CHAPTER 100

Costosternal Syndrome

Marta Imamura, MD; David A. Cassius, MD

Definition

Costosternal syndrome is a frequent cause of anterior chest wall pain that affects the costosternal [1–6] or costochondral [2,4–7] joints. The pathogenesis of costosternal syndrome is still unknown [2,8]. Costosternal syndrome is considered an entity distinct from the rarely occurring Tietze syndrome [1–7,9] because it is a frequent cause of benign anterior chest wall pain. Also, as opposed to Tietze syndrome, it is not associated with local swelling of the involved costosternal or costochondral joints [1–7,9], and it usually occurs at multiple sites. The onset is usually after 40 years of age instead of at a young age as in Tietze syndrome, and it affects more women than men. A traumatic cause has been proposed [8], and currently it is suspected that repetitive overuse lesions of the costosternal joint and anterior chest [6,10] may be involved in the development of the degenerative changes found at the costosternal joint [11,12]. The costosternal joints may also be inflamed by osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, Reiter syndrome, psoriatic arthritis, and the SAPHO (synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteitis) syndrome [3,7,12]. Infections of the costosternal joints are associated with tuberculosis, fungus (mycetoma, pulmonary aspergilloma, candidal costochondritis [13]), and syphilis as well as with viruses. The costosternal joints may also be the site of tumor invasion either from a primary malignant neoplasm, such as a chondrosarcoma or thymoma, or from a metastatic carcinoma, most commonly from the breast, kidney, thyroid, bronchus, lung, or prostate [12,14]. Chondromas and multiple exostoses are the most common benign tumors.

Costosternal syndromes may be a primary condition or secondary to these diseases. The condition occurs more frequently in women (a ratio of 2 to 3:1) and at an older age; two thirds of the patients are older than 40 years [1–4, 7,8]. The left side is more often involved. Costosternal joint disease is 1.69 times more frequent in patients who undergo median sternotomy than in normal controls of the same age [15].

Symptoms

The most common symptom in costosternal syndrome is pain of the anterior chest wall, usually localized at the precordium or at the left parasternal region [8,16]. Pain can radiate superiorly toward the left shoulder and left arm [8,16] and also to the neck, scapula, and anterior chest. Pain mainly develops after postural changes and maneuvers that place stress over the chest wall structures [16] rather than with physical efforts, such as those related to pain of cardiac origin [16]. Cardiac etiology for chest wall pain should be considered and ruled out [17]. Cough, deep breathing, and chest and scapular movements usually aggravate pain [5,11]. In contrast to Tietze syndrome, in which only one costal cartilage is involved in the majority of the patients, multiple sites are present in 90% of patients with costosternal syndromes [1,2,7–9]. The second to the fifth costal cartilages are most commonly affected [1–3,5,8,9]. Pain intensity may vary; it usually occurs at rest [12] and lasts for several weeks or months [8,16].

Physical Examination

Inspection of the patient suffering from costosternal syndrome reveals that the patient vigorously attempts to splint the joints by keeping the shoulders stiffly in neutral position [12]. Differing from the Tietze syndrome, the costosternal syndrome has no visible spherical local swelling or any inflammatory signs at the costal cartilages [1,4,5,7,9]. Pain is reproduced by active protraction or retraction of the shoulder, deep inspiration, and elevation of the arm [12]. Palpation of the affected portions of the thoracic cage elicits local tenderness at multiple sites [9]. It may reproduce the patient’s spontaneous pain complaint, including its radiation [9,18,19]. Some authors, however, have not found pain reproduction on palpation [4,5,16–19].

Several maneuvers have been found to be helpful in establishing the diagnosis [8,16]. Application of firm steady pressure to the following chest wall structures elicits the patient’s pain complaint: the sternum, the left and right parasternal junctions, the intercostal spaces, the ribs, the inframammary area, and the pectoralis major and left upper trapezius muscles [8,16,18]. All of these can precipitate pain similar in quality and location to the spontaneous pain [16]. Another maneuver, called the horizontal flexion test (Fig. 100.1), consists of having the arm flexed across the anterior chest with the application of steady prolonged traction in a horizontal direction while, at the same time, the patient’s head is rotated as far as possible toward the ipsilateral shoulder [2,6,8,10,16,18]. Another test, called the crowing rooster maneuver, consists of having the patient extend the neck as much as possible by looking toward the ceiling while the examiner, standing behind the patient, exerts traction on the posteriorly extended arms [2,8,16,18]. Associated myofascial pain syndrome of the intercostal, pectoralis major, pectoralis minor, and sternal muscles is a common feature of the syndrome. These muscles may be tender on palpation. Because this syndrome is usually confused with pain of cardiac [1,2,11,20,21], abdominal [2,9,16,22], or pulmonary [20] origin, a comprehensive history and physical examination are essential in all patients [8,18,19], including athletes [6,10].

Functional Limitations

Functional limitations may be due to the severe incapacitating chest pain [16]. Activities such as lifting, bathing, ironing, combing and brushing hair, and other activities of daily living can be very problematic. Patients will need to be at light duty for weeks and to avoid physical efforts of the upper limbs and trunk [14]. Even after a cardiac origin is ruled out for the chest discomfort, many patients do not return to full employment, recreation, or daily activities [23,24] and remain functionally impaired for years [24]. This functional impairment may occur even in patients with chest pain and normal angiographic studies [23,24] without a proven myocardial infarction. Many of these patients may have a costosternal syndrome. However, the continuing regular physician visits, medication consumption, emergency department visits, repeated hospitalizations, and repeated arteriographies may be contributing to the functional impairment.

Diagnostic Studies

The diagnosis of costosternal syndrome is usually a clinical diagnosis based on the detection of chest wall tenderness [11,16] that reproduces the spontaneous pain on physical examination [8,11,16,18,20,21]. Coronary heart disease [2,4,11,16,20,21], breast conditions [25], and pulmonary conditions [20,21] may be misdiagnosed as costosternal syndrome because of the anatomic proximity of the involved structures. Costosternal syndrome may also coexist with coronary artery disease [2,4,7,11,16,18] and other types of heart diseases [16]. The differentiation from anginal pain due to coronary heart disease may be judged by the pain characteristics. Typical anginal pain is substernal, provoked by exertion, and relieved by rest or nitroglycerin [20]. Atypical anginal pain has two of these symptoms, and nonanginal chest pain has only one of these symptoms [20]. Swap and Nagurney [21] described a low risk for acute coronary syndrome or acute myocardial infarction, with a likelihood ratio of 0.2 to 0.3, when chest pain is described as stabbing, pleuritic, or positional or is reproducible by palpation. The same authors also described a likelihood ratio of 2.3 to 4.7 for acute coronary syndrome when the chest pain radiates to one or both shoulders or arms or is precipitated by exertion [21]. In most patients with costosternal syndromes, the pain is usually localized in the anterior chest or parasternally at the level of the third or fourth intercostal space. As previously mentioned, it can also radiate superiorly toward the left shoulder and down the left arm. Patients experience pain at rest, and the pain can awaken them from sleep [8,16]. Chest pain characteristics, electrocardiographic abnormalities, or cardiac risk factors should be further evaluated by a cardiologist. Radionuclide cineangiographic testing is a sensitive method to differentiate between costosternal syndromes and cardiac diseases [16].

Laboratory and imaging procedures are helpful in the diagnosis of the possible secondary causes of the costosternal syndromes and to rule out other causes of anterior chest pain [11,14].

Plain radiographs are indicated for patients who present with pain possibly emanating from the costosternal joints to rule out occult bone tumors, infections, and congenital defects. If trauma has occurred, costosternal syndrome may coexist with occult rib fractures or fractures of the sternum. These fractures may be missed on plain radiographs and can require radionuclide bone scanning for proper diagnosis. Increased uptake of radioactivity on bone scans is seen in most patients; however, it is not a specific test for making the diagnosis of costosternal syndrome [26].

Additional testing, including complete blood count, prostate-specific antigen level, sedimentation rate, and antinuclear antibody titer, may be indicated to rule out other diseases that may cause a costosternal syndrome, such as rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, Reiter syndrome, and psoriatic arthritis. Magnetic resonance imaging of the joints is indicated if joint instability or occult mass is suspected. Diagnostic ultrasonography may also be indicated to investigate the presence of an occult mass.

Neuropathic pain caused by diabetic polyneuropathies and acute herpes zoster involving the chest wall may also be confused or coexist with costosternal syndrome [12].

A highly reliable test (and an effective differential diagnostic procedure that can confirm the diagnosis of costosternal syndrome) is the complete pain relief noted after an intercostal block at the posterior axillary line [8]. Patients with cardiac disease will have little or no effect on their pain because the nociceptive pathways from the heart are in the sympathetic afferents located in the paravertebral region. This test is both diagnostic and therapeutic.

In the secondary forms of costosternal syndromes, the underlying conditions should be addressed for good results [16].

Treatment

Initial

Initial treatment of the pain and functional disability associated with costosternal syndromes should include simple oral analgesics [2,18], such as acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [12,27], alone or in combination with codeine [8] or tramadol. The use of an elastic rib belt may also provide symptomatic relief and help protect the costosternal joints from additional trauma [12]. Reassurance that the diagnosis is a non–life-threatening musculoskeletal pain syndrome can often by itself reduce the anxiety and fears and lead to symptomatic pain relief [2,6–9,11,16,27].

Rehabilitation

Physical modalities, such as local superficial heat for 20 minutes, two or three times a day, or ice for 10 to 15 minutes, three or four times a day, can be performed while symptoms are present [11,18]. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation and electroacupuncture may be applied over the painful area. Gentle, pain-free range of motion exercises should be introduced as soon as tolerated. There is limited evidence to suggest that stretching exercises help for costochondritis pain [28]. Vigorous exercises should be avoided because they exacerbate the patient’s symptoms. Perpetuating and aggravating factors [27], such as chronic coughing and bronchospasm, among others, should always be removed.

Procedures

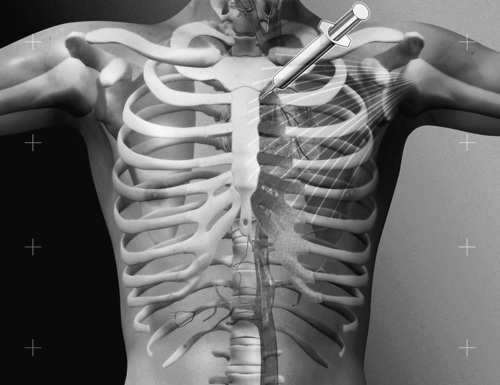

For patients who do not respond to the initial or rehabilitation treatment modalities, a local anesthetic and steroid injection [5,6,9,11,12,25] can be performed as the next symptom control maneuver. Even in patients with coexisting true anginal pain, the relief of local chest pain is evident. Intra-articular injection of the costosternal joint (Fig. 100.2) is performed with the patient in the supine position [12]. The area of maximum tenderness can be infiltrated with a local anesthetic (2% lidocaine [7,25] or 0.25% preservative-free bupivacaine [12]) and methylprednisolone acetate [7,11,12,25] at the dosage of 10 mg per costosternal joint [25] by use of a 11⁄2-inch, 25-gauge needle with strict aseptic technique [12]. The costosternal joints should be easily palpable as a slight bulging at the point where the rib attaches to the sternum [12]. An intercostal block at the posterior axillary line provides complete relief for 6 to 10 hours [8].

Surgery

Surgical procedures are rarely necessary [9]. Costosternal or sternoclavicular arthrodesis may be performed if conservative measures fail to provide satisfactory results.

Potential Disease Complications

Costosternal syndromes are of benign origin, and complications rarely develop. They are self-limited [9], and spontaneous recovery usually occurs after 1 year in the majority of the cases [4]. Pain exacerbation due to physical activities and overload is usually followed by spontaneous recovery. However, as mentioned earlier, because of the many pathologic processes that may mimic the pain of costosternal syndrome, the clinician should always be careful to rule out underlying cardiac, lung, breast, and mediastinum diseases.

Potential Treatment Complications

The systemic complications of analgesics such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are well known and most commonly affect the gastric, hepatic, and renal systems. Local steroid combined with local anesthetic injections may cause pneumothorax if the needle is placed too laterally or deeply and invades the pleural space [12]. Cardiac tamponade as well as trauma to the contents of the mediastinum, although rare, can occur. This complication can be greatly decreased if the clinician pays close attention to accurate needle placement [12] or performs the injection with ultrasonographic guidance. Transient marked hypophosphatemia has been documented 8 hours after an intra-articular glucocorticoid injection in a patient with chronic costochondritis [29]. In this patient, hypophosphatemia was clinically characterized by limb paresthesia and weakness, followed by dysarthria [29]. All of these symptoms resolved within hours, even before the hypophosphatemia resolved [29]. Iatrogenic infections can also occur if strict aseptic techniques are not followed [12].