CHAPTER 1. THE ADVANCED PRACTICE NURSE IN PALLIATIVE CARE

Kim K. Kuebler, James C. Pace and Peg Esper

A role-delineation study differentiating the CNS and NP was published by the American Nurses Association (ANA) and can be accessed at www.ana.org. The Oncology Nursing Society also completed a role-delineation study that differentiates the roles of the CNS and NP and has began to offer separate certification exams for these two roles (available at www.ons.org).

For the purposes of this chapter, the advanced practice nurse (APN) is identified as being either a CNS or an NP providing care and services to an adult patient population. It is with the understanding that the ANP is responsible for and has an active clinical management role in diagnosing, interpreting, and prescribing for individual patients in the palliative care setting. NPs are allowed to prescribe in all 50 states, whereas the CNS can currently prescribe in 30 states (available at www.nacns.org).

THE ROLE OF THE ADVANCED PRACTICE NURSE IN PALLIATIVE CARE

The APN who has undergone additional education in the care and management of adult patients is in an ideal position within the health care delivery team to ensure coordinated and continuous care for patients and families who are affected by chronic debilitating disease. While palliative care is appropriate for both adult and pediatric patients, the focus in this text is the adult patient and APNs who provide care to this patient population. APNs can serve as the conduit for the patient and family as they traverse the multiple dimensions associated with advanced disease. These dimensions include symptom burden, functional capabilities, communication patterns, and the psychoemotional and spiritual issues that interfere with quality of life.

The APN’s ability to perform comprehensive physical evaluations, order and interpret diagnostics, and prescribe appropriate medications while receiving reimbursement allows this clinician to become a valuable and important member in the patient’s plan of care (Kuebler, 2003). The APN can be instrumental when initiating palliative interventions throughout the patient’s disease trajectory (from diagnosis until death), reducing symptoms and promoting a seamless care model that reduces a fragmentation of care (Davis, Walsh, LeGrand, et al., 2002; Kuebler, 2003). It is the coordination and continuous care provided by the APN throughout the disease course that can help to reduce patient abandonment and isolation from within the healthcare system.

APNs not only provide comprehensive palliative care in a continuous and coordinated fashion but can do this by offering the patient and family compassion along with skilled assessment, interventions, and ongoing evaluation throughout the course of advanced disease until death. This clinician meets the discipline recommendations in palliative care as defined by the World Health Organization (1990):

▪ Substantial body of knowledge

▪ Recognized skill sets requested in consultation and clinical practice

▪ Evidence-based practice, a result of disseminated research data in peer review publications

▪ Development of professional organizations

▪ Growing number of APNs seeking training and additional education in the field

▪ Extensive bibliography

Davis and colleagues (2002) have further identified essential skills necessary for palliative care clinicians to include effective communication, informed decision making, competent management of clinical complications, symptom control, psychological care, care of the dying, and coordination of care (Davis et al., 2002). The APN who integrates palliative interventions into the patient’s plan of care is able to incorporate these skills into practice. The APN is able to provide the patient with his or her advanced knowledge of pathophysiology, pharmacology (pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic metabolism), and the ability to use appropriate evidence-based interventions (Kuebler, 2003). The APN who is in a collaborative practice arrangement with a physician is able to manage the complex needs of the patient by ordering and interpreting diagnostics, prescribing appropriately, and identifying prognostic indicators that help to set the stage for caring conversations that may shift the goals of care from curative to palliative. The APN is able to identify, support, and make the appropriate referrals that address the multidimensional needs of the patient and family within communities (Kuebler, 2003).

DIFFERENTIATING THE ROLES OF THE ADVANCED PRACTICE NURSE

Today is an exciting time for APNs who are defining and influencing the care of individuals, families, and communities as well as nursing care delivery systems. Most healthcare systems acknowledge four major APN “specialties.” The certified registered nurse anesthetist (CRNA), the certified nurse midwife (CNM), the clinical nurse specialist (CNS), and the nurse practitioner (NP). Each and every advanced practice specialty draws from the rich history of the discipline of nursing while addressing a different societal need for health care. For purposes of discussions related to palliative care, this section (and chapter) address the description and differentiation of the CNS and NP roles.

The Clinical Nurse Specialist

The CNS is an RN with a graduate degree (master’s or doctoral degree) leading to preparation as a CNS. The CNS specializes in a particular care setting (critical care, home care, community care) as well as in a specific disease or health issue (diabetes, medical-surgical, pulmonary, trauma). The CNS is deemed a clinical expert in the application of theoretical principles and research-based knowledge in regard to this chosen area of specialization in setting and practice. The CNS’s scope of practice is generally defined as encompassing three distinct spheres of influence (Lyon, 2005):

1. Patient/family (direct care)

2. Nursing personnel (advancing the practice of nursing)

3. Organizational/network of care (advancing the organizational management of care)

Practice is usually designated as within a specified interdisciplinary team (e.g., oncology services) or a particular service within an institutional setting (e.g., nursing services or department of internal medicine). Most often, it is the employer that defines the nature and scope of the CNS’s sphere of influence, provides and funds the position either totally or in part, and determines how specific outcomes are to be evaluated and by whom. The National Association of Clinical Nurse Specialists (NACNS) (2004) statement on clinical nurse specialists practice and education defines the core competencies for the CNS in each of these core spheres. Additional direct and indirect care aspects of the CNS include indirect roles as consultant-liaison, staff advocate, peer educator, change agent, policy analyst, patient educator, product evaluator, researcher (to include contributing scholarship to the literature), supervisor, mentor, and community advanced practice nurse (Hawkins & Thibodeau, 2000). Currently, there is a shortage of CNSs across the country. During the 1990s, many hospitals and academic centers were pressured to downsize or eliminate CNS positions as a result of reductions in reimbursables to hospitals, the increased costs of care, and the “nonreimbursable” nature of many, if not most, CNS roles (Hawkins & Thibodeau, 2000).

Current challenges for APNs who function in CNS roles include the absence of standardized credentialing requirements for CNS practice that allow for uniformity across state lines. This has led to differing philosophies regarding the educational preparation for the CNS, a defined scope of practice (despite the development of core CNS “competencies”), whether a “second” license is needed for an expanded scope of practice to include prescriptive authority in some states, and how to ensure competence in specialty areas of practice where no current examination exists. There is an evolving need for the CNS to continue to contribute to the literature to support advance nursing practice with a focus on specific disease and care settings, outcomes evaluation based on nursing interventions (best practices) in patient care, and the systematic evaluation of evidence-based innovations in nursing practice. These contributions support the valuable role of the CNS and the impact that they can make on patient care (Lyon, 2005).

The Nurse Practitioner

NPs are usually defined by a specified patient population: family NP (FNP), adult NP (ANP), gerontology NP (GNP), women’s health NP (WHNP), psychiatric-mental health NP (PMHNP), acute care NP (ACNP), and pediatric NP (PNP). NP curricula share certain core content areas (advanced pathophysiology, pharmacotherapeutics, advanced health assessment, research and theory development, role development) and then explore pertinent specialty content according to designated populations of need and interest. It is generally recognized that the primary activities/functions of the NP include screening, physical and psychosocial assessment by means of taking health histories and performing physical examinations, patient care management to include follow-up when deviations from the norm are detected, continuity of care, health promotion, problem-centered services related to diagnosis, identification and mobilization of resources, health education, and patient and group advocacy (Hawkins & Thibodeau, 2000). A key component of these functions is the management of pharmacologic therapeutics in all 50 states across all therapeutic specialties and in all locales (Towers, 1991) (Box 1-1). APN curricula are challenged to emphasize quality of care, financial as well as time-based productivity, evidence-based outcomes, and practice cost outcomes, while contributing to equity of care (Allan, 2005). Current challenges include the need to develop practice models that create effective evidence-based interventions for populations differing in terms of ethnicity, culture, gender, and geographic location.

Box 1-1

• Assists consulting physician with treatments and/or examinations

• Consults with physician regarding history, physical examination, assessment, and/or plan of care as needed and as required by protocol (protocol manual on file and duly signed by all parties)

• Dictates or writes clinic notes and any needed discharge summary

• Makes rounds with or in consultation with sponsoring physician

• Obtains health history and performs physical examinations

• Provides health counseling and guidance and instructions to patients regarding diet, medications, disease education, exercise, discharge plans, and follow-up care

• Performs procedures/treatments in consultation with physician with appropriate documentation of same

• Writes or issues orders that are authenticated by both NP and consulting physician

• Determines diagnostics and procedures necessary to augment physical findings and interprets laboratory, radiographic, and clinical data in planning the course of management

• Prescribes medications for patients according to the approved formulary and/or protocol (state dependent)

• Takes call for specified periods of time with physician backup and responds to emergencies within his or her professional limitations

THE MACMILLAN NURSE

The historical and positive role that the Macmillan nurse has demonstrated throughout the British communities can easily be applied to that of the American APN providing palliative care. Macmillan nurses are posted throughout the United Kingdom; they are highly respected for their palliative care skills and in many ways are the public face of specialist palliative care in the United Kingdom (Skilbeck & Seymour, 2002).

The Macmillan nurse’s key role is to influence patient care by providing direct and indirect services. Indirect services involve strategic and policy-making activities (e.g., administrative, legislative) that influence patient care. They accomplish this by empowering and supporting primary care providers by advising on and assessing the development of patient care plans and clinical practice and through teaching and education (Macmillan Cancer Support, 2006). Direct care offered by Macmillan nurses is at the request of primary care providers and usually occurs when individual patients present with complex problems that would require specialist nurse intervention in the management and planning of their care (Macmillan Cancer Support, 2006). The focus of this role is clinical expertise, education, research, and management, contributing to multidisciplinary activities in various settings (e.g., hospital, long-term care, community home care) (Jack, Oldham, & Williams, 2003).

The Macmillan nurse is a CNS who is required to demonstrate a range of abilities that include expertise in and knowledge of advanced disease management and clinical leadership skills that enable other health care professionals to develop palliative expertise. Effective and therapeutic communication skills are required to ensure that their knowledge and skills are passed on to primary care providers (Macmillan Cancer Support, 2006).

A study that evaluated Macmillan nursing outcomes in patients with advanced cancer (n = 26) revealed that Macmillan nurses provided important assistance to patients by facilitating clinical discussion between patient and physician during medical consultations. They participated in co-coordinating actions resulting from those discussions and navigating the patient and his or her family through the healthcare system (Corner, Halliday, Haviland et al., 2003). It was pointed out in this study that Macmillan nurses spent more time with patients and their caregivers, answering questions, explaining medical terminology, and assisting patients to feel more secure about their treatment and what was happening to them—along with understanding the rationale behind specific diagnostics and whether further investigations were necessary and/or how to understand the results of these findings. Macmillan nurses often serve as the intermediary between the medical treatment team and the patient (Corner et al., 2003).

The described role of the Macmillan nurse can be easily applied to the role of the APN in various care settings. However, the NP with a distinct medical management role in palliative care could also benefit by applying attributes used to describe the role of the Macmillan general practitioner (GP). The Macmillan GP is a primary care physician specially trained in palliative care (Macmillan Cancer Support, 2006).

The Macmillan GP in the United Kingdom serves as a facilitator to improve the care of patients with cancer by providing collaborative practice with physicians in primary, oncology, and palliative care settings (Macmillan Cancer Support, 2006). Aspects of this role that can be applied to the APN in palliative care include the following (Macmillan Cancer Support, 2006):

▪ Being an APN in active practice for at least 3 years, with clinical experience in managing patients with cancer and palliative care needs

▪ Showing an active interest in oncology and palliative care with a good understanding and awareness of the emerging cancer and palliative care evidence and strategies nationally and internationally

▪ Demonstrating interest in education and training in palliative care

▪ Having comprehensive interpersonal, communication, and presentation skills

▪ Working as a member of the multiprofessional (interdisciplinary) team, appreciating different roles and responsibilities of the team

▪ Maintaining skills and knowledge in cancer, internal medicine, and palliative care

Lessons Learned from Macmillan Nurses

The presence of palliative care in the United States is predominantly in the setting of end-of-life care—the APN’s valuable role in this area of health care is not well understood, with little or no data to support the positive outcomes that can occur between the APN, patient, and family. Palliative care in general, and in nursing specifically, has been accompanied by a preoccupation with questions regarding the benefits that may arise from referral to a palliative care service, or to a nurse specialist, despite the long history of advocating outcomes in nursing research (Corner, Clark, & Normand, 2002). This may come from the analogy of medicine’s evidence-based practice, which attempts to measure the impact of disease management on indicators of health outcomes (Corner et al., 2002). Therefore, the role of the APN in palliative care should reflect a genuine preoccupation with demonstrating the effectiveness of the care provided by APNs or whether a specialized palliative care service is of value (Corner et al., 2002). Macmillan nurses have been able to articulate and successfully demonstrate the value of their role in the care and management of patients living with and dying from advanced disease through clinical outcomes. APNs may consider applying the Macmillan nurse framework and the collection of clinical outcomes in their role as a palliative care provider in the United States. As APNs collaborate and clarify their roles in the provision of palliative care, they can aim to apply the best evidence to practice that can help to further inform and influence the development of policy and practice in palliative nursing. Clinical outcomes that will come from this role can further be used to correlate with conventional evidence to provide the best care for the patient and his or her family (Corner et al., 2002).

THE ROLE OF THE ADVANCED PRACTICE NURSE WITHIN THE INTERDISCIPLINARY TEAM

Ideally, all APNs work in team settings where a pooling of talent between and among a variety of professional staff members contributes to the holistic care of patients and families. APNs function independently in terms of their appointed roles and licensure stipulations but contribute interdependently with other team members to ensure seamless and comprehensive healthcare services across systems. The paradigm of the interdisciplinary team (IDT) is “we” where this pool of talent, knowledge, and skills contributes to gains in quality and productivity. Healthcare experts who are members of an IDT might include other medical providers (e.g., MD, NP, CNS, physician assistants [PAs], pharmacists, dietitians, RNs, social workers, occupational and rehabilitation specialists, chaplains, ancillary support service personnel, and community health care personnel). Serving as a team player necessitates functioning with maturity—respecting other professionals, sharing roles and responsibilities, promoting a spirit of cooperation and respect, and abandoning antagonism and conflict (the “us” versus “them” mentality as opposed to a needed spirit of cooperation and respect) (Venegoni, 2000).

Unfortunately, current reimbursement patterns foster the model where a single clinician is reimbursed without considering the skills and services rendered by additional providers or the specified needs of individuals and families. Changes in reimbursement patterns that provide for team-practice reimbursement rates are under consideration by certain payers. Such reimbursement mechanisms would identify substitutive services (where multidisciplinary clinicians offer the same services), supplemental services (multidisciplinary clinicians offer a core set of services plus additional or supplements), and complementary services (where multidisciplinary clinicians offer different services). Using this model, reimbursement is tied to services rather than to the discipline of the provider (Davis & Gilliss, 1998). It is therefore important for APNs who integrate unique provider skills into the care and management of patients in many therapeutic areas to collect the important outcomes data that demonstrate comprehensive, collaborative, coordinated, and cost-effective care.

THE ROLE OF THE ADVANCED PRACTICE NURSE IN DIVERSE SETTINGS

Data from the ANA place the number of advanced practice nurses in the United States at just under 100,000 (ANA, 2005). Approximately 58,000 APNs are certified through the American Nurses Credentialing Center (2005). The body of APNs is made up of NPs, CNSs, CNMs, and CRNAs. The American Medical Association estimates that there will be more than 106,500 NPs in the United States in 2006 (Heitz & Van Dinter, 2000). A greater emphasis has been placed on the integration of palliative care within the healthcare arena as a general construct, and the role of the APN in this setting has become an area of increased interest, focus, and research.

Nurses are in a unique position to provide interventions into the cascade of symptoms that patients often experience along the continuum of heath and illness, from birth until death. APNs with additional education and experience are even more uniquely qualified to have an impact on the care of these patients. The role of the APN is being addressed in legislative settings nationwide. Over 250 bills have been introduced in state legislatures across the country that address the practice of APNs, and approximately 20 bills have been enacted at the time of this writing (ANA, 2005).

Specifically focusing on the role of the NP, it is clear that these clinicians have found a place in almost every healthcare setting. This provides NPs with multiple opportunities to facilitate palliative care interventions. An example is the NP providing services for patients with end-stage renal failure. Many of these patients die before receiving hospice services—a result of chronic dialysis and an unwillingness to accept hospice care for fear of relinquishing ongoing dialysis. The NP in this setting has many challenges, which include the physical, spiritual, emotional, psychosocial, and ethical domains of providing care. It is important that these professionals have the resources available to address and meet the palliative care needs of this patient population. Currently, however, it is not uncommon for limited attention to be given to palliative care issues within established practice guidelines and protocols for chronic, life-limiting illnesses (Emnettm, Byock, & Twohig, 2002; Mast, Salama, Silverman et al., 2004).

The oncology NP can demonstrate a unique role in providing palliative care. Depending on the size and type of setting, the NP’s day is filled with the urgent complaints made by patients experiencing symptoms related to therapy, managing clinical trials, and coordinating treatment plans. It is not uncommon, however, for this clinician to integrate palliative interventions into the management of patients receiving “noncurative” therapies. Many institutions do not have the luxury of an inpatient palliative care service or a palliative consultation service. As these patients move from aggressive therapy to treatments that are purely supportive, the NP has the opportunity to create seamless transitions for patients and their families. The NP can participate in the responsibility of managing the care of patients admitted to home hospice care—this intervention provides the patient with valuable continuity and coordination of care.

Regardless of the setting within which the APN practices, there are many opportunities for taking the lead to ensure quality palliative care for patients and their families. This need has been reiterated in the Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care (National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care, 2004).

PROTOCOLS AND GUIDELINES: WHAT ARE THEY?

Guidelines

Guidelines are statements developed to provide practitioners and patients with information to assist in decision making regarding healthcare choices for specific clinical situations. They represent the culmination of experience, literature reviews, and state-of-the-art practice typically agreed on by consensus panels (Emanuel, Alexander, Arnold et al., 2004).

The ANA Social Policy Statement, revised in 1996, defined the four essential features of nursing practice (ANA, 1996a), to consider when developing practice guidelines:

▪ Attending to the full range of human experiences and responses to health and illness, without restriction—differing from the problem-focused approach

▪ Integrating objective data with knowledge gained from an understanding of the patient’s or group’s subjective experience

▪ Providing a caring relationship that facilitates health and healing

The ANA also maintains that “advanced practice registered nurses integrate education, research, management, leadership, and consultation into clinical roles, and they function in collegial relationships with nursing peers and other professionals and individuals who influence the health environment” (ANA, 1996b).

These elements of basic and advanced nursing practice are intermingled throughout specific clinical guidelines to improve the quality of life for those patients with a life-limited diagnosis (English & Yocum, 1998). While many APNs practice independently, many state regulations require a collaborative practice arrangement, written or verbal, agreed on between an APN and a physician. Palliative care often presents clinicians with challenges outside of the scope of practice and expertise of many nurses. It is therefore important for the APN to identify possible interdisciplinary resources, including a physician versed in palliative medicine along with other members of the interdisciplinary team, to address and support the multiple needs of the patient living with chronic debilitating disease.

These nursing elements encourage the APN to define and develop specific guidelines with a collaborative physician. A carefully developed practice agreement that includes practice guidelines between the APN and collaborating physician allows the APN to practice independently within the scope of nursing practice and without the need to adhere to a rigid, preset course of action. The APN has the ability to use his or her level of expertise, scope of practice, and continued relationship with the patient and family to provide individualized and compassionate care.

Protocols

Protocol is typically used within diplomatic circles but can also be applied to a variety of venues. Scientists have long used the term to define experiment or research designs. The dictionary defines protocol as a “correct code of conduct” (Yahoo Education, 2005).

In applying this definition to the APN’s practice, it can be used as an agreed-on set of expectations that are carried out when performing a specific procedure or task or managing a specific disease and/or symptom. As previously mentioned, the APN’s scope of practice is determined by the specific state practice act, institutional mandates, or both. Collaborative practice agreements (discussed later in this chapter) may also specify how protocols are utilized and incorporated into daily clinical practice.

The Use of Guidelines and Protocols in Clinical Decision Making

Guidelines and protocols should permit the practitioner to incorporate the use of sound clinical judgment when providing individualized patient care, as opposed to rigid adherence to a step-by-step process. A rigid “cookbook” approach to symptom management does not take into account the individual situation and the resultant needs and responses of the patient. The pharmacological management of frequently occurring symptoms in a patient with end-stage disease requires careful assessment, individualized sequential trials of therapy, and ongoing evaluation and monitoring. The management of any symptom requires patience, experience, and ongoing education with the patient and family. While this is true in all clinical situations, it is especially important in palliative and end-of-life care. Applying algorithms specific to an individual symptom such as pain, dyspnea, or delirium may not necessarily produce the desired outcome. While the use of algorithms and care maps should not be discouraged, careful attention should be given to individual patient and family variations, their responses, and the context of care.

Guidelines can help to facilitate care toward best known practices, based on the current evidence. They serve to decrease the variability in care and to improve quality (Emanuel et al., 2004; O’Connor, 2005). It is important to update clinical guidelines or protocols with the integration of current evidence-based interventions. Maintaining an ongoing knowledge of the current research provides the APN with state-of-the-art interventions (evidenced-based practice). The use of guidelines and protocols that incorporate proven therapies benefits patients in everyday practice without sole reliance on personal intuition or anecdotal experiences.

The APN in palliative care is exploring ways and means to embrace evidence-based practice with a model of practice that includes clinical state, setting, circumstances, research evidence, patient preferences, healthcare resources, and clinical expertise. APNs practice from guidelines and protocols that should be tied into the growing body of science that is defining and promoting the field of palliative medicine.

STATE PRACTICE GUIDELINES

Each state’s individual nurse practice act determines the specific scope of practice for the APN. State nursing practice acts define the role and responsibilities for practicing APNs to include the following (Berry & Kuebler, 2002; Buppert, 1999; Kuebler & Moore, 2002):

▪ Participate in a collaborative practice arrangement with a physician

▪ Practice under specific protocols and/or guidelines or practice agreements regarding specific diagnosis, evaluation, and management of disease

▪ Licensure requirements and specialty certifications

▪ Prescribing responsibilities (prescriptive authority), the need for delegated prescribing, or whether there is a need for the APN to obtain a DEA (Drug Enforcement Agency) provider number

▪ Ability to obtain reimbursement under state Medicaid programs

The rules governing APN practice routinely come from the state board of nursing (Buppert, 1999). Often, the board of medicine is also involved in APN practice guidance. To learn about specific state rules, access the state board of nursing or seek information from the state nursing association. The American Academy of Nurse Practitioners (AANP) is a valuable resource for this information and can be accessed at www.aanp.org.

Collaborative Practice Arrangement

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) in 1998 amended the definition of collaboration to read as follows:

Collaboration involves systemic formal planning and assessment and a practice arrangement that reflects and demonstrates evidence of consultation, recognition of statutory limits, clinical authority, and accountability for patient care, according to a mutual agreement that allows the physician and the nurse practitioner to function as independent as possible (Federal Register, 1998).

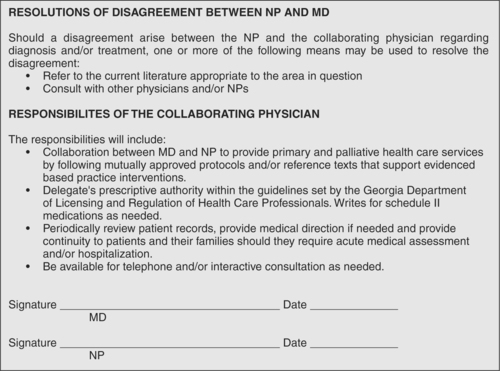

Successful collaboration requires a re-thinking of the traditional medical hierarchical model of practice (Lysaught, 1986). In a collaborative practice arrangement, the APN and the physician can focus on a holistic approach to patient care. Collaborators are partners and not substitutes for one another who agree to ongoing participation in the patient’s plan of care (Berry & Kuebler, 2002; Lysaught, 1986). Figure 1-1 provides an example of a collaborative practice arrangement between an independent NP and a collaborating physician.

|

|

| Figure 1-1 |

It is important to note that regardless of specific state practice acts that do or do not require a collaborative practice arrangement, in order for the APN to submit for a federal Medicare reimbursement provider number, a physician must be identified in the application process. A consulting and supportive physician relationship provides medical direction in the event that the APN’s clinical decision making occurs outside the scope of his or her practice (Buppert, 1999).

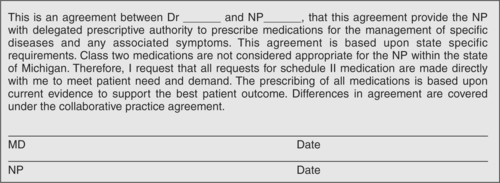

Delegate Prescriptive Authority

Currently in the United States, more than half of the states allow NPs to prescribe schedule II medications. Some of these states require a delegated authority, meaning that the collaborative physician delegates prescribing practices to the NP. Other states may limit prescribing practices to certain medication schedules (Kuebler, 2003). An example of a delegated prescribing arrangement is given in Figure 1-2.

|

| Figure 1-2 |

REIMBURSEMENT ISSUES

The legislation that provided authorization for APNs to receive direct reimbursement for the provision of reimbursable Medicare services was passed under the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 and became effective in January 1998 (AANP, 2004). Since this time, ANPs have been providing reimbursable care for patients covered under Medicare Part B providers. Prior to this legislation, care was provided exclusively by physicians (AANP, 2004). Under this law, APNs may provide, order, and refer patients under their own PIN (personal identification number) and UPIN (universal provider identification number). The bill states that the services of the APN cannot be restricted by site and/or geographical areas. Under this new legislation, APNs are no longer limited to billing under the “incident to” clause, which suggests that the APN practice exclusively with an attending physician and provide clinical practice for stable follow-up patients, excluding any new patients or returning patients with a new problem (AANP, 2004). The incident-to billing arrangement will reimburse the collaborative physician at 100% reimbursement, whereas NPs who bill under their own PINs receive 85% of what physicians bill under the same reimbursable codes.

The PIN and UPIN numbers for all physicians and practitioners are being replaced by the NPI (national provider identifier). The objective for establishing an NPI is to assign a unique provider number to each provider of health care services. This will eliminate the need to use multiple numbers for billing and insurance purposes (Towers, 2004). It is anticipated that this new identification system will be used throughout healthcare in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) and regulations related to the transportability of provider data among various systems (Towers, 2004). Initiated on May 23, 2005, all healthcare providers can apply for their NPI; information on the process to obtain an NPI is available at http://nppes.cms.hhs.gov. As of July 1, 2005, a hard-copy application was made available (obtain at Web site provided). The requirement for use of the NPI in reimbursement transactions is planned for May 23, 2007, for individual providers and May 23, 2008, for small businesses (Towers, 2005). More valuable information about reimbursement can be obtained from the AANP Web site (www.aanp.org).

Medicare Prescription Drug Improvement and Modernization Act

The Medicare Prescription Drug Improvement and Modernization Act (MMA), better known as the Medicare Prescription Bill, included significant language influencing NP practice. After 2006, Medicare recipients without pharmaceutical coverage may want to enroll in the voluntary Medicare Endorsed Pharmaceutical Discount Programs made available through specific pharmacies and pharmaceutical companies (Towers, 2005). The APN may want to become familiar with the various options to explore with individual patients. An important component of this legislation is in the provision of direct reimbursement for serving in the capacity as primary provider for patients who are enrolled in the Medicare Hospice Benefit or in Medicare reimbursed skilled home care. Currently, NPs are not able to directly admit patients into hospice care (this requires two physicians who designate a limited prognosis of 6 months or less) or into the services of skilled home care. The NP, however, is able to seek reimbursement when providing services that reflect primary care management (Towers, 2005).

CONCLUSION

It is the APN who can provide the coordination and comprehensive care management that are often lacking for the patient and his or her family living with a chronic or life-limiting disease. APNs who provide services to adult patients can easily integrate their knowledge and skills into the assessment, management, and evaluation of symptoms that accompany advanced disease from diagnosis until death in multiple settings. Identifying and managing the multidimensional needs of the patient and family make the APN a unique professional on the health care delivery team who is able to collaborate with other providers, make appropriate referrals (psychosocial, spiritual, individual specialists), and engage the patient and family in meaningful conversations that include care options and modifications in advance care planning.

APNs who integrate palliative interventions throughout the trajectory of disease can help the patient and family to better understand prognostic indicators that may suggest a needed shift in care from curative to palliative in nature. It is this coordination of care and patient and family familiarity with the APNs that supports a reduction in a fragmented and less costly care delivery. Lack of coordination comes at a high cost, and it is in the delivery and the collection of palliative clinical outcomes that the APN can demonstrate value within the current reimbursement structure.

APNs have the potential to define, demonstrate, and differentiate their roles and influence patient outcomes when palliative care is utilized. Applying the best evidence and collecting important outcome data that identify patient quality of life through functional capabilities, reduction in symptom burden, access to supportive services, and cost effectiveness will make this provider a leader in the provision and practice of palliative care.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality National Guideline Clearinghouse

American Academy of Nurse Practitioners

American College of Nurse Practitioners

Federal Register rules and updates

National Association of Clinical Nurse Specialists

Nurse Practitioner Central

Reimbursement realities for advanced practice nurses

Allan, J., The nurse practitioner: A look at the future, In: (Editor: Stanley, J.) Advanced nursing practice2nd ed. ( 2005)Davis, Philadelphia, pp. xxviii–xxx.

American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, Medicare reimbursement fact sheet. ( 2004)Author, Office of Health Policy, Washington, DC; Retrieved May 14, 2006, from www.aanp.org.

American Nurses Association, A social policy statement. ( 1996)American Nurses Publishing, Washington, DC.

American Nurses Association, Scope and standards of advanced practice registered nursing. ( 1996)American Nurses Publishing, Washington, DC.

American Nurses Association, Government affairs—Summary of state legislation related to APRNs, Retrieved August 10, 2005, from www.nursingworld.org/member/gova/aprns05.cfm ( 2005).

American Nurses Credentialing Center, Frequently asked questions about ANCC certification, Retrieved August 18, 2005, from www.nursingworld.org/ancc/certification/certfaqs.html ( 2005).

Berry, P.; Kuebler, K., The advanced practice nurse in end-of-life care, In: (Editors: Kuebler, K.; Berry, P.; Heidrich, D.D.) End-of-life care clinical practice guidelines ( 2002)Saunders, Philadelphia, pp. 3–14.

Buppert, C., State regulation of nurse practitioner practice, In: (Editor: Buppert, C.) Nurse practitioner’s business practice & legal guide ( 1999)Aspen, Gaithersburg, Md., pp. 104–110.

Corner, J.; Clark, D.; Normand, C., Evaluating the work of the clinical nurse specialists in palliative care, Palliat Med 16 (2002) 275–277.

Corner, J.; Halliday, D.; Haviland, J.; et al., Exploring nursing outcomes for patients with advanced cancer following intervention by Macmillan specialist palliative care nurses, J Adv Nurs 41 (2003) 561–574.

Davis, L.; Gilliss, C., Primary care and advanced practice nursing: Past, present, and future, In: (Editors: Sheehy, C.M.; McCarthy, M.C.) Advanced practice nursing: Emphasizing common roles ( 1998)Davis, Philadelphia, pp. 114–136.

Davis, M.; Walsh, D.; LeGrand, S., End-of-life care: The death of palliative medicine [Editorial], J Palliat Med 5 (2002) 813–814.

Emanuel, L.; Alexander, C.; Arnold, R.M.; et al., Integrating palliative care into disease management guidelines, J Palliat Med 7 (2004) 774–783.

Emnettm, J.; Byock, I.; Twohig, J.S., Pioneering practices in palliative care. Publication produced by Promoting Excellence in End-of-Life Care, Retrieved July 26, 2005 from www.promotingexcellence.org/apn ( 2002).

English, N.; Yocum, C., Guidelines for curriculum development on end-of-life and palliative care in nursing education. ( 1998)National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization, Arlington, Va..

Hawkins, J.; Thibodeau, J., Advanced practice roles in nursing, In: (Editors: Hawkins, J.; Thibodeau, J.) The advanced practice nurse5th ed. ( 2000)Tiresias, New York, pp. 7–40.

Heitz, R.; Van Dinter, M., Developing a collaborative practice agreement, J Pediatr Health Care 14 (2000) 200–203.

Jack, B.; Oldham, J.; Williams, A., A stakeholder evaluation of the impact of the palliative care clinical nurse specialist upon doctors and nurses, within an acute hospital setting, Palliat Med 17 (2003) 283–288.

Kuebler, K., The palliative care advanced practice nurse, J Palliat Med 6 (2003) 707–714.

In: (Editors: Kuebler, K.; Moore, C.) The Michigan advanced practice nursing palliative care self-training modules ( 2002)Michigan Department of Community Health: Module Nine, Lansing, Mich..

Lyon, B.L., Clinical nurse specialists: Current challenges, In: (Editor: Stanley, J.) Advanced nursing practice2nd ed. ( 2005)Davis, Philadelphia, pp. xxv–xxviii.

Lysaught, J., Retrospect and prospect in joint practice, In: (Editor: Steel, J.) Issues in collaborative practice ( 1986)Grune & Stratton, Orlando, Fla., pp. 15–33.

Macmillan Cancer Support, Retrieved May 14, 2006, from www.macmillian.org.uk.

Mast, K.R.; Salama, M.; Silverman, G.K., End-of-life content in treatment guidelines for life-limiting diseases, J Palliat Med 7 (2004) 754–773.

National Association of Clinical Nurse Specialists (NACNS), Statement on clinical nurse specialist practice and education. ( 2004)Author, Harrisburg, Pa.; Retrieved May 14, 2006, from www.nacns.org.

National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care, National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care: Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care, executive summary, J Palliat Med 7 (2004) 611–617.

O’Connor, P.J., Adding value to evidence-based clinical guidelines, JAMA 294 (2005) 741–743.

Skilbeck, J.; Seymour, J., Meeting complex needs: An analysis of Macmillan nurses’ work with patients, Int J Palliat Nurs 8 (2002) 574–582.

Towers, J., In: Medicare Modernization Act (MMA): Are you utilizing its provisions? ( 2004)American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, Academy Update Office of Health Policy, Washington, DC, pp. 5–6; September.

Towers, J., In: National provider identifier implementation begins ( 2005)American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, Academy Update Office of Health Policy, Washington, DC, p. 8; June.

Venegoni, S.L., Healthcare delivery systems and environments of care, In: (Editors: Hickey, J.V.; Ouimette, R.M.; Venegoni, S.L.) Advanced practice nursing: Changing roles and clinical applications2nd ed. ( 2000)Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, pp. 151–174.

World Health Organization, In: Cancer pain relief and palliative care ( 1990)Author, Geneva, p. 804; Technical Report Series.

Yahoo Education, Definitions, Retrieved August 10, 2005, from http://education.yahoo.com/reference/dictionary/entry/protocol ( 2005).