CHAPTER 11

Adhesive Capsulitis

Brian J. Krabak, MD, MBA, FACSM

Definition

Primary adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder is an idiopathic, progressive, painful but self-limited restriction of active and passive range of motion [1–3]. The onset is insidious and progresses through several stages, usually during the course of 1 to 2 years. These stages include the painful phase, the freezing or adhesive phase, and the thawing or resolution phase. Adhesive capsulitis occurs in approximately 2% to 5% of the general population and accounts for approximately 6% of office visits to shoulder specialists (orthopedists and physiatrists) on a yearly basis [2]. The condition preferentially affects women after the age of 50 years, involves the nondominant shoulder, and develops in the opposite shoulder in 20% to 30% of cases. The primary etiology is unknown, but it is associated with numerous secondary causes, including immobilization, diabetes, hypothyroidism, autoimmune disease, and treatment of breast cancer (Table 11.1).

Table 11.1

Diseases and Conditions Associated with Secondary Adhesive Capsulitis

| Immobilization | Pulmonary tuberculosis | Scleroderma |

| Diabetes mellitus | Chronic lung disease | Post mastectomy |

| Thyroid disease | Myocardial infarction | Cervical radiculitis |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | Cerebrovascular accidents | Peripheral nerve injury |

| Trauma | Rotator cuff disease | Lung cancer |

| Breast cancer |

Modified from Siegel LB, Cohen NJ, Gall EP. Adhesive capsulitis: a sticky issue. Am Fam Physician 1999;59:1843-1852.

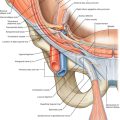

The pathologic process related to adhesive capsulitis involves structures both intrinsic to the glenohumeral joint and surrounding it (Fig. 11.1). Although it is not clear, one theory is that stimulation of synovitis leads to fibrosis due to the activation of various cytokines, including growth factors such as transforming growth factor-β [4]. The pathologic findings of adhesive capsulitis ultimately depend on its stage when it is assessed [1,2]. The painful phase is characterized by synovitis that progresses to capsular thickening (particularly in the anterior and inferior portions of the capsule) with an associated reduction in synovial fluid. As the adhesive phase continues, fibrosis of the capsule is more pronounced, and thickening of the rotator cuff tendons is common. As this phase continues, the glenohumeral joint space becomes contracted and often obliterated. Pathologic change is more consistent with chronic inflammation with resolution of joint space loss during the final stage.

Symptoms

Symptoms will depend on the stage of adhesive capsulitis. In stage 1, the patients experience the gradual onset of progressive pain that is worse during the night and exacerbated by overhead activities. They will gradually report a loss of motion with symptoms lasting less than 3 months. In stage 2, there is a progressive increase in pain that is associated with a reduction in the range of motion and decreased use of the affected shoulder [1,2]. The stage can last 9 to 15 months. Stage 3, the “thawing stage,” is characterized by a gradual decrease in pain and increase in the pain-free range of motion. Some individuals will return to normal, but not all (Table 11.2).

Physical Examination

The findings noted on physical examination reflect the stage of adhesive capsulitis development. During the painful and adhesive stages of adhesive capsulitis, there is a measurable reduction in both passive and active shoulder range of motion. Motion is painful, particularly at the extremes of external rotation and abduction [1,2,5]. This pattern of motion loss is consistent with a capsular pattern of passive range of motion loss, which demonstrates a greater limitation in external rotation and abduction followed by an increasing loss of flexion. These signs are similar to those found in osteoarthritis of the glenohumeral joint, in which there is a similar loss of motion with shoulder pain. However, this presentation is in contrast to findings seen in rotator cuff tears, in which active range of motion is restricted but passive range of motion may approximate normal values. A reduced glenohumeral glide is often noted with adhesive capsulitis, especially with inferior translation. The relationship of glenohumeral joint movements independent of scapulothoracic motion should also be noted. Last, the shoulder is often painful to palpation around the rotator cuff tendons distally. As symptoms start to improve and the patient enters the resolution stage, there is a reversal of the loss of motion, with internal rotation being the last to improve.

Neurologic evaluation findings are usually normal in adhesive capsulitis, although manual muscle testing may detect weakness secondary to pain or disuse. However, concomitant rotator cuff involvement is common and could explain true weakness if it is noted on physical examination. The combination of myotomal weakness, altered dermatomal sensation, reflex asymmetry, and positive findings with cervical spine provocative testing is more suggestive of a neurologic cause of shoulder pain [5].

Functional Limitations

Patients often experience sleep disruption as a result of pain or inability to sleep on the affected side. Inability to perform activities of daily living (e.g., fastening a bra in the back, putting on a belt, reaching for a wallet in the back pocket, reaching for a seat belt, combing the hair) is common. Work activities may be limited, particularly those that involve overhead activities (e.g., filing above waist level, stocking shelves, lifting boards or other items). Recreational activities (e.g., difficulty serving or throwing a ball, inability to do the crawl stroke in swimming) are also affected.

Diagnostic Studies

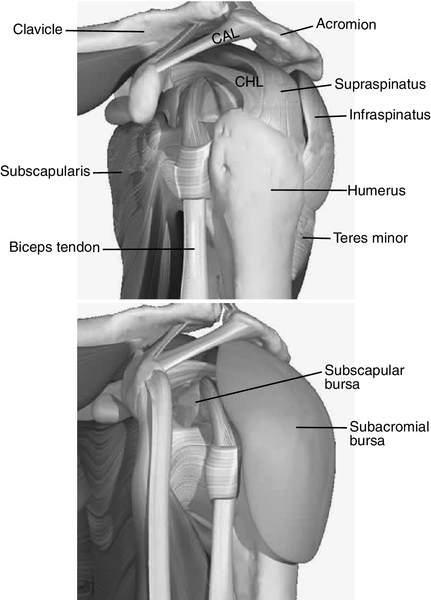

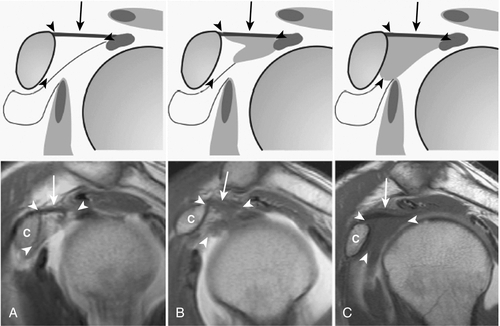

Because adhesive capsulitis is associated with other comorbidities and a population of patients in whom neoplastic processes are common, routine blood work and radiographs should be obtained to rule out secondary causes [6–9]. Radiographs in patients with adhesive capsulitis are generally normal. In advanced stages, joint space narrowing may be noted on arthrograms as there is a reduced volume of injectable contrast material into the joint (Fig. 11.2). Magnetic resonance imaging may also prove to be a useful diagnostic tool; studies have confirmed findings seen at arthroscopy, including thickening of the coracohumeral ligament and obliteration of the subcoracoid space (Fig. 11.3) [6–8]. Ultrasonography allows a dynamic view of the shoulder region with a sensitivity of 91%, a specificity of 100%, and an accuracy of 92% for detection of adhesive capsulitis [9].

Treatment

Initial

The treatment goals depend on the stage of adhesive capsulitis, but the general goals are to decrease pain and inflammation while increasing the shoulder range of motion in all planes [1–3]. Initially, pain and inflammation should be managed with ice, medications, and activity modifications. Reducing inflammation and pain through the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs is generally advocated, although it has not been clearly shown to have an impact on the resolution of pain [2]. A short trial of oral steroids has been shown to more rapidly decrease pain compared with placebo, but the benefits are not sustained during long-term follow-up [2,10]. Similarly, intra-articular injection of corticosteroids (with or without lidocaine) has been shown to be helpful during the early stages of adhesive capsulitis compared with placebo, but it does not change long-term outcomes [2].

Rehabilitation

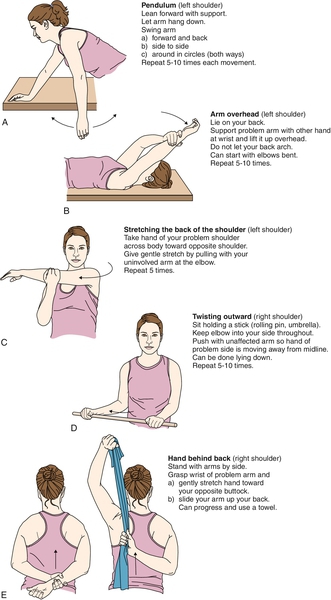

Despite the lack of significant well-conducted clinical trials, the standard of treatment mainly involves physical therapy and home exercises to restore range of motion for the treatment of adhesive capsulitis [1,2,10–12]. The clinician will gauge the need for physical therapy versus a home exercise program and rate of progression of therapy as adhesive capsulitis can take months to years to resolve. Factors affecting the setting and pace of rehabilitation include the severity of the patient’s symptoms, physical examination findings, ability to perform the exercises appropriately, and compliance with a home exercise program. Initially, pendulum exercises, overhead stretches, and crossed adduction of the affected arm should be taught to patients while they are in the physician’s office once adhesive capsulitis is suspected to prevent further loss of function (Fig. 11.4). Some physicians will manage the patient through a home exercise program with periodic follow-up visits to review the patient’s progress. Others will implement physical therapy early to manage pain, to improve the pain-free range of motion, and to prevent further contraction of the joint capsule. As the patient progresses with physical therapy, a more detailed home exercise program should be implemented on the basis of the patient’s understanding of and compliance with the exercises. If the patient shows continued progress with less pain and improved range of motion, exercises should be graduated to strengthening of rotator cuff muscles and periscapular stabilizers. The physician should be cognizant of the cost of prolonged physical therapy and encourage the patient to maintain compliance with a home exercise program. Once symptoms resolve, patients should be encouraged to continue the home exercise program to maintain range of motion and to prevent recurrence of adhesive capsulitis.

Procedures

In the treatment of adhesive capsulitis, procedures are often performed in conjunction with physical therapy sessions and primarily involve pain-alleviating modalities. These procedures may include intra-articular joint injection, suprascapular nerve blocks, and joint capsule hydrodilation [2,13–15]. As noted before, intra-articular injections can be used to break pain cycles. Several small studies using suprascapular nerve blocks have also reported them to be helpful in breaking pain cycles associated with adhesive capsulitis [13]. Hydrodilation involves glenohumeral injections with saline or lidocaine to lyse adhesions and to distend the capsule. Unfortunately, more studies are needed to fully understand its efficacy [1,14,15].

Surgery

The decision to perform surgery is based on failure of conservative management or an unacceptable quality of life. Manipulation under anesthesia followed by immediate physical therapy focusing on improvement of range of motion of the glenohumeral joint can be helpful for refractory cases. Studies suggest that it results in short-term and long-term improvement in pain and mobility [1,15,16]. However, larger studies are needed to better understand the full impact on recovery. Finally, arthroscopic lysis of adhesions may be an effective option if all else has failed [17,18].

Potential Disease Complications

Most of the complications associated with adhesive capsulitis are related to pain and range of motion loss. Pain is usually transient but can persist for months as the condition runs its clinical course. The loss of range of motion that is seen in adhesive capsulitis is usually regained, but it has been reported that as many as 15% of patients develop permanent loss of full range of motion. This range of motion loss is often not associated with functional deficits [1–3].

Potential Treatment Complications

Treatment complications from conservative management are rare but can include side effects associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and analgesic medications; these include gastrointestinal bleeds, gastritis, toxic hepatitis, and renal failure [19]. Caution should be used in the treatment of patients with congestive heart failure and hypertension because of fluid retention associated with the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Patients undergoing physical therapy could experience significant pain from too aggressive therapeutic exercises or manipulation. In patients undergoing suprascapular nerve blocks, care must be taken to prevent intraneural and intravascular injections. There has been one reported case of a patient suffering a pneumothorax during a suprascapular nerve block when a spinal needle was used [20]. A common surgical complication that can occur is a humeral fracture during manipulations under anesthesia.