Case 10 Psoriasis

Description of psoriasis

Definition

Psoriasis is a chronic dermatological condition represented by epidermal thickening, hyperplasia, hyperkeratosis and inflammation. Of the two key types of psoriasis, type 1 is the most severe and the most resistant to treatment. Type 1 usually occurs in early adulthood and family history of the disease is common. Type 2 typically manifests in the fifth to sixth decade of life, is less severe and is not related to family history.1 Overlapping these two types of psoriasis are a number of subtypes, including the erythrodermic, guttate, plaque and pustular variants.

Epidemiology

Psoriasis affects between one and five per cent of the population,2 and even though the disease can occur at any age, it has a tendency to peak from late adolescence (i.e. 16 years) to 22 years and again between 57 and 60 years.1

Aetiology and pathophysiology

Psoriasis is a disorder with a firm genetic basis.3 The lifetime prevalence of developing psoriasis in first-degree relatives ranges from four per cent if neither parent has the condition, to twenty-eight per cent if one parent has the condition and up to sixty-five per cent if both parents have psoriasis.4 Additional to this, almost half of sufferers report a positive family history of the condition.5

One factor that may increase the skin’s susceptibility to chronic plaque formation is a reduction in cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) levels. Reduced cAMP elevates proteinase activity, for instance, causing accelerated growth and thickening of the epidermis. Low cAMP levels also increase arachidonic acid production, leukotriene B4 activation, neutrophil migration and epidermal inflammation.6

While changes in the levels of these chemical messengers may be genetically predetermined, they could also be influenced by several physiological factors, including incomplete protein digestion, bowel toxaemia and impaired liver function. According to one theory, inadequate protein digestion elevates the quantity of undigested amino acids in the intestinal lumen, which, upon exposure to intestinal flora, leads to the formation of toxic polyamines and a subsequent reduction in cAMP production.7,8 The presence of gut-derived toxins from intestinal bacteria and fungi is believed to increase levels of cyclic guanidine monophosphate (cGMP), which may, in effect, increase cellular proliferation.8 Although the accumulation of toxins from abnormal digestive or hepatic function might contribute to and/or aggravate the symptoms of psoriasis, there is insufficient evidence to support these mechanisms of action.

Adding to the complexity of this disease are myriad intrinsic and extrinsic triggers of psoriasis. Some of the extrinsic triggers of this disease include alcohol, beta-hemolytic streptococcal infection, epidermal trauma, gluten, sunburn, viral infection and medications, including angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, beta-adrenergic blockers, chloroquine, interferon-alpha, lithium, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and terbinafine.1,2 Intrinsic triggers, such as emotional stress, are considered to be a major aggravating factor of the disease.1,9,10 Exactly how stress affects psoriasis is not clear. Findings from one study suggest it could relate to the adverse effects of cortisol on the immunological and integumentary systems. In this 3-year study of 95 sufferers of progressive psoriasis, stressful life events were found to precede a rise in cortisol levels, which was followed by the development of an infectious illness and the eruption of psoriasis over an average span of 8 weeks.11 Corroborating evidence from larger studies may help to support this stress–psoriasis hypothesis.

Clinical manifestations

Psoriatic lesions and concomitant symptoms of the disease vary according to the type and subtype of psoriasis. Plaque psoriasis is the most common subtype and usually presents as demarcated, erythematous and thickened plaques covered with fine silvery scales. These lesions are often located on the scalp, trunk and extremities, and are frequently accompanied by pruritus and nail pitting. The pustular variant may manifest as erythematous, pustule-studded lesions to the palmar or plantar surfaces, though in some cases can be associated with pyrexia and malaise. Guttate psoriasis presents as distinct, scaly, erythematous, droplet-like lesions to the scalp, ears, face, trunk and proximal limbs. The other major variant, erythrodermic psoriasis, is a dermatological emergency, manifesting as severe and extensive erythema and exfoliation, malaise and reduced skin function. Sufferers of psoriasis can also develop psoriatic arthritis, although this tends to affect a relatively small proportion of psoriasis cases.1,12,13

Rapport

Adopt the practitioner strategies and behaviours highlighted in Table 2.1 (chapter 2) to improve client trust, communication and rapport, as well as the accuracy and comprehensiveness of the clinical assessment.

Medical history

Family history

Father has psoriasis, paternal grandmother has rheumatoid arthritis.

Medications

Calcipotriol/betamethasone diproprionate 50/500 ointment twice a day, coal tar three times a week.

Lifestyle history

Illicit drug use

| Diet and fluid intake | |

| Breakfast | Corn Flakes® with full-cream milk. |

| Morning tea | Coffee. |

| Lunch | Meat pie, white roll with salad, hot chicken roll, iced coffee. |

| Afternoon tea | Coffee. |

| Dinner | Spaghetti bolognaise, meat lover’s pizza, beef schnitzel or sausages with mashed potato and peas. |

| Fluid intake | 1 cup of water daily, 2 cups of iced coffee daily, 1–2 cups of soft drink daily, 1 cup of milk daily, 2–3 cups of instant coffee daily. |

| Food frequency | |

| Fruit | 0–1 serve daily |

| Vegetables | 1–2 serves daily |

| Dairy | 1–2 serves daily |

| Cereals | 4–5 serves daily |

| Red meat | 8 serves a week |

| Chicken | 2 serves a week |

| Fish | 0 serves a week |

| Takeaway/fast food | 8 times a week |

Physical examination

Inspection

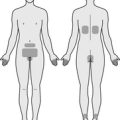

Skin lesions are evident on the scalp and both elbows, anterior knees and buttocks, ranging from 5 to 100 mm in diameter. All plaques are demarcated, erythematous, thickened and covered with fine silvery scales. Excoriation and lichenification are also present around the lesions. There is no exudation, bleeding, papules, pustules or ulceration. Pitting and mild onycholysis is evident to all fingernails.

Diagnostics

Pathology tests

Liver function test (LFT)

The LFT can provide useful information about hepatic function but cannot reliably detect impairments in liver detoxification because elevated blood ammonia, a sign of functional liver impairment, is unlikely to rise above the normal range in mild to moderate hepatic disease.14

Endomysial and gliadin antibodies

The accumulation of undigested gliadin and gluten within the intestinal tract can lead to the formation of immunoglobulin A (IgA) endomysial antibodies, and IgA/IgG gliadin antibodies. Elevated serum levels of these antibodies are suggestive of gluten-sensitive enteropathy,14 a possible trigger of psoriasis.2

Functional tests

The comprehensive detoxification profile (CDP) measures a person’s capacity to effectively clear toxic metabolites from the blood, which may help to ascertain whether impaired liver function is a contributing and/or aggravating factor of psoriasis.15

Invasive tests

A lesion biopsy may be required if a diagnosis of psoriasis is uncertain. Histological findings indicative of psoriatic disease include increased mitosis of endothelial cells, fibroblasts and keratinocytes, evidence of inflammatory cells within the dermis and epidermis, and acanthosis.16

Diagnosis

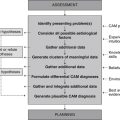

Planning

Goals

Expected outcomes

Based on the degree of improvement reported in clinical studies that have used CAM interventions for the management of psoriasis,17–21 the following are anticipated.

Application

Diet

Gluten-free diet (Level III-2, Strength C, Direction + (for AGA-positive persons only))

There is some suggestion that gluten sensitivity may trigger psoriasis by increasing small intestine permeability and superantigen uptake, and by stimulating the release of cytokines from T-cells.22 This association between gluten and psoriasis is partly supported by findings from a small unblinded study of 36 adults with chronic psoriasis. In patients with antigliadin antibodies (AGA), the 3-month gluten-free diet significantly reduced psoriasis area and severity index scores (p = 0.001, n = 30). This was not the case for patients who were AGA negative (n = 6).20 While it is probable that the elimination of gluten-containing foods such as wheat, triticale, barley, oats and rye may benefit some sufferers of psoriasis, the likelihood of selection and placebo bias in this study raises questions about the validity of these findings.

High-antioxidant diet (Level III-2, Strength C, Direction +)

Findings from a multicentre, case–control study suggest the consumption of high antioxidant and flavonoid content foods may improve the symptoms of psoriasis, possibly by modulating inflammation and oxidative stress. The study, which involved 316 patients with psoriasis and 366 controls, found that the consumption of fresh fruit, carrots, tomatoes and beta-carotene significantly reduced the odds of developing psoriasis (p<0.05), while green vegetable intake demonstrated a marginally significant risk reduction (p = 0.05).23 Whether beta-carotene supplementation or the consumption of a prescribed high antioxidant diet can yield similar findings in clinical practice warrants further investigation.

High-fibre diet (Level III-3, Strength D, Direction o)

The adequate consumption of soluble and insoluble fibre from sources such as wholegrain cereals, fruits, vegetables, legumes, nuts, seeds and psyllium may be helpful in reducing colon pH and microbial overgrowth, bowel transit time and bowel toxaemia. Then again, when the dietary intake of 136 Norwegian men and women with stable plaque psoriasis was compared to a reference group of Norwegians without psoriasis, neither fibre nor any other dietary component was found to be correlated with psoriasis area and severity index (PASI) scores.24 Without prospective data from controlled clinical trials it is difficult to determine whether the administration of therapeutic doses of fibre has any effect on psoriasis area and severity.

Lifestyle

Abstinence from alcohol (Level III-2, Strength C, Direction +)

The consumption of alcohol can cause blood histamine levels to rise,23 which, in susceptible individuals, could aggravate the symptoms of psoriasis. This association between alcohol intake and psoriasis surface area and severity is supported by a number of studies,25,26 and is particularly evident among male sufferers. While there is a paucity of evidence from intervention studies, it is probable that the abstinence from or moderate intake of alcohol may help to reduce the severity of psoriasis.

Meditation (Level II, Strength B, Direction +)

Emotional stress is a major intrinsic trigger of psoriasis. Thus, it would be reasonable to assume that effective stress management could facilitate remission of the disease. To test this assumption, 37 patients undergoing phototherapy or photochemotherapy for psoriasis were randomly assigned to receive audiotape-guided mindfulness meditation or a non-tape control in conjunction with light therapy. Under RCT conditions, audiotape-guided mindfulness meditation significantly increased the rate of resolution of psoriatic lesions when compared to the non-tape control.19 This corroborates findings from an earlier trial (n = 24) that found meditation and a combination of meditation and imagery to be significantly superior to waiting-list and no treatment controls in reducing psoriasis severity scores at 20 weeks.18 Studies comparing stress management and guided imagery to no treatment27 or relaxation therapy to no treatment28 have been inconclusive with regards to changes in psoriasis symptoms. Further research into the effectiveness of other stress-reduction strategies on psoriasis, such as yoga, tai chi and progressive muscle relaxation, is now required.

Sunlight (Level III-1, Strength D, Direction o)

Sun exposure is often recommended to patients with psoriasis to facilitate recovery. Even though several clinical trials have shown ultraviolet B (UVB) radiation and a combination of ultraviolet A (UVA) radiation and the photosensitising agent psoralen to be effective at reducing the surface area of psoriasis,29 the evidence for natural sunlight is less convincing. Some studies have found the combination of sunlight and psoralen to be more effective than natural sunlight and placebo at improving psoriasis surface area,29 although these studies predate 1982 and have major methodological limitations. The paucity of rigorous clinical evidence in this area, together with the amplified risk of skin cancer from increasing sun exposure, suggests practitioners should exercise some caution in recommending this therapy. Encouraging clients to limit sunlight exposure to less than 5 minutes a day in summer and 15–20 minutes a day in winter, for instance, minimises this risk while also addressing the importance of vitamin D in psoriasis and the role of sunlight in enhancing endogenous vitamin D synthesis.

Nutritional supplementation

Folic acid (Level III-2, Strength C, Direction o)

Low plasma folate levels have been shown to be inversely related to psoriasis area and severity.30 Folate antagonists, such as methotrexate, can be prescribed for the management of this disease and may be an associated factor; however, because folate antagonists are effective at improving the symptoms of psoriasis31 and folic acid may reduce the effectiveness of these drugs,32 it is advised that folic acid supplementation be withheld while a patient is being treated with a folate antagonist.

Omega 3 fatty acids (Level II, Strength B, Direction + (intravenous use only))

The anti-inflammatory effects of omega 3 polyunsaturated fatty acids have been well documented in population and clinical studies,33 although evidence of the effectiveness of orally and topically administered omega 3 fatty acids in psoriasis has been inconsistent. RCTs reporting significant improvements in the surface area and severity of guttate and plaque psoriasis have only been demonstrated with intravenous omega 3 fatty acids.34,35 This route of administration has limited application in conventional CAM practice.

Selenium (Level III-1, Strength C, Direction o)

Selenium plays a pivotal role in the regulation of inflammation and immunity, specifically, the inhibition of nuclear factor-kappaB activation36 and the enhancement of T-cell function and B-cell activation and proliferation.37 In spite of these actions, evidence from a double-blind controlled trial has shown the administration of 600 μg of selenium for 12 weeks had no statistically significant effect on the severity of psoriasis when compared with placebo.38 It would be premature to make any firm conclusions about the effectiveness of selenium in psoriasis until further research emerges.

Vitamin A (Level I, Strength A, Direction +)

Vitamin A is one of several systemic medical treatments used in the treatment of severe psoriasis. This may be because vitamin A plays a key role in normal epithelial cell differentiation and collagen synthesis,39 but more so because the treatment is supported by six RCTs. A systematic review of these trials found that when compared with placebo, synthetic oral retinoids (75 mg a day) were moderately effective at reducing the surface area and severity of psoriasis.29 Given that these findings may not be representative of the effects of natural vitamin A or beta-carotene, clinicians should be cautious about using these agents as a substitute for synthetic retinoids.

Vitamin B12 (Level II, Strength D, Direction o)

Vitamin B12 plays an important role in immunomodulation. Experimental data show that this vitamin stimulates helper and suppressor T-cell activity40 and suppresses T-cell cytokine production.41 Although these effects may not necessarily manifest in humans, they provide some explanation for the outcomes of a small RCT in 13 patients with plaque psoriasis. The study found the application of a vitamin B12 and avocado oil cream for 12 weeks to be as effective as calcipitriol treatment (a vitamin D derivative) at reducing the severity of psoriasis.42 Given the small sample size, questionable control and the confounding effect of the avocado oil, these results should be interpreted with caution.

Vitamin D (Level II, Strength A, Direction + (topical use only))

Vitamin D exhibits a range of antipsoriatic effects, including anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory and keratinocytic activity. Specifically, experimental data have shown that vitamin D downregulates the expression of tissue necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin (IL)-6, IL-1 and IL-8 in monocytes,43 reduces keratinocyte proliferation and increases cell differentiation.29 Evidence from a number of RCTs supports these data, with topically administered synthetic vitamin D3 analogues found to be significantly more effective than placebo at reducing the symptoms and severity of plaque psoriasis.44–46 Despite these encouraging results, these effects are not likely to be representative of orally administered vitamin D and, as such, may not be applicable to conventional CAM practice.

Zinc (Level III-1, Strength C, Direction o)

Zinc is frequently recommended as a treatment for integumentary disorders, possibly due to the anti-inflammatory, vulnerary and immunomodulatory effects of the mineral, in particular, the capacity to reduce spontaneous cytokine release and improve T-cell response.47 As a treatment for psoriasis, the evidence is not so convincing. First, it is uncertain whether psoriatic sufferers require zinc supplementation; one study reported low epidermal zinc levels in sufferers48 and a number of clinical studies demonstrated similar serum zinc levels between sufferers and healthy controls.49,50 The lack of understanding about the role of zinc in this disorder may explain why oral zinc supplementation has failed to demonstrate a clinical benefit in psoriasis in studies to date.51,52

Herbal medicine

Aloe barbadensis (Level II, Strength C, Direction o)

Aloe vera was traditionally used in Western herbal medicine as a vulnerary, anti-inflammatory and immunostimulant agent. While a number of clinical studies have investigated the effect of this plant in psoriasis, the findings have not been consistent. In a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of sixty adults with mild to moderate plaque psoriasis, for example, the application of 0.5 per cent aloe vera gel three times a day, 5 days a week for a maximum of 4 weeks, was found to be significantly more effective than placebo at reducing the severity, redness and number of psoriatic lesions.53 This is in contrast to an RCT of 41 adults with plaque psoriasis that found topically administered aloe vera gel twice daily for 4 weeks to be significantly less effective than placebo gel at reducing the symptoms of psoriasis (p = 0.02).54 Differences in the frequency of application of aloe may have contributed to these incongruent findings.

Azadirachta indica (Level III-1, Strength C, Direction +)

The anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory and antimicrobial effects of neem leaf have been demonstrated in a number of experimental studies.55–57 These effects have been further supported by evidence from a double-blind placebo-controlled trial. This small study of 44 patients with plaque psoriasis showed the oral administration of an aqueous extract of neem leaves (three times a day for 4 weeks), together with the application of five per cent coal tar ointment (twice a day for 4 weeks), was significantly more effective than placebo and coal tar at reducing psoriasis surface area and severity (p<0.001).58 As a cautionary note to Australian practitioners, the use of Azadirachta in Australia is restricted to topical use only. These findings therefore may not be relevant to CAM practice in Australia or in other countries with similar restrictions on use.

Berberis aquifolium (Level II, Strength B, Direction + (topical use only))

Oregon grape was traditionally used as a treatment for psoriasis, possibly due to the depurative, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial and antipsoriatic effects of the plant. Emerging evidence from clinical trials corroborates this traditional body of knowledge. To exemplify this point, two 12-week, double-blind placebo controlled trials have consistently shown that when compared with placebo, topically administered Oregon grape significantly improves psoriasis symptoms and quality of life.17,21 Findings from another RCT point out that Oregon grape ointment might benefit psoriasis by improving cellular cutaneous immune mechanisms and keratinocyte hyperproliferation.59

Other

Acupuncture (Level II, Strength B, Direction o)

Acupuncture originated in China more than 4000 ago.60 Since then, a large traditional evidence base for the therapy has been established. Positive findings from case reports have since added to this traditional knowledge, particularly in the area of psoriasis.61 An RCT of 56 patients with chronic plaque psoriasis challenges this body of evidence; it showed classical acupuncture together with auricular acupuncture twice a week for 10 weeks to be no more effective than sham acupuncture at improving psoriasis area and severity.62

CAM prescription

The CAM interventions that are most appropriate for the management of the presenting case – that is, they target the planned goals, expected outcomes and CAM diagnoses, they are supported by the best available evidence, they are pertinent to the client’s needs and they are most relevant to CAM practice – are outlined below.

Primary treatments

Secondary treatments

Referral

1. Weller P.A. Psoriasis. In Marks R., editor: Dermatology, 2nd ed, Sydney: Australasian Medical Publishing Company, 2005.

2. Porter R., et al, editors. The Merck manual. Rahway: Merck Research Laboratories, 2008.

3. Gudjonsson J.E. Genetic variation and psoriasis. Giornale Italiano di Dermatologia e Venereologia. 2008;143(5):299-305.

4. Swanbeck G., et al. Genetic counselling in psoriasis: empirical data on psoriasis among first-degree relatives of 3095 psoriatic probands. British Journal of Dermatology. 1997;137(6):939-942.

5. Altobelli E., et al. Family history of psoriasis and age at disease onset in Italian patients with psoriasis. British Journal of Dermatology. 2007;156(6):1400-1401.

6. Rubin R., Strayer D.S. Rubin’s pathology: clinicopathologic foundation of medicine, 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2007.

7. Clo C., et al. Polyamines and cellular adenosine 3‘:5’-cyclic monophosphate. Biochemical Journal. 1979;182(3):641-649.

8. Pizzorno J.E., Murray M.T. Textbook of natural medicine, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2006.

9. O’Leary C.J., et al. Perceived stress, stress attributions and psychological distress in psoriasis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2004;57(5):465-471.

10. Zachariae R., et al. Self-reported stress reactivity and psoriasis-related stress of Nordic psoriasis sufferers. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 2004;18(1):27-36.

11. Weigl B.A. The significance of stress hormones (glucocorticoids, catecholamines) for eruptions and spontaneous remission phases in psoriasis. International Journal of Dermatology. 2000;39(9):678-688.

12. Buchanan P., Courteney M. Prescribing in dermatology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2006.

13. Levine N. Dermatology: diseases and therapy. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2007.

14. Pagana K., Pagana T. Mosby’s diagnostic and laboratory test reference, 7th ed. St Louis: Elsevier Mosby; 2005.

15. Liska D., Lyon M., Jones D.S. Detoxification and biotransformational imbalances. Explore: Journal of Science and Healing. 2006;2(2):122-140.

16. Tuchman M., Buchholz R., Weinberg J.M. Psoriasis. In Hall J.C., editor: Sauer’s manual of skin diseases, 9th ed, Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2006.

17. Bernstein S., et al. Treatment of mild to moderate psoriasis with Relieva, a Mahonia aquifolium extract: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. American Journal of Therapeutics. 2006;13(2):121-126.

18. Gaston L., et al. Psychological stress and psoriasis: experimental and prospective correlational studies. Acta Dermato-Venereologica. 1991;156:37-43.

19. Kabat-Zinn J., et al. Influence of a mindfulness meditation-based stress reduction intervention on rates of skin clearing in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis undergoing phototherapy (UVB) and photochemotherapy (PUVA). Psychosomatic Medicine. 1998;60(5):625-632.

20. Michaelsson G., et al. Psoriasis patients with antibodies to gliadin can be improved by a gluten-free diet. British Journal of Dermatology. 2000;142(1):44-51.

21. Wiesenauer M., Ldtke R. Mahonia aquifolium in patients with Psoriasis vulgaris: an intraindividual study. Phytomedicine. 1996;3:231-235.

22. Wolters M. Diet and psoriasis: experimental data and clinical evidence. British Journal of Dermatology. 2005;153:706-714.

23. Naldi L., et al. Dietary factors and the risk of psoriasis: results of an Italian case-control study. British Journal of Dermatology. 1996;134(1):101-106.

24. Solvoll K., et al. Dietary intake in relation to clinical status in patients with psoriasis. British Journal of Nutrition. 1997;77:337-344.

25. Behnam S.M., Behnam S.E., Koo J.Y. Alcohol as a risk factor for plaque-type psoriasis. Cutis. 2005;76(3):181-185.

26. Kirby B., et al. Alcohol consumption and psychological distress in patients with psoriasis. British Journal of Dermatology. 2008;158(1):138-140.

27. Zachariae R., et al. Effects of psychologic intervention on psoriasis: a preliminary report. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1996;34(6):1008-1015.

28. Keinan G., et al. Stress management for psoriasis patients: the effectiveness of biofeedback and relaxation techniques. Stress Medicine. 1995;11(4):235-241.

29. Griffiths C.E.M., et al. A systematic review of treatments for severe psoriasis. Health Technology Assessment Monograph. Norwich: HMSO; 2000.

30. Malerba M., et al. Plasma homocysteine and folate levels in patients with chronic plaque psoriasis. British Journal of Dermatology. 2006;155(6):1165-1169.

31. Flytstrom I., et al. Methotrexate vs. ciclosporin in psoriasis: effectiveness, quality of life and safety: a randomized controlled trial. British Journal of Dermatology. 2008;158(1):116-121.

32. Salim A., et al. Folic acid supplementation during treatment of psoriasis with methotrexate: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. British Journal of Dermatology. 2006;154(6):1169-1174.

33. Jho D.H., et al. Role of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation in inflammation and malignancy. Integrative Cancer Therapies. 2004;3(2):98-111.

34. Grimminger F., et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of n-3 fatty acid based lipid infusion in acute, extended guttate psoriasis: rapid improvement of clinical manifestations and changes in neutrophil leukotriene profile. Clinical Investigator. 1993;71(8):634-643.

35. Mayser P., et al. Omega-3 fatty acid-based lipid infusion in patients with chronic plaque psoriasis: results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1998;38(4):539-547.

36. Vunta H., et al. The anti-inflammatory effects of selenium are mediated through 15-deoxy-Delta12, 14-prostaglandin J2 in macrophages. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282(25):17964-17973.

37. Hawkes W.C., Kelley D.S., Taylor P.C. The effects of dietary selenium on the immune system in healthy men. Biological Trace Element Research. 2001;81(3):189-213.

38. Fairris G.M., et al. The effect of supplementation with selenium and vitamin E in psoriasis. Annals of Clinical Biochemistry. 1989;26(1):83-88.

39. Leach M.J. A critical review of natural therapies in wound management. Ostomy/Wound Management. 2004;50(2):36-51.

40. Sakane T., et al. Effects of methyl-B12 on the in vitro immune functions of human T lymphocytes. Journal of Clinical Immunology. 1982;2:101-109.

41. Yamashiki M., Nishimura A., Koska Y. Effects of methylcobalamin (vitamin B12) on in vitro cytokine production of peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Journal of Clinical Laboratory Immunology. 1992;37:173-182.

42. Stucker M., et al. Vitamin B12 cream containing avocado oil in the therapy of plaque psoriasis. Dermatology. 2001;203:141-147.

43. Giulietti A., et al. Monocytes from type 2 diabetic patients have a pro-inflammatory profile. 1,25- Dihydroxyvitamin D(3) works as anti-inflammatory. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 2007;77(1):47-57.

44. Helfrich Y.R., et al. Topical becocalcidiol for the treatment of psoriasis vulgaris: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, multicentre study. British Journal of Dermatology. 2007;157(2):369-374.

45. Lebwohl M., et al. Calcitriol 3 microg/g ointment in the management of mild to moderate plaque type psoriasis: results from 2 placebo-controlled, multicenter, randomized double-blind, clinical studies. Journal of Drugs in Dermatology. 2007;6(4):428-435.

46. Van de Kerkhof P.C., et al. Tacalcitol ointment in the treatment of psoriasis vulgaris: a multicentre, placebo-controlled, double-blind study on efficacy and safety. British Journal of Dermatology. 1996;135(5):758-765.

47. Kahmann L., et al. Zinc supplementation in the elderly reduces spontaneous inflammatory cytokine release and restores T-cell functions. Rejuvenation Research. 2008;11(1):227-237.

48. Michaelsson G., Ljunghall K. Patients with dermatitis herpetiformis, acne, psoriasis and Darier’s disease have low epidermal zinc concentrations. Acta Dermato-Venereologica. 1990;70(4):304-308.

49. Kreft B., et al. Analysis of serum zinc level in patients with atopic dermatitis, psoriasis vulgaris and in probands with healthy skin. Hautarzt. 2000;51(12):931-934.

50. Ozturk G., et al. Natural killer cell activity, serum immunoglobulins, complement proteins, and zinc levels in patients with psoriasis vulgaris. Immunological Investigations. 2001;30(3):181-190.

51. Burrows N.P., et al. A trial of oral zinc supplementation in psoriasis. Cutis. 1994;54(2):117-118.

52. Leibovici V., et al. Effect of zinc therapy on neutrophil chemotaxis in psoriasis. Israel Journal of Medical Sciences. 1990;26(6):306-309.

53. Syed T.A., et al. Management of psoriasis with Aloe vera extract in a hydrophilic cream: a placebo-controlled, double-blind study. Tropical Medicine and International Health. 1996;1(4):505-509.

54. Paulsen E., Korsholm L., Brandrup F. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of a commercial Aloe vera gel in the treatment of slight to moderate psoriasis vulgaris. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 2005;19(3):326-331.

55. Beuth J., Schneider H., Ko H.L. Enhancement of immune responses to neem leaf extract (Azadirachta indica) correlates with antineoplastic activity in BALB/c-mice. Vivo. 2006;20(2):247-251.

56. Bone K. A clinical guide to blending liquid herbs. St Louis: Churchill Livingstone; 2003.

57. Chattopadhyay R.R. Possible biochemical mode of anti-inflammatory action of Azadirachta indica A. Juss. in rats. Indian Journal of Experimental Biology. 1998;36(4):418-420.

58. Pandey S.S., Jha A.K., Kaur V. Aqueous extract of neem leaves in treatment of psoriasis vulgaris. Indian Journal of Dermatology. Venereology and Leprology. 1994;60(2):63-67.

59. Augustin M., et al. Effects of Mahonia aquifolium ointment on the expression of adhesion, proliferation, and activation markers in the skin of patients with psoriasis. Forschende Komplementarmedizin. 1999;6(Suppl 2):19-21.

60. O’Brien K.A., Xue C.C. Acupuncture. In: Robson T., editor. An introduction to complementary medicine. Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 2003.

61. Liao S.J., Liao T.A. Acupuncture treatment for psoriasis: a retrospective case report. Acupuncture and Electro-Therapeutics Research. 1992;17(3):195-208.

62. Jerner B., Skogh M., Vahlquist A. A controlled trial of acupuncture in psoriasis: no convincing effect. Acta Dermato-Venereologica. 1997;77(2):154-156.