CHAPTER 109

Post-Mastectomy Pain Syndrome

Definition

Post-mastectomy pain syndrome (PMPS) is a chronic pain condition, typically neuropathic in nature, that can follow surgery to the breast [1]. PMPS can occur with any surgery to the breast including mastectomy, lumpectomy, reconstruction, and augmentation, although symptoms of post-mastectomy pain are reduced with sentinel lymph node procedures [2,3]. PMPS affects approximately 40% to 52% of patients after breast surgery [3–5]. The risk factors for development of PMPS include younger age, more extensive surgery, more than 15 lymph nodes removed, more immediate postoperative pain, and anxiety [2,4,6]. Within the first 24 hours of surgery, 60% of patients have severe pain [7]. PMPS typically is manifested as phantom breast pain, intercostobrachial neuropathy, or incisional pain. Early management includes pain control, desensitization techniques, and shoulder range of motion. Chronic management includes neuropathic pain agents, interventional procedures, and rehabilitation. Primary objectives of management include sleep preservation, maintenance of shoulder function, and vocational rehabilitation.

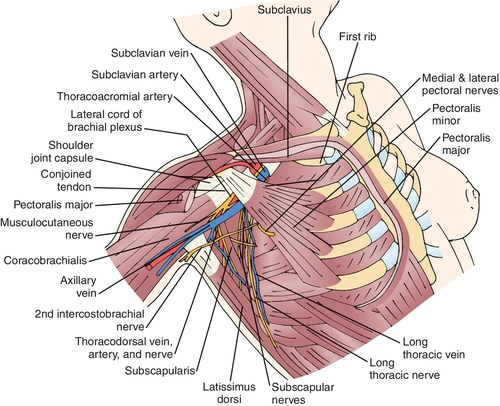

Classification of PMPS can be divided into four categories: phantom breast pain, intercostobrachial neuralgia, myogenic pain, and neuroma pain [8]. Phantom pain is identified in 23% of post-mastectomy patients and consists of painful sensations in the area of the removed breast [9]. The intercostobrachial nerve is the lateral cutaneous nerve of the second thoracic root. It courses along the axillary vein and then provides sensation to the axilla and breast (Fig. 109.1). The intercostobrachial nerve is frequently stretched or sacrificed during axillary lymph node dissections and is a common cause of PMPS [8,10,11]. Myogenic pain is common after mastectomy and is associated with surgical irritation and immobilization. The scar from breast surgery can be a generator of pain. The pain has been attributed to underlying neuroma formation, axon impingement, and scar retraction [8,12].

Symptoms

The symptoms associated with PMPS include shooting, stabbing, burning, and pins and needles sensations in the breast, axilla, or medial arm [1,3,8,13–15]. In addition, patients complain of symptoms of tightness and fullness in the axilla. Pain is aggravated by shoulder movement, stretching, straining, and direct contact with clothes [3,13]. The symptoms of PMPS are usually nonprogressive and have been found to persist in half of patients observed for 9 years [1,13]. PMPS results in functional loss and sleep disruption, and these may be common presenting complaints [1,12].

Physical Examination

The primary aspects of the physical examination include exclusion of other causes of the identified pain and classification of PMPS. General inspection should be performed to evaluate for muscle wasting, asymmetry, and gross masses. The musculoskeletal examination should focus on shoulder range and function; muscle restriction in the pectoralis major and minor; and costovertebral, costochondral, and rib integrity. A careful skin examination should be performed to assess for scar adherence, fibrosis, scar tenderness, neuromas, infection, and recurrence of malignant disease. The lymphatic examination should be performed to assess for lymphadenopathy in lymphatic distributions not already dissected. The neurologic examination includes motor testing of the shoulder girdle, focusing on motor nerves potentially affected by breast surgery (thoracodorsal, long thoracic, medial and lateral pectoral). Sensory testing should include all breast dermatomes T1-T5. Particular attention should be paid to the posterior thorax dermatome as this can be a clue to spinal disease. The sensory examination of the axilla should identify the distribution, severity, and type of sensory abnormality. The complete neurologic examination should include a full assessment of ipsilateral upper extremity motor, reflex, and sensory function.

Functional Limitations

The major functional limitations with PMPS include loss of shoulder range of motion, lifting restrictions, and sleep disruption. Loss of shoulder range of motion is attributed to maintenance of the more comfortable adducted position, resulting in restricted abduction and external rotation [13]. Concurrently, restriction in the pectoralis minor and major results in decreased forward flexion and extension. Limitations with lifting result in diminished capacity to perform household duties (vacuuming, laundry), occupational duties (stocking shelves), and vocational pursuits [1,12,13]. Sleep disruption affects 50% of patients with PMPS and can lead to global daytime dysfunction [13].

Diagnostic Studies

Diagnostic studies are used primarily to exclude other causes of pain. Recurrent malignant neoplasms can be excluded by mammography, magnetic resonance imaging, or positron emission tomography scans. Dedicated imaging of the thoracic spine is warranted to exclude other suspected causes of neuropathic pain in the breast dermatomes, such as radiculopathy. Electrodiagnosis can be useful to exclude motor nerve abnormalities and plexopathy.

Treatment

Initial

The initial management of PMPS commences perioperatively. This includes minimizing dissection, nerve-sparing procedures, and early pain control. Early pain control is imperative because severe early postoperative pain is one of the most consistent factors in PMPS [5,7]. Early postoperative pain control is typically accomplished with judicious use of opiates and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. A study found pregabalin in a single 75-mg dose preoperatively and 12 hours postoperatively to reduce pain [16]. Early desensitization techniques can help limit neuropathic symptoms and can be initiated once the incision is healed. For those with uncontrolled pain that limits sleep and daily function, neuropathic pain medications can be initiated. Some pharmaceuticals, such as capsaicin, amitriptyline, nortriptyline, gabapentin, pregabalin, and lidocaine patches, have been studied and found to be effective [8,14,16,17]. Long-acting opiates can be used when these agents fail to control symptoms [14].

Rehabilitation

From a rehabilitation perspective, PMPS management begins immediately postoperatively. The primary factor for rehabilitation management is to identify functional limits. Clearly, shoulder restriction is a major factor in the functional limitations from PMPS. Shoulder rehabilitation begins with stretching of the pectoralis complex and latissimus dorsi followed by glenohumeral range of motion and finally scapulohumeral retraining. Upper extremity strengthening commences once full shoulder range of motion is obtained. Targeted muscle groups for weight training include the latissimus dorsi, trapezius, scapular stabilizers, rotator cuff, and deltoid. Weight training should be performed with low weights and high repetitions. The final phase of rehabilitation is task-specific training, progressing from basic activities of daily living to household tasks, work-related duties, and recreational pursuits. It is important to guide the breast cancer survivor through resumption of full activity to avoid unnecessary injury.

Procedures

Procedural management of PMPS is typically limited to regional nerve blocks for pain control [14]. For those with progressive shoulder dysfunction and painful range of motion, local injections in the subacromial space may be beneficial. In addition, myofascial injections with anesthetic preparations or botulinum toxin can be beneficial for myogenic pain.

Surgery

Surgical management of PMPS typically relates to chest wall pain or shoulder dysfunction. Chest wall pain with scar retraction can be managed with scar removal. In addition, soft tissue adherence to chest wall structures may require surgical repair. Adhesive capsulitis as a result of progressive loss of shoulder range of motion may require manipulation under anesthesia for full shoulder range of motion to be obtained.

Potential Disease Complications

The primary potential disease complications from PMPS include adhesive capsulitis, loss of shoulder function, and diminished carrying capacity of the affected extremity. Resultant to this lack of function, patients can lose employment and vocational and recreational capacity. An insidious and life-altering complication of PMPS is sleep disruption. Sleep disruption can result in global dysfunction and health-related complications.

Potential Treatment Complications

Treatment complications are primarily related to side effects from medications. Capsaicin is known to cause painful skin reactions by its mechanism of action. Tricyclic antidepressants have anticholinergic side effects and must be used with caution in patients with cardiac arrhythmias. The main side effects of gabapentin include sedation, tremors, and dizziness. Topical lidocaine patches can result in skin excoriation. Bleeding, infection, and nerve irritation can complicate interventional procedures. Surgical procedures including manipulation under anesthesia and scar removal can result in increased pain and secondary soft tissue restriction.