Transference occurs in all treatments, including brief psychotherapy. Moreover, transference distortions strong enough to wreck a treatment occur in the beginning hours,35 if not the opening minutes of therapy. Despite the fact that many aspects of brief therapy are designed to discourage the development of transference, the therapist must be ready to deal with it when it develops. Two forms are particularly important to recognize quickly: negative and erotized transferences. Transference resistance often has as its first sign some alteration in the frame (such as lateness, absence, or frequent rescheduling) and sometimes a bid by the patient to change the focus. Negative transference can be suspected when the patient responds repeatedly with either angry or devaluing statements, or when he or she experiences the therapy as humiliating. Early erotized transference is signaled by repeated and excessively positive comments, for example, “Oh you know me better than anyone ever has.” Both of these forms of transference should be dealt with quickly from the perspective of reality. The therapist should review the patient’s feelings and reasoning and relate these to the actual interaction. For example, if the therapist was inadvertently offensive, this should be admitted, while undefensively pointing out that the motive was to be helpful.

Phases of Planned Brief Therapy

The termination phase (sessions 8 to 12 or 16) typically is characterized by the therapy settling down, by decreased affect, and by continued work on old material, but not the introduction of new material. When the patient accepts the fact that treatment will end as planned, symptoms typically decrease. In addition to the treatment focus, post-therapy plans and the situational loss of the therapy relationship are explored. Around the termination, it is not unusual for the patient to present some new and often interesting material for discussion. While the therapist may be tempted to explore this new material, to do so is usually a mistake. A better course is clarification of the emergence of new material as a healthy, understandable—but ultimately self-defeating—attempt to extend the treatment. Mild interest in the new material should be shown, but if it is not a true emergency, treatment should end as planned.

1 Olfson M, Pincus HA. Outpatient psychotherapy in the United States, II: patterns of utilization. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:1289-1294.

2 Blais MA. Planned brief therapy. In: Jacobson J, Jacobson A, editors. Psychiatric secrets. Philadelphia: Hanley & Belfus, 1996.

3 Blais MA, Groves JE. Planned brief psychotherapy: an overview. In Stern TA, Herman JB, editors: Psychiatry update and board preparation, ed 2, New York: McGraw-Hill, 2004.

4 Burk J, White H, Havens L. Which short-term therapy? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1979;36:177-186.

5 Marmor J. Short-term dynamic psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry. 1979;136:149-155.

6 Frances A, Clarkin JF. No treatment as the prescription of choice. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38:542-545.

7 Crits-Christoph P. The efficacy of brief dynamic psychotherapy: a meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149:151-158.

8 Winston A, Winston B. Handbook of integrated short-term therapy. New York: American Psychiatric Press, 2002.

9 Leichsenring F, Rabung S, Leibling E. The efficacy of short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy in specific psychiatric disorders: a meta-analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:1208-1216.

10 Svartberg M, Stiles TC, Seltzer MH. Randomized, controlled trial of the effectiveness of short-term dynamic psychotherapy and cognitive therapy for cluster C personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:810-817.

11 Malan DM. The frontier of brief psychotherapy. New York: Plenum, 1976.

12 Malan DM, Osimo F. Psychodynamics, training and outcome in brief psychotherapy. London: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1992.

13 Davanloo H. Short-term dynamic psychotherapy. New York: Jason Aronson, 1989.

14 Della Selva P. Intensive short-term dynamic psychotherapy: theory and technique. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1996.

15 Mann J. Time-limited psychotherapy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1973.

16 Mann J. Time-limited psychotherapy. In: Crits-Christoph P, Barber JP, editors. Handbook of short-term dynamic psychotherapy. New York: Basic Books, 1991.

17 Budman SH, Gurman AS. Theory and practice of brief therapy. New York: Guilford Press, 1988.

18 Winnicott DW. Therapeutic consultations in child psychiatry. New York: Basic Books, 1971.

19 Beck AT, Greenberg RL. Brief cognitive therapies. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1979;2:23-37.

20 Groves J. Essential papers on short-term dynamic therapy. New York: New York University Press, 1996.

21 Dewan MJ, Steenbarger BN, Greenberg RP. The art and science of brief psychotherapies: a practitioner’s guide. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2004.

22 Klerman GL, Weissman MM, Rounsaville BJ, Chevron ES. Interpersonal therapy of depression. New York: Basic Books, 1984.

23 Strupp HH, Binder JL. Psychotherapy in a new key. New York: Basic Books, 1984.

24 Levenson H, Butler SF, Powers TA, Breitman BD. Concise guide to brief dynamic and interpersonal therapy, ed 2. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2002.

25 Luborsky L. Principles of psychoanalytic psychotherapy: a manual for Supportive-Expressive Treatment. New York: Basic Books, 1984.

26 Luborsky L, Mellon J, van Ravenswaay P, et al. A verification of Freud’s grandest clinical hypothesis: the transference. Clin Psychology Rev. 1985;5:231-246.

27 Book H. How to practice brief psychodynamic psychotherapy: the core conflictual relationship theme method. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 1998.

28 Leibovich MA. Why short-term psychotherapy for borderlines? Psychother Psychosom. 1983;39:1-9.

29 Horowitz M, Marmor C, Krupnick J, et al. Personality styles and brief psychotherapy. New York: Basic Books, 1984.

30 Stadter M, Horowitz MJ. Object relations brief therapy: the therapeutic relationship in short-term work. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson, 1996.

31 Groves JE. Difficult patients. In Stern TA, Fricchione GL, Cassem NH, et al, editors: The MGH handbook of general hospital psychiatry, ed 5, Philadelphia: Mosby, 2004.

32 Hall M, Arnold W, Crosby R. Back to basics: the importance of focus selection. Psychotherapy. 1990;27:578-584.

33 Friedman S, Fanger MT. Expanding therapeutic possibilities: getting results in brief psychotherapy. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, 1991.

34 Gustafson JP. The complex secret of brief psychotherapy. New York: WW Norton, 1986.

35 Gill MM, Muslin HL. Early interpretation of transference. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. 1976;24:779-794.

Alexander F. The principle of flexibility. In: Barton HH, editor. Brief therapies. New York: Behavioral Publications, 1971.

Grinker RR, Spiegel JP. Brief psychotherapy in war neuroses. Psychosom Med. 1944;6:123-131.

Lindemann E. Symptomatology and management of acute grief. Am J Psychiatry. 1944;101:141-148.

Sifneos P. Short-term anxiety provoking psychotherapy: a treatment manual. New York: Basic Books, 1992.

Sifneos P. Short-term psychotherapy and emotional crisis. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1972.

Winston A, Laikin M, Pollack J, et al. Short term psychotherapy of personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:190-194.