CHAPTER 10 Volatile Anesthetics

2 What are the chemical structures of the more common anesthetic gases? Why do we no longer use the older ones?

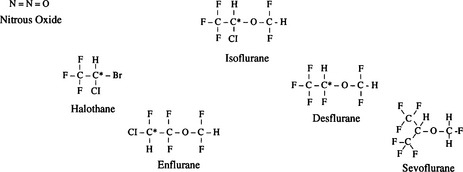

Isoflurane, desflurane, and sevoflurane are the most commonly used volatile anesthetics. As the accompanying molecular structures demonstrate, they are substituted halogenated ethers, except halothane, a halogenated substituted alkane. Many older anesthetic agents had unfortunate properties and side effects such as flammability (cyclopropane and fluroxene), slow induction (methoxyflurane), hepatotoxicity (chloroform and fluroxene), nephrotoxicity (methoxyflurane), and the theoretic risk of seizures (enflurane) (Figure 10-1).

5 Define partition coefficient. Which partition coefficients are important?

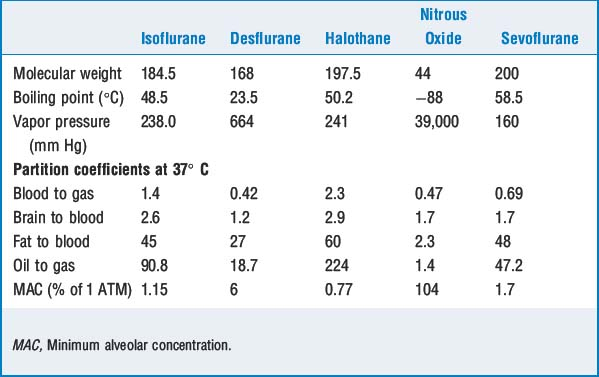

Other important partition coefficients include brain to blood, fat to blood, liver to blood, and muscle to blood. Except for fat to blood, these coefficients are close to 1 (equally distributed). Fat has partition coefficients for different volatile agents of 30 to 60 (i.e., anesthetics continue to be taken into fat for quite some time after equilibration with other tissues) (Table 10-1).

6 Review the evolution in hypothesis as to how volatile anesthetics work

At the turn of the century Meyer and Overton independently observed that an increasing oil-to-gas partition coefficient correlated with anesthetic potency. The Meyer-Overton lipid solubility theory dominated for nearly half a century before it was modified.

At the turn of the century Meyer and Overton independently observed that an increasing oil-to-gas partition coefficient correlated with anesthetic potency. The Meyer-Overton lipid solubility theory dominated for nearly half a century before it was modified. Franks and Lieb found that an amphophilic solvent (octanol) correlated better with potency than lipophilicity and concluded that the anesthetic site must contain both polar and nonpolar sites.

Franks and Lieb found that an amphophilic solvent (octanol) correlated better with potency than lipophilicity and concluded that the anesthetic site must contain both polar and nonpolar sites. Modifications of Meyer and Overton’s membrane expansion theories include the excessive volume theory, in which anesthesia is created when a polar cell membrane components and amphophilic anesthetics synergistically create a larger cell volume than the sum of the two volumes together.

Modifications of Meyer and Overton’s membrane expansion theories include the excessive volume theory, in which anesthesia is created when a polar cell membrane components and amphophilic anesthetics synergistically create a larger cell volume than the sum of the two volumes together. In the critical volume hypothesis, anesthesia results when the cell volume at the anesthetic site reaches a critical size. These theories rely on the effects of membrane expansion on and at ion channels.

In the critical volume hypothesis, anesthesia results when the cell volume at the anesthetic site reaches a critical size. These theories rely on the effects of membrane expansion on and at ion channels. The previous theories oversimplify the mechanism of anesthetic action and have been abandoned for the following reasons: volatile anesthetics lead to only mild perturbations in lipids, and the same changes can be reproduced by changes in temperature without leading to behavioral changes; also, variations in size, rigidity, and location of the anesthetic in the lipid bilayer are similar to those in compounds that do not have anesthetic activity, which implies that specific receptors are involved.

The previous theories oversimplify the mechanism of anesthetic action and have been abandoned for the following reasons: volatile anesthetics lead to only mild perturbations in lipids, and the same changes can be reproduced by changes in temperature without leading to behavioral changes; also, variations in size, rigidity, and location of the anesthetic in the lipid bilayer are similar to those in compounds that do not have anesthetic activity, which implies that specific receptors are involved. Newer accepted theories propose distinct molecular targets and anatomic sites of action rather than nonspecific actions on cell volume or wall. Volatile anesthetics are thought to enhance inhibitory receptors, including γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) type A and glycine receptors.

Newer accepted theories propose distinct molecular targets and anatomic sites of action rather than nonspecific actions on cell volume or wall. Volatile anesthetics are thought to enhance inhibitory receptors, including γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) type A and glycine receptors. There is also evidence supporting an inhibitory effect on excitatory channels such as neuronal nicotinic and glutamate receptors.

There is also evidence supporting an inhibitory effect on excitatory channels such as neuronal nicotinic and glutamate receptors. Most likely the actions of immobilization and amnesia are caused by separate mechanisms at different anatomic sites. At the spinal cord level anesthetics lead to suppression of nociceptive motor responses and are responsible for immobilization of skeletal muscle. Supraspinal effects on the brain are responsible for amnesia and hypnosis. The thalamus and midbrain reticular formation are more depressed than other regions of the brain.

Most likely the actions of immobilization and amnesia are caused by separate mechanisms at different anatomic sites. At the spinal cord level anesthetics lead to suppression of nociceptive motor responses and are responsible for immobilization of skeletal muscle. Supraspinal effects on the brain are responsible for amnesia and hypnosis. The thalamus and midbrain reticular formation are more depressed than other regions of the brain.7 What factors influence speed of induction?

Factors that increase alveolar anesthetic concentration speed onset of volatile induction:

Factors that decrease alveolar concentration slow onset of volatile induction:

8 What is the second gas effect? Explain diffusion hypoxia

KEY POINTS: Volatile Anesthetics

9 Should nitrous oxide be administered to patients with pneumothorax? Are there other conditions in which nitrous oxide should be avoided?

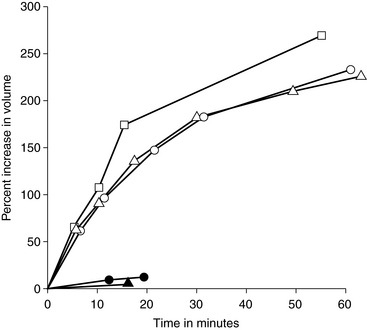

Although nitrous oxide has a low blood-to-gas partition coefficient, it is 20 times more soluble than nitrogen (which comprises 79% of atmospheric gases). Thus nitrous oxide can diffuse 20 times faster into closed spaces than it can be removed, resulting in expansion of pneumothorax, bowel gas, or air embolism or in an increase in pressure within noncompliant cavities such as the cranium or middle ear (Figure 10-2).

11 What effects do volatile anesthetics have on hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction, airway caliber, and mucociliary function?

16 Which anesthetic agent has been shown to be teratogenic in animals? Is nitrous oxide toxic to humans?

1. Campagna J.A., Miller K.E., Forman S.A. Mechanisms of actions of inhaled anesthetics. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2110-2124.

2. Coppens M.J., Versichelen L.F.M., Rolly G., et al. The mechanism of carbon monoxide production by inhalational agents. Anaesthesia. 2006;61:462-468.

3. Eger E.I.II, Saidman L.J. Hazards of nitrous oxide anesthesia in bowel obstruction and pneumothorax. Anesthesiology. 1965;26:61-68.

4. Myles P.S., Leslie K., Chan M.T.V., et al. Avoidance of nitrous oxide for patients undergoing major surgery. Anesthesiology. 2007;107:221-231.

5. Sanders R.D., Weimann J., Maze M. Biologic effects of nitrous oxide. Anesthesiology. 2008;109:707-722.