This chapter reviews the background to recent policy developments in relation to the registration of Chinese medicine, naturopathy and western herbal medicine (WHM) and discusses what factors have shaped policy development, and might shape future policy. In doing so, the chapter illustrates that health policy is often not a single decision but a series of actions that affect a set of institutions, services, and the community. Policy development then reflects the continued engagement of a range of actors in a process of policy debate, who represent different interests, and who respond to changing social, economic, and political contexts.

COMPLEMENTARY AND ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE DEFINED

The umbrella term CAM encompasses a large array of health practices and occupations generally considered alternative or complementary to the mainstream health system. The term CAM can be problematic, as it groups together divergent practices, but has been adopted as a policy terminology of convenience. The nature of CAM practices and its increasing adoption by biomedical practitioners (known as integrative medicine) means the boundary between CAM and biomedicine is not always sharply defined or fixed. While Table 10.1 lists some of the major CAM systems in Australia, our focus on Chinese medicine (including acupuncture), naturopathy and WHM means this chapter relates to a limited, albeit significant, number of CAM practices.

|

Table 10.1 Categories and examples of common CAM modalities |

|

| CAM Classification | CAM modalities |

|---|---|

| Alternative medical systems | Acupuncture Homoeopathy Naturopathy Ayurveda |

| Mind–body interventions | Meditation Yoga Biofeedback |

| Biologically based therapies | Aromatherapy Herbal medicine – Chinese and Western Clinical nutrition, including Chinese medicine dietary medicine, multivitamins and minerals |

| Manipulative and body-based methods | Therapeutic massage, including Shiatsu Chiropractic Osteopathy Reflexology |

| Energy therapies | Energy healing (e.g. Reiki and therapeutic touch) Qi gong, Martial arts and Tai Chi |

|

Source: Adapted from National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) 2006; Xue et al. 2006 |

|

In terms of the three practices of concern to this chapter:

1. Naturopathy is reported to be the second most frequented CAM practice, after chiropractic (MacLennan et al. 2006). Naturopaths utilise a variety of therapies and diagnostic tools (Bensoussan et al. 2004), with herbal medicine, nutrition, homoeopathy and tactile therapies (e.g. massage) the four main therapeutic modalities.

2. Western herbal medicine has a long history of traditional use, is the fourth most frequented CAM practice (MacLennan et al. 2006), and is associated with a large empirical knowledge base (Myers 2006). There is a significant overlap between naturopathy and WHM in that many naturopaths practise WHM and some trained naturopaths choose to specialise in WHM and identify as WHM practitioners. Alongside this, WHM can be viewed as a distinct profession with history, education and institutions separate from naturopathy.

3. Chinese medicine, also known as traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), was introduced to Australia in the 1850s and is based on strong theoretical foundations as well as a substantial volume of historical records dating back a few thousand years. TCM is a system of healthcare that includes acupuncture, herbal medicine, remedial massage, diet, and lifestyle advice. Like naturopathy and WHM, TCM also draws from a paradigm or knowledge base different from biomedicine. Acupuncture is the third most frequented CAM practice in Australia (MacLennan et al. 2006).

With underlying philosophies and principles quite different from those underlying biomedicine, the differences among CAM professions, in worldviews, in the diversity of practices, and the practitioners’ desire for autonomy of their particular CAM domain, increasing the challenge of regulating CAM professions (Canaway 2007).

AUSTRALIAN POLICY FRAMEWORK FOR HEALTH WORKFORCE REGULATION

The circumstance where Chinese medicine is a registered profession only in Victoria is possible due to the division of regulatory jurisdiction in Australia. While regulation of therapeutic products, including CAM medicaments, is overseen by the federal government through the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA), workforce regulation is under state and territory jurisdiction, and so need not be uniform across the country.

The difference in level of regulation of the same profession generally reflects historical and institutional arrangements, rather than objective assessments of risk to public health and safety (Australian government 2006b). Concerns about the level of regulatory differences across Australia and the impact this has on enterprise and competition, in all areas, not just health, led to the Commonwealth Mutual Recognition Act 1992, relating to the free movement of goods and services (Australian government 2000).

Further, in 1995 the National Competition Policy (NCP) committed all governments to review legislation and remove unnecessary regulation which might impede competition. Around the same time, the Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council (AHMAC) established criteria for assessing the regulatory requirements for unregulated health professions. All six criteria must be satisfactorily met for the consideration of statutory registration. These criteria are:

3. Do existing regulatory or other mechanisms fail to address health and safety issues?

4. Is regulation possible to implement for the occupation in question?

5. Is regulation practical to implement for the occupation in question?

6. Do the benefits to the public clearly outweigh the potential negative impact?

Thus, the national policy context for health workforce regulation, including CAM professions, has been framed since the 1990s by:

In 2006, the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) adopted the recommendation of the Productivity Commission’s health workforce report for a national approach to the registration and course approval of health professions. This further signifies the trend towards nationally defined standards and a common regulatory approach to all health professions (see also Chs 3, 4 & 9).

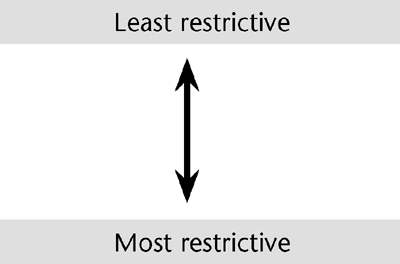

Table 10.2 lists the main regulatory models for all health professions. Self-regulation of CAM is currently the norm in every state and territory. The Victorian Chinese Medicine Registration Act 2000, legislating for reservation of title, is the only statutory regulation of a CAM profession in Australia, excluding chiropractic and osteopathy. Reservation of title is the most common approach used for regulation of health professions and in the case of Chinese medicine in Victoria, outlaws the use of such titles as acupuncturist, Chinese medicine practitioner, Chinese herbal practitioner, Chinese herbal dispenser, and so on, by anyone other than a registered practitioner. This model of regulation does not prohibit other people from offering similar practices, but does make it an offence to do so and use these titles. The July 2007 adoption of the Health Professions Registration Act 2005 in Victoria repealed all profession-specific registration Acts and further reinforced the common approach adopted for health workforce regulation.

|

Table 10.2 General models for regulation of health professions |

|

|

|

A LONGSTANDING PROBLEM: THE HISTORICAL BACKGROUND TO POLICY DEVELOPMENTS FOR CAM

Throughout the 20th century in Australia, the impetus for professional registration had come from within the ranks of CAM practitioners (see Table 10.3). In the 1920s, the threat of ‘anti-quackery’ laws with the potential to outlaw or limit practice motivated herbalists and chiropractors to seek registration as a means of gaining greater institutional and professional recognition (Bentley 2005, Martyr 2002). Public support and arguments for freedom of choice and the benefits of competition, quelled the early legislative threats to herbalists and other ‘irregular’ medical practitioners (Bentley 2005, Martyr 2002).

|

Table 10.3 Chronology of key 20th century policy developments to the 1990s |

||

| Year | Institution, jurisdiction | Development |

|---|---|---|

| May 1924 | Victoria | Western and Chinese herbalists mount successful campaign to defeat proposed amendment to the Medical Act that would restrict herbalists’ access to herbal medicines (Bentley 2005). |

| 1925 | Victoria | Moves to introduce anti-quackery law to restrict medical practice to registered practitioners (Martyr 2002). |

| 1961 | Western Australia | Report of the Honorary Royal Commission appointed to inquire into the provisions of the Natural Therapists Bill (Guthrie 1961). Report encouraged prohibition of naturopaths, and led to Chiropractors Registration Act 1964 in Western Australia. |

| 1974 | Federal NHMRC | Acupuncture: A Report to the National Health and Medical Research Council (McLeod et al. 1974).1 |

| November 1975 | Victoria | Report from the Osteopathy, Chiropractic and Naturopathy Committee (Victorian Parliament Joint Select Committee 1975). |

| April 1977 | Federal | Report of the Committee on Inquiry into Chiropractic, Osteopathy, Homoeopathy, and Naturopathy (Webb 1977). Deemed naturopathy a ‘minor cult system’ and led to registration for chiropractors and osteopaths in jurisdictions other than Western Australia. |

| 1981 | Victoria | Report to the Health Commission of Victoria on the Registration of Acupuncturists by the Health Advisory Council. |

| August 1985 | Northern Territory | Registration of ANTA natural therapists in Northern Territory. Registration revoked following Mutual Recognition Act. |

| December 1986 | Victorian Parliament | Inquiry into Alternative Medicine and the Health Food Industry (SDC 1986a, 1986b). |

| November 1989 | NHMRC | Working Party Report on the Practice of Acupuncture, National Health & Medical Research Council (NHMRC Acupuncture Working Party 1989). |

While inquires in the 1960s and 1970s led to practitioner registration for chiropractors and osteopaths, the same was not recommended for naturopathy or other natural therapies (Table 10.3). The 1986 Victorian Parliamentary inquiry was the first to acknowledge that ‘alternative medicine practitioners represent primary contact healthcare providers for a significant proportion of the Victorian public’ (Social Development Committee [SDC] 1986a p 179). Once again, however, registration was not recommended, on the grounds that naturopaths presented little concern for causing public harm, and because registration would imply government endorsement of the body of knowledge that supported alternative medicine (SDC 1986a p 181).

Changing ideologies have impacted on policy development relating to CAM. By the 1980s, banning or restricting medical practices, even when their knowledge was based on philosophy and practices divergent from orthodox medicine, had come to be regarded as an unacceptable ‘relic of medical paternalism’ (National Health and Medical Research Council [NHMRC] 1989 p 76). Perhaps of greater impact in bringing CAM to the attention of government, the medical profession and policy makers, has been the increasing usage of CAM that has led to it becoming a multi-billion dollar industry, through increased use of CAM products as well as adopting of CAM practices (MacLennan et al. 2006).

Reasons for consumers seeking care by CAM practitioners include finding that conventional healthcare has not relieved symptoms, preferring longer and more supportive consultations, wanting lifestyle counselling alongside illness treatment, or generally seeking holistic or proactive approaches to healthcare (Lin et al. 2006). CAM practitioners are sought for treatment of a wide range of complaints including the alleviation of side effects from orthodox medicine, and particularly for help with chronic conditions (Lin et al. 2006). For many consumers, negotiating across parallel primary care systems of the GP and the CAM practitioner has become the norm.

Changes in the attitude of medical professionals towards CAM also have a bearing on shifting attitudes that might ultimately inform policy relating to CAM. Changes in attitude from medical professionals reflect not only responsiveness to consumer demands but also increasing reports of the effectiveness of CAM practices. Some GPs now refer patients to CAM therapies (Pirotta et al. 2000), some report that they use CAM themselves, or offer CAM therapies to patients (Leach 2004, Lin et al. 2006, Wilkinson & Simpson 2002). Some clinicians trained in conventional healthcare (e.g. nurses, physiotherapists or pharmacists) take a further step by training to become a CAM practitioner. Medical practitioners have sufficiently embraced acupuncture for it to now have a presence within the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) and gain Medicare rebates for these services, which is something denied non-medical establishment acupuncturists.

RECENT POLICY RESPONSES

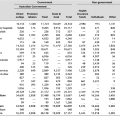

The policy developments in the last decade, as outlined in Table 10.4, occurred against this background of increasing consumer usage and interest from medical practitioners.

|

Table 10.4 Chronology of key policy developments, 1990s to 2006 |

||

| Year | Institution – jurisdiction | Development |

|---|---|---|

| April 1995 | Victorian Government DHS | Review of Traditional Chinese Medicine commenced. |

| November 1996 | Victorian Government DHS | Towards a Safer Choice: The Practice of Chinese Medicine in Australia (Bensoussan & Myers 1996). |

| September 1997 | Victorian Government DHS | Review of Traditional Chinese Medicine – Discussion Paper (Victorian Ministerial Advisory Committee 1997). |

| December 1997 | Australian government | The Complementary Medicines Evaluation Committee (CMEC) established to advise the TGA. |

| July 1998 | NSW Parliament | Unregistered Health Practitioners: The adequacy and appropriateness of current mechanisms for resolving complaints – Discussion Paper (Committee on the Health Care Complaints Commission [CHCCC] 1998) (see also September 2006). |

| July 1998 | Victoria | Final report by the Victorian Ministerial Committee: Chinese Medicine – Report on Options for Regulation of Practitioners (Victorian Ministerial Advisory Committee 1998). |

| April 1999 | Federal Parliament | GST legislation passed through Senate with naturopathy, western and Chinese herbal medicines and acupuncture included as GST-free services (Australian Taxation Office 2006). |

| 1999 | Australian government | Establishment of the Complementary Healthcare Consultative Forum (CHCF) by Senator Grant Tambling to assist in communication between government, the complementary healthcare industry, and consumers. |

| May 2000 | Victorian Parliament | Chinese Medicine Registration Act 2000. Chinese Medicine Registration Board established in December 2000. |

| February 2002 | AMA | Release of Position Statement on complementary medicine (AMA 2002). |

| September 2002 | NSW Department of Health | Regulation of Complementary Health Practitioners – Discussion Paper (NSW Health 2002b) |

| October 2002 | Victorian Government DHS | DHS initiates review of health practitioner regulation in Victoria – includes a study of naturopathy and Western herbal medicine. |

| November 2002 | NSW Health | NSW Health Minister Craig Knowles announces ‘crackdown on “miracle cures”, “wonder drugs” and misleading health claims and advertisements to protect people who are sick and vulnerable’ including the establishment the NSW Health Care Complaints and Consumer Protection Advisory Committee, chaired by Professor John Dwyer (NSW Health 2002a). Committee later became informally known as the ‘Quackwatch’ Committee. |

| April 2003 | Australian government TGA | TGA suspends Pan Pharmaceuticals’ manufacturing licence. Product recall increases to over 1600 items, the majority being complementary medicines. Leads to Expert Committee review (see September 2003). |

| July 2003 | Australian government | Only ‘recognised’ naturopathic, herbal and acupuncture/Chinese medicine practitioners eligible to provide GST-free services after June 2003. |

| September 2003 | Australian government | Complementary Medicines in the Australian Health System – Report to the Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister for Health and Ageing (Expert Committee 2003). |

| June 2005 | NSW Parliament | Parliamentary Inquiry – Possible Regulation or Registration of the Practice of Traditional Chinese Medicine (see also November 2005). |

| July 2005 | WA Department of Health | Regulation of practitioners of Chinese Medicine in Western Australia (WA DOH 2005). |

| November 2005 | NSW Parliament | Report into Traditional Chinese Medicine (CHCCC 2005). |

| August 2006 | Victorian Government DHS | The practice and regulatory requirements of naturopathy and western herbal medicine (Lin et al. 2006) Commissioned in 2003 as part of a review of regulation of the health professions. |

| September 2006 | NSW Parliament | Review of the 1998 Report into ‘Unregistered Health Practitioners: The Adequacy and Appropriateness of Current Mechanisms for Resolving Complaints’, Final Report (HCCC 2006). |

| December 2006 | NSW Parliament | Introduction of system of negative licensing for unregistered health professions in NSW through assent of Health Legislation Amendment (Unregistered Health Practitioners) Bill 2006 (Legislative Assembly 2006). |

| July 2007 | Victoria | The Health Profession Registration Act 2005 comes into operation, repealing the 11 separate health practitioner Acts previously in operation in Victoria–including the Chinese Medicine Registration Act 2000. The 11 existing health practitioner registration boards continue under the legislation (DHS 2007). |

Victorian review of Chinese medicine

In 1995, following extensive lobbying by Chinese medicine practitioners, the Victorian DHS instigated a review of Chinese medicine practice, jointly funded by the governments of New South Wales, Victoria and Queensland (Carlton 2005). Anne-Louise Carlton, senior policy analyst, oversaw the review along with a steering committee of stakeholders. Carlton became the champion of the project, committed to seeing the collaborative task through, even when it threatened to fold during times of change of minister or government (Bennett 2002).

Importantly, the policy research by Bensoussan and Myers (1996) found that the practice of Chinese medicine posed risks to public health safety, in part related to the toxic nature of some of the herbs, the absence of agreed educational standards and the wide variation in the types of courses being offered, and the proliferation of competing professional associations. The report suggested that in the absence of an industry able to self-regulate, government intervention was called for, as all six criteria set by AHMAC for occupational registration had been met.

A ministerial advisory committee was subsequently established, comprising leaders in both Chinese and western medicine, to consider the recommendations arising from the policy research and to undertake broadly based community consultation. Its report was launched by the then Premier, Jeff Kennett. The Chinese Medicine Registration Act was initially introduced into the Victorian Parliament by a Coalition government in 1999 and reintroduced by a Labor government, following a state election, and passed with bipartisan support in 2000. Some medical professional bodies lobbied strongly in an attempt to prevent passage of the Bill. In response, amendments were made to remove requirements for the Medical Board (and some other boards) to consult with the Chinese Medicine Registration Board (CMRB) before endorsing their registrants to practice Chinese medicine.

The CMRB was established later that year – its main functions to register Chinese medicine practitioners, accredit courses, and regulate standards of practice (Lin & Gillick 2006). The initial board comprised practitioners who had been either on the steering committee for the earlier policy research, or members of the subsequent ministerial advisory committee. Some of these practitioners had also been involved in lobbying throughout the 1980s and 1990s, for different professional associations. About 10% of the registrants since the inception of the CMRB have been from other Australian states, particularly New South Wales, Queensland and Western Australia. It appears that some CAM practitioners consider registration to confer higher professional competence or status (Bensoussan et al. 2004), which might account for the interstate registrants. At the same time, there has been misunderstanding about registration being substitutable by professional association membership (Lin & Gillick 2006).

Review of naturopathy and western herbal medicine

In October 2002, Carlton became responsible for a system-wide review of the regulation of health professions in Victoria. As a part of this review, a study of the risks, benefits and regulatory requirements for the profession of naturopathy and WHM was commissioned. The resulting report, completed in early 2005 but not released until August 2006, recommended statutory regulation of naturopaths and WHM practitioners (Lin et al. 2006). This recommendation was based on findings which were similar to the earlier study by Bensoussan and Myers (1996) in relation to Chinese medicine, including the increased reporting of adverse events and coroner’s cases related to CAM use. It was also based on the potential for risk from concurrent use of CAM products and conventional medicines, particularly given the limited data on drug–herb and drug–nutrient interactions; and the inability of the industry to agree on and enforce minimum educational and practice standards.

National positioning relating to complementary and alternative medicine

Statutory regulation, however, is not always what governments adopt as a policy position. In November 2002, the then New South Wales Health Minister, Craig Knowles, announced a crackdown on ‘wonder drugs’ and ‘miracle cures’. The crackdown, to ‘combat dodgy cures and health practices’, among other things, promised to ‘strengthen the powers to investigate and prosecute quacks’ (NSW Health 2002a). To help do this, an Expert Committee was established, the New South Wales Healthcare Complaints and Consumer Protection Advisory Committee (HCCPAC), chaired by Professor John Dwyer, a known critic of CAM. The committee became informally known as the ‘Quackwatch’ Committee.

In April 2003, the TGA suspended Pan Pharmaceuticals’ manufacturing licence after adverse reactions to an over-the-counter travel sickness pharmaceutical prompted investigation which uncovered poor manufacturing standards including large variation in active ingredients, contamination and ingredient substitution. Pan Pharmaceuticals was a major manufacturer of complementary medicines, and over the ensuing weeks more than 1600 products (the majority CAM) were recalled from the market – the largest ever product recall in Australia. Despite the massive recall, no CAM product manufactured by Pan was found to have caused adverse reactions, but this event raised awareness of complementary medicines and provided opportunity for a media-led storm of criticism and warnings about the dangers of CAM. This event instigated the formation of an Expert Committee to review complementary medicines in the health system (Expert Committee 2003).

Although the focus of the federal government is on regulation of CAM products, the report by the Expert Committee on Complementary Medicines in the Health System made recommendations relating to practitioners as well. They urged all states and territories to ‘move more quickly to nationally consistent, statutory regulation (where appropriate) of complementary healthcare professions’ (Expert Committee 2003 p 23). In particular, the committee saw the Victorian Chinese medicine legislation as an appropriate framework for the national regulation of Chinese medicine practitioners and dispensers, and saw the need for: ‘effective, transparent and accountable self-regulatory structures for complementary healthcare practitioners’. These included: a) certification system; b) code of ethics; c) effective procedures for receiving, investigating and resolving consumer complaints; d) an established disciplinary system for enforcing conduct and continuing professional development (Expert Committee 2003 p 31).

In relation to the Expert Committee recommendations, the Australian government referred the matter to the Australian Health Workforce Officials’ Committee (an AHMAC sub-committee). This committee then established a regulation sub-committee to examine, among other things, mechanisms for nationally consistent regulation of TCM practitioners (Australian government 2006a).

In 2004, the NSW Minister for Health established a ministerial advisory committee to consider options for regulation of CAM practitioners, with Chinese medicine being of initial concern. By June 2005, the New South Wales Parliament also established an inquiry to report on regulation or registration for TCM. This inquiry recommended that TCM be registered in New South Wales through protection of title (CHCCC 2005). In December 2006 a Bill was assented to, to amend existing health legislation to bring all registered and unregistered health practitioners, including CAM practitioners, under the control of the Health Care Complaints Commission (HCCC) (Legislative Assembly 2006). In effect this Act implements ‘negative licensing’ whereby health practitioners deregistered by a board cannot adopt the titles of unregistered professions, and the HCCC can prohibit unregistered health practitioners found to pose a substantial risk to the public from practising. Since the Parliament of New South Wales has taken this approach, it appears that legislation to register the Chinese medicine profession in New South Wales has slowed.

In June 2005, the Western Australia Department of Health (WA DOH) released a discussion paper canvassing stakeholder views on appropriate regulatory models for practitioners of Chinese medicine (WA DOH 2005). One of the options for registration was for Western Australia to ‘contract’ with Victoria for registration, in light of the small number of practitioners in Western Australia.

National approach to health workforce regulation

Early in 2006, the Productivity Commission’s Health Workforce Report was released, highlighting problems with health workforce shortages and increasing demand for services (Productivity Commission 2005). In July 2006, COAG accepted the recommendation to adopt uniform national standards for practitioner registration through a single national registration board and a single authority for course approvals. The inclusion of health occupations registered in limited jurisdictions, and subsequent inclusion of new professions, will be determined during implementation of the scheme (COAG 2006). Given Chinese medicine registration is operating only in Victoria, it is one of the ‘partially registered’ professions left out of the COAG agreement. Despite the subsequent Victorian DHS offer to other jurisdictions to host discussions about a national approach to Chinese medicine registration, the policy focus on other professions has kept Chinese medicine, along with the issue of other CAM professions (including the Lin et al. report on naturopathy and WHM released by DHS in mid-2006) on the periphery.

POLICY ANALYSIS

The unfolding of the story of CAM practitioner registration can be understood through analysis of the contexts and processes within which policy actors interact, as suggested by Walt and Gilson (1994) in the health policy triangle framework. For much of the 20th century, the only proponents of registration have been CAM practitioners, against a backdrop of medical dominance in the Australian health system and over health policy.

Although CAM practitioners have long lobbied for regulation, they have not been united in their drive for statutory registration. The lack of unity reflects in part on different philosophical and practice traditions, and in part on interests of different professional associations and educational institutions (Canaway 2007). For example, dozens of professional associations exist which represent the interests of CAM practitioners (Bensoussan et al. 2004; Lin et al. 2006), and practitioners hold multiple memberships or shift across associations to maximise benefits for themselves. The multiplicity of professional associations contributes different approaches to self-regulation, diluting the political voice through lobbying for competing objectives – particularly around the issue of practitioner regulation (Canaway 2006). The rivalries between particular educational institutions or professional associations, that contribute to schisms and dissensions within the profession, noted in the 1970s (Webb 1977), are still present today (Bensoussan & Myers 1996, Canaway 2007, Lin et al. 2006).

While the position of some professional associations has been consistently against statutory regulation, this does not necessarily reflect the position of members. CAM workforce surveys have found that the majority of Chinese medicine practitioners (Bensoussan & Myers 1996) and naturopathy and WHM practitioners (Bensoussan et al. 2004, Lin et al. 2006) consider government regulation to have more positive than negative implications. For some herbal practitioners, the hope of regaining access to medicinal herbs restricted under drug and poisons legislation after the passage of the Therapeutic Goods Act (1989), is perceived to be a possible outcome of registration. These scheduled herbs can be prescribed by registered medical doctors, but not by the naturopathic and WHM practitioners trained to use them.

Although increasingly accepted by the public, much of the medical profession still demands that evidence of efficacy, preferably through rigorous clinical trials, be provided for CAM therapies. Some within the CAM arena had taken up the call further to incorporate science into education and practice, with the aim of gaining government accreditation and ultimately practitioner registration (Jacka 1998). However, such moves have also contributed to conflict within CAM professions, as bridging of practice paradigms through the incorporation of science has been perceived to be serving the medical profession rather than preserving the autonomy and professional identity of CAM practitioners (Canaway 2007).

During the 1990s, the context for CAM policy development changed, reflecting changes in social trends as well as approaches to health policy making.

This period saw a number of important developments:

- health policy processes became more open, particularly to consumer participation

- social movements – particularly the women’s movement – became critical of the dominance of biomedical models of healthcare

- governments moved generally towards deregulation while setting up clear frameworks for when occupational regulation would be considered.

- social movements – particularly the women’s movement – became critical of the dominance of biomedical models of healthcare

The rise of consumer preferences for CAM has coincided with these developments, if not reflecting these broader social trends. At the same time, the consumerist ideology has also been used by government – of both the social welfarist and neo-liberal orientation – to instigate reforms in the health system (Shiell & Carter 1998).

Kingdon’s model of agenda setting suggests that the window of opportunity for policy to be made occurs when the different streams of policy problems, policy solutions, and ‘political will’ come together (Kingdon 1984). Sometimes policy problems exist, but policy solutions are not obvious. Often, policy problems persist, and policy solutions are available, but there is little political will to act. The window of opportunity for political will to be exercised for policy development relies in part on the existence of policy entrepreneurs or champions who are able to bring the players and the arguments together within the right context.

In the case of the registration of CAM practitioners, Kingdon’s model provides a plausible explanation of the policy process that occurred. In the case of Victoria, the lengthy process of policy research and policy development allowed for the alignment of the diverse political forces within the profession as well as across broader political divides (Carlton 2005). The reporting of adverse events in the media raised the question of whether governments should step in to protect public health and safety and has been the trigger for both the review of Chinese medicine in the mid 1990s as well as the more recent review of naturopathy and WHM. The presence of Carlton as a policy entrepreneur was also critical for the registration of Chinese medicine. This might explain in part some of the differences across jurisdictions, particularly why Victoria has taken a lead, compared with Western Australia and New South Wales, on Chinese medicine, naturopathy and WHM.

Other factors are also at play, however. In New South Wales, since 2002, there have been three health ministers – Knowles, Iemma, and Hatzistergos – each with differing political imperatives, as well as policy agendas and priorities. Another factor is that within the New South Wales Health Department, responsibility for CAM policy has been with the legislation branch rather than with a branch responsible for workforce policy. Western Australia has similarly experienced a volatile political climate, along with restructuring of the health system. Under these circumstances, registration of CAM practitioners would not become a policy priority in a system concerned largely with managing the operation of public sector healthcare. Neither the political window of opportunity, nor the policy entrepreneur, is evident.

A political window and single policy entrepreneur remain insufficient, however. Policy advocacy coalition theory (Sabatier & Jenkins-Smith 1993) suggests an alignment of different social forces – through a policy network – is needed for policy action to be taken. This might also explain some of the differences across jurisdictions and across professions. Within Victoria, for Chinese medicine, a more coherent voice from within the profession – including academics and practitioners – provided strong support for the policy development process. The State Administration for Traditional Chinese Medicine from China also paid numerous courtesy calls at senior levels of government. Additionally, Victoria has had a tradition of a consumer-oriented approach to health policy since the inception of the Labor government in the mid 1980s, reflected also in their reforms to health practitioner regulation in the early 1990s, as well as the system-wide review of 2002 (DHS 2003, 2005) and subsequent Health Professions Registration Act 2005.

The voices for naturopathy and WHM have been different. While CAM practices are recognised by a range of institutions, such as private health funds or professional indemnity organisations, and are increasingly of interest to GPs, the conflict and dissent within the profession – including debates about the different paradigms of healing – probably have contributed to the slow response by governments.

The political ‘deal’ to assure the passage of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) legislation in 1999 reflects the increased popular acceptance of CAM as well as political lobbying by CAM groups. However, no system for professional standard-setting was created, despite government making available $500,000 to be divided between five CAM professional associations for establishing a uniform national registration scheme for suitably qualified practitioners. Despite policy research recommending statutory registration for naturopaths and WHM practitioners (by Lin et al. 2006), the absence of a coherent policy advocacy coalition might diminish the political will needed to implement this recommendation.

Health policy reflects the coming together of different rationalities, where research evidence, political imperatives, and community values coincide (Lin 2005, see also Ch 2). This might also explain developments across jurisdictions and professions, and might shape future developments. In Victoria, the adverse events reported in the media which triggered policy research, the evidence provided by that research, and the coalition of advocates intersected to produce Chinese medicine registration. In other jurisdictions and for naturopathy and WHM, the existence of other political imperatives means there is less interest to manage the diverse interests represented by a less coherent community of practitioners and academics.

CONCLUSION AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS FOR POLICY DEVELOPMENT

CAM practitioner regulation, historically and today, poses numerous policy problems due to factors such as complex practice boundaries, therapies and healthcare practices drawing from beliefs and principles not necessarily consistent with those of mainstream science and medicine, lack of appropriate research on some areas of CAM practice, and lack of stakeholder consensus as to the regulatory needs of CAM. Many social factors and movements have contributed to the increasing public shift toward use of CAM therapies seen over the past four decades. Concurrent use of CAM and orthodox medicine has been reported by 34–53% of CAM users (Lin et al. 2006, MacLennan et al. 2006). The increasing use of unregulated CAM therapies, which lack provision to enforce minimum educational and practice standards, increases the level of risk to the public. It is on the question of risk, or public health and safety, that new practitioner registration now largely rests, as reflected by the AHMAC criteria.

With the government spotlight focused on the health workforce – that is, new Victorian omnibus legislation governing health practitioner regulation followed by national overhaul of the registration and accreditation systems, will CAM regulation be lost in this complex set of policy development, relegated to the backburner, or be pursued separately as an example of a national approach that leapfrogs state-based development? In the immediate term, the scenarios could range from a single state taking on registration responsibility for all CAM practitioners, to no further action on any CAM practitioner registration (other than for Chinese medicine in Victoria). In all likelihood, the registration of naturopathy and WHM will have to await the resolution of broader national questions about health workforce regulation.

In the longer run, there remains a question of whether consumer preferences for integrated healthcare will be brought into the public sector or be a more significant component of the Australian primary healthcare system. Despite the embracing of CAM, the greater medical orthodoxy generally remains ambivalent toward CAM and its integration into mainstream territory (Eastwood 2002). The main stakeholders in this development are CAM consumers, practitioners, professional associations, and government bodies who ultimately decide if statutory regulation is warranted. Other interest groups include the medical and allied health professions, particularly RACGP, the Australasian Integrative Medicine Association (AIMA) and the Australian Medical Association (AMA) who are now actively involved with CAM. Insurers are also increasingly concerned about their outlays (Lin et al. 2006). The increased involvement of these stakeholders suggests that integrative medicine is likely to be on the agenda, at least in the medium term.

A medical ethicist warns that ‘the sign of the effective regulation of CAM practitioners who purport to manage significant health conditions will be the gradual blurring of the boundaries between orthodox and CAM practice’ (Parker 2003). While potential moves to increase CAM regulation should be made if they are in the public’s best interest, of concern to CAM practitioners will be how these moves are made in light of preserving the professional integrity and identity of CAM professions.