CASE 10 PCI of an Ostial Right Coronary Artery Lesion

Cardiac catheterization

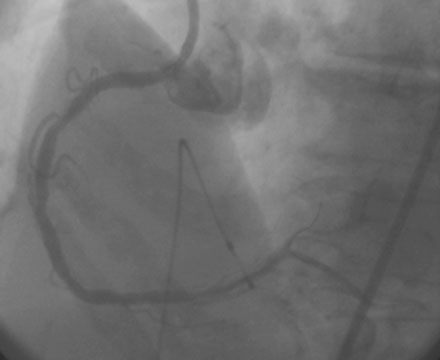

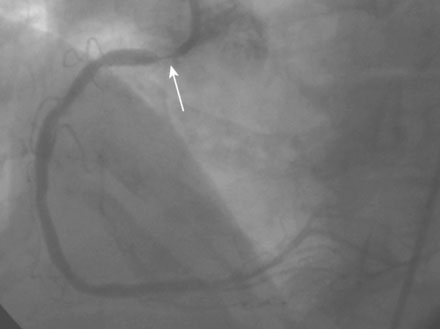

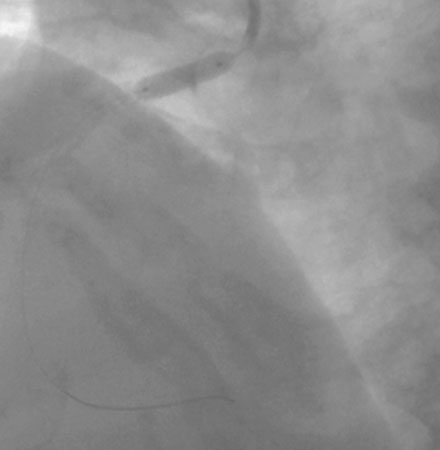

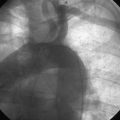

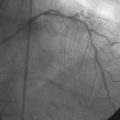

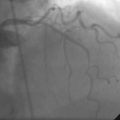

Coronary angiography found no significant obstructive disease in the left coronary artery (Figure 10-1) but a severe ostial stenosis of the right coronary artery, with extensive calcification (Figure 10-2 and Video 10-1). Based on the angiogram, her physician decided to proceed with a percutaneous approach and, anticipating great difficulty because of the ostial location and the degree of calcification observed, the operator planned to debulk the lesion with rotational atherectomy.

FIGURE 10-1 This is the left coronary angiogram; there were no significant obstructive lesions noted.

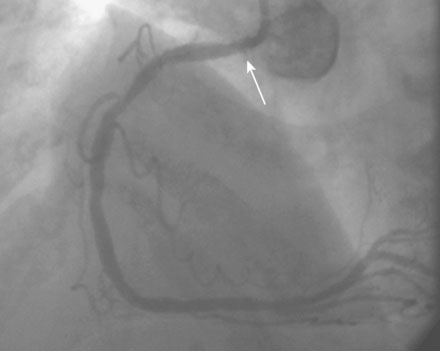

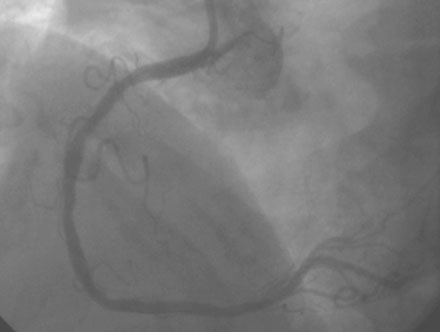

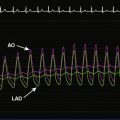

Femoral venous access was obtained and a temporary pacemaker wire positioned in the right ventricular apex. The operator then engaged an 8 French right Judkins guide catheter with side holes and administered eptifibatide as a double bolus plus infusion along with unfractionated heparin to achieve an activated clotting time (ACT) greater than 200 seconds. A floppy-tipped rotational atherectomy guidewire was positioned distally in the right coronary artery. Rotational atherectomy was accomplished first with a 1.5 mm burr, followed by a 2.0 mm burr. The angiographic result after rotational atherectomy is shown in Figure 10-3 and Video 10-2. The operator removed the rotational atherectomy guidewire and positioned a conventional 0.014 inch floppy-tipped guidewire distally in the right coronary artery. The lesion was dilated with a 3.0 mm diameter by 20 mm long compliant balloon and a 3.5 mm diameter by 23 mm long sirolimus-eluting stent positioned to cover the ostium (Figure 10-4 and Video 10-3) and postdilated with a 4.0 mm diameter by 9 mm long noncompliant balloon to high pressures. The final angiographic images satisfied the operator, although mild narrowing remained at the ostium (Figure 10-5 and Video 10-4); intravascular ultrasound was not performed and the procedure was terminated.

Postprocedural course

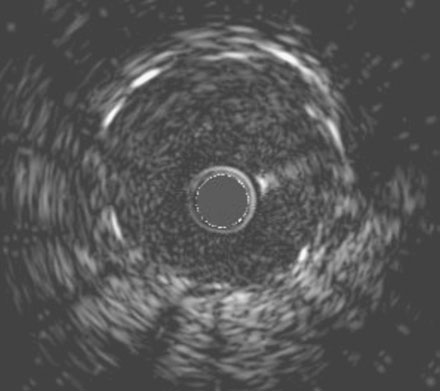

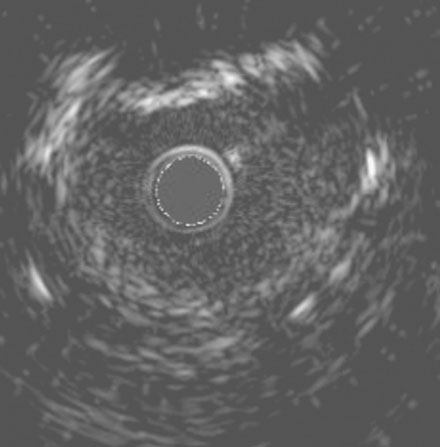

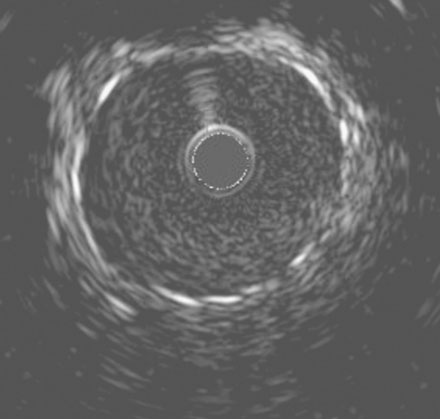

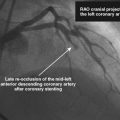

She remained symptom-free for 5 months, and then developed recurrent severe chest pain similar to her initial symptoms. She was again admitted to the hospital, but this time, serial troponins were negative. Repeat cardiac catheterization revealed severe, in-stent restenosis of the ostium of the right coronary artery (Figure 10-6 and Video 10-5). Her physician decided to treat this lesion percutaneously with a cutting balloon. Using bivalirudin as the procedural anticoagulant, the operator dilated the stenosis with a 3.5 mm diameter cutting balloon followed by a 4.0 mm noncompliant balloon to high pressures. Although the angiographic result appeared acceptable (Figure 10-7), there remained a gentle narrowing of the ostium. Intravascular ultrasound was performed and demonstrated excellent stent expansion distally (Figure 10-8), but the ostium remained deformed with a 7 mm2 minimal lumen area, despite aggressive balloon dilatation (Figure 10-9). In order to treat this apparent recoil, the operator placed a 4.5 mm diameter by 13 mm long bare-metal stent and expanded it to high pressures (Figure 10-10). The angiographic result appeared much improved (Figure 10-11 and Video 10-6); importantly, the post-stent intravascular ultrasound images showed wide expansion of the stent at the ostium (Figure 10-12).

Discussion

The acute technical success for percutaneous interventions of aorto-ostial lesions is very high, but restenosis rates are higher as compared to similar lesions that do not involve the ostium.1 As demonstrated in this case, there is a high restenosis rate for right coronary artery ostial lesions as compared to left main stem ostial lesions; the mechanism, by intravascular ultrasound studies, appears to be stent recoil as well as neointimal formation.2

Some operators advocate pre-stenting rotational atherectomy or cutting balloon angioplasty to reduce the elastic recoil component, theoretically improving the long-term results for ostial lesions.3 Currently, there are little data and no randomized controlled data to support this strategy for the treatment of aorto-ostial lesions. This strategy did not appear effective in this case.

Similar to other lesion subsets, drug-eluting stents reduce the rate of restenosis for aorto-ostial lesions as compared to bare-metal stents.4,5 However, as shown in this case, restenosis remains a significant problem.

Several important technical tricks may improve the operator’s success. Incomplete coverage of the ostium is the most commonly encountered mistake during treatment of these challenging lesions. This is often due to the previously mentioned difficulty in accurately imaging the true ostium by angiography. In addition, if the operator “overshoots,” causing an excessive length of the stent to protrude into the aorta, it may create difficulties with re-engagement later on. One trick to ensure coverage of the ostium involves the “stent tail wire” technique in which another 0.014 inch guidewire (the tail anchor wire) is placed alongside the stent catheter and inserted behind the last strut. The stent, along with the attached tail anchor wire, is advanced along the guidewire already in place in the coronary artery positioned in the ostium. The tail anchor wire does not enter the coronary artery, but instead straddles the aorto-ostium and helps identify the exact location of the aorto-ostium.6

1. Mavromatis M., Ghazzal Z., Veledar E., Diamandopoulos L., Weintraub W.S., Douglas J.S., Kalynych A.M. Comparison of outcomes of percutaneous coronary intervention of ostial versus nonostial narrowing of the major epicardial coronary arteries. Am J Cardiol. 2004;94:583-587.

2. Tsunoda T., Nakamura M., Wada M., Ito N., Kitagawa Y., Shiba M., Yajima S., Iijima R., Nakajima R., Yamamoto M., Takagi T., Yoshitama T., Anzai H., Nishida T., Yamaguchi T. Chronic stent recoil plays an important role in restenosis of the right coronary ostium. Coron Artery Dis. 2004;15:39-44.

3. Motwani J.G., Raymone R.E., Franco I., Ellis S.G., Whitlow P.L. Effectiveness of rotational atherectomy of right coronary artery ostial stenosis. Am J Cardiol. 2000;85:563-567.

4. Iakovou I., Ge L., Michev I., Sangiorgi G.M., Montorfano M., Airoldi F., Chieffo A., Stankovic G., Vitrella G., Carlino M., Corvaja N., Briguori C., Colombo A. Clinical and angiographic outcome after sirolimus-eluting stent implantation in aorto-ostial lesions. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:967-971.

5. Park D.W., Hong M.K., Suh I.W., Hwang E.S., Lee S.W., Jeong Y.H., Kim Y.H., Lee C.W., Kim J.J., Park S.W., Park S.J. Results and predictors of angiographic restenosis and long-term adverse cardiac events after drug-eluting stent implantation for aorto-ostial coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:760-765.

6. Kern M.J., Ouellette D., Frianeza T. A new technique to anchor stents for exact placement in ostial stenoses: The stent tail wire or Szabo technique. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2006;68:901-906.