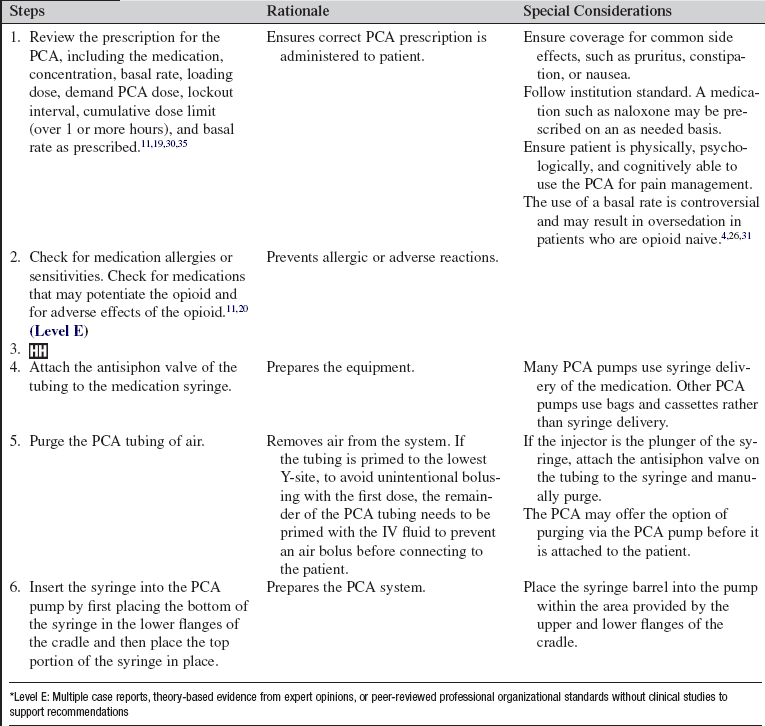

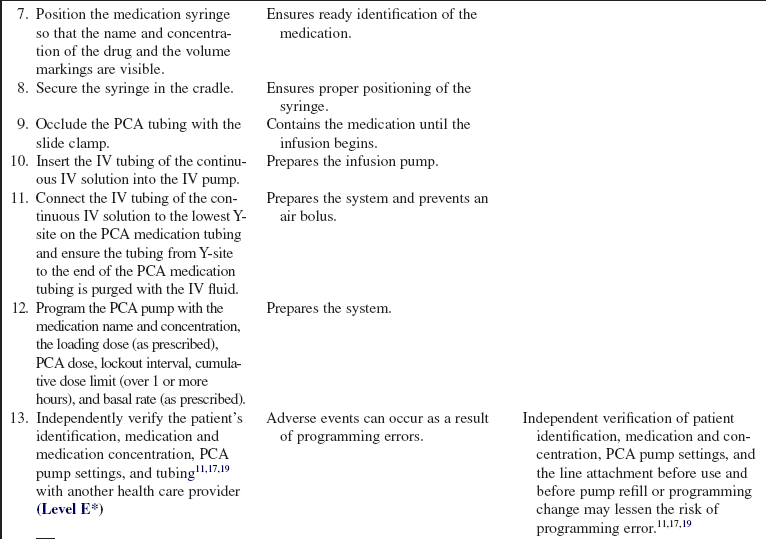

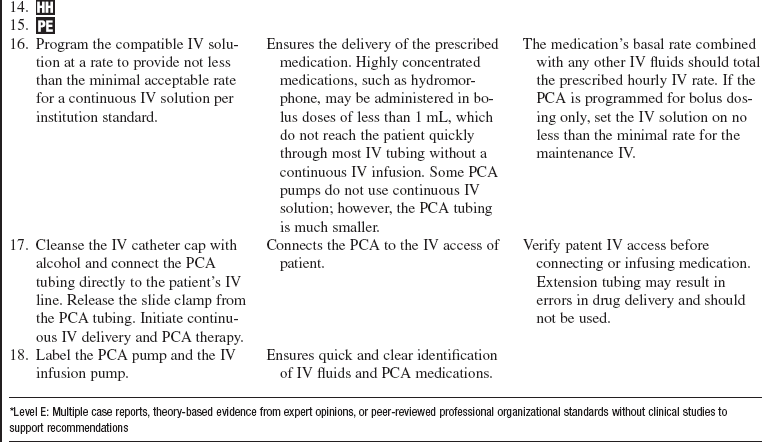

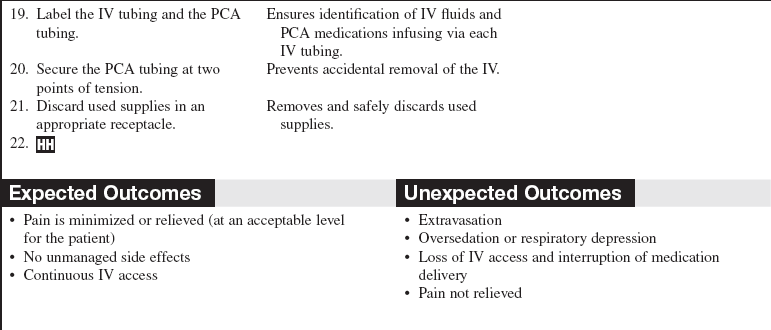

Patient-Controlled Analgesia

PREREQUISITE NURSING KNOWLEDGE

• Pain is an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience that arises from actual or potential tissue damage or is described in terms of such damage.1 According to the National Institutes of Health, more Americans are affected by pain than by diabetes, heart disease, and cancer combined.28

• The most common reason for unrelieved pain in hospitals is the failure of staff to routinely and adequately assess pain and pain relief.1

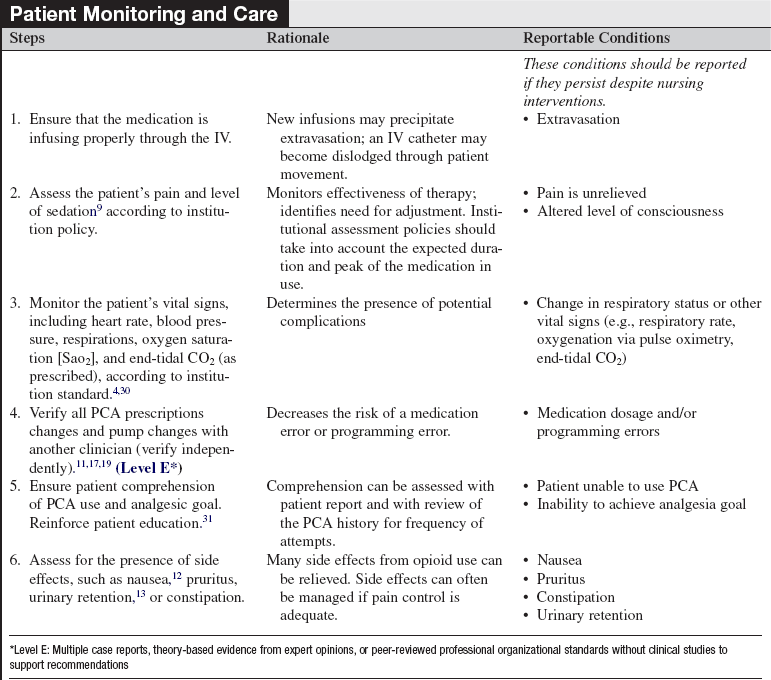

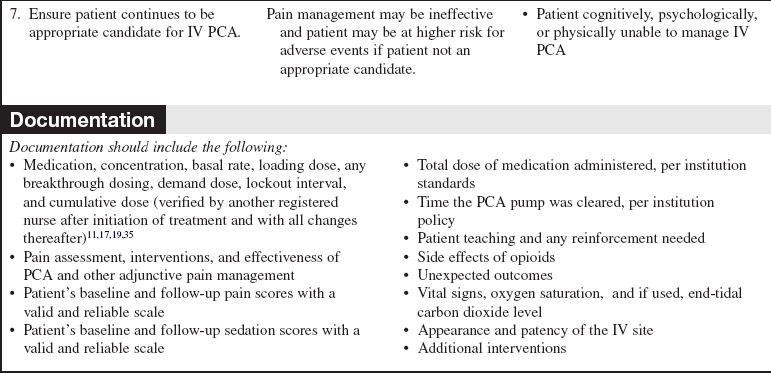

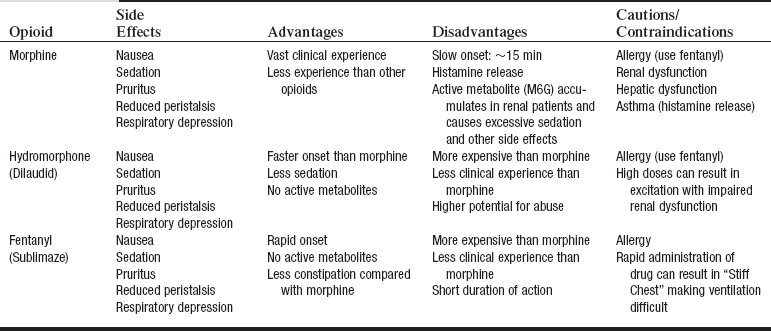

• Additional perceived barriers to adequate pain management are poor pain assessment, patient reluctance to report pain and take analgesics, and physician reluctance to prescribe opioids.1 Tables 102-1 and 102-2 list guidelines for dosing and considerations for selection of opioids.

Table 102-1

*Typical concentrations are listed in parentheses.

(Miaskowski C, Blair M, Chou R, et al: Principles of analgesic use in the treatment of acute pain and cancer pain, ed 6, Glenview, IL, 2008, American Pain Society, 42).

Table 102-2

Patient Controlled Analgesia: Considerations in Opioid Selection

(Institute for Safe Medication Practices: Patient-controlled analgesia: making it safer for patients, Horsham, PA, 2006, Institute for Safe Medication Practices.)

• Unrelieved postoperative pain may result in clinical and psychologic changes, an increase in morbidity and mortality, an increase in costs, and a decrease in quality of life. Negative clinical outcomes related to ineffective pain management for patients after surgery include deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, coronary ischemia, myocardial infarction, pneumonia, poor wound healing, impairment of the immune system, insomnia, and negative emotions.25 Unrelieved pain may delay recovery and prolong hospital stays.1,3

• The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) urges healthcare professionals to accept the patient’s self-report as “the single most reliable indicator of the existence and intensity” of pain.1

• Studies and meta-analyses have shown an increase in patient satisfaction with pain management and an improvement in pain control.5,18,23,34,38 Intravenous (IV) patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) may be used for both acute and chronic pain.26

• Intravenous PCA can be an effective method of pain relief for pediatric and adult patients.14,18,34,38 Table 102-1 lists dosing guidelines.

• Intravenous PCA can be administered as a continuous (basal) infusion along with patient-initiated boluses or as intermittent patient-initiated boluses exclusively.

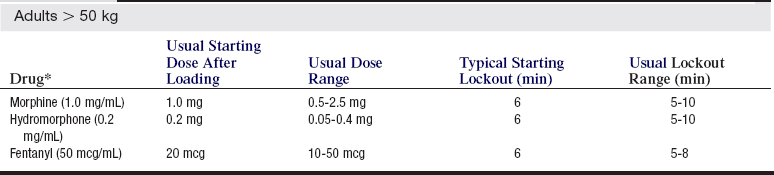

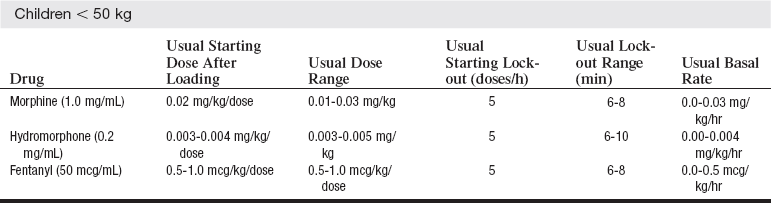

• Patient assessment at frequent, regular intervals (at least every 4 hours) should include an evaluation of the patient’s vital signs, sedation level with a valid and reliable scale, pain level with a valid and reliable scale, and common opioid side effects, such as pruritus, nausea,9,12 constipation, and urinary retention.13 Table 102-2 lists side effects associated with PCA opioids. Patients need more frequent assessments during the first 24 hours after initiation of IV PCA and during the night.10,11,14,19 Systematic evaluation of agitation and pain can lead to a reduction in pain levels and agitation.9

• PCA pump settings should be confirmed at regular intervals.10,11,19 See Box 102-1 for common terms used when administering patient-controlled analgesia. Adverse events during IV PCA may include respiratory depression and hypoxemia. Opioid anatagonists should be readily available.

• Adjunctive medications can be used to improve pain management7,14,15,27,39 or to improve opioid side effects.7,15,23,24

• The Joint Commission does not support PCA by proxy (someone other than the patient pushing the PCA button) on the recommendation of the Institute of Safe Medication Practices (ISMP). According to ISMP, patients have experienced oversedation, increased respiratory depression, and death from PCA by proxy.11,19,21

• PCA by authorized user (typically nurse or designated family member of patient) is a potential alternative to PCA by proxy. Healthcare institutions that use PCA by authorized user need to have the following in place before this practice is initiated.2,11,19,21,22,37,41

Policies that guide the practice, including the patient population

Policies that guide the practice, including the patient population

Definition of PCA by an authorized user

Definition of PCA by an authorized user

• Patients with an increased risk for complications during IV PCA use include those with:

Age more than 65 years (greater incidence of desaturation)29

Age more than 65 years (greater incidence of desaturation)29

Morbid obesity (greater incidence of desaturation)8,29,36

Morbid obesity (greater incidence of desaturation)8,29,36

Sleep apnea or asthma8,11,20,36

Sleep apnea or asthma8,11,20,36

Concurrent medications that potentiate opiates (e.g., sedation)11,19

Concurrent medications that potentiate opiates (e.g., sedation)11,19

• Careful patient selection is imperative for effective pain management. Patients who may be poor candidates for PCA include the following:

Anyone with cognitive abilities that prohibit understanding and following directions for IV PCA (e.g., infants, young children, patients with a decreased level of consciousness or with developmental disabilities)11,19

Anyone with cognitive abilities that prohibit understanding and following directions for IV PCA (e.g., infants, young children, patients with a decreased level of consciousness or with developmental disabilities)11,19

Anyone without the physical ability to push the PCA button that controls the dose administration11,19

Anyone without the physical ability to push the PCA button that controls the dose administration11,19

Anyone with a psychologic reason that prohibits using the PCA button for pain management (e.g., psychologic disability, refusal to operate the PCA administration button)11,19

Anyone with a psychologic reason that prohibits using the PCA button for pain management (e.g., psychologic disability, refusal to operate the PCA administration button)11,19

• Patients can have as effective or better pain control with epidural analgesia than with IV PCA after various surgical procedures.6,16,32,33,40

• A number of medication errors have been reported with IV PCA. Factors associated with errors include improper patient selection, inadequate monitoring, inadequate patient education, medication product mix-ups, programming errors, PCA by proxy, inadequate medical and nursing staff education, prescription errors, and PCA pump design flaws.11,17,19

• PCA is available in various routes, including IV, epidural (patient-controlled epidural analgesia [PCEA]; see Procedure 101), subcutaneous, peripheral nerve catheter (see Procedure 103), oral, intranasal, and transdermal.14,15,25,26,31 The focus of this procedure is IV PCA.

EQUIPMENT

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION

• Review an appropriate pain rating scale with the patient. The healthcare provider and patient need to establish a mutually agreeable pain level goal.  Rationale: Review ensures that the patient understands the pain rating scale and enables the nurse to obtain a baseline assessment. Establishing a pain level goal allows the healthcare provider to know an acceptable goal for pain management.

Rationale: Review ensures that the patient understands the pain rating scale and enables the nurse to obtain a baseline assessment. Establishing a pain level goal allows the healthcare provider to know an acceptable goal for pain management.

• Review the principles of PCA use with the patient and family members.31 If a basal rate has been prescribed, inform the patient that pain medication will be infusing at all times. Explain that if the pain is not relieved with the steady dose, extra medicine can be delivered. Be sure the patient understands what the lockout interval is. If the patient’s pain needs are not met, the dosage can and will be changed to meet those needs.  Rationale: This review may reduce anxiety and preconceptions about PCA use.

Rationale: This review may reduce anxiety and preconceptions about PCA use.

• Intravenous PCA is designed for the patient to administer the pain medication. In most circumstances, the patient should be the only one to deliver the demand dose. The ISMP and The Joint Commission do not support PCA by proxy because of adverse events, such as oversedation, respiratory depression, cardiopulmonary arrest, and deaths that have occurred with PCA by proxy.11,19,20,21  Rationale: The patient should remain alert enough to administer his or her own dose. A safeguard to oversedation is that a patient cannot administer additional medication doses if sedated.

Rationale: The patient should remain alert enough to administer his or her own dose. A safeguard to oversedation is that a patient cannot administer additional medication doses if sedated.

• Instruct the patient and family members to report common side effects, such as oversedation, pruritus, nausea or vomiting, constipation, or urinary retention.  Rationale: Side effects are identified by the patient and family.

Rationale: Side effects are identified by the patient and family.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT AND PREPARATION

Patient Assessment

• Assess the patient’s ability to properly use IV PCA as a method for pain management.  Rationale: The patient will not achieve adequate pain management if unable to use the PCA.

Rationale: The patient will not achieve adequate pain management if unable to use the PCA.

• Assess the patient’s pain and document the intensity, location, and characteristics.2,3,27  Rationale: A baseline assessment permits an accurate evaluation of the efficacy of the PCA.

Rationale: A baseline assessment permits an accurate evaluation of the efficacy of the PCA.

• Assess the patient’s level of consciousness with use of a sedation scale.28,41  Rationale: Sedation generally precedes respiratory depression; a patient who is less alert should be closely monitored if PCA is prescribed.

Rationale: Sedation generally precedes respiratory depression; a patient who is less alert should be closely monitored if PCA is prescribed.

• Review the patient’s medication allergies.  Rationale: Review of medication allergies before administration of a new medication decreases the chances of an allergic reaction.

Rationale: Review of medication allergies before administration of a new medication decreases the chances of an allergic reaction.

Patient Preparation

• Verify correct patient with two identifiers.  Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

• Ensure that the patient understands the teaching. Answer questions as they arise, and reinforce information as needed.31  Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

• Obtain IV access or ensure patency of the IV.  Rationale: Analgesia is delivered intravenously.

Rationale: Analgesia is delivered intravenously.

References

![]() 1. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Acute Pain Management Guideline Panel: . Clinical practice guidelines acute pain managementoperative or medical -procedure and trauma, AHCPR pub. 92-0032. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Public Health Service, US Department of Health and -Human Services, Rockville, MD, 1992.

1. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Acute Pain Management Guideline Panel: . Clinical practice guidelines acute pain managementoperative or medical -procedure and trauma, AHCPR pub. 92-0032. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Public Health Service, US Department of Health and -Human Services, Rockville, MD, 1992.

![]() 2. Anghelescu, DL, Burgoyne, LL, Oakes, LL, et al. The safety of patient-controlled analgesia by proxy in pediatric oncology patients. Anesth Analg. 2005; 101:1623–1627.

2. Anghelescu, DL, Burgoyne, LL, Oakes, LL, et al. The safety of patient-controlled analgesia by proxy in pediatric oncology patients. Anesth Analg. 2005; 101:1623–1627.

![]() 3. Apfelbaum, JL, Chen, C, Mehta, SS, et al, Postoperative pain experience. results from a national survey suggest postoperative pain continues to be undermanaged. Anesth Analg 2003; 97:534–540.

3. Apfelbaum, JL, Chen, C, Mehta, SS, et al, Postoperative pain experience. results from a national survey suggest postoperative pain continues to be undermanaged. Anesth Analg 2003; 97:534–540.

![]() 4. Ashburn, MA, Caplan, RA, Carr, DB, et al, Practice guidelines for acute pain management in the perioperative setting. an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Acute Pain Management. Anesthesiology 2004; 100:1573–1581.

4. Ashburn, MA, Caplan, RA, Carr, DB, et al, Practice guidelines for acute pain management in the perioperative setting. an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Acute Pain Management. Anesthesiology 2004; 100:1573–1581.

![]() 5. Ballantyne, JC, Carr, DB, Chalmers, TC, et al, Postoperative patient-controlled analgesia. a meta-analysis of initial randomized control trials. J Clin Anesth 1993; 5:182–193.

5. Ballantyne, JC, Carr, DB, Chalmers, TC, et al, Postoperative patient-controlled analgesia. a meta-analysis of initial randomized control trials. J Clin Anesth 1993; 5:182–193.

6. Bauer, C, Hentz, JG, Ducrocq, X, et al, Lung function after lobectomy. a randomized, double-blinded trial comparing thoracic epidural ropivacaine/sufentanil and intravenous morphine for patient-controlled analgesia. Anesth Analg 2007; 105:238–244.

7. Capdevila, X, Dadure, C, Bringuier, S, et al, Effect of -patient-controlled perineural analgesia on rehabilitation and pain after ambulatory orthopedic surgery. a multicenter randomized trial. Anesthesiology 2006; 105:566–573.

![]() 8. Cashman, JN, Dolin, SJ, Respiratory and haemodynamic effects of acute postoperative pain management. evidence from published data. Br J Anesth 2004; 93:212–223.

8. Cashman, JN, Dolin, SJ, Respiratory and haemodynamic effects of acute postoperative pain management. evidence from published data. Br J Anesth 2004; 93:212–223.

9. Chanques, G, Jaber, S, Barbotte, E, et al. Impact of systematic evaluation of pain and agitation in an intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2006; 34:1691–1699.

![]() 10. Cohen, MR, Smetzer, J. Patient-controlled analgesia safety issues. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2005; 19:45–50.

10. Cohen, MR, Smetzer, J. Patient-controlled analgesia safety issues. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2005; 19:45–50.

11. Cohen, MR, Weber, RJ, Moss, J, Patient-controlled analgesia. making it safer for patients. 2006. Institute for Safe Medication Practices. Text available at: Horsham, PA. http://www.ismp.org/profdevelopment/PCAMonograph.pdf

![]() 12. Culebras, X, Corpataux, J, Gaggero, G, et al, The antiemetic efficacy of droperidol added to morphine patient-controlled analgesia. a randomized controlled multicenter dose-finding study. Anesth Analg 2003; 97:816–821.

12. Culebras, X, Corpataux, J, Gaggero, G, et al, The antiemetic efficacy of droperidol added to morphine patient-controlled analgesia. a randomized controlled multicenter dose-finding study. Anesth Analg 2003; 97:816–821.

13. Gallo, S, DuRand, J, Pshon, N. A study of naloxone effect on urinary retention in the patient receiving morphine patient-controlled analgesia. Orthop Nurs. 2008; 27:111–115.

![]() 14. Grass, JA. Patient-controlled analgesia. Anesth Analg. 2005; 101:S44–S61.

14. Grass, JA. Patient-controlled analgesia. Anesth Analg. 2005; 101:S44–S61.

15. Grond, S, Hall, J, Spacek, A, et al. Iontophoretic transdermal system using fentanyl compared with patient-controlled intravenous analgesia using morphine for postoperative pain management. Br J Anaesth. 2007; 98(6):806–815.

16. Gupta, A, Fant, F, Axelsson, K, et al, Postoperative analgesia after radical retropubic prostatectomy. a double-blind comparison between low thoracic epidural and patient-controlled intravenous analgesia. Anesthesiology 2006; 105:784–793.

17. Hicks, RW, Sikirica, V, Nelson, W, et al. Medication errors involving patient-controlled analgesia. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008; 65:429–440.

18. Hudcova, J, McNicol, ED, Quah, CS, et al. Patient controlled opioid analgesia versus conventional opioid analgesia for postoperative pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 4, 2006. [CD003348].

![]() 19. Institute for Safe Medication Practices, Safety issues with patient-controlled analgesia. part 1how errors occur,. Institute for Safe Medication Practices, Horsham, PA, 2003.. http://www.ismp.org/newsletters/acutecare/articles/20030710.asp [accessed September 28, 2009, from].

19. Institute for Safe Medication Practices, Safety issues with patient-controlled analgesia. part 1how errors occur,. Institute for Safe Medication Practices, Horsham, PA, 2003.. http://www.ismp.org/newsletters/acutecare/articles/20030710.asp [accessed September 28, 2009, from].

![]() 20. Institute for Safe Medication Practices, Safety issues with patient-controlled analgesia. part IIhow to prevent errors,. Institute for Safe Medication Practices, Horsham, PA, 2003.. http://www.ismp.org/newsletters/acutecare/articles/20030724.asp [accessed September 28, 2009, from].

20. Institute for Safe Medication Practices, Safety issues with patient-controlled analgesia. part IIhow to prevent errors,. Institute for Safe Medication Practices, Horsham, PA, 2003.. http://www.ismp.org/newsletters/acutecare/articles/20030724.asp [accessed September 28, 2009, from].

![]() 21. Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, Sentinel event alert. patient controlled analgesia by proxy,. Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, Oakbrook Terrace, IL, 2004.. www.jointcommission.org/sentinelevents/sentineleventalert/sea_33.htm

21. Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, Sentinel event alert. patient controlled analgesia by proxy,. Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, Oakbrook Terrace, IL, 2004.. www.jointcommission.org/sentinelevents/sentineleventalert/sea_33.htm

22. Krane, EJ, Patient-controlled analgesia. proxy-controlled analgesia. Anesth Analg 2008; 107:15–17.

![]() 23. Lee, Y, Lai, HY, Lin, PC, et al, A dose ranging study of dexamethasone for preventing patient-controlled analgesia-related nausea and vomiting. a comparison of droperidol with saline. Anesth Analg 2004; 98:1066–1071.

23. Lee, Y, Lai, HY, Lin, PC, et al, A dose ranging study of dexamethasone for preventing patient-controlled analgesia-related nausea and vomiting. a comparison of droperidol with saline. Anesth Analg 2004; 98:1066–1071.

![]() 24. Maxwell, LG, Kaufmann, SC, Bitzer, S, et al, The effects of a small-dose naloxone infusion on opioid-induced side effects and analgesia in children and adolescents treated with intravenous patient-controlled analgesia. a double-blind, prospective, randomized, controlled study. Anesth Analg 2005; 100:953–958.

24. Maxwell, LG, Kaufmann, SC, Bitzer, S, et al, The effects of a small-dose naloxone infusion on opioid-induced side effects and analgesia in children and adolescents treated with intravenous patient-controlled analgesia. a double-blind, prospective, randomized, controlled study. Anesth Analg 2005; 100:953–958.

![]() 25. Miaskowski, C. Patient-controlled modalities for acute postoperative pain management. J Perianesth Nurs. 2005; 20:255–267.

25. Miaskowski, C. Patient-controlled modalities for acute postoperative pain management. J Perianesth Nurs. 2005; 20:255–267.

26. Miaskowski, C, Bair, M, Chou, R, et al. Principles of analgesic use in the treatment of acute pain and cancer pain,. Glenview, IL: American Pain Society; 2008.

27. Michelet, P, Guervilly, C, Hélaine, A, et al, Adding ketamine to morphine for patient-controlled analgesia after thoracic surgery. influence on morphine consumption, respiratory function, and nocturnal desaturation. Br J Anaesth 2007; 99:396–403.

28. National Institutes of Health, Pain management. fact sheet. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, 2007.

29. Overdyk, FJ, Carter, R, Maddox, RR, et al. Continuous oximetry/capnometry monitoring reveals frequent desaturation and bradypnea during patient-controlled analgesia. Anesth Analg. 2007; 105:412–418.

![]() 30. Pasero, C, McCaffery, M. Safe use of a continuous infusion with IV PCA. J Perianesth Nurs. 2004; 19:42–45.

30. Pasero, C, McCaffery, M. Safe use of a continuous infusion with IV PCA. J Perianesth Nurs. 2004; 19:42–45.

31. Pasero, C, McCaffery, M. Orthopaedic postoperative pain management. J Perianesth Nurs. 2007; 22:160–172.

32. Roussier, M, Mahul, P, Pascal, J, et al. Patient-controlled cervical epidural fentanyl compared with patient-controlled i. v. fentanyl for pain after pharyngolaryngeal surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2006; 96:492–496.

33. Schenk, MR, Putzier, M, Kugler, B, et al, Postoperative analgesia after major spine surgery. patient-controlled epidural analgesia versus patient-controlled intravenous analgesia. Anesth Analg 2006; 103:1311–1317.

34. Schiessl, C, Gravou, C, Zernikow, B, et al. Use of patient-controlled analgesia for pain control in dying children. Support Care Cancer. 2008; 16:531–536.

35. St. Marie B. Pain management. In: Weinstein SM, ed. Plumer’s principles and practice of intravenous therapy. ed 8. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006:576–607.

![]() 36. Stone, JG, Cozine, KA, Wald, A. Nocturnal oxygenation during patient-controlled analgesia. Anesth Analg. 1999; 89:104–110.

36. Stone, JG, Cozine, KA, Wald, A. Nocturnal oxygenation during patient-controlled analgesia. Anesth Analg. 1999; 89:104–110.

37. Voepel-Lewis T, Marinkovic, A, Kostrzewa, A, et al. The prevalence of and risk factors for adverse events in children receiving patient-controlled analgesia by proxy or patient-controlled analgesia after surgery. Anesth Analg. 2008; 107:70–75.

![]() 38. Walder, B, Schafer, M, Henzi, I, Tramèr, MR, Efficacy and safety of patient-controlled opioid analgesia for acute postoperative pain. a quantitative systematic review. Acta Anaesth Scand 2001; 45:795–804.

38. Walder, B, Schafer, M, Henzi, I, Tramèr, MR, Efficacy and safety of patient-controlled opioid analgesia for acute postoperative pain. a quantitative systematic review. Acta Anaesth Scand 2001; 45:795–804.

39. Webb, AR, Skinner, BS, Leong, S, et al, The addition of a small-dose ketamine infusion to tramadol for postoperative analgesia. a double-blinded, placebo-controlled, randomized trial after abdominal surgery. Anesth Analg 2007; 104:912–917.

![]() 40. Werawatganon, T, Charuluxanun, S. Patient controlled intravenous opioid analgesia versus continuous epidural analgesia for pain after intra-abdominal surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1, 2005. [CD004088].

40. Werawatganon, T, Charuluxanun, S. Patient controlled intravenous opioid analgesia versus continuous epidural analgesia for pain after intra-abdominal surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1, 2005. [CD004088].

41. Wuhrman, E, Cooney, MF, Dunwoody, CJ, et al, Authorized and unauthorized (“PCA by proxy”) dosing of analgesic infusion pumps. position statement with clinical practice recommendations. Pain Manag Nurs 2006; 8:4–11.

Helfand, M, Freeman, M, Assessment and management of acute pain in adult medical inpatients. a systematic review. Pain Med 2009; 10:1183–1199.

Hicks, RW, Heath, WM, Sikirica, V, et al. Medication -errors involving patient-controlled analgesia. Jt Comm -J Qual Patient Saf. 2008; 43:734–742.

Kim, HS, Czuczman, GJ, Nicholson, WK, et al, Pain levels within 24 hours after UFE. a comparison of morphine -and fentanyl patient-controlled analgesia. Cardiovas Interv Radiol 2008; 31:1100–1107.

Leung, JM, Sands, LP, Paul, S, et al. Does postoperative -delirium limit the use of patient-controlled analgesia -in older surgical patients. Anesthesiology. 2009; 111:625–631.

Schein, JR, Hicks, RW, Nelson, WW, et al, Patient-controlled analgesia-related errors in the postoperative period. causes and prevention. Drug Safety 2009; 32:549–559.

Weitz, JW, Witkowski, TA, Viscusi, ER. new and emerging analgesics and analgesic technologies for acute pain management. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2009; 22:608–617.