CHAPTER 10. Euthanasia, assisted suicide and the nursing profession

L earning objectives

▪ Define and differentiate between the terms ‘euthanasia’, ‘assisted suicide’ and ‘mercy killing’.

▪ Explain why dictionary definitions of euthanasia can be misleading when considering the ethics of euthanasia and assisted suicide.

▪ Outline five conditions that must be satisfied in order for an act to count as an instance of euthanasia.

▪ Differentiate between six types of euthanasia commonly discussed in the bioethics literature.

▪ Discuss critically at least:

• six arguments commonly raised in support of euthanasia and assisted suicide

• seven arguments commonly raised against euthanasia and assisted suicide.

▪ Discuss critically the possible impact of climate change on the euthanasia debate.

▪ Discuss critically the nature and moral implications of ‘psychiatric euthanasia’.

▪ Examine critically the killing/letting die distinction.

▪ Discuss critically the issue of terminal sedation associated with the withholding of artificial hydration and nutrition at the end stage of life.

▪ Construct critical arguments for and against the proposition that the nursing profession should support the legalisation of euthanasia and assisted suicide.

I ntroduction

In 1990, in the United States (US), Janet Adkins, a 54-year-old newly diagnosed with early Alzheimer’s disease, died after pushing a red button on a suicide machine — or ‘mercitron’, as it has been called — designed by a retired pathologist, Dr Jack Kevorkian, whom she had approached for assistance to die (Gibbs 1993, 1990a). Adkins, who is reported to have ‘feared an excruciating future’, soon came to be viewed as a ‘symbol of all those patients who confront a horrible disease and vow to maintain some dignity in death’ (Gibbs 1990a: 70). Dr Kevorkian, meanwhile, found himself in the forefront of the pro-euthanasia debate and, as Time Magazine put it:

a standard-bearer for all those who fail to see a moral difference between unplugging a respirator and plugging in a poison machine.

(Gibbs 1990a: 70)

Despite being dubbed ‘Dr Death’, Dr Kevorkian continued his crusade for the legalisation of euthanasia/assisted suicide, or, as he called it, ‘medicide’ in the US (Gibbs 1993: 52; see also Brovins & Oehmke 1993; Kevorkian 1991). As part of this crusade, in December 1998 Dr Kevorkian was successful in getting authorities in the state of Michigan (US) to charge him with first-degree murder after he admitted, for the first time, having directly administered a fatal injection to one of his patients (Riley 1998a, 1998b, 1998c; see also Magnusson 2002: 28–32). In all other cases (130 in total), Dr Kevorkian admitted only to presiding over the suicides of his patient; that is, ‘instructed the patients and supervised them while they activated an injection from his so-called “suicide machine” ’ (Riley 1998c: ii; see also Riley 1999a, 1999b).

Dr Kevorkian’s case went to trial in March 1999, representing the fifth time he had been tried over the deaths of his patients. On 26 March 1999, the jury returned a verdict of second-degree murder and he was sentenced to serve 10–25 years in the Michigan State Prison (Magnusson 2002: 28–32). In passing her sentence, the judge presiding over the case stressed that the trial was not about ‘the political or moral correctness of euthanasia’, but about lawlessness and murder (AFD, DPA 1999). Referring to a national television broadcast several months earlier in which Dr Kevorkian dared legal authorities to arrest him for his actions, the judge responded:

You had the audacity to go on national television, show the world what you did and dare the legal system to stop you. Well, sir, consider yourself stopped.

(Judge Jessica Cooper, reported comments cited by AFP, DPA 1999)

In the Netherlands, during the same period, a very different scenario was at play. In contrast to the US, euthanasia and assisted suicide was, at the time of Janet Adkins’ medically assisted death, legally tolerated (although still a criminal offence). By the time Dr Jack Kevorkian had facilitated his first ‘assisted suicide’ in 1990, Dutch doctors had already participated in thousands of medically assisted deaths. In 1986, for example, the Royal Dutch Medical Association reported that there were between 5000 and 6000 cases of voluntary euthanasia each year in the Netherlands (British Medical Association 1986). In 1990, the overall incidence of euthanasia was estimated by formal sources to be between 4000 and 6000 deaths annually (de Wachter 1992: 24). In 2001 it was reported that approximately 2500 cases of euthanasia were notified to authorities in the previous year, with another 1000 cases going unreported ‘because of “grey” areas in the law’ (Mann 2001: 17). Some contend that the overall incidence of euthanasia is, in reality, unknown and, if informal sources are to be relied upon, could range from 2000 to 20000 cases a year (de Wachter 1992; Keown 1992; ten Have & Welie 1992).

Today, the Netherlands is one of only two countries (the other being Belgium) in which euthanasia is legal (euthanasia was legalised in the Netherlands in 2001, followed by Belgium in 2002) (de Beer et al 2004; Daverschot & van der Wal 2001; Dupuis 2003). This means that under certain clearly defined conditions that have undergone ‘subtle elaborations over the past three decades’, euthanasia and assisted suicide are no longer viewed by the courts as a punishable offence (Magnusson 2002: 64–5). In 1993, legislation was passed clarifying and affirming the strict conditions under which euthanasia and assisted suicide were permitted. The passage of this new law was reported at the time as giving the Netherlands the world’s most lenient policy on ‘mercy killing’ (Hirschler 1993: 7). Seven years later, the leniency of the Dutch ‘mercy killing’ laws was expanded even further when statutory support was given for the first time to the defence of ‘necessity’ (passed by the lower house of the Dutch parliament in November 2000, and the upper house in April 2001) (Magnusson 2002: 65). The defence of ‘necessity’ permits a doctor to avoid legal liability for assisted deaths on the grounds of professional duty; that is, ‘to reduce suffering and respect the autonomy of the patient’ and provided that he or she (the euthanasing doctor) can demonstrate that ‘due care’ was exercised in determining that the patient’s request ‘was voluntary and well-considered, that the patient’s suffering was unbearable, and that there is no prospect of improvement’ and no ‘reasonable’ alternative (Magnusson 2002: 65). Significantly, under the ‘due care’ requirements:

it is not necessary for the patient to be suffering physical pain: unbearable mental anguish is sufficient. Similarly, there is no requirement for the patient to be in a terminal phase of an illness, or indeed to be suffering from any (physical) condition at all. A physical disability, or a condition of ‘untreatable misery’ … will suffice.

(Magnusson 2002: 65)

The above legislative reforms have not only given the Netherlands the world’s most lenient policy on euthanasia and assisted suicide, but as some have noted has also given the world a ‘laboratory’ for ‘testing’ and ‘observing’ these practices — and one which has attracted many onlookers from both ends of the moral spectrum in regard to the moral permissibility of euthanasia. Certainly, the Netherlands is currently the only country in the world which is able to offer retrospective studies of substance concerning the practice of euthanasia and any emerging patterns or trends associated with it (see, e.g. Bindels et al 1996; Dupuis 2003; Onwuteaka-Philipsen et al 2003; van der Maas et al 1996; van der Wal et al 1996).

In 1996, Australia became the subject of international attention when it became the first country in the world to fully legalise active voluntary euthanasia. This followed the passage, in May 1995, of the Northern Territory’s controversial Rights of the Terminally Ill Act 1995, which came into effect on 1 July 1996. Almost 1 year later, however, the Act was overturned by the Australian Federal government — although not before five people had sought assistance to die under the Act. Of these people, four were successful in achieving legally assisted deaths; the only person not successful in achieving his wish was eligible for assistance to die under the Act but was ‘unable to find a specialist who was prepared to be one of the three doctors required under the Act’ to certify eligibility for an assisted death (Senate Legal and Constitutional Legislation Committee 1997: 11). To date, despite the success of the Australian Federal government in overturning the Northern Territory’s euthanasia legislation, proponents of euthanasia speculate that it will only be a matter of time before euthanasia and assisted suicide will be legal in not just one, but possibly all jurisdictions in Australia.

In 2002, in what has been described as an unprecedented and ‘landmark legal case’, a British High Court judge ruled that a competent 43-year-old woman with quadriplegia and unable to breathe unaided, had the ‘right to die’ and to have the ‘machine keeping her alive’ switched off ( Herald-Sun 2002: 7). This ruling stands just less than a decade after a House of Lords Select Committee report released in 1994 opposed legalising euthanasia in England (Magnusson 2002: 66). A year later in Australia, in what has also been described as a ‘landmark decision’, a similar ruling was made. In what has become known as the ‘tube woman case’, a Victorian Supreme Court judge ruled that a 68-year-old woman (known only as BMW) suffering from a rare and fatal brain disease, who had been kept alive for 3 years by artificial tube feeding, be allowed to die (Davies 2003: 5). The judge is reported to have said that her ruling would now make it possible for the woman’s advocate ‘to decide, on behalf of BMW, whether it is now time to allow her to die with dignity’ (Davies 2003: 5). It was noted, however, that once the tube feeds were stopped, it could take between 1 and 4 weeks for the woman to die. Margaret Tighe, President of Right to Life Australia, is reported to have criticised the court decision, arguing that it was ‘not an act of love to kill somebody by dehydration and starvation’ (Davies 2003: 5).

In 2005, after Hurricane Katrina had devastated the US city of New Orleans, a new and largely unanticipated dimension was added to the euthanasia debate, notably, climate change. In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, allegations were made that ‘mercy killings’ had occurred at the city’s Memorial Medical Centre, leading to autopsies being requested on 45 bodies taken from the hospital after the storm (Johnston 2005; Lugosi 2007). As the inquiries progressed, it was gradually revealed that four nonambulatory patients, aged between 61 and 90 years of age, had been ‘euthanised’ in an attempt to prevent their needless suffering in the face of having ‘no realistic chances of surviving in a stranded, incapacitated hospital’ (Curiel 2006: 2067). The four patients, who were allegedly given a combined lethal intramuscular dose of the drugs morphine and midazolam, were among 24 patients who died in the Life Care Unit situated on the 7th floor of the Memorial Medical Centre.

The environmental conditions at the time were extreme. According to one CNN report, the medical centre had been a storm refuge for up to 2000 people, where patients, staff and their families ‘rode out the storm inside’ (Griffin & Johnston 2005). However, as CNN goes on to report,

by Thursday, four days after Katrina hit, despair was setting in. The hospital was surrounded by floodwater. There was no power, no water and stifling heat. Food was running low. Nurses were forced to fan patients by hand. And outside the hospital windows, nurses … saw looters breaking into a credit union … The hours, and then days, passed with only the occasional boat or helicopter stopping by to pick up patients. On Thursday, according to people who were there, there was a shift in tone at the hospital …

(Griffin & Johnston 2005)

It is alleged that nurses started to discuss ‘who would be evacuated and, for the first time, who would not’, for example, patients who were ‘DNR’ (do not resuscitate) (Griffin & Johnston 2005). It was further reported that ‘at about the same time, some members of the hospital staff were discussing euthanising patients’ (Griffin & Johnston 2005). Although, none of the four patients in question were expected to die immediately from natural causes, were in pain, or had consented to the drugs they were given, they did have one thing in common: they were all the subject of a consented ‘Do Not Resuscitate’ (DNR) directive. As one commentator has noted, however, no one had warned the patients that ‘in case of a natural disaster, hospital administrators would interpret DNR to mean “Do Not Rescue” ’ (Lugosi 2007: 74).

In July 2006, a New Orleans physician (Dr Anna Pou) and two nurses (Lori Budo and Cheri Landry) were arrested and charged with second-degree murder in relation to the patients’ deaths, sparking public debate on whether the killings were ‘murder or mercy’ (Curiel 2006; Griffin & Johnston 2005; Johnston 2007; Lugosi 2007; Nossiter & Dewan 2006; Safer 2006, 2007; Skipp & Campo-Flores 2006). Commenting on the case, Curiel raised a number of important questions, including: What might lead a health care professional to consider euthanasia in such a situation? and Were the Memorial staff prepared to make life-and-death decision during a disaster, and, if not, what could have prepared them? — pointing out that tsunamis, earthquakes, fires and other calamities ‘are present and evolving threats that can rattle unprepared respondents to the core and expose complex ethical, legal and medical conundrums’ (Curiel 2006: 2067 & 2068).

While acknowledging the extreme conditions under which health care providers were operating at the time, Curiel nonetheless found it ‘unimaginable’ that effective team decision-making would have — and could have — led to a decision to euthanise patients (Curiel 2006). Referring to his own experience in the aftermath of Katrina, Curiel writes:

Katrina’s flood waters crippled emergency power generators, transforming hospitals into dark, fetid, dangerous shells. Extremely high indoor temperatures killed some people. We were under tremendous strain: in addition to the dire medical circumstances of many of our patients, we confronted uncertainty about our own evacuation, exacerbated by the tensions of threatened violence by snipers and frazzled soldiers and guards. I saw some competent professionals reduced to utter incoherence and uselessness as the crisis unfolded. I saw others perform heroic deeds that surprised me.

(Curiel 2006: 2067)

He concludes that if the allegations against the physician and two nurses in the Katrina case are ‘borne out’, then:

… such behaviour might be attributable to less effective group decision making, lack of a sense of control, or individual actions that were contrary to group decisions, in addition to environmental or medical conditions that were judged not to be survivable, requests of patients, or criminal intent.

(Curiel 2007: 2068)

Other commentators have been more circumspect. Lugosi (2007), for example, warns that the killings have served unacceptably to model ‘a new way to manage patients when natural disaster strikes — the non-consensual deceptive killing of patients that are too difficult to move because of logistics or lack of resources’ (p 76). Controversially, he has also suggested that racism and poverty may have influenced the decisions made that day, pointing out that another feature that all four patients had in common was that they were black and poor (p 78).

In June and July of 2007, the two nurses and then the physician were respectively all cleared of criminal charges after a New Orleans grand jury decided not to indict them ( American Medical News 2007; Jervis 2007). However, as CBS reports, ‘the case continues to resonate and raise questions about ethics, and compassion in what has been described as battlefield conditions’ (Safer 2007).

Euthanasia and assisted suicide continues to receive widespread attention both locally and globally, and remains the subject of much controversy. Central to the controversy is the fundamental question of whether a doctor should intentionally and actively assist a patient to die, and, if so, under what circumstances and by what means. These same questions can (and should), of course, also be asked of nurses — particularly given the fundamental role nurses play in caring for and promoting the dignity of patients who are incurably ill, suffering intolerably, dying (Asch 1996; Berghs et al 2005; Bilsen et al 2004; Crock 1998; Daverschot & van der Wal 2001; de Beer et al 2004; Gastmans et al 2006; van der Arend 1998), or, as has just been considered above, left hopelessly stranded by catastrophic emergency events linked to climate change.

In this chapter, attention is given to examining the nature and moral implications of the euthanasia/assisted suicide question for nurses. Attention is also given to clarifying what euthanasia is, how it differs from assisted suicide and ‘mercy killing’, and the kinds of moral arguments that can be raised both for and against the legitimation of euthanatic practices. It is hoped that by examining these and related issues, members of the nursing profession will move a step closer towards answering the following kinds of questions:

▪ How significant or important is the euthanasia/assisted suicide issue for the nursing profession?

▪ Should the nursing profession take a formal position either way on the euthanasia/assisted suicide question (e.g. should nursing organisations adopt formal position statements advocating a particular view on the moral permissibility or impermissibility of euthanatic practices, or is this a matter that should be left to individual nurses to decide conscientiously)?

▪ To what extent, if at all, should the broader nursing profession participate in public debate on the euthanasia/assisted suicide question (e.g. should nursing organisations actively lobby for the legalisation of euthanasia/assisted suicide)?

▪ In the event of euthanasia/assisted suicide being decriminalised, what (if any) should be the role of nurses in regard to assisting with or actually performing euthanasia and/or assisted suicide?

▪ How best can the nursing profession proceed to answer these and related questions (see also Johnstone 1996a)?

E uthanasia and its significance for nurses

Next to abortion, euthanasia is probably one of the most controversial bioethical issues to have captured the world’s attention. And, like the abortion issue, it is unlikely to be resolved to the satisfaction of all concerned.

Euthanasia and the so-called ‘right to die’ are not new issues for nurses. In Australia, one of the first articles addressing the subject was published as early as 1912 in the Australasian Nurses Journal. Reprinted from the British MedicalJournal, the article contains concerns and viewpoints which remain current — including the agonising question of whether euthanasia should be legalised. Citing an 1873 essay on the subject, the article contends that ‘a modified harikari should be made lawful in England’ (and, one presumes, her colonies, including Australia), and, quoting the essay’s author, that: ‘On the whole it cannot be doubted that the benefits resulting from a change in the law would be simply enormous’ (Lionel Tollemache, cited in the Australasian Nurses Journal 1912: 304).

While euthanasia may not be a new issue for nurses, it has nevertheless become a more complex, intense and significant one. Evidence of this can be found in the increased attention being given to the experiences of nurses in regard to euthanasia in both the professional and lay press over the past 20 years or so. In 1987, for example, the English nursing periodical Nursing Times carried a provocative report on the fate of four Dutch nurses who had been arrested in Amsterdam after it was alleged they had practised euthanasia on three hopelessly ill patients. The report concluded that, if the nurses were found guilty of killing the patients, they could face prison sentences of up to 20 years ( Nursing Times 1987: 8).

Almost a decade later, in another (although unrelated) case in 1995 in the Netherlands, a 38-year-old Dutch registered nurse was given a 2-month suspended prison sentence for performing active voluntary euthanasia on a patient suffering end-stage AIDS (Staal 1995: 7; van de Pasch 1995; van der Arend 1995; see also Daverschot & van der Wal 2001). What was particularly significant about this case was that the sentence was passed despite the fact that:

▪ the patient (who was a friend and colleague of the nurse) had specifically requested that the nurse perform the act of assisted death; and

▪ the procedure fully complied with legal regulations governing euthanatic practices in the Netherlands (for example, the patient had competently requested assistance to die, he was suffering from an end-stage illness, a second medical opinion had been obtained, and the procedure was fully attended to and supervised by a qualified medical practitioner [who, significantly, escaped sentence]).

(van de Pasch 1995: 108)

As I have discussed elsewhere (Johnstone 1996c: 21–2), this case helped to demonstrate the tenuous position of nurses in relation to euthanatic practices — even in countries where euthanasia and assisted suicide are ‘legally tolerated’. In this case, the court’s decision seemed to hinge on the view that euthanasia and assisted suicide were medical procedures of a nature that could not (and should not) be delegated to nurses. More specifically, the court clarified that the deed of ‘ultimate care’ (the procedure that is the act of euthanasia itself) could only be performed by a doctor and could not be delegated to anyone else (Daverschot & van der Wal 2001; Staal 1995: 7).

Nurses in the United Kingdom (UK) have also experienced significant problems in relation to the euthanasia issue. For example, in 1991, a UK registered nurse experienced threats of violence and obscene phone calls, was vilified by some sections of the media, and was made a scapegoat in the eyes of the public after reporting to the appropriate authorities that a terminally ill patient had died possibly as a result of being administered 10 mmol of potassium chloride by a consultant physician, Dr Nigel Cox (Hart & Snell 1992: 19). The incident was discovered after nurses noted the blatant documentation of the drug administration in the patient’s case history which ‘had been left in the nurses’ station for all to see’ (Hart & Snell 1992: 19). The registered nurse’s attempts to contact Dr Cox about the matter were unsuccessful. Not wishing to implicate other staff in the matter and recognising her professional duties as prescribed in the United Kingdom Central Council for Nursing, Midwifery and Health Visiting (1992) Code of Professional Conduct, the registered nurse decided that she ‘had no choice but to report the incident’. Accordingly she notified the director of nursing services and the unit general manager. One month later, Dr Cox was convicted of attempted murder at Winchester Crown Court, after the justice hearing the case rejected the argument that ‘Cox’s intention in injecting lethal quantities of a drug which lacked analgesic properties was to relieve pain, rather than to kill’ (Magnusson 2002: 26). He subsequently received a 1-year suspended prison sentence (Hart & Snell 1992: 19). He was not deregistered by the General Medical Council (UK), however, and continued to practise medicine. The registered nurse meanwhile carried a disproportionate burden of suffering for her actions.

Besides sometimes finding themselves unwitting witnesses to the illegal euthanatic practices of others, there is anecdotal evidence, some published research and a number of court cases suggesting that a small percentage of nurses (e.g. in the US, Hungary, Australia, England and the Netherlands) have also taken active steps to bring about the death of a patient themselves (Rozsos 2003; Magnusson 2002; Crock 1998; Kitchener 1998; Asch 1996; Walsh & Pirrie 1996; Staal 1995; Stevens & Hassan 1994; Kuhse & Singer 1992, 1993; Turton 1992). One commentator has even alleged controversially that British nurses are ‘often’ involved in performing euthanasia on patients:

British nurses are often involved in euthanasia; but that due to the illegality of euthanasia practices, it is difficult to assess the exact extent of the problem — particularly in a culture which prescribes that nurses should not ‘tell on colleagues’.

(Turton 1992: 92–3)

Euthanasia and assisted suicide is, however, a controversial issue for nurses in the UK (Johnstone 1996c). Significantly, the prestigious Royal College of Nursing (RCN), a leading professional nursing organisation in the UK, has historically and unequivocally rejected the role of nurses in participating in euthanasia. This position has been made explicit in an issues paper on living wills. In this paper, the RCN takes the following position (RCN 1994):

The RCN believes that this [euthanasia] is contrary to the public interest and to the medical and nursing ethical principles as well as to natural and civil rights.

It further asserts:

The RCN is opposed to the introduction of any legislation which would place on doctors or nurses a responsibility to respond to a demand for termination of life from any patient or from their relatives.

In 2003, the RCN’s opposition to euthanasia was reaffirmed by its General Secretary, Dr Beverly Malone, who reportedly stated in an RCN media release:

The RCN is against euthanasia and assisted suicide. Euthanasia is illegal and the RCN does not condone it. The RCN believes that the practice of euthanasia is contrary to the public interest, to nursing and medical ethical principles as well as patients’ civil rights. The RCN is opposed to the introduction of any legislation which would place the responsibility on nurses and other medical staff to respond to demand for termination of life from any patient suffering from intractable, incurable or terminal illness.

(StaffNurse.com 2003)

In 2004, after a survey of its members found that 70% did not support a ‘softening’ of its stance against the legalisation of euthanasia, the RCN again reiterated its opposition to the legalisation of euthanasia and assisted suicide (McDougall 2004; Hawkes 2005). In response to a House of Lords select committee on an assisted dying Bill, the then RCN Vice-President, Maura Buchanan (now president of the RCN), was reported to have said: ‘Our patients do not want nurses and doctors to be skilled in delivering lethal injections’ (quoted by BBC News 2005).

The euthanasia/assisted suicide question has also proved to be a significant professional issue for Australian nurses. For example, in January 1995, recognising the seriousness of the euthanasia issue for members of the nursing profession, the Royal College of Nursing, Australia (RCNA) took the unprecedented step of releasing for comment a discussion paper entitled ‘Euthanasia: an issue for nurses’ (Hamilton 1995). As I have discussed elsewhere (Johnstone 1996b), the RCNA received over 70 responses to this discussion paper from concerned and interested nursing organisations, groups and individuals from around Australia. The responses received represented nurses working in a variety of clinical areas and fields of nursing (including education) and reflected a great diversity of knowledge, opinion, values and beliefs about euthanasia and assisted suicide. In some cases, the responses also demonstrated an overwhelming need for information and guidance on how best to respond to the uncertainty, controversy, complexity and perplexity that has become so characteristic of the right to die movement generally. Perhaps most confronting of all, however, was the emerging difficult question of whether the nursing profession should formally and publicly support the legalisation of active voluntary euthanasia. Related to this was the equally confronting question of whether representative nursing organisations should adopt a formal position statement either supporting or rejecting the role of nurses in active voluntary euthanasia and assisted suicide. Not surprisingly, while the responses demonstrated the need to raise and address these troubling questions, they fell far short of offering a definitive answer to them. Recognising the complexity and perplexity of the issue, the RCNA subsequently commissioned, as part of its professional development series, a monograph entitled: The politics of euthanasia: a nursing response (Johnstone 1996a). The purpose of this monograph was not to provide nurses with definitive answers to the difficult questions posed by the euthanasia debate. Rather, it was to advance a discussion that would enable nurses ‘to formulate their own thinking and viewpoints on the subject and to be able to contribute to broader professional discussion on the whole issue of the right to die’ (Johnstone 1996b: 22). In July 1996, the RCNA also issued its first position statement on voluntary euthanasia and assisted suicide — subsequently revised and reaffirmed respectively in 1999 and 2006 (Royal College of Nursing, Australia 1996, 1999, 2006). This position statement primarily focuses on clarifying the illegal status of euthanasia/assisted suicide in Australia, acknowledging that there exists a diversity of moral viewpoints on the euthanasia issue, reminding nurses of their professional responsibility to be reliably informed about the ethical, legal, cultural and clinical implications of euthanasia and assisted suicide, and recognising and supporting the appropriateness of nurses taking a ‘conscientious’ position on the matter.

The RCNA’s initiatives (just outlined above) were to prove extremely timely, coinciding as they did with the enactment of the Northern Territory of Australia’s controversial Rights of the Terminally Ill Act 1995 which came into effect on 1 July 1996. As already stated in the opening paragraphs of this chapter, the passage of this legislation earned Australia the controversial distinction of being the first country in the world to legalise active voluntary euthanasia. Of significance to nurses (and to this discussion) is that the legislation anticipated and provided for nurse participation in active voluntary euthanasia and assisted suicide (either by way of preparing, or being delegated the task of actually administering, a substance to terminate life [see section 16(1); see also Trollope 1995: 21]). What, arguably, was troubling about the legislation’s provisions in regard to nurse participation was that they had been enacted even before the broader nursing profession itself had:

▪ clarified its position on the euthanasia/assisted suicide question (at the time, the issue had not been widely discussed in the Australian nursing literature, and policy statements on the subject were either non-existent, inadequate or only at draft stage)

▪ taken the necessary steps to ensure that its membership had been fully informed about and adequately prepared to deal with the complex range of political, social, cultural, moral, legal and clinical issues raised by public policy innovation and legal ratification of active voluntary euthanasia and assisted suicide (Johnstone 1996b).

Significantly, in May 1996, less than 2 months before the Rights of the Terminally Ill Act 1995 (NT) came into effect, the Nurses’ Board of the Northern Territory took the unprecedented step of formulating and ratifying a formal position statement on euthanasia (see Nurses’ Board of the Northern Territory Position Statement on the Nurse’s Role in Euthanasia, included in full as Appendix 5 in Johnstone 1996a). This position statement was keyed to the Rights of the Terminally Ill Act 1995 (NT) and sought to clarify the role and function of nurses in relation to the Act’s provisions. Specifically, the position statement supported:

▪ the role of nurses assisting in the voluntary euthanasia of competent patients; and

▪ the rights of nurses to conscientiously refuse to participate in the euthanasia of patients (Johnstone 1996c: 36).

The position statement also outlined the obligations of nurses in regard to the ethical and legal aspects of euthanasia, employment policies, professional competence and education (Johnstone 1996c: 36–7).

As stated earlier, the decriminalisation of euthanasia and assisted suicide in the Northern Territory of Australia was short-lived. Less than 1 year after its enactment, intense political pressure resulted in the Rights of the Terminally Ill Act 1995 (NT) being overturned by the Australian Federal government. Currently, euthanasia and assisted suicide is illegal in Australia, and anyone who wilfully assists a person to die would be viewed by the courts as having committed the criminal offence of homicide (Wallace 1991: 265, ss. 14–65; see also Forrester & Griffiths 2005; Magnusson 2002). As Dix et al warn (1996: 339, s. 1223):

It should be made very clear from the outset that the law does not allow mercy killing. Where a person takes steps to end, or hasten the end of another person’s life with the intention or the knowledge that this is likely to be the consequence of his or her actions, such a person may be liable for murder or, should death not eventuate, attempted murder. The sentence for murder is imprisonment for life, although in some jurisdictions (NSW, Vic, ACT) there is a discretion in the trial judge to order a sentence of less duration …

Despite the current legal prohibition against euthanasia and assisted suicide in Australia, Magnusson (2002: 272) asserts that it is a ‘virtual certainty’ that many medical practitioners are ‘heavily involved in assisted death’. Magnusson (2002: 24, 32) points out, however, that ‘doctors are rarely punished for their involvement in assisted death’ — even when making ‘front page news’ with admissions of having performed euthanasia. This is the situation not only in Australia, but also in the UK and the US. For example, in the US, between 1950 and 1991, only 11 doctors were prosecuted for euthanasia (Cox 1993: 234). Thus, while euthanasia as such is illegal, it nevertheless seems to be tolerated where it can be shown that the intention was ‘therapeutic’ (i.e. to alleviate suffering) rather than homicidal (i.e. to kill).

In Australia, proponents of euthanasia/assisted suicide speculate that it will only be a matter of time before euthanasia and assisted suicide will be legal in all jurisdictions in Australia. In light of the looming health and welfare implications of climate change (scientists are warning that ‘changes to the environment are rapidly becoming a threat to many of our life support systems’ [Anderson 2007: 10; Haines & Patz 2004; McMichael et al 2006]), and the perceived need of some to have an ‘exit strategy’ if and when stranded by climate change, impetus for the legalisation of euthanasia is likely to take on a whole new dimension. Given these predictions, there is ample room to speculate that it will only be a matter of time before Australian nurses will once again have to grapple with the complex and perplexing questions raised by the legalisation of euthanasia/assisted suicide, and, in particular, the possible and actual implications of this for nurses at a personal, professional, societal and political level (Johnstone 1996a).

P ublic opinion on the euthanasia/assisted suicide issue

In reaching a position on the euthanasia/assisted suicide issue, it might be tempting to appeal to and/or be persuaded by public opinion on the matter. Consider the following.

Over the past two decades, public opinion polling in Australia, Canada, Europe and the US suggests majority support (around 75%) for the legalisation of euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide (Marcoux et al 2007; Voluntary Euthanasia Society [VES] 2003; Somerville 1996; Kuhse 1991; Australian Dr Weekly 1990: 9; Kuhse & Singer 1988; Humphries 1983; Radic 1982; see also Gallup polling at http://www.gallup.com/). In Australia, for example, opinion polls conducted by Morgan and Newspoll respectively during 1995 and 1996 showed 75–78% public support for physician-assisted suicide. In 2007, a national Newspoll report (prepared for Dying with Dignity Victoria) found that around 80% of the 2423 respondents surveyed by telephone thought that doctors ‘should be allowed to provide a lethal dose to a patient experiencing unrelievable suffering and with no hope of recovery’ (Newspoll Market Research 2007: 6). In 2002, a UK public opinion poll indicated that 81% of those surveyed supported the legalisation of euthanasia for people suffering unbearably from a terminal illness (VES 2003). Similar support has also been indicated by public opinion polls conducted in France (88%), Belgium (72%), Germany (75%), Italy (75%), the Netherlands (85%), Spain (70%) and the US (75%) (VES 2003). Just what is to be made of this public opinion, however, is open to question.

As discussed earlier in Chapter 2 of this book, public opinion is not a reliable guide to moral conduct; all that it tells us is that a certain group of people hold a particular opinion, not that the opinion held is ‘morally right’ all things considered. In short, it tells us nothing about the moral acceptability or the moral authority of the opinion held. We must therefore look elsewhere (i.e. beyond public opinion) to guide our deliberations on whether euthanasia and assisted suicide are morally right or wrong. It is to looking ‘elsewhere’ that the remainder of this chapter will now turn. This exploration will begin firstly by clarifying what euthanasia is, and how, if at all, it differs from other end-of-life practices such as assisted suicide and ‘mercy killing’. This, in turn, will be followed by a critical examination of views popularly raised for and against the legitimation of euthanasia and assisted suicide.

D efinitions of euthanasia, assisted suicide and ‘mercy killing’

E uthanasia

The term euthanasia comes via New Latin from Greek eu (meaning ‘easy’, ‘happy’ or ‘good’) and thanatos (meaning ‘death’); it is translated literally as ‘good death’ or ‘happy death’. Contrary to popular opinion, the Greeks did not use the term euthanasia (or equivalents) to imply either ‘a means or method of causing or hastening death’ (Carrick 1985: 127). Rather, it was used in a broader and somewhat metaphorical sense ‘to describe the spiritual state of the dying person at the impending approach of death’ (p 127). Historical evidence also suggests that euthanasia, as we understand it today, was in fact prohibited in ancient medical circles (p 81). Plato, for one, even went so far as to suggest that physicians who attempt to poison another ‘must be punished by death’, whereas the lay person who attempted such a thing should only be fined — indicating that physicians were regarded as having the greater burden of responsibility to refrain from causing death (p 83). Carrick comments that ‘if someone’s life was terminated without his (sic) consent, normally this was prima facie a case of homicide’ (p 128).

Contemporary English definitions of euthanasia vary. The Oxford English Dictionary, for example, defines it as ‘the action of inducing a quiet and easy death’, and the Collins Australian Dictionary (2005) as ‘the act of killing someone painlessly, especially to relieve suffering from an incurable illness’. Webster’s Dictionary, similarly, defines euthanasia as ‘an act or practice of painlessly putting to death people suffering from incurable conditions or disease’.

Whether euthanasia is any of these things, however, is a matter of some controversy. For example, we can imagine a case of ‘inducing a quiet and easy death’ which is a case not of euthanasia but of cold-blooded murder. I could, for example, slip a calming and sleep-inducing sedative into my fit grandmother’s nightcap, and the moment she starts blissfully sleeping in her armchair administer to her a lethal dose of intravenous morphine. My sole intention might be nothing more than to secure her premature death so that I may receive the large inheritance I know she has left me in her will. There is something about this example which, to borrow from Beauchamp and Davidson (1979: 295) ‘omits all the subtle aspects of our notion of euthanasia’. Likewise, we can imagine cases involving patients with incurable diseases or conditions who would nevertheless not be candidates for euthanasia. Diabetes, for example, is an incurable disease, and colour blindness an incurable condition. Yet, we would not, I think, regard either of these incurable states as grounds for euthanasia.

The notion of ‘painlessly’ inducing death is also unhelpful. We can, for example, imagine a painless means of causing death (e.g. injecting a lethal substance through the side arm of an intravenous line, or removing someone from a life-support system or withholding food and fluids) but where the death itself is nevertheless painful and/or distressing (e.g. where a patient is acutely aware of the sensations of suffocation after being taken off a respirator or after being given a large dose of narcotics, or is aware of both hunger and thirst sensations when food and fluids have been withheld). Just because the means of death was ‘pain-free’, it does not always follow that the death itself was a ‘good death’.

All three dictionary definitions are also inadequate in that they say nothing about the kinds of reasons which should be considered for killing another person, leaving it wide open for motivations of self-interest to be admitted (Beauchamp & Davidson 1979: 295). The questions remain: How should euthanasia be defined? How can we be sure that a given act is an act of euthanasia rather than some other kind of act, such as murder or unassisted suicide?

In a classic article on defining euthanasia, Beauchamp and Davidson (1979) argue that for an act to be an instance of euthanasia, it must satisfy at least five conditions.

1. Intentionality. Death must be intended and not be merely accidental, and further must be intended by at least one other human being.

2. Suffering and evidence of suffering. Here suffering may be in the form of conscious pain, mental anguish, and/or serious self-burdensomeness (as may occur in cases of high quadriplegia, or tetraplegia, or the like). This interpretation of suffering fully upholds the view that ending a person’s pain is not always tantamount to ending that person’s suffering (see also Cassell 1982, 1991; Kuhse 1982; Hill 1992; Starck & McGovern 1992). In assessing a person’s level of suffering, every effort must be made to gain ‘sufficient current evidence’ (Beauchamp & Davidson 1979: 301); in this instance, it is simply not enough to rely on mere guesswork or on supposition based on ignorance.

3. Reasons for death and the means of death. Beauchamp and Davidson contend that death-causing acts must be motivated by beneficence or other humanitarian considerations (such as the demand to end suffering). Killing acts which are not motivated by these things are not acts of euthanasia, but murder. Further to this, any means of death chosen must also be of a nature that does not cause more suffering than is already being experienced (Beauchamp & Davidson 1979: 302).

4. Painlessness. This condition is related to the previous one and demands, quite simply, that any death act performed must be as painless and as merciful as possible. Beauchamp and Davidson (1979: 303) explain that if the means of bringing about death causes more suffering than if that particular means was not used, then the individual will be effectively deprived of a ‘good death’.

5. Non-fetal humanity. Beauchamp and Davidson (1979: 303) contend that if this simple qualification is not included then we would not be able to distinguish acts of abortion from acts of euthanasia.

Beauchamp and Davidson (1979) maintain that the five conditions they have formulated supply a ‘non-prescriptive definition’ of euthanasia, and thus one which avoids dictating a particular moral conclusion. Whether they have succeeded, however, is another matter. The definition still seems ethically loaded, and therefore carries prescriptive meanings. Nevertheless, the five conditions given supply an important step towards the formulation of an operational definition of euthanasia, and one which can be meaningfully applied in the euthanasia debate.

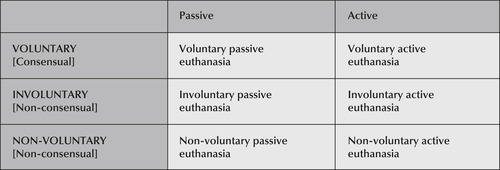

Active euthanasia, meanwhile, typically involves a deliberate act (or commission) which results in the patient’s death. The deliberate act of administering a lethal injection or a lethal dose of pills is an example of active euthanasia. This type of euthanasia is sometimes referred to as positive euthanasia. Passive euthanasia, on the other hand, involves a deliberate omission or the withholding of certain life-supporting cares and treatments. Withholding antibiotics, nutrition and fluids, mechanical life supports, or other life-supporting measures from terminally or chronically ill patients are examples of passive euthanasia. This type of euthanasia is sometimes referred to as negative euthanasia (Glaser 1975).

The six types of euthanasia just outlined can be expressed diagrammatically, as shown in Figure 10.1.

|

| Figure 10.1 |

A ssisted suicide

The term ‘euthanasia’ (and, more specifically, voluntary active euthanasia) is sometimes used interchangeably with the term ‘assisted suicide’. As I have explained elsewhere (Johnstone 1996c), this interchanging usage is not, however, strictly correct. While it is acknowledged that there may be no morally significant difference between voluntary active euthanasia and assisted suicide (see Brock 1993: 204; Parker 1994: 34–42), there is nevertheless a qualitative (experiential) difference between them. With assisted suicide, a qualified medical practitioner supplies the patient/client with the means (e.g. a prescription for a lethal dose of drugs) for taking his or her own life but, unlike in the case of voluntary active euthanasia, it is the patient/client (not the doctor) ‘who acts last’ (Brock 1993: 204; Campbell 1992: 276). To put this another way, in the case of active euthanasia it is the qualified medical practitioner who kills the patient/client; whereas in the case of assisted suicide, the patient/client kills him or herself. Interestingly, while there may indeed be no morally significant difference between voluntary active euthanasia and assisted suicide (in both instances the ultimate choice rests with the patient/client, both involve assistance from a qualified medical practitioner [or his or her proxy, e.g. a nurse] and both result in the foreseeable and intended death of the patient/client suffering from an irreversible medical condition), the law, public policy and public opinion have all distinguished between them (Brock 1993; Glick 1992; Forrester & Griffiths 2005). A notable US example here can be found in the 1994 Oregon Death with Dignity Act (known as ‘Measure 16’) which legalised physician-assisted suicide (in the form of prescribing a lethal dose of medication), but not active voluntary euthanasia (Magnusson 2002: 64; Kuhse 1995). It has also been argued controversially that physician-assisted suicide is more defensible and hence preferable to active euthanasia since with the former ‘the willingness [by the patient] to commit suicide gives compelling evidence of the patient’s desire to die’ (Dixon 1998: 29).

‘M ercy killing’

A third terminology which has found usage in discussions on euthanasia is that of ‘mercy killing’. Although this term is also sometimes used interchangeably with the term ‘euthanasia’ it can nevertheless be distinguished from euthanasia on a contextual basis. Specifically, as Glick explains (1992: 81–2):

Mercy killing is not the same as voluntary active euthanasia since many killings are committed without patient request or consent — typically an elderly husband shoots his terminally ill and unconscious or Alzheimer’s disease-stricken wife. But the cases almost always exhibit wrenching long-term personal suffering and sacrifice and financial ruin … They evoke sympathy for both killer and victim and perpetuate interest in the legalisation [sic] of voluntary active euthanasia, which some believe might eliminate the compelling need that desperate people feel for killing their hopelessly ill spouses.

A classic example of a ‘mercy killing’ scenario can be found in the highly publicised Australian case of Raymond Riordan, a 71-year-old man, who admitted trying to kill his 71-year-old wife who was suffering from advanced Alzheimer’s disease (Haslem 1998: 3). Although pleading guilty and convicted of attempted murder (which could have carried a jail sentence of up to 25 years), Riordan was freed after being placed on a 3-year good behaviour bond. Justice Cummins of the Victorian Supreme Court is reported to have said that while Riordan had acted illegally, he had ‘sought to relieve (his) wife of her terrible suffering and indignity’ (Haslem 1998: 3). Describing Riordan as a ‘person of compassion and selflessness, totally devoted to his wife’, Justice Cummins stated that Mrs Riordan’s ‘deteriorating health had had a “catastrophic” effect on her husband, who sought treatment for depression’ (Haslem 1998: 3). Mr Riordan’s son, meanwhile, is reported to have told the court that he had ‘never seen two people more devoted to each other than his parents’. He is reported to have described how (Haslem 1998: 3):

Every morning they would rise at six o’clock and have brekkie [breakfast] and go for walks … They would probably cover 30km [sic] and there probably was not more than 100m [sic] they weren’t hand-in-hand.

Outside the court, Mr Riordan’s son was further reported as stating (Haslem 1998: 3):

It’s dad’s wish that not one other person … has to go through what he’s been through. He would like to see the law-makers of this country … do something about laws covering euthanasia.

V iews for and against euthanasia/assisted suicide

Like other controversial bioethical issues, euthanasia and assisted suicide have proponents and opponents. Attitudes towards them range from liberal and moderate acceptance to absolutist conservative prohibition. It is to examining some of the various viewpoints for and against euthanasia and assisted suicide that this discussion will now turn.

V iews in support of euthanasia

Those who support euthanasia typically take the view that it is morally wrong to allow people to suffer unnecessarily. As one author writes:

the most horrible thing in the world for us, living and sentient beings, is inexorable suffering pain, without any possible compensation when it has reached this degree of intensity; and one must be barbarous, or stupid, or both at once, not to use the sure and easy means now at our disposal to bring it to an end.

(Reiser 1975: 28)

Popular views advanced in support of euthanasia (and, in particular, in support of legalising it) fall roughly under four main augmentative categories:

1. arguments from individual autonomy and the right to choose;

2. arguments from the loss of dignity and the right to the maintenance of dignity;

3. arguments from the reduction of suffering;

4. arguments from justice and the demand to be treated fairly.

(adapted from Beauchamp & Perlin 1978: 217)

A fifth and controversial category of argument raised in support of euthanasia is that, in some instances, patients have a ‘duty to die’ (Hardwig 2007; Beloff 1992: 52–6) and furthermore that it might even be a violation of a person’s ‘freedom of conscience’ not to respect this duty (Lewis 2001: 60–2). A sixth argument emerging in support of euthanasia derives from all of the above, but with the significant difference that the decision-point for euthanasia is not a patient’s hopeless medical condition imposed by injury or illness, but rather a person’s hopeless life condition imposed by climate change.

Arguments from individual autonomy and the right to choose

We generally accept that people have a right to choose. And, as we have already seen in Chapter 3, the moral principle of autonomy demands that we respect other people’s choices, even if we consider them to be mistaken or foolish. The only grounds upon which a person’s autonomous choices can be justly interfered with is if they stand to impinge seriously on the significant moral interests of others. Proponents of voluntary euthanasia argue that the right to choose includes the right to choose death (abbreviated as ‘the right to die’). Given the right to die, this means that others (including the state) should not interfere with a person’s decision to die, and in some instances may even entail a positive duty to assist a person to die — as in cases where a person desires death but is physically unable to end his or her own life. Voluntary euthanasia is thought to be justified here on grounds of autonomy and the demand to respect a person’s autonomous wishes.

An important example of this can be found in the comments of Baume (1996: 17) who writes that voluntary euthanasia is justified because ‘it is a self-regarding victimless action from an individual decision in a matter which affects individuals alone’.

Arguments from the loss of dignity and the right to the maintenance of dignity

Related to the demand to respect a person’s autonomous choices is the further demand to respect and maintain a person’s dignity. Advances in medical technology have increased medicine’s capacity to prolong a person’s life. Its methods, however, are not always humane, and can seriously erode a person’s self-concept, character, sense of self-worth and self-esteem, and the like. As Beauchamp and Perlin (1978) point out, some patients ‘are not only subjected to intense and abiding pain, they are often aware of their own deterioration, as well as of the burden they have become to others’ (p 217). They conclude that under these conditions ‘it seems uncivilised and uncompassionate’ not to allow patients to choose their own death. Euthanasia in some pain states as well as in some chronic disease states may well be the most dignified option.

Arguments from the reduction of suffering

Suffering may be defined as a state of severe distress that people experience when some crucial aspect of themselves, their being or their existence is threatened (Kahn & Steeves 1986; Cassell 1991). It is important to clarify that while pain is a major cause of suffering, suffering itself is ‘not confined to physical symptoms’ (e.g. people can be in pain, yet not be ‘suffering’) (Cassell (1991). Suffering may, for example, derive from other aspects of ‘personhood’ — including the cognitive, emotional, spiritual, social and cultural aspects of a person’s identity — not just their physical aspect. Moreover, when any one or a combination of these aspects is threatened, a person may simultaneously give a cognitive, emotional, spiritual, social and other (cultural) meanings to that threat and respond accordingly (Fry & Johnstone 2008).

Suffering is generally regarded as morally unacceptable and, as discussed in Chapter 3 of this work, morality demands that, where possible, people (including the very young as well as others across the life span) should be spared or prevented from suffering unnecessarily. In cases where patients’ suffering is intense, protracted, unendurable and intractable, it seems cruel to deny them the choice of death as a means of release from their suffering. Euthanasia in these kinds of cases is said to be justified on grounds of ‘prevention of cruelty’ or ‘mercy’ (Beauchamp & Perlin 1978: 217). It is also thought to be justified on the grounds that people have the indisputable right to judge their suffering as unbearable, and the concomitant right to request euthanasia to end their unbearable suffering (see, e.g. Admiraal 1991: 11). This, in turn, is grounded in the fact that, despite the achievements of modern medicine, doctors still cannot relieve all suffering (Magnusson 2002; Pool 2000; Admiraal 1991; Cassell 1991).

Arguments from justice and the demand to be treated fairly

It is argued that everybody is entitled to be treated fairly and to share equally the benefits and burdens of life. To deny patients the option of being spared intolerable and intractable suffering is to treat them unfairly, and to make them carry a burden which others do not have to carry. Furthermore, to deny patients the right to die (i.e. in a manner and time of their choosing) is to impose unfairly on them the values of others. Only patients, or those intimately involved with them (e.g. family and friends), can judge what is in their own best interests. For others to deny patients the right to choose death is therefore to violate unfairly these patients’ autonomy, dignity and entitlement to be spared the harms that will flow from suffering intolerable and intractable pain. Where euthanasia is the only thing that can end patients’ intolerable and intractable pain and/or suffering, it stands as a morally just alternative.

Arguments from altruism and the ‘duty to die’

It is argued that in certain circumstances (such as in the case of old age, chronic illness or when medical treatment is futile) it may be a person’s duty to volunteer for euthanasia (Hardwig 2007; Kilner 1990; Beloff 1992; Schwartz 1993) and that it might also be a violation of a person’s right to freedom of conscience to interfere with the exercise of this duty (Lewis 2001: 60–2). Beloff (1992: 53), for example, apparently finds it quite plausible that:

the mere thought of becoming a burden to others, not to mention a drain upon society, would suffice to make [some] choose voluntary euthanasia as the only honourable course of action still open to them.

In situations where a person’s primary caregivers are burdened to the point where they cannot live their lives fully and are themselves beginning to suffer as a result of their burden of care, euthanasia, argues Beloff, is not only permissible, but required. Beloff (1992: 54) explains that this is because:

If there is a duty to die it is one that arises from our basic human predicament, the fact that we are dependent on others, and it is a duty we owe to those we cherish.

Hardwig (2007) holds a similar position, contending that sometimes ending one’s own life is ‘simply the only loving thing to do’. He writes (pp 94–5):

I may well one day have a duty to die, a duty most likely to arise out of my connections with my family and loved ones. Sometimes preserving my life can only devastate the lives of those who care for me. I do not believe I am idiosyncratic, morbid or morally perverse in believing this. I am trying to take steps to prepare myself mentally and spiritually to make sure that I will be able to take my life if I should one day have such a duty … Tragically, sometimes the best thing you can do for your loved ones is to remove yourself from their lives. And the only way you can do that may be to remove yourself from existence.

In regard to the assumed right to freedom of conscience, it might be argued that ‘the decision whether or not to commit [assisted] suicide is essentially a matter of conscience’ — the terms of which can be formulated on either religious or secular terms — which must be respected (Lewis 2001: 61).

Arguments from climate change

It is argued that climate change is poised to have a significant, far-reaching and possibly devastating impact on human health and psychological wellbeing, and that in instances where the impact is likely to be extreme people might want to — and indeed have the right to — ‘opt out’. The usual arguments from individual autonomy, dignity, the reduction of suffering, justice, and even a duty to die (as considered in the bioethics literature, too numerous to mention here), all support such a stance.

The prospect of people seeking euthanasia as an ‘exit strategy’ to escape a world severely disrupted by desperate food and water shortages, a crumbling infrastructure, and a soul-destroying loss of amenities has been given graphic expression in the 1973 classic (now cult) science fiction movie Soylent Green (directed by Richard Fleischer) (Wikipedia 2007a). Loosely based on Harry Harrison’s 1966 science fiction novel Make Room! Make Room! (available as a Penguin paperback re-issue), the film is set in the year 2022, and depicts a ‘Malthusian catastrophe that occurs because humanity has failed to pursue sustainable development and has not halted uncontrolled population growth’ (Wikipedia 2007b). At a key point in the film, the character Sol Roth (played by Edward G Robinson) opts for euthanasia after he becomes dispirited by a lack of books (because of a lack of paper, ‘real books’ were out of print) and the hideous lack of electricity, water, food and other amenities once taken for granted in everyday life. (Sol, a former college professor of literature, dies in a room adorned by motion pictures of the beautiful Earth as it once was, and which are shown only to those being euthanised [Wikipedia 2007a, 2007b].)

Soylent Green, although science fiction, contains some salutary lessons. When extreme weather events (including periods of high temperatures, droughts, torrential rains, and flooding) affect local populations, they are generally able to adapt ‘to the local prevailing climate via physiological, behavioural, and cultural and technological responses’ (McMichael et al 2006: 860). Scientists are warning, however, that extreme weather events (as well as other natural disasters such as earthquakes, tsunamis and fires) often ‘stress populations beyond those adaptation limits’, resulting in serious health risks and related poor health outcomes (McMichael et al 2006: 860; see also Haines & Patz 2004). Notable among the adverse health consequences that people can experience (and are already experiencing) are thermal stress (which may also precipitate or exacerbate heart attack, stroke and chronic respiratory disease), food poisoning, vector-borne infections and other infectious diseases, increased allergies, malnutrition, injuries, mental health disorders, and deaths (McMichael et al 2006; Haines & Patz 2004). Scientists further warn that, due to the social, demographic, economic and political disruptions it causes, climate change has other indirect or ‘knock on’ health effects as well. That is, because of the significant risks that climate change poses to infrastructure, amenities, regional food yields, water supplies, and so on, it can further disrupt individual and population health (McMichael et al 2006: 865, 866).

In a feature on global warming, National Geographic has highlighted that ‘things that normally happen in geologic time are happening during the span of a human life time’ (Appenzeller & Dimick 2004: 8–9). Given this, and the scientific warnings outlined above, it is understandable that people might reach a point where they would prefer to choose a peaceable death than to go on living a life hopelessly stranded by the impact of irreversible climate change.

C ounter-arguments to views supporting euthanasia

Not surprisingly, those who are against euthanasia are not moved by these kinds of arguments. The anti-euthanasia response typically entails three main approaches: (1) to assert a number of counter-claims and counter-arguments against the views put forward in support of euthanasia; (2) to assert a number of distinctive arguments against euthanasia; and (3) to reject altogether the notion of passive euthanasia (killing by omission) on the grounds that there is a morally significant difference between directly killing a person and merely letting a person die ‘naturally’ (referred to in the bioethics literature as the ‘killing/letting die distinction’).

Autonomy and the right to choose death

While the moral principle of autonomy is well established in Western moral thinking, it nevertheless has limits. Whether ‘autonomy’ was ever meant to stretch so far as to impose a moral duty on a doctor or a nurse to comply with a patient’s request for euthanasia — to intentionally and actively assist that patient to die — is an open question. If complying with a patient’s request for euthanasia has the foreseeable consequence of harming or affecting prejudicially the significant moral interests of others (e.g. the doctor[s] or nurse[s] receiving the request, or the patient’s family and friends), there is considerable scope for arguing that the doctor(s) and nurse(s) in question have no duty to perform euthanasia, no matter how autonomous the patient’s request for it. Further, given the complex nature of the morality of euthanasia, it is rather simplistic to hold that euthanasia can be justified on the grounds of patient autonomy alone without consideration being given to other important moral considerations which might also have a significant bearing on a patient’s choosing euthanasia/assisted suicide, and on a doctor’s, a nurse’s, a family member’s or a friend’s providing it.

Appeals to autonomy to justify euthanasia and assisted suicide are, however, problematic on another account. Paradoxically, acts of euthanasia/assisted suicide carried out in response to a patient’s autonomous request, destroy the very basis of their justification. According to Safranek (1998), while autonomy is necessary for the existence of a moral act, it is not sufficient to justify an act. As he explains (p 34):

The justification of the act will hinge on the end to which autonomy is employed: if for a noble end, then it is upheld; if depraved, then it is proscribed. It is not autonomy per se that vindicates an autonomy claim but the good that autonomy is instrumental in achieving. Therefore an individual cannot invoke autonomy to justify an ethical or legal claim to acts such as assisted suicide; rather he [or she] must vindicate the underlying value that the autonomous act endeavours to attain.

Since autonomous requests for euthanasia and assisted suicide are socially threatening (they threaten human survival), it is appropriate that the autonomy of individuals requesting such threatening acts (euthanasia/assisted suicide) be circumscribed — at least until such time it is clarified and agreed just what kinds of ‘good’ autonomy should be invoked to achieve (Safranek 1998: 34).

(It is important to note here that autonomy discourse is extremely powerful, making challenges to it difficult. So successful has been the promotion of autonomy, and the assumed sovereign rights of individuals to exercise self-determining choices, that the imperatives of these things — especially in the case of euthanasia/assisted suicide — have come to seem ‘so self-evident to all “right thinking people” that to question them seems almost perverse’ [Moody 1992: 50]. Those who do question them risk being publicly ridiculed and dismissed by opponents as ill-informed and ‘illogical’, or worse as being ‘insulting’ to vulnerable and oppressed groups [see, e.g. the reported comments in the Senate Legal and Constitutional Legislation Committee 1997: 71, 176].)

Dignity and the right to die with dignity

Dignity and dying with dignity does not necessarily entail choosing death over the artificial prolongation of life. The demand to respect and maintain a person’s dignity might equally entail respect for a person’s autonomous wish that ‘everything possible be done’ to prolong or sustain her or his life — and to sustain a sense of hope that is fundamental to living that life meaningfully, even though (and when) dying. Here, it is important to understand that the ethical controversies surrounding the care of dying patients are not just about management at a technological, medical or institutional level. As Campbell (1992: 255) points out, they should also be seen ‘as a sign of a deeper crisis of meaning in our culture’, and as an indication of how impoverished our society has become in ‘assessing the significance of suffering, dying and death as part of a whole human life’. Given this, as Campbell goes on to explain (p 255):

The emergence of the individual asserting inviolable rights to self-determination becomes intelligible in this void as a way to create meaning through a freely-chosen style of life and an authentic manner of death.

One way to respond to this crisis of meaning is to ‘provide compassionate presence to the sufferer’, not to ‘end the suffering by killing the sufferer’ (Campbell 1992: 269, 276). Another is to deny altogether the philosophical bases for a ‘right to die’ (see, e.g. Kass 1993).

Suffering and the demand to end it

Suffering is not just a medical problem; it is also an existential problem involving profound questions concerning the meaning and purpose of human life and destiny (Neimeyer 2001; Spelman 1997; Attig 1996; Campbell 1992; Starck & McGovern 1992; Amato 1990; Klemke 1981). To ‘end suffering by killing the sufferer’ is, to borrow from Campbell (1992: 276), to misunderstand ‘both suffering and ourselves in a way that threatens [infinitely] our moral integrity’.

Justice and the demand to be treated fairly

To deny patients the right to choose treatment — including the artificial prolongation of ‘hopeless life’ — is as unjust as to deny patients the right to choose death. Denying patients’ requests for ‘everything possible to be done’, where this conforms with their notions of dignity, meaning, value and quality of life, is to impose unfairly on them the values of others. As in the case for euthanasia, only patients (or those close to them) can judge what is in their best interests, and they must be permitted to make these judgments.

Altruism and the ‘duty to die’

In some circumstances, people may have a conscientious ‘duty to live’ in order to spare the pain of their grieving loved ones, who desire their ill loved one to live ‘as long as possible’. Being dependent on others is not necessarily being a burden on them (see, e.g. Kanitsaki 1994, 1993). Even if dependency does become burdensome — either for the dependent person or her or his carers — it is not clear how, if at all, this gives rise to a so-called ‘duty to die’. At best, it may only substantiate ‘our basic human predicament’ that:

the very experience of illness, and more fundamentally the process of aging that inevitably culminates in death, not only reveals our shared vulnerability and dependency, but also that we are all subject to some kind of ultimate powers beyond our control. Through our knowledge and technology we may aspire to a mastery of nature and the immortality of the gods, but we continually receive reminders of our dependency and finitude. From this it follows that any control we assert over our dying is already limited, and that dependency and dignity are not mutually exclusive.

(Campbell 1992: 270)

At worst, to embrace a ‘duty to die’ may be to embrace an all-pervasive sense of pessimism and hopelessness which would blind people to understanding that ‘the lives of even the terminally ill are precious and matter, right up to the last second of breath’ (Mirin, reported by Gibbs 1993: 53). And it may risk blinding people to the fundamental insight which has been articulated so well by the late French philosopher and feminist, Simone de Beauvoir (1987: 92), that, while all people must die, death is still an accident, and that, even if people know this, and consent to it, death remains ‘an unjustifiable violation’ (de Beauvoir 1987: 92). By this view, therefore, to embrace a duty to die emerges as an embracement of the unjustifiable violation of human life and all that it stands for. It also risks the perversion of morality — and of its ultimate aim, notably, how best to live the ‘good life’. Finally, if currency is given to the notion of people having a ‘duty to die’, this might have the undesirable effect of adding ‘to the distress and guilt [conscience] of those who wondered whether they were too great a burden on others’ (Muirden 1993: 14).

Climate change and the desire to have an ‘exit strategy’

There is no denying that climate change is serious and its adverse health effects potentially devastating. However, human culture is extremely adaptable and, as scientists are also advising, ‘many communities will be able to buffer themselves (at least temporarily) against some of the effects of climate change’ (McMichael et al 2006: 866). To ‘opt out’ of climate change by opting out of life, is to opt out of one’s civic responsibility to mitigate climate change and to adopt a proactive response to environmental justice that would be of benefit to all (Gostin 2007).

S pecific arguments against euthanasia

Specific arguments commonly raised against euthanasia (and the need to legalise it) include:

1. arguments from the sanctity-of-life doctrine

2. arguments from clinical uncertainty, misdiagnosis and possible recovery

3. arguments from the risk of abuse

5. arguments from discrimination

6. arguments from irrational or mistaken or imprudent choice

7. the ‘slippery slope’ argument.

Arguments from the sanctity-of-life doctrine

A popular argument raised against euthanasia draws heavily on the sanctity-of-life doctrine and contends that, since life is sacred and inviolable, nothing (not even intolerable and intractable suffering) can justify taking it. Sanctity-of-life arguments against euthanasia run something like this:

1. human life is sacred, and taking it is wrong

2. euthanasia is an instance of taking human life; therefore

3. euthanasia is wrong.

Whether human life is sacred, and whether taking it is always wrong is, however, a matter of philosophical controversy (Singer 1993; Kuhse 1987).

Arguments from clinical uncertainty, misdiagnosis and possible recovery

An argument often used against euthanasia is that which speaks to the risk of clinical uncertainty (ambiguity), misdiagnosis and the possibility of recovery. Doctors diagnosing life-threatening medical conditions are not infallible and can (and do) make mistakes (Craig 1994; Wilkes 1994). Furthermore, patients can sometimes recover spontaneously and unexpectedly from devastating and/or terminal illnesses — for reasons not always understood or accepted by medical scientists (for an insightful exploration of people’s capacity to heal and to recover unexpectedly from life-threatening conditions, see Gawler 2001; Dossey 1993, 1991; Chopra 1989). A poignant example of this can be found in the case of the noted best-selling author of The Women’s Room, Marilyn French. In 1992, French was diagnosed belatedly with metastasised oesophageal cancer. Her treating doctor at the time was extremely pessimistic about her prognosis, advising French that she had ‘terminal cancer, that there was no hope for cure or remission, and that [she] was not to think of that’ (French 1998: 34). Of this moment, French writes (p 34):

What was he saying? Hope, but not too much? Hope, but don’t expect a cure? What was I to hope for, then? He emphasised that mental attitude was crucial to anything they did. I spoke up, assuring him that I had strong powers of concentration and that I wanted to hope … But he wasn’t listening; he was talking over me. There was no hope for a cure, he said …

French, however, rejected the pessimism of her physician and simply ‘decided’ to survive. Accordingly she ‘twisted’ what medical information she had on oesophageal cancer to her purpose. For example, she seized on an article that stated ‘one in five people treated with extreme measures survive non-metastasised esophageal cancer for five years’ and decided those figures applied to her (despite her metastases). In French’s words, ‘I decided I had one chance out of five. I simply made it up’ (French 1998: 35). By the end of that day, she had obliterated the word ‘terminal’ from her memory; and within a couple of days, she had increased her odds of survival to be one in four and had ‘repressed any sense that [she] was deluding herself’ (pp 35–6). After going through what French describes as a ‘season in hell’ involving years of pain, dread and severe illness, she reached ‘a plateau of serenity’ (p 237). At the time of writing an autobiographical account of her experience of survival (published in 1998), French stated that, although suffering from a number of symptoms related to the damage caused to her bodily systems by the intense radiotherapy and chemotherapy treatment she received, she was feeling ‘relatively well’ and secure in the knowledge that the aches and pains she felt were not an indication of cancer (which had been cured).

There is also the possibility that new cures might be found for certain life-threatening conditions. For example, stem cell research (Keirstead 2001; Keirstead et al 2005; Lim & Tow 2007) and nanotechnology regenerative medicine research (Stupp 2005) are heralding a new era of medicine, together with renewed hope for the remedial treatment (including permanent cures) of such conditions as spinal cord injuries, diabetes, Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease. (For a futuristic view of curative possibilities in medicine, see also ‘The Body’ [part 1] of the Discovery Channel’s three-part science documentary 2057, details at http://dsc.discovery.com/convergence/2057/about/about.html.) If a cure for serious spinal injuries or Alzheimer’s disease were found, people living with these conditions might, for example, not request assistance to die as they are now doing.