CHAPTER 10. Foot care

Christine Skinner

Introduction 217

Foot health education 218

Assessing the diabetic foot 218

Treatment and management of foot lesions 226

Infection 228

Ulceration 230

Conclusion 241

References 242

The foot is a complex structure that is not only responsible for locomotion but is also designed to withstand the stresses of body weight while walking and standing. These stresses can result in microtrauma, which can lead to foot lesions. Foot problems are still the most common cause of hospital admissions for people with diabetes in the UK (Young et al 1994) and the length of stay is greater than for any other diabetic complication (Williams 1985). Foot disease remains one of the most common and devastating of diabetic complications, being responsible for a considerable amount of healthcare resource in the UK (Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) 55 2001). The estimated cost for ulceration and amputation in the UK in 2001 was £244 million (Shearer et al 2003). Diabetic foot disease often arises as a result of neuropathy, ischaemia, structural deformity or a combination of two or all of these factors.

Overall 20–40% of people with diabetes have neuropathy and 20–40% have peripheral vascular disease (Hutchinson et al 2000). Neuropathy and peripheral vascular disease develop as a result of poor blood glucose control and adverse risk factors such as smoking and dyslipidaemia (Hutchinson et al 2000). People with diabetes must also be aware of the influence of good glycaemic control, as hyperglycaemia can affect the microvascular status (UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) 1998).

Any minor trauma occurring in the foot can easily become infected and, if not managed correctly, can lead to the development of cellulitis, osteomyelitis and ultimately amputation. Of those people with diabetes, 5–7 % will develop a foot ulcer at some time in their life (SIGN 2001).

As complications associated with the diabetic foot have been described as a ‘major medical, social and economical problem’ of global proportions (Boulton & Vileikyte 2000) , it is imperative that all those involved in the care of the people with diabetes are familiar with aspects of care in the diabetic foot.

Foot complications can be associated with social deprivation, poor vision, disability, foot deformity and absence of professional foot care (Hutchinson et al 2000). All of these factors can influence the person’s ability to practise good foot care; however, there are two key aspects of foot care:

1. assessing the foot

2. treating foot lesions.

The management of the person should always have a multidisciplinary approach with close liaison between podiatrist, diabetologist, general practitioner, diabetes nurse specialist, the primary and community care nurse and orthotist.

Treatment by a podiatrist is free to all those with diabetes within the UK. The podiatrist should be involved in the care of the person with diabetes soon after diagnosis and thereafter as the individual is referred to them. It is recommended that people with diabetes only attend those podiatrists in the UK who are registered with the Health Professions Council.

FOOT HEALTH EDUCATION

Foot health education plays an important part in any successful management strategy. People who have had diabetes for many years may be unaware of the potential problems that can affect their feet. It must be remembered that whereas individuals with diabetes should be aware of these problems, it is important that they are not caused unnecessary alarm. It is essential, therefore, to gain the individual’s confidence and trust and to establish a rapport. In so doing, the practitioner will be able to gauge the levels of knowledge and understanding the person might have. Reassurance is essential to minimise the individual’s anxiety and re-enforcement of foot health education optimises self management.

ASSESSING THE DIABETIC FOOT

The multidisciplinary team must be aware of the guidelines published by National Collaborating Centre for Primary Care (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) 2004) and of the Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline 55 (SIGN 2001) in caring for the feet of a person with diabetes.

Primary care nurses might be involved in assessing the foot for diabetic complications as part of the annual screening visit or as part of their everyday care for these individuals. GPs might also be involved in assessing the feet at the screening clinic. It is important to record the outcome of findings to allow subsequent monitoring of the person’s feet.

Foot assessment requires some skills and experience in examining and interpretation. Examination of the foot involves assessment of soft tissues, structural deformities, vascular and neurological status and it is essential to assess and compare both lower limbs and feet.

SOFT TISSUE ASSESSMENT

This involves assessing both the skin and the nails.

Skin

When assessing the colour of the skin a comparison of the feet should be made. The colour and temperature of the skin are indicative of the blood flow through the foot. The skin of a foot with a good blood flow will be pale pink and warm to touch. If there is impaired blood flow the skin will be cold and pale. Cyanosis indicates a poor oxygen content and therefore poor blood supply. The appearance of a cold, hyperaemic (bright red) foot demonstrates ischaemia to the peripheral tissues and should be considered as a potential problem. The skin of an ischaemic foot is shiny, stretched, hairless and cool to touch.

The foot should be examined for the presence of soft tissue lesions such as callus, corns and any abrasions or indications of trauma. The interdigital spaces are often macerated and are a potential site for fungal infection and should not be overlooked.

People with autonomic neuropathy in their feet will have decreased sweating which results in dry, devitalised skin. The plantar aspect of the foot and the heel area are often affected, with the posterior aspect of the heel liable to fissuring providing a potential site for infection to develop.

Nails

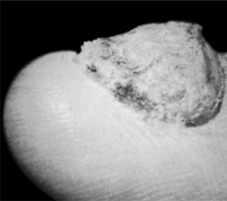

The nails can vary in appearance depending on the vascular state of the foot. In the ischaemic foot the nails may be thickened and slow growing. If they are infected by fungi they will appear thickened, discoloured and have a ‘musty’ smell (Figure 10.1). The nail grooves should also be examined to ensure that no callus or small spike of nail has penetrated the soft tissues of the groove, which can lead to an infected in-growing toenail (Figure 10.2). Nails that have been cut inappropriately can cause damage to the adjacent toe.

|

| Fig. 10.1The diabetic foot: nails thickened and discoloured by fungal infection |

|

| Fig. 10.2Infected in-growing toenail |

Structural deformities as a complication of diabetes act as a potential site for ulceration because the area is subjected to abnormal stresses. The combination of sensory neuropathy and increased pressure on the plantar aspect of the metatarsal heads may result in ulceration (Pham et al 2000).

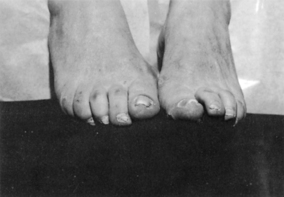

The toes are often in a clawed position as a result of motor neuropathy, which causes wasting of the small intrinsic muscles and allows the long flexors to have an unopposed action (Figure 10.3). The metatarsal heads therefore become much more prominent on the plantar surface and are subjected to greater stress during walking leading to the formation of hyperkeratosis. The dorsal aspect and tips of the toes are also liable to develop corns.

|

| Fig. 10.3Clawing of the toes as a result of motor neuropathy: long flexor muscles have unopposed action because small intrinsic muscles are wasted |

Structural deformities might also be present in the diabetic foot as a result of changes from Charcot neuropathic joints (Armstrong et al 1997). In the Charcot foot, pain perception and the ability to sense the position of the joints in the foot are severely impaired or lost, and muscles lose their ability to support the joint(s) properly. Loss of these motor and sensory nerve functions allow minor traumas such as sprains and stress fractures to go undetected and untreated leading to ligament laxity, joint dislocation, bone erosion, cartilage damage, and deformity of the foot. The bones most often affected are the metatarsals and the mid-foot (Figure 10.4).

|

| Fig. 10.4Charcot foot |

VASCULAR ASSESSMENT

The diabetic foot can be affected by both macrovascular and microvascular disease. Both have significant influences on the clinical appearance and the subsequent management of the foot. Symptoms of vascular insufficiency should be elicited from the individual. If the person complains of intermittent claudication, its severity can be assessed by determining how far the individual can walk before symptoms develop. It is also necessary to determine if the person suffers from pain when at rest, which is an indication of severe ischaemia.

It is essential to distinguish the pain of ischaemia from that of neuropathy, which often presents as a burning sensation.

Clinical assessment of the vascular state can be carried out routinely by performing a variety of physical tests. All members of the healthcare team, after suitable training, should be able perform these tests. To meet national guidelines, assessment must be carried out annually. People who are identified as ‘at risk’ following a vascular assessment should be referred for a more detailed peripheral arterial assessment (Stuart et al 2004, Watkins 2003).

PHYSICAL TESTS

Palpation of pulses

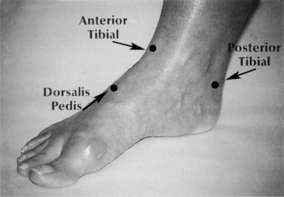

Peripheral circulation can be assessed by palpation of pedal pulses (Figure 10.5):

▪ The dorsalis pedis artery is a continuation of the anterior tibial artery. The pulse can be palpated on the dorsal aspect of the foot in the region of the intermediate cuneiform.

▪ The posterior tibial pulse can be palpated immediately behind the medial malleolus.

|

| Fig. 10.5Palpation of pedal pulses |

Confidence is essential in palpating pedal pulses, and such confidence is only acquired through practice. All members of the healthcare team need to be encouraged to develop this skill with normal, healthy people before progressing to people with known vascular complications. A hand-held Doppler can also be used.

It should be noted that arteriovenous shunts will develop due to autonomic neuropathy and, as a result, blood flow bypasses the capillary bed. Thus people might have bounding arterial pulses but have poor blood supply to the surrounding tissues. This is responsible for the venous engorgement often seen on the dorsum of the foot (Ward & Boulton 1987).

Temperature gradient

The temperature gradient can be assessed by gently running the back of the hand from below the knee distally to the toes. If there are any obvious changes intra- and interlimb, these should be noted.

Capillary refill

This is assessed by gently pressing the plantar aspect of the hallux until it blanches. Pressure is removed and the tissues allowed to reperfuse. Normal capillary refill should be 3 seconds.

Presence or absence of oedema

The presence of oedema can prevent the palpation of pedal pulses. If present, the affected sites should be noted.

Presence or absence of varicose veins

Varicose veins can lead to oedema of the ankle or dorsum of the foot and create a problem with socks and shoes. Any varicose veins should also be noted.

NEUROLOGICAL ASSESSMENT

Neuropathy is a major contributory factor in the development of ulceration in the diabetic foot (Thomson et al 1991). Neuropathy can affect sensory, motor or autonomic function. The most common diffuse neuropathy affecting people with diabetes is distal symmetric sensorimotor polyneuropathy (Boulton 2000). Some people with diabetes present with painful neuropathic symptoms; alternatively, this can develop over the following years. The person suffering from neuropathy can present with varying symptoms. He or she might complain of pain, which can be burning, sharp shooting or lancinating; paraesthesia; numbness with loss of pain; hot or cold sensations or irritation from bedclothes. Other unusual sensations might also be experienced and individuals might complain of the ‘feeling of cotton wool under their toes’ or ‘walking on hot sand’. If the person complains of pain it is important to distinguish the pain from that of ischaemia by assessing the quality of the pain and by examining the peripheral circulation.

If there is neuropathy present then a thorough structural assessment must be performed. This determines areas of pressure that might result in the development of callus and corns and eventually ulcers (Pham et al 2000).

Neuropathy might also result in damage to the soft tissue of the foot because, having lost sensation, the individual is unaware of trauma to the foot. Hence people are advised not to walk around on bare feet (Box 10.1 and Box 10.2). Prior to the neurological assessment being undertaken it is essential what is involved is explained to the person with diabetes. It is also useful to let the person experience the perceived sensation on an area where there is no sensory loss.

Box 10.1

Foot health education for the person with healthy feet

▪ Never walk barefoot

▪ Change hosiery daily

▪ Wash feet daily, dry carefully in between the toes

▪ Apply a cream to the soles and heels

▪ Inspect feet daily for corns/callosities/plantar warts/athlete’s foot

▪ If any of the above is present, they should only be treated by a registered podiatrist

▪ With the slightest abrasion or infection in your feet, contact your GP, community nurse, diabetic nurse specialist, diabetic consultant or podiatrist

▪ Never use proprietary treatments for callus or corns, as they contain acids

▪ Cut toenails straight across

▪ Buy new shoes from a shop that measures your feet and fits the shoes for you

▪ Never wear new shoes for a long period of time

▪ Stop smoking

▪ Only attend a podiatrist registered by the Health Professions Council

Box 10.2

Foot health education for the person with an ‘at risk’ foot

▪ All of Box 10.1 plus:

▪ Do not cut your own toenails

▪ Inspect feet daily for any open lesions, cracking, dryness, change in colour, swelling, corn, callus, blisters, warts or signs of infection

▪ Use a mirror to inspect the soles of your feet or ask someone to look for you

▪ Only use a hot water bottle to heat your bed: never place it next to your feet

▪ Never sit close to the fire or heater

▪ Check inside shoes for foreign objects

▪ Wear shoes with soft uppers, preferably lacing

▪ Never wear garters to hold up stockings or socks

This can be assessed using a piece of cotton wool. The person’s foot is gently touched with the cotton wool and sites identified where it can/cannot be appreciated. This commences distally and moves proximally, thereby moving from a potentially numb area to a normal area. It is easier to identify the boundary of sensory loss when moving from a numb area to an area of normal sensation. The person should have his or her eyes closed during this examination. Ensure that there is minimal variation in the pressure of application of the cotton wool. Note that the cotton wool should not be run across the tissues as people with paraesthesia can experience discomfort and pain.

Sharp and blunt sensation

A Neurotip can be used to identify if sharp and blunt sensation is present or absent. Again, the person’s eyes should be closed during this examination and the assessor should commence distally and work proximally.

Pressure

Pressure can effectively be assessed using a 10-g Semmes–Weinstein monofilament in predicting the risk of foot ulceration (Abbott et al 1998). Monofilaments are cheap and easy to use, making them an ideal screening tool. The sites tested are usually defined by local protocols but are generally agreed to be plantar aspects of the hallux, first, third and fifth metatarsal heads, heel and apices of the fourth and/or fifth digits; these are the most common sites for ulceration to develop. The monofilament is calibrated to buckle when a force of 10 g is exerted and if the person cannot feel the pressure the foot is considered to be insensate. The greater the number of negative responses identified, the greater the risk (Baker et al 2005).

It is important to ensure that any areas of hyperkeratosis are removed before carrying out this test (Figure 10.6).

|

| Fig. 10.6Monofilament |

Vibration

Vibration perception can be assessed using a standard 128-Hz tuning fork or a Reydell Sieffer tuning fork with a graduated scale, which will give a recordable measurement. Sites that should be assessed are the ankle, first metatarso-phalangeal joint and the plantar of the hallux. The person should have his or her eyes closed for this assessment. He or she should experience a buzzing sensation and indicate when this can no longer be felt. A neurothesiometer can also be used and will give a quantifiable reading but this is an expensive piece of equipment not available to many practitioners.

Autonomic neuropathy

Individuals with autonomic neuropathy usually have dry and flaky skin on their feet, and sometimes fissuring in the heel area. This can be a potential site for bacterial infection, which might result in ulceration.

Other tests, which require specialised equipment, can be used to enhance the examination of the diabetic foot. These are usually carried out by the podiatrist. The purpose of assessing the diabetic foot under the various parameters outlined above is to determine the foot which is ‘at risk’ and undertake a management strategy according to SIGN (2001).

The ‘at risk’ foot may, therefore, be defined as the foot which has any one of the clinical signs detailed inbox 10.3

Box 10.3

The ‘at risk’ foot has any one of these clinical signs

▪ Ischaemia

▪ Numbness

▪ Structural deformities

▪ Callus and/or corn

▪ Absence of pedal pulses

▪ A capillary refill time in excess of 3 seconds

▪ Limb pain and/or paraesthesia

▪ Intermittent claudication

▪ History of foot ulcers

▪ Loss of sensation of light touch, sharp and blunt touch

Further detailed instructions in foot health care (see Box 10.2) should be given if the person is assessed as having an ‘at risk’ foot. Patient education in the prevention of foot problems is the first line of defence. The individual’s ability to understand the importance of foot health education should be assessed. The person should also receive regular podiatry care and be made aware of a system for seeking immediate medical attention if a foot problem arises. All healthcare professionals must continually reinforce appropriate foot health education.

TREATMENT AND MANAGEMENT OF FOOT LESIONS

People can present with a wide range of foot problems. Some people require only routine nail cutting and simple advice on foot care (see Box 10.1). Others will have nail problems, callus, corns or even ulceration and will require more intensive care and education (see Box 10.2).

Toenail cutting in people with diabetes is a matter of great debate, and whether individuals receive this care routinely very often depends on local health board protocols. The task can be one that a nurse, carer or other practitioner can undertake if they have been taught appropriately and deemed to be competent. Many people with healthy feet can undertake safe practice in nail care themselves. However, those ‘at risk’ must attend a podiatrist regularly for nail routine.

Nails should be cut straight across without cutting down into the corners. Check that there are no ragged edges or sharp corners, which could irritate either the soft tissues of the sulcus of the nail or the adjacent toe. Small spurs of nail may penetrate the soft tissues of the sulcus and an in-growing toenail can develop (see Figure 10.2).

If the nail is excessively curved, a light pack of sterile cotton wool or chamois can be used under the lateral edge of the nail to prevent it irritating the soft tissues of the sulcus (Figure 10.7).

|

| Fig. 10.7Nail reduction: sterile cotton wool used under lateral edge of the nail to prevent irritation |

The person should be referred to a podiatrist if the nails are thickened as a result of trauma or peripheral vascular disease.

CALLUS AND CORNS

People with diabetes are advised never to treat callus or corns with proprietary medication. ‘Corn pads’ contain salicylic acid, which can cause chemical trauma to the foot. This is undesirable, especially if the person has neuropathy. These lesions should only be treated by a registered podiatrist.

MECHANICAL THERAPY

In the presence of callus or corns, the podiatrist will reduce these to minimise the pressure being exerted onto the area, and provide mechanical therapy to either redistribute abnormal pressure or cushion the area.

Ill-fitting footwear can contribute to foot problems such as ulceration in the person with diabetes (Thomson et al 1991). Footwear should be adequate to accommodate the shape of the foot. People with healthy feet and no lesions can be advised to purchase shoes from a reputable retailer where their feet will be measured and shoes fitted prior to purchase.

Footwear should also be appropriate to the lifestyle of the individual. Good-quality training shoes are ideal for the person who is involved in walking a great deal, as this type of footwear has a deep toe box and thick cushioned sole.

Women with diabetes should be advised on the limited use of court shoes that constrict the toes and have no retaining strap. The height of the heel results in the weight being concentrated onto the forefoot.

People with foot deformities such as hallux valgus, hammer or claw toes require shoes that are wider and deeper than normal. These can be provided from a number of specialist footwear suppliers and are available from the NHS (Figure 10.8). People with gross foot deformities will require custom-made shoes, which can be authorised by their GP, orthopaedic surgeon or diabetes physician. Some people will require insoles to alleviate abnormal pressures in the foot. Again, the podiatrist can facilitate and supervise these.

|

| Fig. 10.8Footwear for people with foot deformities |

INFECTION

People whose glycaemic control is poor are more susceptible to infections and, if ulceration is present, are likely to have delayed healing.

FUNGAL INFECTION

The most common site on the foot for fungal infection is the interdigital spaces. The skin in the affected area may be white, macerated and peeling. The person will complain of itching and there is the danger of scratching the area and spreading the infection on to the dorsum of the foot. Treatment is usually easy when the fungus responsible has been identified and antifungal agents commenced. However, as with non-diabetic people, fungal infections tend to recur.

When dealing with this type of infection it is important to stress to the person the need for good foot hygiene and that they avoid scratching as this may break the skin allowing a secondary bacterial infection to develop. The person should be referred to their GP for consideration of antibiotic therapy should this occur.

BACTERIAL INFECTION

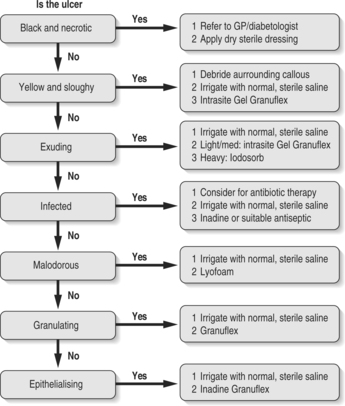

Secondary infection can be a common problem following tissue breakdown in the diabetic foot. The most common organisms responsible are staphylococci, beta-haemolytic streptococci, aerobic Gram-negative bacilli and anaerobic bacteria (Edmonds et al 1986). When the person presents with a discharging lesion, a swab of the pus should be taken and sent to bacteriology. The individual should be referred immediately to their GP for consideration of antibiotic therapy. Localised treatment involves cleansing the wound with sterile, tepid, saline and dressing with an appropriate dressing (Figure 10.9) as well as providing protection and pressure relief to the area. The area is monitored for signs of cellulitis and lymphangitis. X-ray of the foot is important to exclude gas gangrene or osteomyelitis.

|

| Fig. 10.9Diabetic foot ulcer protocol |

Close liaison with all those involved in the treatment of the person with a bacterial infection should enable a satisfactory outcome. This is important as infection in the foot, usually as a result of ulceration, still remains one of the major final pathways to lower limb amputations in people with diabetes (Apelqvist & Larsson 2000).

ULCERATION

Diabetic foot ulceration is a major management problem and prevention of the occurrence and recurrence of such lesions is challenging for all members of the multidisciplinary team.

Abnormal foot pressures are a contributory factor in the development of ulceration in the diabetic foot (Masson et al 1989). Clinical evaluation identifies structural abnormalities creating areas of abnormally high pressure, which might result in the development of corn and callus. There is an increased risk of ulceration developing if callus is not reduced, if pressure persists or if the foot has diminished sensation.

The most common sites are the plantar aspect of the metatarsal heads and the dorsum of the toes if they are clawed. This clinical evaluation is particularly important if there is neuropathy or vascular disease present (see Box 10.3).

Ulceration can also develop in the diabetic foot as a result of constant pressure, e.g. poorly fitting shoes or a foreign object in the shoe. A person affected by peripheral neuropathy causing loss of sensation will allow the pressure to continue for many hours, unaware of tissue damage.

The clinical appearance of the ulcerated area must be recorded to allow objective assessment of healing, by serial measurement of ulcer size. Using a ruler, trace the area and surrounding tissue. Alternatively a photograph of the area and surrounding tissue is more desirable. The person should be referred to the diabetes physician for guidance on antibiotic therapy if an ulcer is present.

RELIEVING PRESSURE ON AN ULCER

To assist in the healing process, the wound must not be subjected to any unnecessary trauma or excessive, abnormal weight-bearing stresses. Complete bed rest is often desirable but not always practical or acceptable to the individual concerned. Therefore, alternative regimes should be considered. The podiatrist can advise on various techniques which can play an important role in this aspect of management of diabetic ulceration.

There are various examples of boots available on the market that can provide pressure relief at the ulcerated site either in the forefoot or heel area (Figure 10.10) but still allow easy access to the wound for dressing and assessment. These boots are usually acceptable to the individual and encourage compliance. An alternative is a total contact cast that relieves pressure on the affected area but still allows the person to remain mobile (Pollard & Le Quesne 1983). Another alternative is an aircast boot (Figure 10.11), although some people find these cumbersome. They are contraindicated if severe infection is present or if there is peripheral ischaemia.

|

| Fig. 10.10The IPOS Boot |

|

| Fig. 10.11The total contact cast |

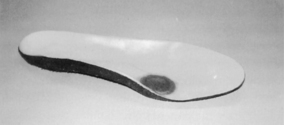

When the ulcer has healed it is important to reduce the risk of recurrence at the site and the person should be provided with either a simple insole or a moulded insole (Figure 10.12).

|

| Fig. 10.12A moulded insole to prevent excessive pressure on a foot ulcer |

People must be advised on suitable footwear, which should be sufficiently wide and deep to accommodate any foot deformity. It should also have a retaining medium, such as laces or a ‘T’ bar, and no stitching or seams on the upper, which may cause unnecessary trauma.

Neuropathic ulcers

A remarkably accurate description of a neuropathic ulcer was first given as long ago as the early nineteenth century (Mott 1818):

A round ulcer in the sole of the foot surrounded by a remarkably rough hardening of thick cuticle, characterised by a great degree of insensitivity.

Neuropathic ulcers characteristically develop on areas of abnormal pressure, such as the plantar aspect of the metatarsal heads. Ulceration can also develop on the medial side of the first metatarsal or lateral side of the fifth metatarsal as a result of pressure from shoes.

The ulcer often has a ‘punched out’ appearance and consists of a central cavity, usually much larger than the opening into it, surrounded by a hard thick plaque of hyperkeratotic tissue. The ulcer may have slough present on the base or have an infected pus discharge with or without surrounding cellulitis. It may be necessary to X-ray the foot to exclude for osteomyelitis.

Characteristically, the ulcer is painless; often, a moist discharge on hosiery alerts the person to the lesion. The foot is often warm, pink and dry with palpable pedal pulses. The neuropathic foot is also at risk of ulceration from direct trauma, e.g. standing on sharp objects; thermal trauma, e.g. hot water bottles; chemical trauma, e.g. ‘corn pads’ that contain salicylic acid. The latter being the reason why the person with diabetes is advised never to use these products.

Mary is a 64-year-old woman who has had type 2 diabetes for 10 years. She has been meticulous about her diet and blood glucose control since diagnosis. She attends the diabetic clinic for annual review and regularly attends the podiatrist to have her nails cut, having no other foot problems. On a routine visit to the clinic she complains of numbness in her right foot.

On closer inspection of her foot there is a small ulcer under the second metatarsal head and evidence of leakage on her tights. Mary is adamant that she never walks barefooted and only ever wears the lacing shoe she had with her. The shoe is examined and reveals a drawing pin sticking through the sole of her right shoe. It was unclear how long it had been there as Mary stated that she had not checked the inside of her shoe for several days.

From the development of this lesion and the history it was obvious that Mary had peripheral neuropathy. Tests were carried out by the podiatrist to determine its extent. As on all visits, Mary’s circulation was assessed by checking pedal pulses, colour, capillary refill and temperature gradient. These latter tests were satisfactory. The findings of the assessment were recorded.

With Mary’s permission, the podiatrist proceeded to dress the ulcer. The foot was cleansed with antiseptic solution and the ulcer was debrided using a scalpel. All dressings should be considered as sterile dressings, whether done in a clinic setting or in the person’s home. An assessment of the ulcer was made regarding size and condition of the base. As there was a discharge and surrounding inflammation, a swab was taken of the exudate and sent for bacterial culture and sensitivity. As the wound was showing signs of infection and there was slough at the base, an appropriate dressing was selected (see Figure 10.9). The ulcer was irrigated with tepid, sterile, normal saline and surrounding tissues gently dried using sterile gauze. The area was dressed with an appropriate dressing and a deflective felt pad applied.

The drawing pin was removed from Mary’s shoe and her GP was contacted to inform him of the situation and to consider antibiotic therapy. A further appointment was made for Mary to attend the podiatrist the next day and she was advised to elevate her foot meantime. To minimise weight bearing at the site, Mary was given an Ipos shoe (see Fig 10.10).

As Mary had now developed peripheral neuropathy she required further foot health education, which could be provided by the podiatrist.

On the subsequent visit the dressing to Mary’s ulcer was removed and the area assessed. There was evidence of discharge. The area was irrigated with sterile, normal saline. The base of the ulcer was cleaner but there was still evidence of slough. A further dressing was applied and Mary was again asked to return the next day. Thereafter, Mary was closely monitored until the ulcer healed. Her diabetes physician was kept informed of the developments in her condition.

The long-term management of Mary would be to re-educate her in foot health and continue to see her at the clinic at regular intervals.

Ischaemic ulcers can develop on the foot of a person with diabetes suffering from peripheral vascular disease. These ulcers can develop on the dorsum or apices of the toes, or on the outer borders of the foot. This is particularly so if hallux valgus is present, the forefoot is broad and the person wears tight-fitting shoes.

Ischaemic necrosis of the tissue can develop as a result of pressure of the footwear obliterating the capillary flow to the area, or as a result of a blockage in the vessel to the area.

The area is usually dry and has a definite line of demarcation which is characteristic of gangrene. If the blockage has been acute, oedema and infection will occur giving a wet gangrene. The person will complain of severe pain and there is usually a history of intermittent claudication and rest pain.

Bob is a 70-year-old man who has had type 1 diabetes for 45 years. His diabetes is well controlled. He is retired and leads a relatively inactive life and smoked 25 cigarettes a day until 3 years ago. He regularly attends the podiatrist for the reduction of a corn on his left foot and to have his toenails cut. Bob is aware of the importance of these visits as his circulation has deteriorated over the past 10 years. There has been a history of intermittent claudication, with his walking distance decreasing, and rest pain. Previous assessment by the vascular surgeon showed a blockage at the popliteal fossa. Bob presents at the clinic complaining of a small discoloured area at the tip of his left second toe and another on his ‘bunion’, which had appeared when he was on holiday. On examination of his feet, they are pale and cold to touch.

Bob’s second toe of the left foot is dusky purple at the metatarsal phalangeal joint and gets progressively darker towards the tip, where it is black. An area of necrosis is also present on the medial aspect of his left 1st metatarsal phalangeal joint. Both areas are dry and show no sign of any exudate. Bob complains of severe pain, which prevents him from sleeping at night and also makes him feel nauseous.

With Bob’s permission, the area is swabbed with sterile, normal saline and a dry, sterile dressing applied. The podiatrist, in consultation with the diabetes physician, agrees to refer Bob to the vascular surgeon for investigation of his main limb arteries to ascertain if any surgical intervention is feasible.

Bob is given an Ipos shoe to relieve any pressure on the area and prescribed pain relief. His GP is informed of the development in his condition. Twice-weekly visits were arranged for Bob to allow the podiatrist to monitor his condition. After 2 weeks his foot was showing signs of deterioration: the pain had increased and his quality of life had deteriorated. Multiprofessional review indicated that no reconstructive surgery could be carried out. Unfortunately, Bob needed a below-knee amputation.

There is great variation and debate in the treatment of both ischaemic and neuropathic ulceration with regard to topical dressing and antibiotic therapy. Treatment therefore depends on the local expertise and protocols on the use of the currently available dressings. Consultation with tissue viability nurses is useful when dealing with diabetic ulceration.

Assessment of the wound for dressing

A greater understanding of the science of wound management and the importance of providing the best environment for wound healing has led to a significant improvement in the range of treatments available. The selection process of the dressing is dependent on the assessment of the wound initially. On examination of the wound it is essential to determine which features are present (Box 10.4).

Box 10.4

Features that can be present when assessing the wound for a dressing

▪ Necrosis

▪ Epithelialisation

▪ Infection

▪ Depth

▪ Slough

▪ Exudate

▪ Granulation

▪ Malodour

The wound might have more than one of these features. The dressing of choice should address the most prominent or serious factor.

If infection is suspected, a swab must be sent for bacterial culture and antibiotic sensitivity with the person commenced on antibiotic therapy. In people with diabetes, such antibiotic therapy is often of a much longer duration than in the normal population and cover for periods of several weeks is not unusual.

Wound cleansing is essential before applying any dressing and tepid, sterile, normal saline is the one of choice. The use of chlorinated solutions such as Milton or Eusol are no longer recommended for cleansing wounds as they have been found to be toxic to tissues and cells involved in the healing process. They can be irritants to surrounding healthy tissue and have been known to cause bleeding. Hydrogen peroxide is no longer recommended for irrigation of wounds as it can cause irritation to the tissues, stinging and a burning sensation (Leaper 1986). However, a number of wound dressings are currently available that have been used with a degree of success depending on the stage of ulceration.

The use of more traditional dressings, such as gauze with antiseptics, is less favoured because fibres from the gauze can remain on the surface, acting as an irritant and delaying healing. Discharge from the wound can cause adherence of the dressing to the wound surface. Removal of the dressing can further traumatise the healing wound, damaging the granulating tissue. Care should also be taken when dealing with thin, friable skin because the repeated application and removal of adhesive dressings and tapes can cause tissue damage (Dykes et al 2001).

Interactive dressings

Interactive dressings provide the optimum conditions for wound healing by maintaining a moist environment at the wound surface. They also allow gaseous exchange of oxygen, carbon dioxide and water vapour but are impermeable to the passage of bacteria.

There has been a great deal of controversy as to the use of totally occlusive dressings, preventing the passage of oxygen to the wound. Some research has found that there is rapid formation of capillaries and granulation tissue with an anaerobic environment and as a result of the occlusion, prostaglandin synthesis is inhibited and therefore pain is reduced (Morgan 1990a).

When dealing with diabetic ulceration, however, a great deal of consideration must be given before selecting or applying an occlusive dressing. This should not be used if microvascular disease is present or if anaerobic bacteria infect the wound (Morgan 1990b).

Thermal insulation also aids in the healing process, so dressings should provide insulation and the person should be encouraged to choose suitable footwear.

Environmental dressings

These dressings tend to be more expensive than the traditional dressings. They can be cost-effective, however, because they may be left in situ for several days if the wound is clean. This reduces the need to redress a foot on a daily basis, thus decreasing the costs of both materials and time for the podiatrist or primary care team.

There are many types of environmental dressings from which to select. The groups are listed inbox 10.5

Box 10.5

Classification of environmental

▪ Hydrogel

▪ Hydrofibre

▪ Hydrocellular foam

▪ Alginate

▪ Hydrocolloid

▪ Semi-permeable films

▪ Silver antimicrobial

It is essential that the appropriate dressing is chosen depending on the characteristics of the wound. Each group will be considered in turn to allow the reader the opportunity to compare and contrast the advantages and disadvantages of each.

These are cheap, permeable to water vapour and gases and act as a barrier to external contamination. They can be left in situ for up to 7 days. However, there is sometimes a problem with sizing for smaller wounds and, because they are non-absorbent, they cannot be used if there is a heavy exudate. Care should be exercised with thin, fragile but intact skin. Semi-permeable polymeric films are recommended for shallow ulcers with little exudate.

▪ Example: Dermafilm, Dermoclude, Ensure-it, Omiderm, Opsite, Polyskin, Tegaderm.

▪ Features: sterile, thin, transparent, hypoallergenic, adhesive film.

▪ Uses: shallow ulcers with little exudate.

▪ Contraindications: heavily exuding wounds, as they may trap the exudate.

▪ Requirements: top dressing to protect and insulate the wound.

Hydrocolloids

These dressings are adhesive, flexible and occlusive. They consist of two layers: an outer protective waterproof layer is bonded to an inner layer of hydrocolloid particles and a hydrophobic polymer.

The inner layer of these dressings absorbs the exudate, swells, liquefies and forms a soft moist yellow gel over the wound surface. Note: it is important that this feature is not confused with slough. When removed, the gel separates causing no trauma to the tissues. However, care should be taken when removing the dressings because they can damage fragile skin. They encourage formation of granulation tissue but might be malodorous. They are easy to use and allow rapid debridement and, as they are waterproof, allow the person to bathe while wearing the dressing. Hydrocolloids should not be used where anaerobic activity is suspected due to the occlusive properties of the dressing as anaerobic activity may be encouraged.

▪ Examples: Granuflex, Duoderm, Tegasorb.

▪ Uses: wound requiring debridement of necrotic tissue; moderate exudate.

▪ Contraindications: anaerobic bacteria are present in the wound.

Hydrogels

This dressing consists of a pale yellow transparent gel containing starch copolymer. It is usually available in a small plastic dispenser and is used where hydration of necrotic slough within the wound is required. Dressings must be changed daily if slough is present but they can be left for 3 days in clean wounds. The gel is easy to apply and can reduce pain. However, it could be considered wasteful as the remainder of the dispenser must be discarded. If the gel is difficult to remove, a soak of sterile, tepid saline solution should be used. Care should also be taken not to macerate the edges of the wound by overloading it with the gel.

▪ Examples: Granuflex, Duoderm, Tegasorb.

▪ Uses: wound requiring debridement of necrotic tissue; moderate exudate.

▪ Contraindications: anaerobic bacteria are present in the wound.

Hydrogels

This dressing consists of a pale yellow transparent gel containing starch copolymer. It is usually available in a small plastic dispenser and is used where hydration of necrotic slough within the wound is required. Dressings must be changed daily if slough is present but they can be left for 3 days in clean wounds. The gel is easy to apply and can reduce pain. However, it could be considered wasteful as the remainder of the dispenser must be discarded. If the gel is difficult to remove, a soak of sterile, tepid saline solution should be used. Care should also be taken not to macerate the edges of the wound by overloading it with the gel.

▪ Examples: Intrasite Gel, Purilon.

▪ Indications: sloughy wounds (deep or shallow), granulating wounds, sinuses.

▪ Contraindications: do not use with iodine or povidone iodine preparations.

These dressings are hydrophilic and absorb wound exudate, carrying debris and bacteria away from the wound surface. Some are in granule or bead form and are difficult to apply to the foot. These dressings should never be allowed to dry out and must be changed daily. The area should always be cleansed thoroughly with tepid, sterile, normal saline solution.

▪ Examples: Debrisan, Iodosorb.

▪ Uses: sloughy, infected, exudating wounds.

Alginates

These products are manufactured from brown seaweed and are available as flat pads, packing or ribbon. These dressings are biodegradable, cheap and easy to apply. They absorb the wound exudate and form a gel that moulds to the shape of the cavity. Dressings should be changed daily if heavy exudate is present, or every 3 days if low exudate. To facilitate the removal of the dressing, sterile, tepid, saline solution must be used.

▪ Examples: Kaltostat, Kaltocarb, Algosteril.

▪ Indications: use on exuding wounds.

▪ Contraindications: dry or necrotic wounds.

Polyurethane foams

Polyurethane foams are manufactured as flat sheets with an outer layer preventing leakage of exudate and an inner hydrophilic surface. Some contain a carbon layer, which controls offensive odours. These dressings should be changed daily depending on the exudate. As the wound heals and discharge lessens, they can be left in place for up to 7 days. They have high thermal properties. Dressing size can be a problem for small areas.

▪ Examples: Lyofoam, Lyofoam C.

▪ Indications: medium to heavy exuding wounds; malodorous wounds.

▪ Contraindications: patients sensitive to nylon.

Before selecting a specific dressing, consideration must be given to both the stage of the wound to be dressed and the various properties of different dressings available. Primary care nurses who might be responsible for undertaking the dressings should not alter the prescribed dressing without consulting the person who made the prescription.

Hydrofibre

These dressings maintain a moist environment and are usually used in conjunction with a secondary dressing such as a foam. They have excellent properties of managing exudates.

▪ Examples: Aquacel.

▪ Indications: medium to heavy exuding wounds.

These maintain a moist environment and are ideal if exudates are present. They come in many different presentations, such as adhesive or non-adhesive; therefore, careful assessment of the wound and surrounding tissue is essential prior to use.

▪ Examples: Allevyn, Biatain.

▪ Indications: medium to heavy exuding wounds.

▪ Contraindications: Adhesive dressing on thin friable skin.

Silver antimicrobial dressings

The use of silver as an antimicrobial has been known since the ancient Egyptians added it to drinking water to prevent water-borne infections (Lansdown 2004).

Silver antimicrobial dressings should be used in critically colonised wounds whereby the wound is not infected but the person’s ability to heal is impaired or when the wounds are infected with a purulent discharge and malodour.

▪ Examples: Contreet, Acticoat, Aquacel Ag.

▪ Indications: critically colonised wounds; infected wounds.

▪ Contraindications: people who are sensitive to silver.

Maggot therapy

Debridement of an ulcer is an important factor that must be addressed to achieve wound healing. Debridement can be achieved by skilful scalpel reduction by the podiatrist or surgically by the vascular surgeon. However, the presence of slough in a diabetic foot ulcer is a common complication. It will deter healing and, often, successful debridement cannot be achieved. Larvae, or maggot, therapy is an invaluable method of removing slough from many types of wound (Evans 2002) and has also been proven to be an effective method of debridement (Courtney et al 2000).

Maggot therapy is relatively common in diabetic foot ulceration as it has been shown to reduce the number of resistant organisms (Thomas et al 1999) and has also proved to be cost effective (Wayman et al 2000). Its use has also been shown to be effective in non-healing ulcers (Sherman 2003).

The larvae secrete enzymes, collagenases, which act on slough present in the wound (Hobson 1931). They also have an effect on the bacteria present in the wound by changing the pH from acid to alkali.

Compliance is a problem with larval therapy. Individuals can perceive the larvae as ‘something nasty, creeping and crawling in the wound’. The healthcare professional should reassure the recipient of the benefits and give an explanation of the specific action of the larvae, which should help overcome their concerns and dispel their fear and anxiety. Larvae are very efficient at cleaning the wound bed and stimulating the formation of granulation tissue, both of which are essential for successful healing. The technique for their application is important and must be practised by the nurse/podiatrist to ensure confidence in their use.

Many factors influence the healing rate of an ulcer. It is, therefore, the role of the multidisciplinary team to liaise to achieve the best outcome for the individual concerned. Factors that might be present and should be considered are:

▪ ischaemia

▪ pressure/friction

▪ slough

▪ infection

▪ barriers to self management

▪ pain

▪ nutritional status.

The management of the person with a diabetic foot can be variable, depending on the presenting clinical picture. All involved in the care should be vigilant to address the following risk factors for development of foot ulceration:

▪ Poor eyesight: the individual is unable to cut his or her own toenails or to inspect the feet daily.

▪ Age: elderly people are less mobile and therefore less able to deal with normal foot hygiene.

▪ Previous foot ulceration: leaving an area of high pressure or fragile skin.

▪ Smoking: responsible for vascular disease and resultant effect on blood supply to the foot. There is a danger of the person burning his or her skin with a cigarette or lighter but, because of neuropathy, being unaware that this has happened.

▪ Neuropathy.

▪ Peripheral vascular disease.

▪ Structural deformity of the foot.

▪ Prevailing glycaemic control.

The multidisciplinary team in both primary and secondary care must work together to prevent foot problems and to treat early any detected abnormalities. The ultimate goal is to keep ‘these feet…made for walking, walk for life’.

Despite all efforts by those involved in diabetes care, some people do require amputation of a lower limb. It has been estimated that those with diabetes are 15 times more likely to need amputation than people without the condition and approximately 10% will have undergone some form of amputation, ranging from a single digit to a major above-knee amputation. People who have had a digital or mid-foot amputation will require close monitoring because the dynamics of the foot will have altered. If there has been either a below- or above-knee amputation, the contralateral limb is at greater risk of trauma due to the alteration in gait.

The findings from the neurological assessment carried out on the right foot and Helga’s below-knee amputation on the left leg put her in the ‘at risk’ category. Consultation with the orthotist to prescribe appropriate footwear is necessary and the podiatrist provided a casted orthosis to support and cushion her right foot.

Daily observation by Helga is essential to determine any colour change or the development of an open wound is essential. The podiatrist monitored Helga’s right foot on a monthly basis and carried out any treatment, such as nail cutting, as necessary. At these visits, the podiatrist assessed and recorded the findings from the vascular and neurological assessment. The main aim in Helga’s care is to maintain tissue integrity, prevent ulceration and ultimately prevent amputation. Obviously this has also had a major impact on her active lifestyle and she will require counselling to adapt to these changes in her life (see Chapter 3).

CONCLUSION

Caring for the feet of the person with diabetes is a challenge to the individual concerned and all members of the healthcare team. Education plays a crucial role in the prevention of foot problems and this must be reinforced consistently by all members of the healthcare team.

Daily assessment of the feet by the person or carer is the first point of prevention. At the slightest irregularity, no matter how trivial it might seem, the person should consult his or her GP, primary care nurse, diabetic nurse specialist or podiatrist. Good communications between the multidisciplinary team will facilitate speedy and appropriate management of the diabetic foot.

…to raise an awareness in the population and among health care professionals of present opportunities and the future needs for prevention of the complications of diabetes and of diabetes itself, and to reduce the number of amputations for diabetic gangrene in Europe by 50%. (Diabetes Care and Research in Europe 1990)

A multidisciplinary approach will facilitate the achievement of this goal.

REFERENCES

CA Abbott, L Vileikyte, S Williamson, et al., Multicentre study of the incidence of and predictive risk factors for diabetic neuropathic foot ulceration, Diabetes Care 21 (7) (1998) 1071–1075.

J Apelqvist, J Larsson, What is the most effective way to reduce incidence of amputation in the diabetic foot? Diabetes and Metabolism 1 (2000) 75–83.

DG Armstrong, WF Todd, LA Lavery, et al., The natural history of acute Charcot’s arthropathy in a diabetic foot speciality clinic, Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association 87 (1997) 272–278.

N Baker, S Murali-Krishnan, G Rayman, A user’s guide to foot screening. Part 1: peripheral neuropathy, Diabetic Foot 8 (1) (2005) 28–37.

A Boulton, L Vileikyte, The diabetic foot: the scope of the problem, Journal of Family Practice 49 (2000) S3–S8.

AJ Boulton, The pathway to ulceration; aetiopathogenesis, In: (Editors: AJ Boulton, H Connor, PR Cavanagh) The foot in diabetes 3rd edn. (2000) John Wiley, Chichester.

M Courtney, J Church, T Ryan, Larvae therapy in wound management, Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 93 (Feb) (2000) 72–74.

Diabetes Care and Research in Europe, The Saint Vincent Declaration, Diabetic Medicine 7 (4) (1990) 360.

PJ Dykes, R Heggie, SA Hill, Effects of adhesive dressings on the stratum corneum of the skin, Journal of Wound Care 10 (2001) 2.

ME Edmonds, MP Blundell, HE Morris, et al., Improved survival of the diabetic foot: the role of the specialised foot clinic, Quarterly Journal of Medicine 60 (1986) 763–771.

P Evans, Larvae therapy and venous leg ulcers: reducing the ‘yuk factor’, Journal of Wound Care 11 (10) (2002) 407–408.

R Hobson, On an enzyme from blow-fly larvae (Lucillia sericata) which digests collagen in alkaline solution, Biochemistry 25 (1931) 1458–1463.

A Hutchinson, A McIntosh, G Feder, et al., Clinical guidelines for type 2 diabetes: Prevention and management of foot problems. (2000) Royal College of General Practitioners, London .

A Lansdown, A review of the use of silver in wound care: facts of fallacies? British Journal of Nursing 13 (6 suppl) (2004) 6–17.

D Leaper, Antiseptics and their effect on healing tissue, Nursing Times 82 (22) (1986) 45–47.

EA Masson, EM Hay, I Stockley, et al., Abnormal foot pressures alone may not cause ulceration, Diabetic Medicine 6 (1989) 426–428 .

D Morgan, Development of a wound management policy: part 1, Pharmaceutical Journal (1990 March) 295–297.

D Morgan, Development of a wound management policy: part 2, Pharmaceutical Journal (1990 March) 358–359.

VA Mott, A cause of circular callous ulcer in the bottom of the foot, Medical Surgical Register New York 1 (1818) 129.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), Type 2 diabetes: prevention and management of foot problems. (2004) NICE, London .

H Pham, DG Armstrong, C Harvey, et al., Screening techniques to identify people at high risk for diabetic foot ulceration: a prospective multicentre trial, Diabetes Care 23 (2000) 606–611.

JP Pollard, LP Le Quense, Method of healing diabetic forefoot ulcers, British Medical Journal 286 (1983) 436–437.

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines (SIGN), No. 55: management of diabetes. (2001) SIGN, Edinburgh .

A Shearer, P Scuffham, A Gordois, A Oglesby, Predicted costs and outcomes of reduced vibration detection in the UK, Diabetic Foot 6 (1) (2003) 30–37.

RA Sherman, Maggot therapy for treating diabetic foot ulcers unresponsive to conventional therapy, Diabetes Care 26 (2) (2003) 446–451.

L Stuart, P Wiles, P Chadwick, P Smith, Improving peripheral arterial assessment of people with diabetes, Diabetic Foot 7 (4) (2004) 183–186.

S Thomas, A Andrews, NP Hay, S Bourgoise, The anti-microbial activity of maggot secretions: results of a preliminary study, Journal of Tissue Viability 9 (4) (1999) 127–132.

FJ Thomson, A Veves, H Ashe, et al., A team approach to diabetic foot care — the Manchester experience, The Foot 1 (2) (1991) 75–82.

United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS), Intensive blood glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes, Lancet 352 (1998) 837–853.

JD Ward, AJM Boulton, Peripheral vascular abnormalities and diabetic neuropathy, In: (Editor: PJ Dyck, et al.) Diabetic neuropathy (1987) Saunders, Philadelphia.

PJ Watkins, In: The diabetic foot (2003) ABC of diabetes BMJ Publishing Group, London, pp. 59–64.

J Wayman, V Nirojogi, A Walker, et al., The cost effectiveness of larval therapy in venous ulcers, Journal of Tissue Viability 10 (3) (2000) 91–94.

DRR Williams, Hospital admissions of diabetic patients: information from hospital activity analysis, Diabetic Medicine 2 (1985) 27–32.

MJ Young, JL Breddy, A Veves, AJ Boulton, The prediction of diabetic neuropathic foot ulceration using vibration perception thresholds, A prospective study Diabetes Care 17 (1994) 557–560.