Pharmacology and the Nursing Process in LPN Practice

Objectives

1. List how LPNs are involved in the five steps of the nursing process.

2. Identify subjective and objective data.

3. Discuss how LPNs use the nursing process in administering medications.

Key Terms

assessment (ă-SĔS-mĕnt, p. 2)

auscultation (ăw-skŭl-TĀ-shŭn, p. 3)

database (DĀT-ă-bās, p. 2)

diagnosis (dĭ-ăg-NŌ-sĭs, p. 4)

evaluation (ĭ-văl-ū-Ā-shŭn, p. 7)

implementation (ĭm-plĕ-mĕnTĀ-shŭn, p. 5)

inspection (ĭn-SPĔK-shŭn, p. 3)

nursing process (NŬR-sĭng PRŎ-sĕs, p. 1)

objective data (ŏb-JĔK-tĭv DĀT-ă, p. 3)

palpation (păl-PĀ-shŭn, p. 3)

percussion (pĕr-KŬ-shŭn, p. 3)

six “rights” of medication administration (mĕd-ĭ-KĀ-shŭn ăd-mĭn-ĭ-STRĀ-shŭn, p. 5)

subjective data (sŭb-JĔK-tĭv DĀT-ă, p. 3)

therapeutic effects (thĕr-ă-PŬ-tĭk, p. 8)

The LPN’s Tasks and the Nursing Process

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Edmunds/LPN/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Edmunds/LPN/

Licensed Practical or Vocational Nurses (LPNs/LVNs) play an important role in giving nursing care, and their responsibilities are predicted to grow. There are many factors that will increase the future demand for nurses: many more people are retiring, older people are living longer, chronic diseases are affecting more people, and the incidence of problems like obesity and dementia are increasing. At the same time, more registered nurses (RNs) are retiring and leaving the workforce and fewer RNs are being trained to replace them.

The LPNs/LVNs of the future will have more responsibility in this changed environment. More tasks of the RN will be delegated to the LPN/LVN. There will be a growing need for LPNs/LVNs in most places where health care is being offered. The patients in today’s hospitals are often very ill and require close attention. There may be many new types of technicians and technology to dispense unit-dose medications in large city hospitals, but in nursing homes or small community hospitals, there may be few nurses and little equipment. Nurses may copy medications orders from a patient’s chart and carry the medicine in paper souffle cups to the patient. LPN/LVNs will be increasingly employed in these areas. Caregivers and patients may come from different cultural backgrounds, and there may be co-workers from several different cultures. All these changes in the health care workplace may lead to stress, cultural conflicts, misinterpretation, or confusion unless these factors are recognized and addressed.

Although most LPNs/LVNs are familiar with the nursing process, it is likely there will be fewer RNs in the future, and LPNs/LVNs should understand clearly how to proceed in an organized way as they plan care for patients. LPNs/LVNs will find work in some of the most technically complex and challenging aspects of health care, as well as working in facilities both in the United States and abroad, where they may be the health care leader and there are no fancy machines, testing equipment, or treatment plans. LPNs/LVNs will learn to use the latest equipment to provide care or to calculate drug dosages with a paper and pencil.

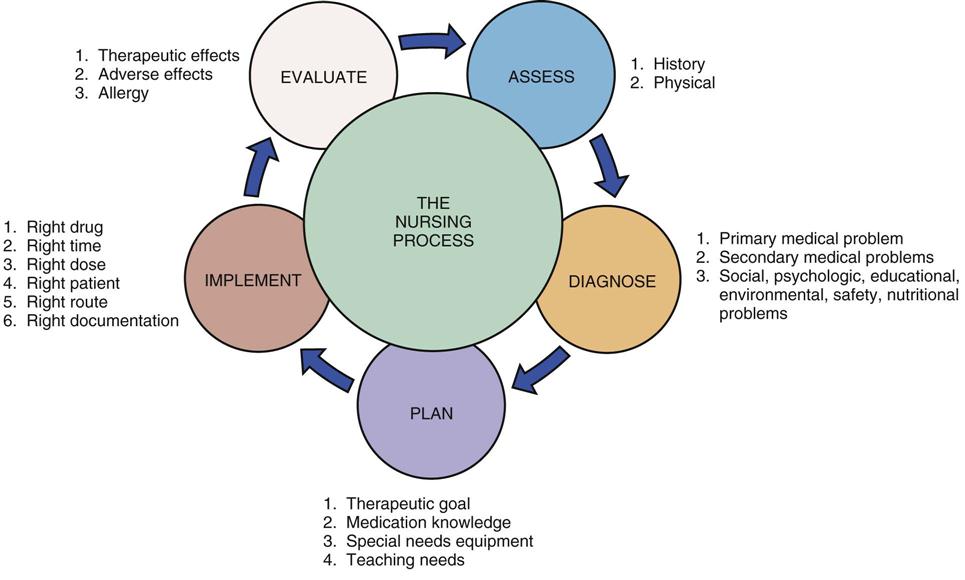

Nursing care is often complex. Nursing actions are specific behaviors that are carefully planned. The well-known process that helps guide the nurse’s work in logical steps is known as the nursing process. The nursing process consists of the following five major steps:

All of these steps are followed when you are giving medications to patients. The nursing process is shown in Figure 1-1.

RNs have both the knowledge and the authority they need to carry out all the steps of the nursing process. Their nursing actions do not require a legal order, so the RNs are acting independently. LPNs/LVNs do not have the same type of authority when they work with patients. Although LPNs/LVNs may need to rely on the RNs they work with in the planning and evaluation steps of the nursing process, they may be more independent as they collect data (assessment step) or help with the care of the patient (implementation step). For example, RNs interview the patient and do a physical examination of the patient, while LPNs/LVNs also learn information as they work with patients. It is usually the LPN/LVN who takes vital signs, checks response to medications and treatments, and monitors symptoms the patient is having. RNs and LPNs/LVNs work together to carry out medication or treatment orders written by health care providers. (Physicians are not the only ones who write orders. You may work with nurse practitioners, physician assistants, or other types of health care providers who may legally write orders.)

As you grow in the LPN/LVN role and gain experience, you will learn more complex skills that help with the nursing process. LPNs/LVNs are often given greater responsibility as they show they can do the work. In nursing homes and extended-care facilities, you may have opportunities to be a charge nurse and to manage patient care under the supervision of the RN. So it is important to master all parts of the nursing process. Experienced LPNs/LVNs will also assume more responsibility if no RN is directly available.

Assessment

An RN is legally assigned as the staff member who must perform the initial assessment for each patient. However, the LPN/LVN is often asked to assist with this task.

Assessment involves looking and listening carefully. It is a process that helps you get information about the patient, the patient’s problem, and anything that may influence the choice of drug to be given to the patient. This step of the nursing process is important because it gives you initial information as you begin to make a database, or record, from which all other nursing-process plans grow. Assessment means getting information by talking to the patient, looking at old records, or reviewing materials that the patient may bring. When the patient is admitted to the hospital, ask carefully about any current health problems, as well as any history of illnesses, surgery, and medications taken both now and in the past. This information is important for all team members to know and helps everyone plan the patient’s care. Information in the patient’s history often directs the nurse and the physician to look for certain physical signs of illness that may be present.

Information you gather through assessment falls into two groups: subjective data and objective data. Subjective data, or information given by the patient or family, includes the concerns or symptoms felt by the patient. Examples of subjective data include:

• The chief problem of the patient (in the patient’s own words)

• The detailed history of the present illness

• The medical history of the patient

• Social information: the patient’s job, education level, and cultural background

Some patient problems are more subjective than others. For example, if a patient reports pain in the abdomen, you must accept the patient’s word that the pain is present. The nurse cannot see, hear, or feel the patient’s abdominal pain—that is why it is subjective. A patient may state that he or she has trouble breathing. Although you may observe rapid breathing, the degree of difficulty cannot be measured. Information is subjective if you have to rely on the patient’s words or if the symptoms cannot be felt by anyone other than the patient. In such cases, you would report, “The patient states that. . . .”

Objective data is obtained when the health care provider gives the patient a physical examination. It also comes from documents that patients bring with them, such as old laboratory results, electrocardiogram (ECG) printouts, or x-rays, and from information you gather during the physical examination. Patients may even bring their medicines with them to the hospital or clinic. Objective data are gathered through assessment of vital signs (respiratory rate, pulse, blood pressure, weight, height, temperature); physical findings you can see during careful inspection (close observation), palpation (feeling), percussion (feeling differences in vibrations through the skin), and auscultation (listening with the stethoscope); and the results of recent laboratory tests and diagnostic procedures.

It is especially important to get subjective and objective assessment data when the patient is first seen or on admission to the hospital. This provides initial, or baseline, information that can be used to determine how ill the patient may be. Assessment is then done throughout the period of care to see if the patient is getting better with the treatment ordered.

The nurse may not always be the one gathering the subjective and objective data; however, the nurse and everyone else on the health care team should learn whatever information they can from the chart, the physician, the family, or other team members, and use that information to plan the patient’s care. Understanding the difference between subjective and objective information will help you in reporting, or charting, the information. For example, if the patient reports pain (subjective information), your notes should say, “The patient complains of pain” rather than “The patient has pain,” because you do not know if what the patient is feeling is actually pain or only discomfort. Much of your job in assessing will be reporting data you collect to the RN. As you learn more skills, or work in places such as nursing homes where you may have more responsibility, you will play a larger role in assessing the patient. How big a part you play in assessing the patient is defined by your state nurse practice act, which lists what LPNs/LVNs may and may not do.

Factors to Consider in Assessing the Patient

Certain information is very helpful in planning drug therapy. The nursing assessment at the time of the patient’s admission to the hospital should take special note of the drug history. You must talk to the patient, who is the first or primary source, but sometimes you also have to talk to a patient’s relatives or get old medical records, ECG results, or laboratory reports (secondary sources). Sometimes your nursing books or the Internet (tertiary sources) may also provide helpful information about a specific disease, medication, or procedure.

When asking about the patient’s drug history, the nurse makes assessments in the following areas:

2. Current (and sometimes past) use of all medications and drugs:

• All prescription medications (patients often forget to mention birth control pills in this category)

• Alcohol or street drugs used for recreational purposes (such as marijuana or cocaine)

• Alternative therapies such as herbal medicines or aromatherapy

You will also be assessing changes in patient condition or status that may influence drug therapy during the time the patient is in the hospital. This is how you will know if the medication is helping the patient or not.

Diagnosis

Once the assessment information has been collected, the LPN/LVN and other health care team members must make a diagnosis (a conclusion about the patient’s problem). The physician will decide the medical diagnoses. The RN will identify the nursing diagnoses. The hospital where you work may use the formal nursing diagnosis system developed by the North American Nursing Diagnosis Association–International that allows RNs to share a common language and a common way of describing a patient’s condition. However, many hospitals do not recognize or use this system. In either case, after talking to the patient, you will come to some decisions about how sick the patient is and how carefully you need to watch them. You will make your own decisions about some of the following questions:

• What procedures or medications will this patient require?

• What special knowledge or equipment is required in giving these medications?

• What special concerns or cultural beliefs does the patient have?

• How much does this patient understand about the treatment and medicine prescribed?

The answers to these questions will (1) help you set the goals of nursing care, (2) affect how closely you need to work with the patient, and (3) tell you what type of patient education will be needed. Getting accurate answers to these questions may be harder with children, older adult patients, or people whose language or culture is different from yours. However, just as a physician must have the correct diagnosis to prescribe the right treatment, the nurse must find the correct answers to these questions to be able to plan the best care for the patient.

Planning

Based on the data you help collect, the medical and nursing diagnoses are made, goals are set, and care plans are written. As a member of the health care team, the LPN/LVN will be able to assist with the planning step. As you help the RN plan the care for each patient, the plan will become easier to write. Nursing plans involve two groups of people: the nurses and the patients. Patient goals help the patient learn about a medication and how to use it properly. Nursing goals help the nurse plan what equipment or procedures are needed to give the medication. Using the information gathered in the assessment about the patient’s history, medical and social problems, risk factors, and how ill the patient may be, both types of plans can be prepared. The patient-focused care plan will include any medications that will be given on either a short-term or a long-term basis. For example, goals may be written regarding the application of ointments or patches or for showing the patient how to self-administer an aerosol nebulizer treatment. Nursing goals may include deciding how to rotate the injection site for drugs that require repeated injections (such as insulin), or teaching the patient about specific side effects of medications that might develop and when they should be reported.

As you write a list of the patient’s problems, you may find that problems are related. For example, a patient who cannot see very well may have a risk of tripping and falling in an unfamiliar hospital setting. The importance of problems may also shift as the patient’s condition changes. For this reason, what you do for the patient may change according to the patient’s changing needs.

Factors to Think About in Planning to Give a Medication

Planning to give a medication involves four steps:

2. Learn specific information about the medication:

• The desired action of the drug

• Side effects that may develop

• The usual dosage, route, and frequency

• Situations in which the drug should not be given (contraindications)

• Drug interactions (What is the influence of another drug given at the same time?)

3. Plan for special storage or procedures, techniques, or equipment needs.

4. Develop a teaching plan for the patient, including:

• What the patient needs to know about the medication’s action and side effects

• What the patient needs to know about the administration of the medication

The most important step in planning is to collect and use information about the patient (physical condition, cultural background, and expectations) and the medication. This step requires knowledge of the patient and the drug prescribed, plus your common sense and professional judgment.

In today’s hospitals and clinics, not only doctors order medications. Nurse practitioners, nurse midwives, nurse anesthetists, and physician assistants may all write some types of medication orders. Large hospitals may have a staff hospitalist—a physician who is always available in the hospital to oversee care for all patients. Teaching hospitals may have resident doctors who are still in educational programs. These individuals may write legal medication orders.

Once the medication is ordered, the nurse must verify that the order is accurate. This is usually done by checking the medication chart, medication card, medication administration record, or computer medication record with the original order. You will need to learn and follow the procedures of the agency where you work when checking medications. LPNs/LVNs will work in some of the most sophisticated health care settings with new equipment, computers, and many resources. They may also work in facilities in which there is no technology used, and following institutional procedures, the nurse will carry the medication on a tray, watch while the patient takes it, and then record this in the patient’s chart. No matter the process, this step of checking must be done each time the medication is given. In this way, errors resulting from changes can be avoided.

The nurse must also apply knowledge about the drug to the specific drug order to determine whether the drug and the dosage ordered seem correct. No part of the order or the reason for giving the medication should be unclear. Any questions about whether a drug is appropriate or safe for that patient should be answered before the medication is given. Use good judgment in carrying out the medication order. If you decide that (1) any part of the order is incorrect or unclear, (2) the patient’s condition would be made worse by the medication, (3) the physician may not have had all the information needed about the patient when drug therapy was planned, or (4) there has been a change in the patient’s condition and a question has arisen about whether the medication should be given, the medication should be withheld (not be given) until the question can be answered and the physician called. If you believe there is a problem with the medication order and the physician cannot be contacted or does not change the order under question, notify the charge nurse and the nursing supervisor as soon as possible. Most hospitals have clear policies about whom to contact, how to report this problem, and what to do next.

The planning step of the nursing process is also the time to do the following:

All this information can be written on the nursing care plan or in the Kardex file or entered into the computer so that other team members can see the plan.

Implementation

Implementation involves following the care plan and giving the medicine accurately to the patient. This step of the nursing process requires that the nurse use the information learned about each patient and about each drug ordered. It is your job to understand why each medication is ordered, to know about the drug’s actions, and to know how to safely administer it. For example, if you add an antibiotic solution to an IV line, you need to know about the proper equipment, aseptic technique, rate of flow, and reactions with the drugs already in the IV solution, as well as how to flush the line after therapy has ended. Implementation also may require you to do specific nursing tasks before giving the medication. For example, you will take the patient’s pulse before giving digitalis to make sure it may be given safely. Implementation also means that you will watch for any changes in the patient’s condition that may make it unwise to give the medication. For example, if a patient receiving antibiotics says she has an itchy rash on her chest and arms, you will withhold the next dose of the antibiotic until you have called the patient’s physician to report the rash. Once the medication is given, this needs to be recorded in the patient’s chart.

There are six “rights” of medication administration the nurse must always keep in mind. You must give the right drug, at the right time, in the right dose, to the right patient, by the right route, and use the right documentation to record that the dose has been given.

The Right Drug

The Right Drug

Many drug names are hard to remember and difficult to read. Also, many drugs have names that sound or look nearly the same as the names of other drugs. It is important to carefully check the spelling of the name and the dose of each medication before any drug is given. For example, NovoLog and Novolin are both insulin products used for diabetics, but they are quite different in dosage and duration of action. It is also easy to get confused when a medication is ordered by a trade name (such as Valium), but the pharmacy sends up the medication labeled with the generic name (diazepam). Do not assume that the correct medication has been sent without checking a reliable source or calling the pharmacy.

The drug may come in a unit-dose-system package, locked cabinet for the patient, as a prescription filled for one person, or the medication may be taken from a unit’s stock. Sometimes the medication dose has a barcode that is scanned by a computer. However it comes, you must read the drug label at least three times:

The Right Time

The Right Time

The drug order should say when the medication is to be given. Hospitals have policies that tell you what time drugs will be given when they are ordered (such as “every 4 hours”). You must be familiar with hospital policy and use only standard abbreviations in recording the drugs given (see Chapter 3 for information on standard abbreviations). To be effective, many drugs must be given exactly on schedule day and night to keep the level of medication constant in the body. Other medications may only need to be given during the day.

You will also need to plan around other patient activities when you give medications. For example, if a patient is taking an anticoagulant to thin the blood and decrease the risk of blood clots, the medication must be given at the same time every day. Patients with infections need to have specimens taken for culture before starting antibiotic therapy. Patients undergoing evaluation of thyroid function need to have blood tests for those functions done before having gallbladder x-ray studies, which involve the use of chemicals that may confuse thyroid function study results or make them inaccurate.

Medications are usually given when there is the best chance for the body to absorb it and the least risk for side effects. This may mean that some medications should be given when the patient’s stomach is empty, and others should be given with food. Some medications require that the patient not eat certain foods. Others do not mix well with alcohol. When a patient is taking several medications, check to make sure the drugs do not interfere with each other. (For example, some antibiotics interfere with the action of birth control pills, so a woman taking both could get pregnant if she does not use another form of contraception.)

Finally, one-time-only, as-needed (prn), or emergency medications are especially important to check. The nurse must be certain that no one else has already given the medication or that it is the appropriate time to give the drug. Narcotics are often ordered as “stat” (given within a few minutes of the order) or prn medications. Note on the patient’s record as soon as possible that you have given a narcotic so that it is clear the patient has been given the medication.

Box 1-1 lists the main factors to remember in giving medication at the right time.

The Right Dose

The Right Dose

The amount of medicine to be given is usually ordered for the “average” patient. A patient who is old, who has severe weight loss as a result of illness, or who is small or very obese may require changes in the usual dosages. Pediatric patients have doses ordered depending on how much they weigh. Geriatric, or older adult, patients may be very sensitive to many medications and may require a change in dosage. If patients have other diseases or poor liver or kidney function, this may make changes in dosage necessary. Patients who have nausea or vomiting may be unable to take oral medications. Also, the physician may order the correct dosage of the medication when treatment begins, but changes in the patient’s condition may require that you go back to the physician to have the dose altered.

Giving the correct dosage of a medication also requires that you use the proper equipment (for example, insulin must be measured in an insulin syringe), the proper drug form (oral or rectal, water or oil base, scored tablets or coated capsules), and the proper concentration (0.25 mg or 2.5 mg) and that you accurately calculate the right drug dosage. Most hospitals and clinics have rules that require two nurses to check any medication dosage that must be calculated, particularly for medications such as narcotics, heparin, insulin, or IV medications.

The Right Patient

The Right Patient

Typically, hospital procedure requires that we ask the patient for their name and birth date and also confirm their identify by examining the wrist band. Although it seems like common sense to make certain the right patient gets the medication, errors may occur on a busy hospital unit. Several groups of patients are most at risk for errors: the pediatric patient, the geriatric patient, the non–English-speaking patient, and the very confused or critically ill patient. The common factor among these four groups is that it might be hard for them to tell the nurse who they are. They also may not understand what you are asking or that a drug is being given to them. The identification bracelets (name bands) that some patients wear may have been removed for tests or when blood was drawn. Be especially careful with children, because they enjoy hiding, changing beds, answering to another name, and so on. Ask for the name as you check the patient’s identification bracelet or scan their name tag to confirm it is the correct patient. In a hospital, medications should never be given to a patient who is not wearing an identification bracelet. Nursing homes may present a special challenge for a nurse who does not know the patients well, because these patients may not wear identification bracelets, and they may be confused or unable to answer to their name. When available, the use of computers to scan the patient’s identification bracelet and the drug itself are helpful in making sure the correct patient gets the drug.

The Right Route

The Right Route

The drug order should state how the drug should be given (route of drug administration). The nurse must never change routes without getting a new order. Although many drugs may be given by different routes, the dose is often different for each route.

The oral route is the preferred route if the patient is oriented (awake and able to understand). In some cases, faster delivery or a higher blood level of a drug is needed, so the medication may be given intravenously or intramuscularly. There may be special precautions for medications given through these routes (such as how fast they can be given or in what dosage). Some injections should be given into the subcutaneous tissue rather than intramuscularly. Because of these differences, you need to know how to give an injection in several different places on the body. Also, some drugs are very painful if given intramuscularly, so giving them intravenously is preferable.

When drugs to help breathing are ordered, you need to find out whether the aerosol nebulizer is to be used through the nose or the mouth. Teach the patient the correct way to use the nebulizer so that the medication goes all the way into the lungs. Teach patients how to correctly use their eye drops, eardrops, ointments, lotions, shampoos, and rectal or vaginal medications.

The Right Documentation (Record Keeping)

The Right Documentation (Record Keeping)

Increasingly, electronic charting systems are being introduced into medical settings. Whether the nurse records medication administration and patient observations by hand or using an electronic chart, the basics are the same. A note about how and when you gave the drug should be made on the patient’s chart as soon as possible after the drug is given. In an emergency or when a drug is only used once or twice, this is very important. Rules at your agency may require that the chart note of intramuscular medications also include where on the body you gave the injection and any complaints made by the patient at the time of the injection. The chart note should always list the drug given, the dose, and the time it was actually given (not the time it was supposed to be given). In some offices or clinics where immunizations are given, the policy may require that the lot number listed on the bottle be recorded in the patient’s chart. Progress notes should include a note about the patient’s response to the medication. Any complaints or adverse effects should be noted in the chart and reported to the head nurse and the physician. When you make notes in the patient’s chart about medications, never record medications that were not given or record them before they are given. If a patient does not receive the medication, for any reason, notify the nurse in charge or the person who wrote the order.

It must be stressed that you must never give medication prepared by another nurse. Even when you are very busy, when there is an emergency, or when you are interrupted, you cannot assume that all the “rights” are followed unless the person who prepares the medication is the one who gives the medication. Sometimes a physician will ask you to prepare the medication for the physician to give. You may then prepare the medication, but go with the physician to see that the medication is given as ordered and write in the notes that the physician gave the medication.

Following the rules of your hospital, using common sense, and being accurate and ethical will reduce the risk of medication error. Should an error be made, talking about it honestly and taking quick action to correct any damage are especially important to protect the patient from harm.

Evaluation

Evaluation is the process of looking at what happens when the care plan is put into action. Evaluation requires the nurse to watch for the patient’s response to a drug, noting both expected and unexpected findings. When antipyretic medications (drugs that reduce fever) are given, take the patient’s temperature to see if the medication lowered the fever. When medications are given to make the patient’s heartbeat more regular, taking the pulse will help show how the patient responded to the medication.

Evaluation of what happens when you administer a drug helps the health care team decide whether to continue the same drug or make a change. Gathering such information is also a part of the continuing assessment of a patient during care that the nurse will record in the patient’s chart. Thus the nursing process may be seen as a circle (see Figure 1-1). For example, taking the patient’s temperature is part of the evaluation step of the nursing process, but it may also be part of the assessment step when you notice that the patient’s temperature is still high, indicating the patient needs more medication, a cooling bath, or some other treatment.

Factors to Think About in Evaluating Response to Medication

The nurse checks for two types of responses to drug therapy: therapeutic effects and adverse effects.

Therapeutic effects are seen when the drug does what it was supposed to do. If you understand why the medication is being given (the therapeutic goal of the drug), you will be able to decide whether or not that goal is being met. For example, if the patient’s blood glucose is high and regular insulin is given, you should see a lower blood glucose level when the test is repeated in 1 to 2 hours.

Adverse or side effects are seen when patients do not respond to their medications in the way they should or develop new signs or symptoms. For example, a patient with pneumonia may be given penicillin. Although this antibiotic may be working to control the infection, the patient may develop shortness of breath, which may be an allergic reaction to the medicine, and the penicillin must be stopped. A patient getting an anticoagulant to thin the blood must be closely watched for signs of bleeding or bruising that would indicate overdosage or overresponse to the medication. Sometimes, side effects such as nausea or vomiting may be stopped by decreasing the dosage or by giving the medication with food. Telling the physician about whether the side effects are mild or severe helps the physician decide whether the patient should keep taking the drug or it should be stopped.

The nurse is the health care worker most often with the patient and is in an important position to notice the patient’s response to drug therapy. Carefully and repeatedly evaluating the patient and writing down the findings in the patient’s chart are especially important in the care of the hospitalized patient.