CHAPTER 101

Fibromyalgia

Melissa Colbert, MD; Joanne Borg-Stein, MD

Definition

Fibromyalgia is a syndrome defined by chronic widespread pain of at least 3 months’ duration. It is a multisystem illness associated with neuropsychological symptoms including fatigue, stiffness, unrefreshing sleep, cognitive dysfunction, anxiety, and depression. The majority of patients are women, for whom fibromyalgia is six times more common than in men [1]. The prevalence of the condition increases with age and is greater than 7% in women older than 60 years [2].

A discrete etiology of fibromyalgia has not been identified. Available evidence implicates sensitization of the central and peripheral nervous systems as key in maintaining pain and other core symptoms of fibromyalgia [3–6]. There may be a role for genetics, as individuals with certain genotypes are more likely to develop chronic pain and an overall increased sensitivity to pain during their lifetimes. These genes include catecholamine methyltransferase, sodium and potassium channels, and a number of others. Environmental factors, such as physical or emotional trauma, and infection (e.g., Epstein-Barr virus, Lyme disease, parvovirus), may interact with genetic factors to facilitate the development of fibromyalgia [6].

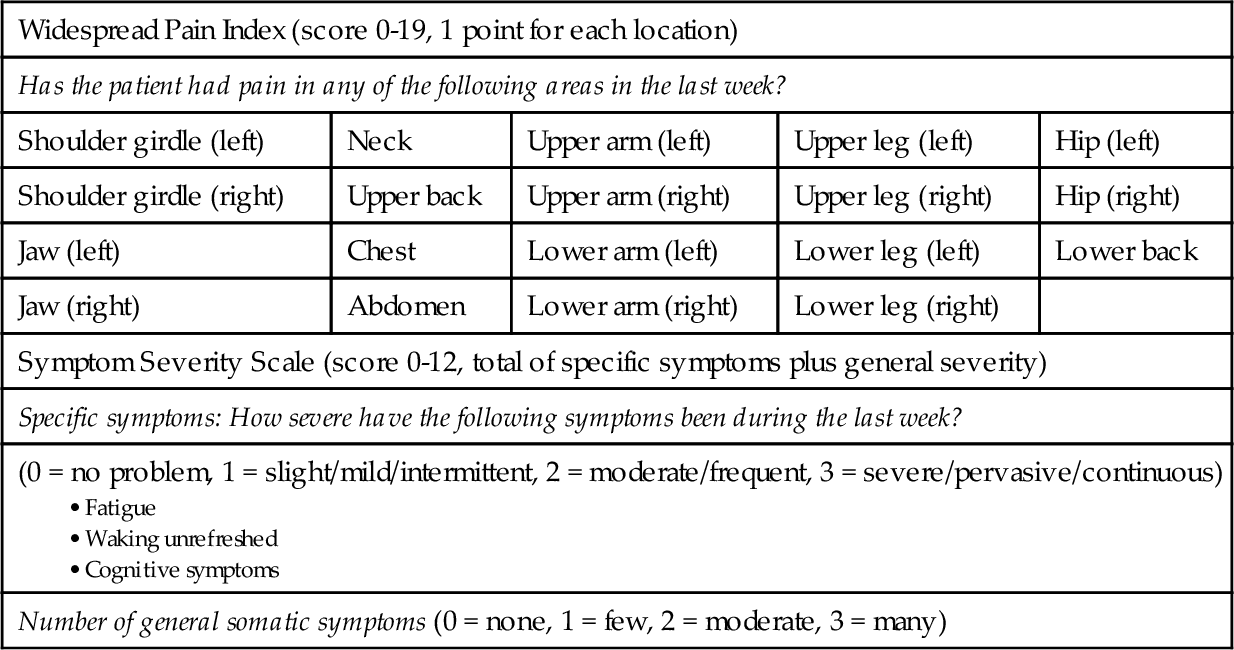

According to the 2010 American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity, a patient must have a widespread pain index score of at least 7 and a symptom severity scale score of at least 5 or a widespread pain index score of at least 3 and a symptom severity scale score of at least 9. The scoring is based on number and severity of somatic symptoms. In addition, symptoms must be present at a similar level for at least 3 months, and the patient must not have another disorder that would otherwise explain the pain (Table 101.1). These criteria do not include a tender point examination, as previously described by the 1990 American College of Rheumatology diagnostic criteria [7].

Data from Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles M, et al. The American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity. Arthritis Care Res 2010;62:600-610.

A patient must have a widespread pain index score of at least 7 and a symptom severity scale score of at least 5 or a widespread pain index score of at least 3 and a symptom severity scale score of at least 9.

Symptoms

Fibromyalgia is characterized by widespread and long-lasting pain (> 3 months) located above and below the waist, on both sides of the body. A series of other symptoms are frequently reported by patients. These include marked fatigue, stiffness, sleep disorders, cognitive disturbances (e.g., decreased comprehension, memory problems), anxiety, depression, temporomandibular joint syndrome, paresthesias, headache, genitourinary manifestations (e.g., pelvic or bladder pain), irritable bowel syndrome, and orthostatic intolerance [4].

Physical Examination

The findings of the general medical examination, including thorough joint inspection, should be normal. Blood pressure recording for orthostatic hypotension is performed. Mood and affect are noted.

The neurologic examination findings should also be largely normal but may demonstrate slight sensory or motor abnormalities [8]. By conducting a comprehensive neurologic and musculoskeletal examination, one may rule out superimposed pain generators, such as bursitis, tendinitis, radiculopathy, and myofascial trigger points.

Functional Limitations

Patients are limited in their daily activities and exercise tolerance by both pain and fatigue. Patients also report cognitive dysfunction with difficulty in concentration, organization, and motivation. This has been termed “fibro fog.” Approximately 25% of patients with fibromyalgia report themselves disabled and are collecting some form of disability payment. Individuals are more likely to become disabled if they report higher pain scores, work at a job that requires heavy physical labor, have poor coping strategies and feel helpless, or are involved in litigation [9–11].

Diagnostic Studies

Fibromyalgia is a clinical diagnosis. For other conditions to be excluded, basic laboratory tests may be appropriate, such as complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, thyroid-stimulating hormone concentration, liver transaminases, and creatine kinase activity. Primary sleep disorders may need to be identified by sleep studies. Radiography or magnetic resonance imaging may be indicated if osteoarthritis, radiculopathy, spinal stenosis, or intrinsic joint disease is suspected.

Electrodiagnostic studies may be useful to rule out an entrapment neuropathy or radiculopathy. The results of these studies will be normal in a patient with fibromyalgia but may be abnormal in the setting of a neuropathy.

Treatment

Initial

Initial treatment includes education of the patient, pharmacologic treatment, gentle exercise, and relaxation training. A stepwise, multidisciplinary approach to fibromyalgia management is recommended. The first step is to confirm the diagnosis, to explain the condition, and to treat any comorbid illness, such as mood or sleep disturbance (see later). Education of the patient, which itself has been shown to have a therapeutic effect, includes individual and group classes that review the symptoms of fibromyalgia and emphasize the importance of adhering to a treatment program. It reassures the patient as to the generally benign course and outlines the treatment path [12–16].

The second step is to use pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic therapy, with emphasis on an individualized treatment plan. Trials with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, or low-dose tricyclic antidepressants should be considered. One may use a combination medication trial or anticonvulsant [15]. The patient should begin a cardiovascular exercise program and be referred for cognitive-behavioral therapy or combine that with exercise.

The third step is specialty referral to rheumatology, physiatry, psychiatry, or pain management.

Pharmacologic management aims to normalize sleep patterns, to reduce fatigue, and to diminish pain. A low-dose tricyclic antidepressant at bedtime (e.g., amitriptyline, 10 to 25 mg) with a low-dose selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (e.g., fluoxetine, 20 mg every morning) is an excellent and cost-effective combination. The combination works better than either medication alone. Cyclobenzaprine, which relies on a mechanism of action similar to that of tricyclic antidepressants, may also be used [17]. Studies demonstrate that the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors duloxetine and milnacipran are beneficial for patients with fibromyalgia, having the greatest impact on important symptoms such as pain and sleep [6,15,18].

Pain may be relieved with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in combination with antidepressants or anticonvulsants, such as gabapentin or pregabalin. Pregabalin reduces pain in patients with fibromyalgia at doses of 300 to 450 mg/day in three divided doses, starting with 50 mg at bedtime and titrating up as tolerated. Opioids are rarely necessary. Tramadol, a μ opiate agonist with serotonergic and noradrenergic effects, may be used alone or in combination with acetaminophen [6,16]. Adjunctive nonpharmacologic pain control methods include acupuncture, massage, aqua therapy, yoga, Thai Chi, and biofeedback [6,19,20].

Rehabilitation

Physical therapy is used to educate the patient in a stretching, gentle strengthening, and cardiovascular fitness program. The aerobic exercise prescription includes low-impact interventions, such as walking and swimming, and should recommend low-intensity exercise that gradually increases to moderate intensity [1]. This can improve fitness and function and decrease pain. Occupational therapy is incorporated to review ergonomics of daily activities, and activities of daily living are reviewed at the work site. Task simplification, pacing, and maximization of function are emphasized [12,21–24].

Mental health professionals can be helpful in the rehabilitative phase to educate the patients in a mind-body stress reduction program, which may include cognitive-behavioral therapy, relaxation, and biofeedback. This provides the patient with positive coping strategies for living with chronic pain [15,25,26]. Associated depression and anxiety often need psychopharmacologic treatment as well.

Procedures

Trigger Point Injections

Myofascial trigger points may be injected with 1% lidocaine to decrease local pain and to increase pain thresholds [27]. Patients with recalcitrant chronic myofascial pain may respond to injections with botulinum toxin [28].

If patients have concurrent bursitis, tendinitis, or nerve entrapment, therapeutic injections may be performed to treat these specific diagnoses.

Acupuncture

Acupuncture can be used for treatment of pain and fatigue. Preliminary studies suggest that the benefit may last up to several months. Treatment two times per week for at least six visits appears necessary. Improvement lasts at least 1 month but is likely to wane over time. The optimal number and frequency of acupuncture treatments have not been determined [2,29–31].

Surgery

There is no surgery indicated for fibromyalgia.

Potential Disease Complications

Failure to make the diagnosis early may lead to delay in treatment, deconditioning, and expensive unnecessary medical testing and procedures. Chronic, intractable pain may occur despite treatment.

Potential Treatment Complications

Tricyclic antidepressant medications can be associated with anticholinergic side effects, such as urinary retention, sedation, constipation, and weight gain. Pregabalin may lead to dizziness, peripheral edema, and weight gain. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor medications may be associated with sexual dysfunction, gastrointestinal intolerance, and anorexia. Overly aggressive exercise programs may transiently increase pain in some patients. Injections may result in local pain, ecchymosis, intravascular injection, or pneumothorax if they are improperly executed. There is an increased risk of bleeding with use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. For patients taking high-dose serotonin reuptake inhibitors, consider avoidance or minimal use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [32]. There is also emerging concern for cardiovascular risks associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [33]. The threshold for seizures is lowered by tramadol. In addition, the risk for seizure is enhanced by the concomitant use of tramadol with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [34].