CHAPTER 105

Occipital Neuralgia

Definition

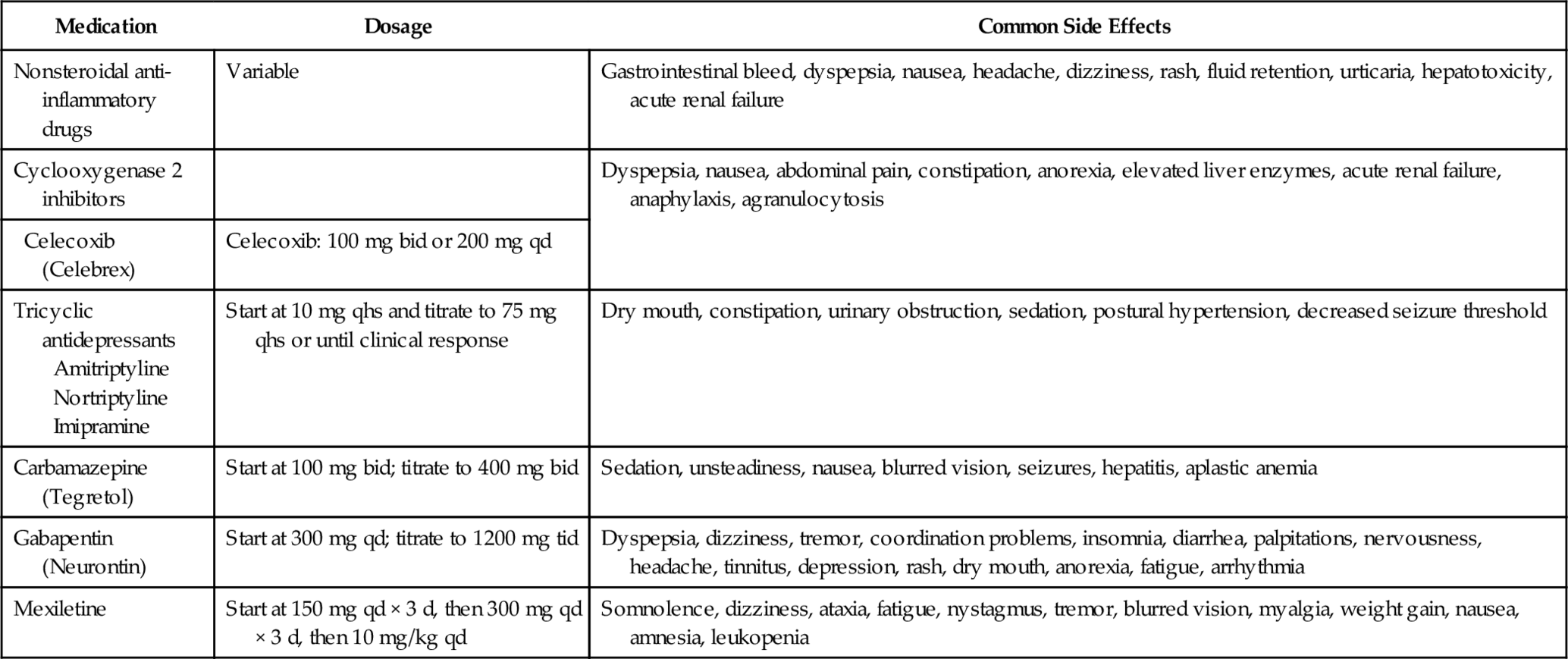

The International Headache Society categorizes occipital neuralgia as a cranial neuralgia and defines it with three diagnostic features: paroxysmal stabbing pain in the distribution of the occipital nerves with tenderness over the affected nerves temporarily relieved by local anesthetic block [1]. Occipital neuralgia can occur in the distribution of the greater and lesser occipital nerves (Fig. 105.1). However, the greater occipital nerve is more commonly involved (90%); in addition, unilateral symptoms are more common (85%) [2]. The condition appears to be more common in women [3].

The pain is described as lancinating, sharp, throbbing, electric shock–like, and often associated with posterior scalp dysesthesia or hyperalgesia [4–6]. Two broad categories of patients with occipital neuralgia are those with structural pathologic changes and those without an apparent cause [7]. Proposed causes include myofascial tightening, trauma of C2 nerve root (whiplash injury), prior skull or suboccipital surgery, other type of nerve entrapment, hypertrophied atlantoepistrophic (C1-C2) ligament, sustained neck muscle contractions, and spondylosis of the cervical facet joints [2,4,6,8–10]. Most patients with occipital neuropathy do not have discernible lesions [11].

Anatomy

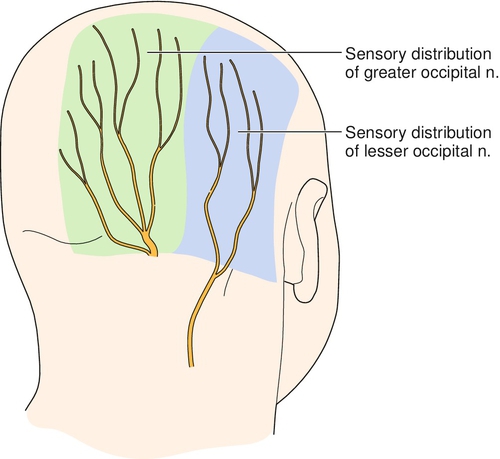

The greater occipital nerve innervates the posterior skull from the suboccipital area to the vertex. It is formed from the medial (sensory) branch of the posterior division of the second cervical nerve [8]. It emerges between the atlas and lamina of the axis below the oblique inferior muscle and then ascends obliquely on this muscle between it and the semispinalis muscle [8]. The course of the greater occipital nerve does not appear to differ in men and women [12]. The lesser occipital nerve forms from the medial (sensory) branch of the posterior division of the third cervical nerve, ascends like the greater occipital nerve, and pierces the splenius capitis and trapezius muscles just medial to the greater occipital nerve [8]. It ascends along the scalp to reach the vertex, where it provides sensory fibers to the area of the scalp lateral to the greater occipital nerve.

The roots of the first two cervical nerves are not protected posteriorly by pedicles and facets because of the unique articulation of the atlas and axis relative to the rest of the spinal column. Thus, the first two cervical nerves are relatively vulnerable to injury. The joint between the atlas and occiput, between which the first cervical nerve emerges, is relatively immobile compared with the lower C1-C2 articulation. Thus the C2 nerve root emerges unprotected through a highly mobile joint, and this may explain the predominance of greater occipital nerve involvement in occipital neuralgia [13].

Symptoms

Although occipital neuralgia is defined by the International Headache Society as a paroxysmal headache, some patients complain of continuous pain [2]. In continuous occipital neuralgia, the headaches may be further classified as acute or chronic.

Paroxysmal occipital neuralgia describes pain occurring only in the distribution of the occipital nerve. The attacks are generally unilateral, and the pain is sudden and severe. The patient may describe the pain as sharp, twisting, a dagger thrust, or an electric shock. The pain rarely demonstrates a burning characteristic. Although single flashes of pain may occur, multiple attacks are more frequent. The attacks may occur spontaneously or be provoked by specific maneuvers applied to the back of the scalp or neck regions, such as brushing the hair or moving the neck [11].

Acute continuous occipital neuralgia often has an underlying cause. Exposure to cold is a common trigger [14]. The attacks last for many hours and are typically devoid of radiating symptoms (e.g., trigger zones to the face). The entire episode of neuralgia can continue up to 2 weeks before remission.

In chronic continuous occipital neuralgia, the patient may experience painful attacks that last for days to weeks. These attacks are generally accompanied by localized spasm of the cervical or occipital muscles. The reported pain originates in the suboccipital region up to the vertex and radiates to the frontotemporal region. Radiation to the orbital region is also common. Sensory triggers to the face or skull can initiate a painful episode. Similarly, pain may increase with pressure of the head on a pillow. Prolonged abnormal fixed postures that occur in reading or sleeping positions and hyperextension or rotation of the head to the involved side may provoke the pain. The pain may be bilateral, although the unilateral pattern is more common. Often, a previous history of cervical or occipital trauma or arthritic disease of the cervical spine is obtained. On occasion, patients may report other autonomic symptoms concurrently, such as nausea, vomiting, photophobia, diplopia, ocular and nasal congestion, tinnitus, and vertigo [11]. Severe ocular pain has also been described, as have symptoms in other distributions of the trigeminal nerve [9,10,12,13]. Convergence of sensory input from the upper cervical nerve roots into the trigeminal nucleus may explain this phenomenon [13]. Occipital neuralgia may occur in combination with other types of headaches. For example, one study found concurrent migraine in 20 of 35 consecutive patients presenting with occipital neuralgia [14].

Physical Examination

On examination, pain is generally reproduced by palpation of the greater and lesser occipital nerves. Allodynia or hyperalgesia may be present in the nerve distribution. Myofascial pain may be present in the neck or shoulders. Pain may limit cervical range of motion. Neurologic examination findings of the head, neck, and upper extremities are generally normal.

Entrapment of the nerve near the cervical spine may result in increased symptoms during flexion, extension, or rotation of the head and neck. Compression of the skull on the neck (Spurling maneuver), especially with extension and rotation of the neck to the affected side, may reproduce or increase the patient’s pain if cervical degenerative disease is the cause of the neuralgia [11]. Pressure over both the occipital nerves along their course in the neck and occiput or pressure on the C2-C3 facet joints should cause an exacerbation of pain in such patients, at least when the headache is present. Even if the actual pathologic process is in the cervical spine, tenderness over the occipital nerve at the superior nuchal line is usually present.

Functional Limitations

In general, there are no neurologic deficits from occipital neuralgia. However, the pain from this entity may result in significant limitations in activities of daily living. During exacerbations, patients may have significant functional limitations, including insomnia, loss of work time, and inability to perform physical activity or to drive a vehicle. Tasks that involve the cervical spine or upper extremities, such as talking on the telephone, working at the computer, reading a book, cooking, gardening, and driving, may be painful and limited.

Diagnostic Studies

The diagnosis of occipital neuralgia is generally made clinically on the basis of history and physical examination. Imaging may help confirm the diagnosis when there is an anatomic cause. Diagnostic local anesthetic nerve blocks may be required for a definitive diagnosis to be obtained; these blocks are done with or without the addition of corticosteroid [5,8,11]. The relief of pain after a diagnostic local anesthetic block of the greater and lesser occipital nerves is generally confirmatory of the diagnosis of occipital neuralgia.

In addition, magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography of the cervical spine should be performed to rule out an anatomic cause, such as tumor, vascular malformation, infection, or spondylotic arthritis, that may be compressing the medial (sensory) branches of C2-C3 [15]. Radiographs may be obtained to rule out gross abnormalities as an initial screening test but will not generally provide the level of detail needed for diagnostic purposes. Single-photon emission computed tomography and positron emission tomography are being increasingly used for diagnosis and treatment of certain headache syndromes and may be useful in occipital neuralgia if there is functional pathologic change involved or in trying to distinguish between occipital neuralgia and cluster or migraine headache [13]. Radiologic degenerative changes of the cervical spine do not necessarily correlate with the patient’s symptoms and examination findings, but C2-C3 arthritic changes in the absence of other gross or radiographic abnormalities may explain the etiology. Other rare causes of occipital neuralgia reported in the literature include upper respiratory tract infection [16], herpes zoster infection or postherpetic neuralgia [17], myelitis [18], hypermobile C1 vertebra [19], and giant cell arteritis [20,21]. In patients with unilateral headaches in the distribution of the greater occipital nerve, ultrasonography can show enlargement of the ipsilateral nerve compared with the uninvolved contralateral nerve and thus lend further evidence to the diagnosis of occipital neuralgia [22].

Treatment

Initial

Treatments that may help with pain from occipital neuralgia include heat or cold therapy, massage, avoidance of excessive cervical spine flexion-extension or rotation, acupuncture, and application of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation.

Pharmacologic therapy with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or acetaminophen as well as other analgesics may be used. Tricyclic antidepressants, anticonvulsants, and muscle relaxants may also prove useful. Anticonvulsants such as carbamazepine, gabapentin, and pregabalin have been used for neuropathic pain with good results. Certain patients with comorbid psychological stressors may have pain complaints out of proportion to physical examination findings and should have their psychological symptoms treated with appropriate medications and psychological or cognitive-behavioral therapy.

Patients will often benefit from adaptive equipment at home and work, such as a telephone earset or bookstand. It is also important to determine whether patients are using bifocal glasses and whether adjusting the neck to use these glasses is contributing to the condition.

Rehabilitation

The incorporation of stretching and strengthening exercises for the paracervical and periscapular muscles may be appropriate for the patient with subacute or chronic occipital neuralgia, particularly if the condition is provoked by cervical spine or trunk movement. Postural training and relaxation exercises should be incorporated into the exercise regimen. Principles of ergonomics should be addressed if work site activity is limited by pain exacerbations (e.g., use of a telephone headset, document holder) [11]. An ergonomic workstation evaluation may be beneficial.

Manual therapy, including spinal manipulation and spinal mobilization, has been used to treat patients with cervicogenic headaches. A review of trials done with spinal manipulation for cervicogenic headache revealed two with positive results regarding headache intensity, headache duration, and medication intake [23]. Only one trial showed a decrease in headache frequency. There is clearly a need for more well designed randomized controlled trials to evaluate these therapies [24]. Any spinal manipulation should be done with caution because there are serious risks if it is improperly performed [25]. Anecdotal reports support a trial of cervical traction in some cases [11].

Procedures

Blockade of the greater or lesser occipital nerve with a local anesthetic is diagnostic and therapeutic (Fig. 105.2). Pain relief can vary from hours to months. In general, at least 50% of patients will experience more than 1 week of relief after one injection. Isolated pain relief for more than 17 months has been reported after a series of five blocks [7]. The addition of a cortisone preparation is controversial, but it may provide additional benefit [3]. Botulinum toxin A injection into the greater occipital nerve has also been described [3], but the evidence is limited. Its use is currently ranked as grade C, the weakest strength recommendation [26]. Classically, landmark techniques have been used in occipital nerve blockade. Ward [27] described one such blind technique wherein the greater occipital nerve is found medial to the occipital artery along the superior nuchal line. Nerve stimulator–guided blocks [28] and computed tomography–guided blocks [6] have also been described. An ultrasound-guided technique was recently demonstrated [29] and postulated as superior to traditional landmark techniques in light of known variation of the greater occipital nerve [30], but clinical studies have not confirmed this presumption.

Dorsal rhizotomy of C1, C2, C3, and C4 has been described; about 71% to 77% of patients report significant benefit [7,25–27]. Before dorsal rhizotomy, local anesthetic blockade of the suspected medial (sensory) branches should be performed for diagnostic purposes.

Pulsed radiofrequency to the culprit occipital nerve was shown to improve symptoms for 6 months or more [31]. A more recent report demonstrated benefit from pulsed radiofrequency in a significant portion of patients with treatment-refractory occipital neuralgia [32].

Surgery

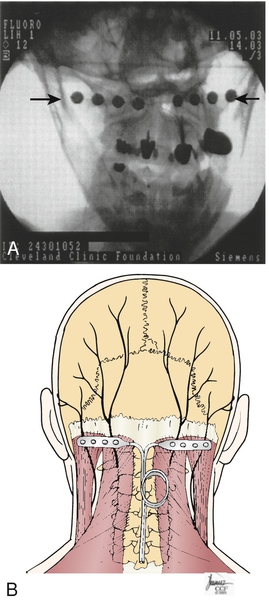

One should consider surgical treatment after conservative therapy has failed, including but not limited to membrane stabilizers, tricyclic antidepressants, opioids, spinal manipulation, occipital nerve or cervical medial branch blocks, and partial posterior rhizotomy of C1-C3 [6]. Reversible interventions may be considered before destructive, irreversible surgical procedures [33]. In 1999, Weiner and Reed described successful treatment of occipital neuralgia with neurostimulation, whereby subcutaneous implantation of electrical leads in the suboccipital region modulates afferent pain nociceptive fibers to decrease the transmission of painful impulses. This is thought to occur through the gate control theory of pain or possibly through modulation of neurotransmitters in the central nervous system [34] (Fig. 105.3). A variety of surgical procedures for occipital neuralgia have been proposed, such as neurectomy, C1-C2 decompression, C2 ganglionectomy, and occipital nerve stimulation. The rate of meaningful pain relief from ganglionectomy has been reported to be 60% to 67% [35,36].

Surgical release of the inferior oblique muscles has been described as a potential treatment of occipital neuralgia, particularly when compression of the nerve by this muscle is suspected. In a small, retrospective study of 10 patients, the average visual analog score for pain decreased from 8 of 10 to 2 of 10 after the procedure [37]. Dorsal root entry zone lesioning has also been reported for occipital neuralgia [38].

Potential Disease Complications

Occipital neuralgia is generally a self-limited disease, but it may progress in some cases to a chronic intractable pain syndrome. In refractory cases, it is critical to rule out more ominous conditions. Patients involved in litigation or who have psychosocial stresses or vocational disputes may have a poorer outcome.

Potential Treatment Complications

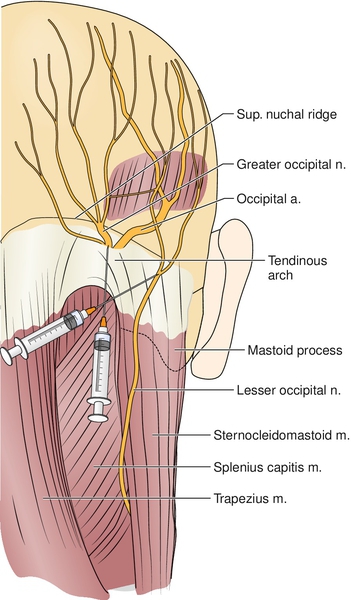

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have a number of well-established side effects, as do tricyclic antidepressants (Table 105.1). The anesthetic block of the greater or lesser occipital nerve is considered relatively safe [39]. Contraindications to this block include coagulopathy and current infection. Potential complications include bleeding, infection, nerve injury, seizure from intravascular injection of local anesthetic, and headache exacerbation. Care must be taken not to puncture the posterior occipital artery. If the artery is punctured, pressure should be applied vigorously.