CHAPTER 102

Headaches

Huma Sheikh, MD; Shivang Joshi, MD, MPH, BPharm; Elizabeth Loder, MD

Definition

The three major primary headache disorders are migraine, cluster, and tension-type headache [1]. Although all three syndromes are characterized by chronic, recurrent, and potentially disabling headaches, specific diagnosis is important because of differing natural history and treatment.

Headache disorders are classified according to criteria outlined in the International Classification of Headache Disorders, originally developed by the International Headache Society in 1988 and revised in 2004 [1]. The criteria are available online (www.ihs-headache.org) and are due to be revised soon [2]. However, changes to criteria for the three primary headache disorders are expected to be minor. Diagnosis of all but a few rare migraine subtypes remains clinical, based on the patient’s history and an examination that rules out secondary causes of headache (not covered in this chapter). The International Classification of Headache Disorders criteria were developed for research purposes and lack sensitivity when they are used in the clinical setting. Both migraine and tension-type headaches are more common in women than in men; cluster headache is generally a male disorder. Peak prevalence of migraine occurs during midlife, when it affects almost a quarter of all women and roughly 10% of men [3]. Recurrent headaches are not rare in children, but accurate diagnosis can be difficult because headache presentation in children varies from that in adults, and children may have difficulty describing the headache characteristics needed for a diagnosis to be made [4].

Migraine

Migraine is subclassified as migraine without aura (Table 102.1) and migraine with aura (Table 102.2). About 20% of patients have aura, usually preceding the headache, which consists of focal neurologic signs or symptoms that begin gradually and fade away within 30 to 60 minutes as the headache begins. The most common type of aura involves visual disturbances, typically an enlarging scotoma, but patients can also see shapes such as stars, zigzag lines, or other visual distortions, including field cuts and photopsias. Sensory or motor problems occur far less frequently. Blurry vision is usually not considered a part of aura. Migraine can also be classified as episodic or chronic (15 or more migraine headache days per month). Three gene mutations have been identified that are associated with a particular subtype of migraine with aura known as familial hemiplegic migraine. These genes influence the stability of neuronal cell membranes [5,6]. Some patients are able to identify triggers for their headache, including exertion, certain foods, and hormonal influences.

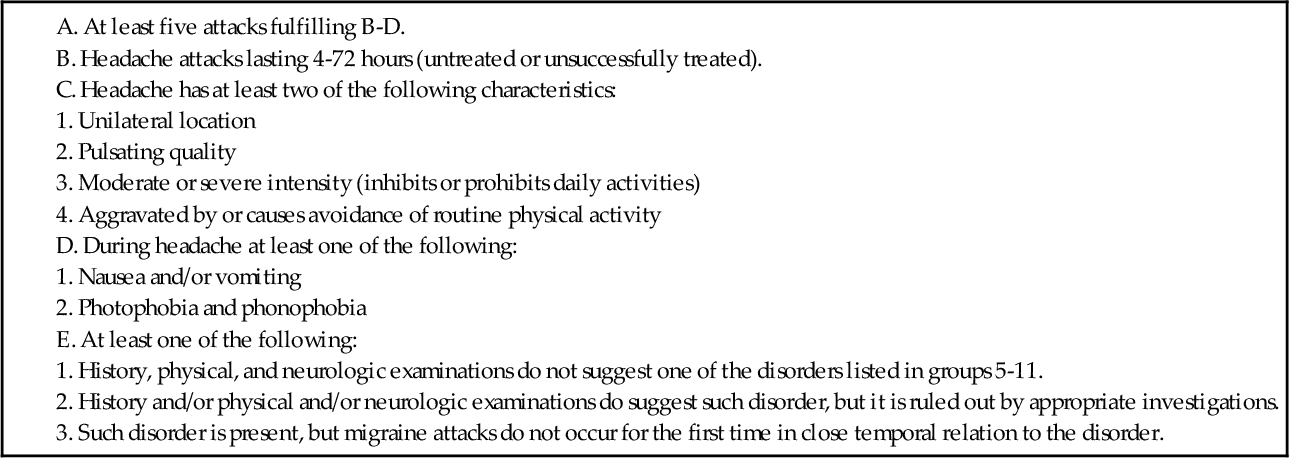

Table 102.1

Diagnostic Criteria for Migraine without Aura

A. At least five attacks fulfilling B-D.

B. Headache attacks lasting 4-72 hours (untreated or unsuccessfully treated).

C. Headache has at least two of the following characteristics:

2. Pulsating quality

3. Moderate or severe intensity (inhibits or prohibits daily activities)

4. Aggravated by or causes avoidance of routine physical activity

D. During headache at least one of the following:

2. Photophobia and phonophobia

E. At least one of the following:

2. History and/or physical and/or neurologic examinations do suggest such disorder, but it is ruled out by appropriate investigations.

3. Such disorder is present, but migraine attacks do not occur for the first time in close temporal relation to the disorder.

From Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders: 2nd edition. Cephalalgia 2004;24(Suppl 1):1-160.

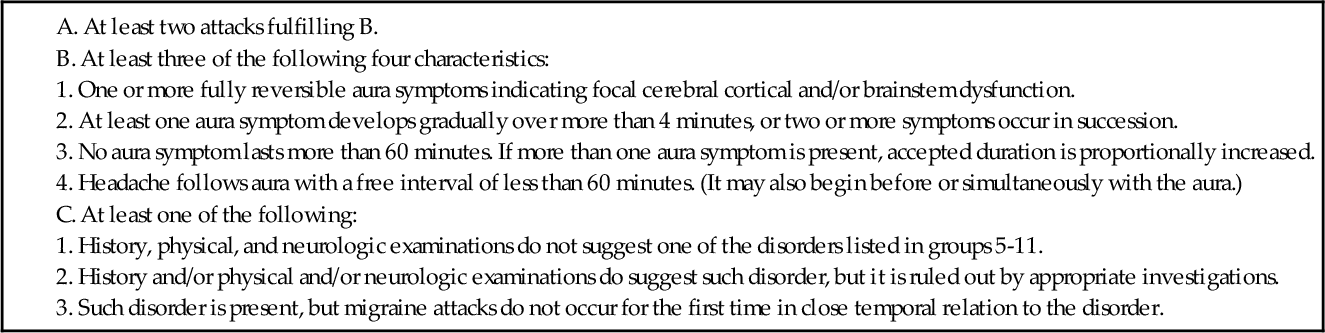

Table 102.2

Diagnostic Criteria for Migraine with Aura

A. At least two attacks fulfilling B.

B. At least three of the following four characteristics:

2. At least one aura symptom develops gradually over more than 4 minutes, or two or more symptoms occur in succession.

3. No aura symptom lasts more than 60 minutes. If more than one aura symptom is present, accepted duration is proportionally increased.

4. Headache follows aura with a free interval of less than 60 minutes. (It may also begin before or simultaneously with the aura.)

C. At least one of the following:

2. History and/or physical and/or neurologic examinations do suggest such disorder, but it is ruled out by appropriate investigations.

3. Such disorder is present, but migraine attacks do not occur for the first time in close temporal relation to the disorder.

From Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders: 2nd edition. Cephalalgia 2004;24(Suppl 1):1-160.

Cluster

Cluster headaches are strictly unilateral headaches that are far more common in men than in women, but the prevalence in the general population overall is approximately 0.1% [7]. The pain is sharp and steady, in contrast to the throbbing pain of migraine, and localized to the orbital area. Diagnostic criteria require the presence of at least one autonomic sign or symptom during the headache, such as ipsilateral conjunctival injection, lacrimation, rhinorrhea, ptosis, or miosis.

Cluster headache is so called because the headaches occur regularly in most cases, from one to eight times a day, during a period of 2 weeks to 3 months that is referred to as a cluster episode. The headaches then completely remit for months or years. In chronic cluster headache, there are no headache-free periods or remissions, or they are less than 2 weeks in duration [8]. Patients with cluster headache usually describe alcohol intolerance during the cluster episode and generally note intense restlessness during the headache.

Tension Type

Tension-type headaches can vary in length from 30 minutes to 7 days. They are typically bilateral, moderate in intensity, and described as a pressing, squeezing sensation that is not affected by physical activity. Associated symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting, photophobia, and phonophobia, are generally not present or are mild. Tension-type headache is subclassified as infrequent episodic if it occurs less than 1 day per month, frequent episodic if it occurs from 1 day to 14 days per month, and chronic with attacks occurring 15 days or more per month for at least 6 months [1]. Patients with tension-type headache typically do not spontaneously report symptoms other than headache. A diagnosis of migraine should be reexamined if multiple associated symptoms are reported, like nausea and photophobia, which are thought to be a part of the sympathetic activation that occurs with migraines.

Symptoms

In addition to the aforementioned symptoms that are required for diagnosis, many patients with migraine report prodromal symptoms: yawning; neck and shoulder muscle discomfort; excessive salivation; and changes in appetite, mood, sleep, gastrointestinal function, and urination. Some of these can start days before the actual headache. Postdromal symptoms in migraine include fatigue, exercise intolerance, and neck and shoulder muscle discomfort. If headaches progress untreated, 80% of patients eventually develop allodynia, defined as pain in response to stimuli that normally are nonpainful. Once allodynia develops, treatment may be less successful [9].

Physical Examination

The primary headache disorders are diagnosed by history. The major purpose of physical and neurologic examination is to rule out the presence of secondary headache disorders. Accordingly, the most important parts of the physical examination are funduscopic examination to exclude papilledema and neurologic examination to exclude focal deficits that might suggest a malignant neoplasm, vascular causes like stroke or hemorrhage, collagen vascular disease, or infectious cause of headaches, among others.

Interictally, the physical and neurologic examination findings will be normal in primary headache disorders, or if another disorder is identified, it must not be causally related to the primary headache. Subtle cerebellar signs, such as dysmetria and balance abnormalities, have been detected in migraineurs compared with normal controls, but these are generally not detectable in a typical examination [10].

If the patient is examined during a headache attack, the following points should be specifically noted.

• Patients experiencing cluster headache are physically restless, in contrast to migraine sufferers.

• Head banging and agitation are common [11]. Autonomic signs should be documented to confirm the diagnosis. Between attacks, persistent ptosis and conjunctival injection may occasionally be seen.

• Patients experiencing tension-type headache may appear uncomfortable but generally are not incapacitated.

• Neck, shoulder, and jaw tightness is common in patients with prolonged episodes of all primary headache types and does not necessarily represent the underlying cause of the headache. In most cases, these complaints will improve with appropriate treatment of the headache and do not need to be treated separately. There is no evidence that patients with tension-type headache have abnormally elevated muscle tension. In fact, electromyographic findings do not have diagnostic or treatment implications in migraine or tension-type headache [12]. Although biofeedback-assisted muscle relaxation is clearly of benefit in migraine and tension-type headache, it may exert its effect through mechanisms other than muscle relaxation.

Functional Limitations

Quality of life surveys and other data suggest that patients with primary headache disorders are more functionally impaired than is commonly appreciated [13]. Obviously, acute attacks of migraine and cluster headache prohibit function and generally require bed rest if untreated. Visual aura can render driving or other hazardous activities dangerous or even impossible. Tension-type headache does not generally prohibit activities but may inhibit them. Patients commonly report feeling that they are not functioning at “full capacity.” In many cases, severely affected patients report that fear and anxiety about possible attacks lead them to avoid, to cancel, or to decline work, social, and academic opportunities. Depression is a common comorbidity with poorly controlled headaches and also may lead to impaired function. The functional limitations imposed on many patients by nonspecific sedative treatments for migraine or by prophylactic treatments, which can cause fatigue, exercise intolerance, weight gain, and depression, are also underappreciated.

Diagnostic Studies

The primary headache disorders are clinical diagnoses, with the exception of the rare hemiplegic migraine syndromes. In general, imaging studies or laboratory tests are done to rule out secondary headache disorders, not to rule in primary disorders. With the exception of genetic testing for genes associated with familial hemiplegic migraine, there are currently no laboratory, genetic, or imaging markers that confirm a diagnosis of ordinary migraine with or without aura in individual patients. Biomarkers do exist that can distinguish subgroups of migraineurs, like those with hemiplegic migraine, from one another or from normal controls [14]. Some of the red flags to look out for that signal a secondary headache include change in pattern of headaches, headaches on awakening, any associated neurologic deficits, and headaches with onset in older age.

Treatment

Initial

Headache treatment consists of nonpharmacologic measures, lifestyle changes, and abortive treatment of acute attacks [15]. Another option, prophylactic treatment, in which daily medication is given to decrease the frequency and severity of headache episodes, is reserved for patients who do not obtain acceptable relief from abortive therapy or have more than two headache attacks a week. Although there is some overlap in treatment options among the various headache disorders, there are also important differences. In particular, cluster headache is often erroneously treated for years with migraine medication, to little or no avail [16].

Migraine

Lifestyle modification includes regular and adequate sleep and hydration, avoidance of excess caffeine, avoidance of missed meals, avoidance of alcohol (not a trigger for all migraine patients), and regular aerobic exercise. Although it is commonly advised, there is no scientific evidence that avoidance of chocolate, dairy products, or the myriad other dietary factors anecdotally implicated in migraine is helpful for the majority of patients with migraine. In the absence of good scientific evidence, it does not seem wise to promote food anxieties.

Nonpharmacologic treatment includes therapies such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, biofeedback-assisted relaxation, physical therapy, and acupuncture (although there is weak evidence of acupuncture’s benefit). Physical therapy has not been shown to be useful in a trial that compared physical therapy and medication for migraine with medication alone [17]. If physical therapy is used, it should be short term and focus on development of an aerobic or other exercise program rather than on passive therapeutic modalities. One study did suggest that aerobic exercise 40 minutes three times a week is as effective as topiramate and relaxation training [18]. Biofeedback can also provide long-term benefits for patients with migraine.

Abortive therapy consists of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, with or without caffeine; isometheptene compounds; opioids, with or without aspirin or acetaminophen; barbiturate-containing compounds (e.g., Fiorinal, Fioricet, Esgic, Phrenilin); ergots (e.g., Cafergot, Wigraine, D.H.E. 45); and triptans (sumatriptan, rizatriptan, zolmitriptan, naratriptan, frovatriptan, eletriptan, almotriptan). Keeping headache diaries should be emphasized for better monitoring.

Prophylactic therapy consists of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; topiramate; beta blockers, especially propranolol (except those with sympathomimetic activity); calcium channel antagonists; tricyclic antidepressants, especially amitriptyline; riboflavin (vitamin B2); sodium valproate; and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (weak evidence of benefit). Recently released preventive migraine treatment guidelines from the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society assign sodium valproate, propranolol, metoprolol, and topiramate to the top level of treatment choices on the basis of an assessment of efficacy alone [19].

Cluster

Lifestyle modification includes alcohol avoidance and stress reduction.

Nonpharmacologic therapy employs 100% oxygen; 10 to 12 liters at headache onset by non-rebreather mask for 10 to 15 minutes aborts headache in 80% of patients.

Abortive therapy generally must be parenteral because headaches are short and onset is sudden. Options include oxygen, as previously described; dihydroergotamine, 1 mg subcutaneously; sumatriptan, 6 mg subcutaneously; and parenteral opioids.

Prophylactic therapy includes lithium carbonate, steroids (duration and dose must be limited to avoid side effects; principally used while results are awaited from other prophylactic medications), verapamil (high doses required), sodium valproate (benefit unclear), and topiramate (benefit unclear).

Tension Type

Lifestyle modification includes regular and adequate sleep and aerobic exercise.

Nonpharmacologic therapy includes biofeedback (thermal or electromyographic). Physical therapy focuses on stretching and strengthening exercise rather than on passive modalities.

Acute therapy consists of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and isometheptene combinations. Potentially sedative or habit-forming opioid or barbiturate-containing compounds should generally be avoided.

Prophylactic therapy consists of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, tricyclic antidepressants, and sodium valproate.

Rehabilitation

Patients whose headaches are refractory to currently available treatments suffer significant disability. Secondary depression and medication overuse may develop, along with family dysfunction and poor work performance. The development of chronic pain syndrome (in which patients develop disability out of proportion to the underlying disease, with associated behavioral abnormalities) requires interdisciplinary treatment for best results. The treatment philosophy, which must be accepted by the patient and family, shifts from cure to management. Medication reduction, increased “up” time and regular physical exercise, involvement in hobbies or return to work, and psychological intervention all help return the patient to some semblance of normal living, despite the persistence of headache [20]. Inpatient rehabilitation may be necessary for patients with severe medication overuse, who require special tapering from narcotic or barbiturate drugs, or who have associated medical or psychiatric morbidity that precludes outpatient treatment. Only a handful of such programs exist in the United States because of the reluctance of insurance companies to compensate for them.

Procedures

Onabotulinum toxin type A injections into the pericranial musculature received approval by the Food and Drug Administration for treatment of chronic migraines in 2010. Pooled data from two randomized controlled trials showed that it was useful in patients with chronic migraine (15 or more headache days per month), although its use is limited by cost and insurance coverage problems [21,22]. Episodic or chronic headaches associated with significant pericranial muscle spasm or pain may benefit from localized trigger point injections or occipital nerve blocks [23,24]. Trigger point injections for headache are small-volume injections into one or more tender or painful muscles in the head or neck. The injection may be of a local anesthetic alone, such as 0.5 to 1.5 mL of 0.25% or 0.5% bupivacaine, or in combination with a steroid, such as 1.5 mL of 0.5% bupivacaine and 0.25 mL of methylprednisolone sodium succinate (Solu-Medrol) 20 mg/mL. Trigger point injections may be repeated at 2-month intervals as needed [23]. Greater occipital nerve block is performed by injection of a combination of local anesthetic and steroid 2 cm lateral to the occipital protuberance; a common dose is 2 mL of 2% lidocaine with 5 mg of triamcinolone [24].

Surgery

Ablative surgical procedures on the fifth cranial nerve (radiofrequency, cryotherapy, and alcohol techniques) are employed in cases of refractory cluster headache. Implanted sphenopalatine ganglion stimulators are a promising but investigational approach for some patients. Some women with migraine contemplate oophorectomy, in the belief that elimination of hormonal cycling may eliminate migraine. In fact, abrupt surgical menopause seems to worsen, not improve, migraine, and this procedure should be discouraged. There is no clear evidence on whether closure of patent foramen ovale is helpful in the treatment of migraine with aura. Occipital nerve stimulators are under investigation for treatment of refractory migraine. Other surgical approaches, such as operations to release peripheral “trigger sites,” have scanty evidence of benefit and in the absence of larger trials should not be recommended.

Potential Disease Complications

Inadequately managed headaches can directly or indirectly lead to depression, suicide, addiction and dependence syndromes, unemployment, divorce, and poor progress in school and the workplace. Emerging evidence indicates structural brain changes in some patients with long-duration, poorly controlled migraine attacks [25]. These include iron deposition in areas of the brainstem, white matter lesions, and reduction in gray matter volume. Migraine is a risk factor for ischemic stroke and may also increase the risk of coronary heart disease. Women with migraine are more likely to develop preeclampsia and to suffer postpartum stroke [26].

Potential Treatment Complications

Possible complications from injections include an allergic reaction to the medication and infection. Potential complications from cluster headache surgery include anesthesia dolorosa, dry eye, and facial anesthesia or weakness. Multiple reactions to oral medications are possible, and the clinician should be aware of the side effect profile for any medications prescribed. A 2006 Food and Drug Administration advisory warns about possible serotonin syndrome with concomitant use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors and triptans. From a clinical perspective, the risk appears very low, but it is worth considering in patients using both medications who have unusual side effects. Most experts do not think, however, that the combination is absolutely contraindicated. Overuse of symptomatic medications for headache may lead to medication overuse headache syndromes that can be difficult to treat.