CASE 11

Mary is 20 months of age and has been hospitalized with a fever, irritability, and moderate dehydration. Blood work suggests a bacterial infection, with elevated neutrophils (>96%; normal: ˜70%), although the chest radiograph and urinalysis are normal. Computed tomography (CT) indicated intracranial evidence for generalized edema with some compression of the ventricles. Despite the risk associated with elevated cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pressure, a lumbar puncture was performed that showed an elevated white cell count. An analysis of the CSF by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay revealed the presence of Neisseria meningitidis. Mary has been receiving intravenous antibiotics for 30 hours, and there is some improvement in her condition. Query into the child’s background indicated that Mary had been breast fed until she was 3 months of age and had been relatively healthy until this recent infection. Detailed family history reveals that a distant male cousin and an aunt both died at an early age (<2 years) of meningitis. What further tests might you order? What is the significance of the history and findings?

QUESTIONS FOR GROUP DISCUSSION

RECOMMENDED APPROACH

Implications/Analysis of Laboratory Investigation

The white blood cell count and differential indicated an increase in the number of circulating neutrophils, which is consistent with a bacterial infection (see Case 6). Results of the CT scan and lumbar puncture, combined with the PCR, indicated that Mary has neisserial meningitis. PCR is now used instead of culture in major laboratories because it is more accurate, even if the patient has already been taking antibiotics. Considering the family history and the severity of this infection, an investigation into possible autosomal recessive disorders was pursued.

Additional Laboratory Tests

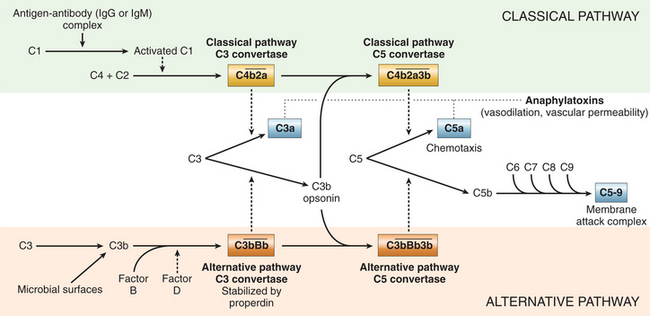

Deficiencies in the complement terminal pathway proteins that compose the membrane attack complex (C5 to C9) or deficiencies in the components of the alternative pathway (e.g., Factor B and properdin) present most commonly as infections with Neisseria meningitidis. Therefore, laboratory investigation should now focus on analysis of the complement pathway (Fig. 11-1).

DIAGNOSIS

Mary was diagnosed with meningococcal meningitis associated with a complement deficiency in one of the components of the terminal pathway. Neisseria meningitidis, a gram-negative bacterium, is surrounded by a polysaccharide capsule whose composition defines the serogroup of the pathogen. Five serogroups (A, B, C, Y, and W-135) cause most of the infections in North America. Patients with deficiencies in the terminal complement pathway are susceptible to infections with all Neisseria species.

REGULATORY PROTEINS

Complement activity and deleterious complement effects on autologous cells are minimized by a variety of soluble, or membrane-bound, proteins. These natural regulatory molecules are important physiologically for homeostasis of the complement cascades. Some of these proteins are associated exclusively with one complement activation pathway or another, whereas others are protective in a more general way. Regulatory proteins that regulate both pathways include (a) decay-accelerating factor that inhibits formation of both C3 convertases; (b) S-protein, CD59, and homologous restriction factor, all of which inhibit formation of the membrane attack complex of the terminal pathway; and (c) the C1 inhibitor protein that prevents spontaneous activation of the classical pathway of complement. The role of the complement system in host defense is underscored when one considers the clinical consequences of microbial evasion strategies and genetic complement deficiencies.