Nasopharyngeal Airway Insertion

Nasopharyngeal airways are used to maintain a patent airway to the hypopharynx and to facilitate the removal of tracheobronchial secretions by directing the catheter and by averting tissue trauma that is associated with repeated suction attempts.4

PREREQUISITE NURSING KNOWLEDGE

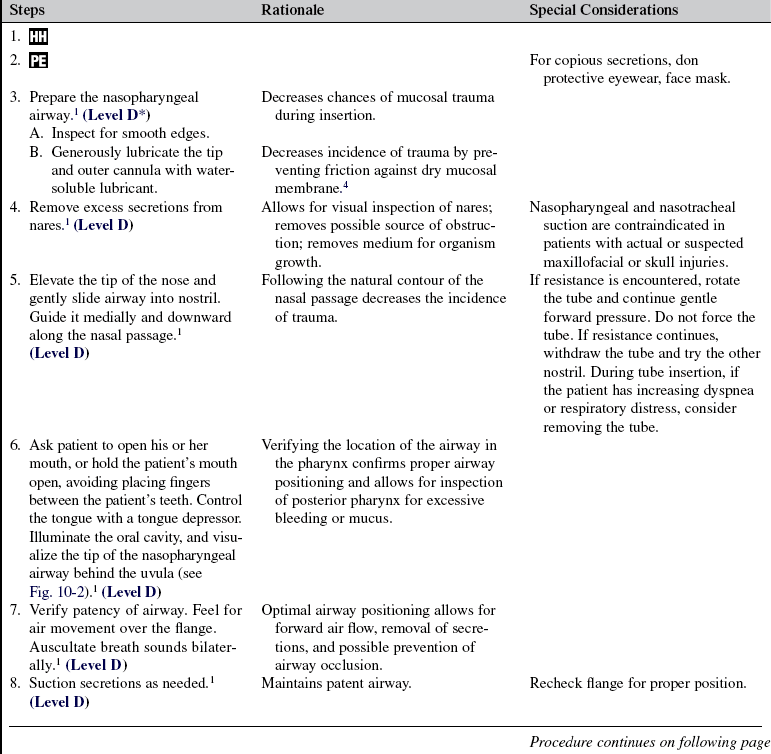

• Nasopharyngeal airways are passed through the nose and follow the posterior nasal and oropharyngeal walls to the base of the tongue (Fig. 10-1).3

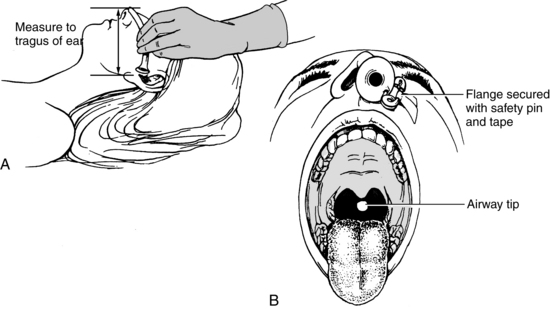

FIGURE 10-1 Nasopharyngeal airway. A, Airway parts. B, Proper placement. (From Eubanks DH, Bone RC: Comprehensive respiratory care: a learning system, St Louis, 1990, Mosby, 518.)

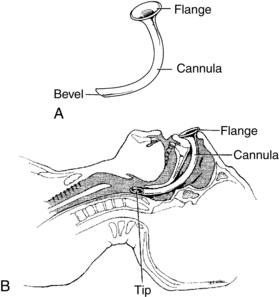

• The nasopharyngeal airway has three parts: the flange, cannula, and bevel or tip. The flange is the wide trumpet-like end that prevents further slippage into the airway. The hollow shaft of the cannula permits airflow into the hypopharynx. The bevel or tip is the opening at the distal end of the tube. When properly inserted, and the correct size, the tip can be seen resting posterior to the base of the tongue.

• The external diameter of the nasopharyngeal airway should be slightly smaller than the patient’s external nares opening. The length of the nasopharyngeal airway is determined by measuring the distance between the naris and the tragus of the ear (Fig. 10-2).2 Improperly sized nasopharyngeal airways may result in increased airway resistance, limited airflow (if the airway is too small), kinking and mucosal trauma, gagging, vomiting, and gastric distention (if the airway is too large). Some manufacturers provide nasopharyngeal airways shaped specifically for the right and left nares.

FIGURE 10-2 A, Estimating nasopharyngeal airway size. B, Nasopharyngeal position after insertion. (From Eubanks DH, Bone RC: Comprehensive respiratory care: a learning system, St Louis, 1990, Mosby, 552.)

• The advantages of the nasopharyngeal airway include increased comfort and tolerance in a conscious patient, stable airway positioning for long periods, decreased incidence of gag reflex stimulation, and minimal incidence of mucosal trauma during frequent suctioning.

• Nasopharyngeal airways are especially useful for relieving airway obstruction associated with mandibular-type injuries that result in jaw immobility or soft tissue obstruction. Examples of these injuries include jaw wiring, trismus, pain, edema, jaw spasms, and mechanical impairment such as temporomandibular joint fractures and zygomatic fractures. In selected patient situations, a nasopharyngeal airway may be used to facilitate the passage of a fiberoptic bronchoscope and to tamponade small bleeding blood vessels in the nasal mucosa.

• Insertion of the nasopharyngeal airway in an alert patient may stimulate the gag reflex and cause retching and vomiting.

• The nasopharyngeal airway is used most commonly in the postanesthesia recovery period to facilitate pulmonary toilets and in situations in which the patient is semiconscious.

• Contraindications to use of a nasopharyngeal airway are as follows:

EQUIPMENT

• Appropriately sized nasal airway (Table 10-1)

TABLE 10-1

| Approximate Body Weight | Size (mm) |

| Small adult | 6 to 7 |

| Medium adult | 7 to 8 |

| Large adult | 8 to 9 |

(From Cummins RO, editor: Airway, airway adjuncts, oxygenation, and ventilation. In ACLS: principles and practice, Dallas, 2003, American Heart Association, 145-146.)

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION

• Explain the purpose of the airway and the necessity of the procedure to conscious patients or to the family of an unconscious patient.  Rationale: Communication and explanation regarding therapy are cited as important needs of patients and families to relieve anxiety and encourage communication.

Rationale: Communication and explanation regarding therapy are cited as important needs of patients and families to relieve anxiety and encourage communication.

• Explain the patient’s role in assisting with insertion of the airway.  Rationale: Patient cooperation is elicited, and tube insertion is facilitated.

Rationale: Patient cooperation is elicited, and tube insertion is facilitated.

• Discuss the sensory experiences associated with nasal airway insertion, including the presence of an airway in the nose and possible gagging.  Rationale: Knowledge of anticipated sensory experiences reduces anxiety and distress.

Rationale: Knowledge of anticipated sensory experiences reduces anxiety and distress.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT AND PREPARATION

Patient Assessment

• Verify correct patient with two identifiers.  Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

• Assess cardiopulmonary status.  Rationale: Evaluation of the patient’s cardiopulmonary status assists in determining the need for an artificial airway.

Rationale: Evaluation of the patient’s cardiopulmonary status assists in determining the need for an artificial airway.

• Assess pain according to institution standard.  Rationale: This assessment identifies the need for discomfort management.

Rationale: This assessment identifies the need for discomfort management.

• Assess patent nasal passageway. With finger pressure, occlude one nostril; feel for air movement under the open nostril. Patency also can be assessed with inspection of each naris with a flashlight.  Rationale: Assessment of patency promotes smooth, quick, unobstructed airway insertion.

Rationale: Assessment of patency promotes smooth, quick, unobstructed airway insertion.

• If a difficult insertion is anticipated (e.g., with nasal polyps, septal deviation), contact the practitioner for an order to apply a topical anesthetic to coat the nasal passageway.  Rationale: Topical anesthetics with a vasoconstrictor help shrink nasal mucosa and decrease the incidence of trauma and bleeding. Vasoconstrictor property acts on capillaries to decrease bleeding.

Rationale: Topical anesthetics with a vasoconstrictor help shrink nasal mucosa and decrease the incidence of trauma and bleeding. Vasoconstrictor property acts on capillaries to decrease bleeding.

Patient Preparation

• Ensure that the patient understands preprocedural teachings. Answer questions as they arise, and reinforce information as needed.  Rationale: This step evaluates and reinforces understanding of previously taught information.

Rationale: This step evaluates and reinforces understanding of previously taught information.

• Position the patient. Unless contraindicated, a supine or high Fowler’s position is acceptable.  Rationale: This positioning promotes patient and nurse comfort and provides easy access to the external nares.

Rationale: This positioning promotes patient and nurse comfort and provides easy access to the external nares.

References

![]() 1. American Association of Respiratory Care and Clinical Practice Guidelines, Nasotracheal suctioning, revision and update. 2004. American Association of Respiratory Care: Irving, TX.

1. American Association of Respiratory Care and Clinical Practice Guidelines, Nasotracheal suctioning, revision and update. 2004. American Association of Respiratory Care: Irving, TX.

2. Cummins, RO. Airway, airway adjuncts, oxygenation, and ventilation. In: In ACLS: principles and practice. Dallas: American Heart Association; 2006:145–146.

![]() 3. Eubanks, DH, Bone, RC, Comprehensive respiratory care. a learning system. Mosby, St Louis, 1990:491–495.

3. Eubanks, DH, Bone, RC, Comprehensive respiratory care. a learning system. Mosby, St Louis, 1990:491–495.

4. Pierce, LNB. Management of the mechanically ventilated patient, ed 2. St Louis: Saunders; 2007.

Roberts, K, Whalley, H, Bleetman, A, The nasopharyngeal airway. dispelling myths and establishing the facts. J Emerg Med 2005; 22:394–396.

St. John RE, Seckel, MA, Airway managementBurns SM, ed.. AACN protocols for practice. care of the mechanically ventilated patient. ed 2. 2007. Jones and Bartlett Publishers: Sudbury, MA.