CHAPTER 106

Pelvic Pain

Definition

Chronic pelvic pain (CPP), a common condition among women, affects up to one in four women of reproductive age at some point in their lifetime [1,2]. It can be an elusive disorder to diagnose and to treat, challenging even the most experienced clinicians. Despite variable opinions as to what constitutes this disorder, a widely accepted definition of CPP is noncyclic pain localized primarily in the anatomic pelvis, the anterior abdominal wall at or below the umbilicus, the lumbosacral spine, or the buttocks [3]. Traditionally, CPP must be of 6 months’ duration and severe enough to cause functional disability or to require treatment. It can be of gynecologic, urologic, gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, or neurologic etiology. The pain that arises from CPP can be categorized into somatic, visceral, neuropathic, or referred pain.

The prevalence of CPP is estimated to be 3.8% in women aged 15 to 73 years, similar to that of asthma, back pain, and migraine headaches. In primary care practices, it is estimated that 39% of women have complained of pelvic pain [1,2,4]. There are no known demographic factors—age, race, ethnicity, education, or socioeconomic status—that put women at risk for development of CPP, although women with CPP tend to be of reproductive age.

Discovering the etiology of CPP (and therefore appropriate treatment) can be difficult because of the broad differential diagnoses and their many overlapping symptoms (see Table 106.1 for a complete list by organ system). In addition, these diagnoses are not mutually exclusive but in many cases may coexist. For example, endometriosis and myofascial pain are often known to overlap. Because of the diagnostic complexity of CPP, an accurate diagnostic approach cannot always be assumed. This is especially true if medical or surgical therapies for discrete diagnoses have failed to provide relief.

Table 106.1

Conditions Associated with Pelvic Pain in Women

Gynecologic

Endometriosis*

Chronic pelvic inflammatory disease*

Pelvic adhesions

Pelvic congestion (pelvic varicosities)

Adenomyosis

Ovarian remnant syndrome

Residual ovary syndrome

Leiomyoma

Endosalpingiosis

Neoplasia

Fallopian tube prolapse (after hysterectomy)

Tuberculous salpingitis

Benign cystic mesothelioma

Postoperative peritoneal cysts

Mental Health Issues

Somatization

Substance abuse

Physical and sexual abuse

Depression

Sleep disorders

Urinary Tract

Interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome*

Recurrent urinary tract infection

Urethral diverticulum

Chronic urethral syndrome

Neoplasia

Radiation cystitis

Gastrointestinal Tract

Irritable bowel syndrome*

Inflammatory bowel disease and other causes of colitis

Diverticular colitis

Chronic intermittent bowel obstruction

Neoplasia

Chronic constipation

Celiac disease (sprue)

Chronic appendicitis

Musculoskeletal

Pelvic floor myalgia*

Myofascial pain (trigger points)*

Coccygodynia

Piriformis syndrome

Hernia

Abnormal posture

Fibromyalgia

Peripartum pelvic pain syndrome

Neurologic Disorders

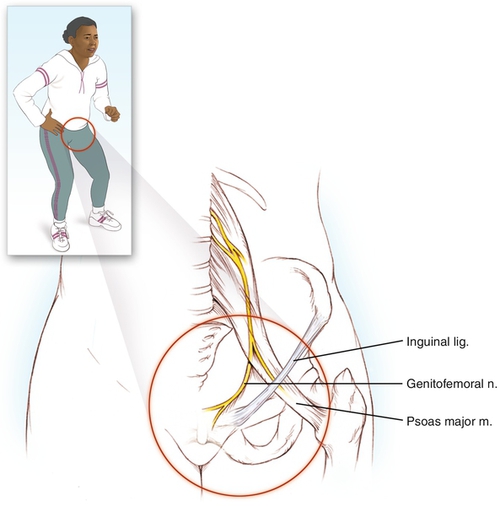

Neuralgia, especially of the iliohypogastric, ilioinguinal, genitofemoral, or pudendal nerves*

Herniated nucleus pulposus

Neoplasia

Neuropathic pain

Abdominal epilepsy

Abdominal migraine

* These diagnoses are the most common causes of chronic pelvic pain and are backed by substantial evidence.

The initial diagnostic approach should begin with a thorough history to narrow the differential diagnosis. The pain history should include pain characteristics such as first occurrence, location, duration, temporal pattern, precipitating and alleviating factors, relationship to urination and defecation, patterns of radiation, intensity, and effect of pain on life activities (such as activities of daily living, sleep, work, sexual intercourse, and social or recreational activities). A monthly pain calendar, which records episodes, location, severity, and associated factors, is useful to obtain accurate and detailed information. The history should also include prior treatments; history of substance abuse; history of sexual, physical, and psychological abuse; and thorough review of systems. A pain map of the body is a useful tool to help the physician and patient specify pain patterns. The usual components of a patient history, such as medical problems, previous surgeries, and reproductive history, should be included as well. To streamline the process of obtaining a history for patients with CPP, the International Pelvic Pain Society has created the Pelvic Pain Assessment Form, which is an excellent and freely reproducible tool that can be found on its website [5].

The most common causes of CPP are of gynecologic, gastrointestinal, urologic, and musculoskeletal origin and include specific diagnoses, such as endometriosis, chronic pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), irritable bowel syndrome, bladder pain syndrome, and myofascial pelvic pain [6].

Gynecologic

Endometriosis

Endometriosis is a common gynecologic condition affecting women of reproductive age. It is characterized by the presence of endometrial tissue (the inner layer of the uterus) outside of the uterus. The extrauterine endometrial implants respond to the hormonal stimuli in the same way as intrauterine endometrium does, causing cyclic bleeding in the sensitive tissues of the peritoneum, ovaries, fallopian tubes, and elsewhere. This process can lead to formation of pelvic adhesions, scar tissue, and endometriomas.

This disorder is found in 10% to 15% of women of reproductive age, in 25% to 40% of women undergoing treatment for infertility, and in 33% of women who have laparoscopy for CPP. Risk factors include early menarche, short menstrual cycles (less than 27 days), and müllerian anomalies that involve vaginal or uterine obstruction of blood flow. Symptoms include long-standing cyclic pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, menorrhagia, and deep dyspareunia. Severity of symptoms does not necessarily correlate with visual disease burden at time of surgery.

Uterine Leiomyomas

Leiomyomas (uterine fibroids, myomas) are benign smooth muscle tumors of the uterus and the most common neoplasm in women of reproductive age, with the highest prevalence in the fifth decade of life. The lifetime incidence of leiomyoma is 50% and up to 60% in women of African descent. Fibroids are thought to grow from estrogen stimulation. The most common symptoms are pressure from an enlarging pelvic mass, pain and dysmenorrhea, and abnormal uterine bleeding. The severity of symptoms is related to the size, number, and location of the tumors, although many women with fibroids are asymptomatic. In general, fibroids shrink after menopause. A myoma that grows rapidly after menopause is concerning for leiomyosarcoma, which occurs in 0.5% of fibroids.

Adenomyosis

Similar to endometriosis, adenomyosis is the presence of ectopic endometrial tissue in the myometrium (muscle layer) of the uterus. Adenomyosis develops from aberrant glands of the basalis layer of the endometrium and causes pain, dysmenorrhea, and menorrhagia. Some women experience intense pelvic cramping and pressure that radiates to the lower back, groin, rectum, and anterior thighs. Symptomatic adenomyosis usually is manifested in women aged 35 to 50 years, although adenomyosis can be found in asymptomatic women. The incidence of this disorder is unknown. As the ectopic endometrial tissue proliferates, the uterus takes on an enlarged, globular shape, which can sometimes be appreciated on examination.

Adhesive Disease

The correlation between abdominal adhesions and CPP is poorly understood, and studies of these are limited. It is thought that certain types of adhesions, particularly densely vascular adhesions to the bowel and peritoneum, cause CPP. Diagnosis can be made only at the time of laparoscopy as there are no examination findings, laboratory tests, or imaging studies that are reliably useful. Risk factors include a history of prior pelvic surgery, PID, endometriosis, inflammatory bowel disease, radiation therapy, and peritoneal dialysis.

Pelvic Congestion Syndrome

Pelvic congestion syndrome is a condition of vascular engorgement of the ovarian veins or internal iliac veins that leads to pelvic pain. Characteristic findings of gross dilation, incompetence, and reflux of the ovarian veins are seen on venography, sometimes forming parovarian pelvic varicosities. Dysfunction in the one-way valves of the ovarian veins is postulated as the underlying etiology. There is limited understanding of the prevalence of this condition as there are no definitive diagnostic criteria. As with most causes of pelvic pain, anatomic anomalies are not necessarily indicative of the presence or severity of pain. Pelvic congestion syndrome has been described only in premenopausal women. Typically, pain is worse after prolonged standing and improves in the morning after rest. Associated symptoms include marked ovarian tenderness, shifting location of pain, and deep dyspareunia or postcoital pain.

Chronic Pelvic Inflammatory Disease

PID starts as an acute condition and can become a chronic condition causing CPP. The transition from acute PID to chronic PID is incompletely understood and occurs in about 18% to 35% of women with acute PID. Women at risk for development of chronic PID include those who are not initially treated for the acute phase or are treated incompletely. In addition, the development of more severe adhesions or tubal damage and persistent pelvic tenderness 30 days after diagnosis and treatment increase the likelihood for development of CPP. Whether a woman is treated with an inpatient or outpatient regimen for acute PID does not have any bearing on the risk for later development of chronic PID or CPP [7]. Most PID is caused by Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Other implicated pathogens are Gardnerella vaginalis, Haemophilus influenzae, enteric gram-negative rods, and Streptococcus agalactiae. Diagnostic criteria and treatment of acute PID are published and maintained by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [8].

Gastrointestinal

Irritable bowel syndrome is a common functional bowel disorder of uncertain etiology characterized by a chronic, relapsing pattern of abdominopelvic pain and altered bowel habits in the absence of an organic cause. Although not all patients with this disorder seek treatment, the estimated prevalence is 10% to 15% in North America. The abdominal and pelvic pain is usually crampy in nature and varies in location, often exacerbated by emotional stress and eating habits and relieved by defecation. Patients also often complain of nongastrointestinal symptoms, such as altered sexual function, dysmenorrhea, urinary frequency, or dyspareunia.

The Rome III criteria are used to diagnose irritable bowel syndrome, and patients must have two of the following: pain relieved with defecation; onset of pain associated with a change in frequency of stool; or onset associated with a change in form (appearance) of stool [9].

Urologic

Chronic bladder pain in the absence of other identifiable etiology has been termed bladder pain syndrome (BPS). Previously called interstitial cystitis (IC), this is actually a misnomer as there is no evidence of underlying evidence of inflammation. For historical reasons, the nomenclature has changed to IC/BPS. IC/BPS is characterized by suprapubic or urethral pain, pressure, or discomfort that is worse with bladder filling and relieved with voiding. The severity of symptoms ranges greatly and may vary from day to day. Other urinary symptoms, such as frequency, urgency, and nocturia, accompany the pain [10]. IC/BPS often coexists with other chronic pain syndromes, such as fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, or myofascial pelvic pain syndrome [11]. The underlying etiology has not been exactly elucidated but may be related to altered integrity of the glycosaminoglycan layer of the bladder.

Because IC/BPS is a clinical diagnosis, there are no characteristic laboratory or imaging findings. A voiding diary that logs fluid intake, voiding volume, and frequency demonstrates the characteristic frequent, low-volume voiding pattern.

Musculoskeletal

Myofascial pelvic pain is pain attributed to short, tight, and tender pelvic floor muscles scattered with characteristic trigger points, small hypersensitive areas within a tight band of muscle (Fig. 106.1). A trigger point can cause local pain and over time lead to regional and diffuse pelvic pain as well as visceral dysfunction, such as constipation or irritative voiding. The exact prevalence of myofascial pelvic pain syndrome is unknown. Determining if CPP is due to a myofascial etiology or caused by another disorder can be challenging. In fact, overlap between pelvic pain disorders is common. For instance, studies have shown that 70% of women with bladder pain syndrome also have myofascial pain, most often involving the levator ani muscles of the pelvic floor [12]. Myofascial pelvic pain is thought to originate from an abnormal response to muscle fiber trauma, causing peripheral and then central sensitization. Inflammatory mediators are released locally when a muscle is injured. Over time, the muscle nociceptors become conditioned to the stimulus and a lower response threshold to inflammatory mediators and mechanical stimulation ensues, leading to muscle hyperalgesia. Continued input from the injured or painful muscle leads to neuroplastic changes in the dorsal spinal cord, resulting in amplified pain to both noxious and non-noxious stimuli. Furthermore, secondary hyperalgesia develops such that pain is perceived outside of the original area of injury [12].

Physical, mechanical, systemic, and psychological factors have been associated with the development of trigger points. Physical factors include injury to the nerves and muscles at the time of childbirth or surgery. Mechanical factors that contribute to myofascial pelvic pain include abnormal posture, leg length discrepancy, gait disturbances, sacroiliac joint dysfunction, and diastasis recti, all of which can trigger asymmetric use of the levator muscles. Systemic factors such as subclinical hypothyroidism, nutritional inadequacies, chronic allergies, and impaired sleep have also been linked to the development and activation of trigger points.

With myofascial pelvic pain, patients often have difficulty in localizing pain. The pain is characterized as achy, throbbing, or pressure-like in quality. Myofascial pelvic pain can radiate to the hip or back and commonly worsens throughout the day, with bowel or bladder function, or after intercourse. During the examination, attention should be paid to the pelvic floor examination. Patients with myofascial pelvic pain will complain of pain when pressure is placed on myofascial trigger points, which are often found in the pubococcygeus and ileococcygeus muscles of the pelvic floor.

Symptoms

The specific symptoms of CPP vary greatly but are important to elicit because they can give diagnostic clues. Pain caused by endometriosis typically worsens premenstrually and throughout menses. Pain accompanied by symptoms of poor urinary flow, urinary hesitancy, or constipation suggests myofascial pelvic pain, pelvic floor muscle dysfunction, or an anatomic defect such as pelvic organ prolapse. Pain with radiation to the lower extremities may indicate myofascial pelvic pain, sacroiliac joint dysfunction, or spinal disease, such as radiculopathy or cord compression. Improvement of pain while supine and aggravation of pain while upright suggest pelvic congestion syndrome. Lateralizing pain accompanied by hematuria may be indicative of urolithiasis or urinary tract obstruction. Crampy abdominal pain with diarrhea or constipation suggests irritable bowel syndrome or diverticular disease. Entry dyspareunia may be a symptom of lichen sclerosus, atrophic vaginitis, or vulvodynia; deep dyspareunia may be a symptom of endometriosis, myofascial pelvic pain syndrome, or chronic PID. Pain that increases with bladder filling and is associated with urinary frequency, nocturia, and painful voiding suggests IC/BPS.

Physical Examination

After a thorough history and review of systems, the clinician narrows the differential diagnosis. The goal of the physical examination is to reproduce, whenever possible, the patient’s pain. Therefore it is important for the clinician to remember that this process can be a stressful and unpleasant experience for the patient. The physical examination—indeed, the entire evaluation—should be systematic and methodical. In the case of CPP, a multispecialty approach to both diagnosis and treatment is now considered standard of care. Therefore clinicians commonly treating patients with CPP should be familiar with the basic physical examination of the multiple organ systems around the pelvis that may give rise to pain symptoms. These clinicians ideally function within a team of experts from various specialties to ensure a complete diagnostic approach.

After a screening examination of the lumbosacral spine is performed, the examination of the pelvis continues with the patient supine. The patient should be asked to identify the areas of most pain. A four-quadrant abdominal examination is then performed with superficial and deep palpation (ideally with the patient’s abdomen relaxed), leaving the area of most pain until last, and taking note of discomfort, hernia, masses, and surgical scars. If hypersensitivity is found on the superficial examination, this can suggest myofascial trigger points. A simple maneuver, the Carnett test, can be used to differentiate myofascial pain from visceral abdominal pain. For the Carnett test to be performed, the area of pain on the abdomen is palpated with one or two digits, and then the patient voluntarily contracts the abdomen by raising legs and head off the table. If pain at the palpation site increases, this is likely a myofascial trigger point, and if pain decreases, it is likely visceral in origin.

The examination continues in the dorsal lithotomy position. The patient should again show the clinician where the area of most pain is. First, begin with examination of the external pelvis, looking at the groin, external genitalia, and perineum for asymmetry or dermatologic abnormality. The soft end of a cotton swab can be used to assess pain in the vestibule, posterior fourchette, and labia; if pain is present, it can be indicative of vulvodynia or vulvar skin disorders.

A lubricated single-digit examination of the pelvic floor is performed next, before placing a speculum or performing a bimanual examination, which can aggravate the muscles of the pelvic floor. The base of the pelvic floor is palpated and the vagina should feel like a soft cylinder. In patients with hypertonic disorders, a shelf of contracted musculature can usually be felt in addition to myofascial trigger points. Myofascial trigger points are small areas of contracted tissue that are exquisitely tender on palpation and produce either direct or referred pain. The bladder base, cul-de-sacs, cervix, uterus, and adnexa should then be palpated, again noting tenderness, symmetry, and fullness, which can be indicative of endometriosis or pelvic masses.

The final part of the genitourinary examination is the speculum examination. A small speculum is suggested as a larger one can be difficult to pass into the vagina if there is pain and discomfort. The clinician should again note symmetry of the position of the cervix; shortening of the uterosacral ligaments causes lateral displacement of the cervix and is a classic finding of endometriosis. Vaginal and cervical culture specimens are obtained as indicated, particularly if chronic PID is suspected. Vaginal atrophy, seen in postmenopausal women with loss of vaginal rugae and lightening of the normal lush pink hue of the vaginal walls, can cause discomfort and is easily treated with vaginal estrogen.

Functional Limitations

CPP frequently results in significant functional limitations. In general, patients with chronic pain syndromes may have psychological distress because of delayed diagnosis and treatment. Chronic unrelieved pain is known to contribute to anxiety, depression, sleep disturbance, and altered family and social roles that may have an impact on all areas of function. Pelvic floor muscle myofascial pain may increase with prolonged sitting or standing, which may limit the patient’s ability to participate in work, social, and recreational activities. In addition, bowel and bladder function may be affected, and in some cases incontinence may result. Many patients with CPP also complain of dyspareunia interfering with normal sexual function.

Diagnostic Studies

In the evaluation of CPP, history and physical examination are the mainstays of diagnosis, although several studies may help narrow the differential or confirm or exclude a specific diagnosis. In general, the most useful imaging modality for pelvic organs is ultrasonography, which can detect uterine fibroids, intrauterine disease, adnexal disease (e.g., endometrioma, ovarian neoplasm), and adenomyosis. Magnetic resonance imaging is preferable to assess adenomyosis. If there is a high suspicion for pelvic congestion syndrome, pelvic venography can be performed. Although there are no imaging studies that are useful in the diagnosis of myofascial pelvic pain syndrome, surface electromyography can provide objective evidence of muscle dysfunction.

Laboratory evaluation can include urine analysis and culture, sexually transmitted infection testing, complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, or thyroid assay as indicated by the patient’s risk factors and comorbid conditions. Results of laboratory tests, such as CA-125, can be elevated in the presence of endometriosis, but the sensitivity and specificity are too low to be of clinical value. When urinary symptoms are present, a urine analysis should be performed to rule out underlying infection, and patients with hematuria should be evaluated with cystoscopy.

Laparoscopy can be used as an extension of the diagnostic regimen. In fact, 40% of all laparoscopies are performed for CPP. When laparoscopy is performed for CPP, 33% of women are found to have endometriosis, 24% are found to have adhesive disease, and 35% have no visible disease [13]. Biopsy of any pathologic process found on laparoscopy is important because visual diagnosis of endometriosis is often unreliable. Diagnostic laparoscopy has the benefit of offering simultaneous treatment; if endometriosis or pelvic adhesions are found during the operation, ablation or resection can be performed. Patients who present with gastrointestinal symptoms should be referred to a gastroenterologist and will likely undergo colonoscopy as part of the evaluation.

Treatment

Initial

Establishing a patient-physician relationship based on trust and confidence is important in treating CPP. During the arduous diagnostic process, concern for the patient should be expressed and her symptoms validated. As with any chronic pain condition, it is important to discuss expectations of symptom improvement and management. Treatment of CPP is a process that often requires time and a multimodality approach to treatment involving primary care providers, physicians from an array of specialties, and physical therapy.

While the patient is going through the diagnostic process, it is reasonable to start empirical treatment based on diagnostic probability. When a specific diagnosis is made, targeted therapy should be initiated. A 4- to 6-week trial of maximum-strength nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is an appropriate first-line therapy. If this is ineffective, a second NSAID may be tried because of variable responses of patients to individual drugs.

In addition to NSAIDs, when a gynecologic etiology is likely, hormonal therapy may be started either sequentially or simultaneously. Oral contraceptive pills should be attempted for two or three cycles, prescribed either in the standard manner or continuously. If the combination of NSAIDs and continuous oral contraceptive pills is unsuccessful after 2 to 3 months, second-line agents may be tried; these include progestins and gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists.

Initial treatment of mild irritable bowel syndrome involves patient education, dietary modification, and behavioral changes. If patients have moderate or severe symptoms, pharmacologic agents may be added.

With IC/BPS, a stepwise approach should be taken for treatment; it may begin with simple measures such as heat or cold to the suprapubic area, avoidance of food or activities that exacerbate pain, and fluid management. Bladder analgesics, such as phenazopyridine or methenamine, may be used initially. For longer term management, non-narcotic and narcotic pain medications can be used, guided by principles used to manage other chronic pain conditions. Intravesical instillation of lidocaine with heparin or sodium bicarbonate may be used to manage pain exacerbations.

Some women find relief of CPP symptoms from complementary and alternative medical treatments, such as acupuncture, acupressure, and nutritional supplements. The decision to pursue these modalities should be individualized as there is a paucity of high-quality studies in the medical literature.

Endometriosis

Treatment of women with presumed or proven endometriosis usually begins with NSAIDs for pain management and combined oral contraceptive pills to induce a relative hypoestrogenic state, thereby decreasing the proliferation of extrauterine endometrial tissue. Long-acting progesterones, such as intramuscular medroxyprogesterone, etonogestrel subdermal implant, or levonorgestrel intrauterine device, are also useful in achieving a hypoestrogenic state. If these first-line therapies fail, GnRH agonists or aromatase inhibitors can be used [6]. If medical therapy fails, laparoscopy can be used to reduce disease burden, or the uterus and ovaries can be removed [13].

Uterine Leiomyomas

In women with fibroids, treatment should be guided by severity of symptoms, nearness to menopause, and desire for childbearing potential. A GnRH agonist, such as intramuscular leuprolide, can be used to help shrink the fibroid burden, although its side effect profile is onerous for some women. Uterine artery embolization, myomectomy (either hysteroscopically or abdominally), and hysterectomy are other treatments. Pregnancy should be avoided after uterine artery embolization, and a cesarean section is usually recommended in the case of pregnancy after myomectomy. If a woman is near menopause and has mild or moderate symptoms, it is reasonable to treat with NSAIDs and to reevaluate after menopause.

Myofascial Pelvic Pain Syndrome

Treatment of myofascial pelvic pain is best done with a multidisciplinary approach. Myofascial pelvic pain is often associated with other diagnoses, such as irritable bowel syndrome, endometriosis, depression, constipation, painful bladder syndrome, and chronic urinary tract infections. It is critical to treat a concomitant diagnosis if one is found because that may be the very thing that incites or exacerbates the myofascial pain. Neurogenic pain may be treated with tricyclic antidepressants or γ-aminobutyric acid analogues (such as gabapentin or pregabalin). However, the mainstay for treatment of myofascial pelvic pain is pelvic floor physical therapy, and specific techniques for physical therapists have been well described.

Rehabilitation

A comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach in managing CPP is of the utmost importance, and physical therapy plays an integral role in this. Physical therapists evaluate the structural, biomechanical, postural, functional, musculoskeletal, and neurologic dysfunctions that may cause, perpetuate, or result from pelvic pain. Involving the physical therapist in the early stage of pelvic pain is highly recommended. Rehabilitative interventions include connective tissue manipulation; behavioral retraining and education for posture, activity, and bowel and bladder habits; therapeutic exercise; neuromuscular reeducation; and manual therapy techniques for joints, soft tissue, and fascia [14]. Physical therapy appears to be most successful when all of these elements are considered and positive findings are addressed through a progressive and individualized treatment program.

Procedures

In the case of myofascial pelvic pain syndrome, patients who improve incompletely with physical therapy may benefit from trigger point injections into the pelvic floor muscles. Trigger point injections are most often performed with local anesthetic, such as lidocaine or bupivacaine [15]. Botulinum toxin A injections have also been used to reduce CPP and pelvic floor muscle spasm [16]. Sacral neuromodulation is an additional treatment option for women with myofascial pelvic pain and has been used in the treatment of refractory, nonobstructive urinary retention, urinary frequency or urgency, and urge incontinence. Although it is not approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of IC/BPS or pelvic pain, some studies suggest a benefit for these conditions [17].

Surgery

If medical therapy fails to bring improvement, diagnostic and potentially therapeutic laparoscopy should be pursued. Laparoscopic adhesiolysis can temporarily alleviate symptoms due to pelvic adhesions; however, adhesions often tend to recur rapidly. The role of hysterectomy in idiopathic CPP is controversial as there is a failure rate of pain resolution of 40%. In addition, there is an unclear understanding of which patients benefit from hysterectomy and which do not [18]. In the case of adenomyosis, hysterectomy is considered the definitive treatment for those who fail to respond to medical management. Other surgical procedures for CPP, such as presacral neurectomy and uterosacral nerve ablation, offer limited improvement in symptoms and are usually no longer performed.

Potential Disease Complications

If it is left untreated, CPP has the potential to cause severe debilitation, both from a personal standpoint and from a societal standpoint. Lessening of quality of life, depression, lost wages, and lack of participation in society can have long-reaching consequences.

Potential Treatment Complications

Potential adverse effects of NSAIDs are well publicized and include gastritis, gastrointestinal ulcers, renal impairment, and cardiac morbidity. GnRH agonists carry risk of early osteoporosis. Complications due to invasive procedures include bleeding and infection.