CHAPTER 1 From Neurons to Acupoints: Basic Neuroanatomy of Acupoints

INTRODUCTION

The efficiency of acupuncture therapy is based on the selection of effective acupoints. There are 361 classic meridian acupoints, and more than 2000 new extrameridian acupoints have been recorded in the Chinese literature on acupuncture. Anatomic examination of the 361 classic meridian acupoints shows that most acupoints are associated with certain anatomic structures of the peripheral nervous system (PNS). Researchers have indicated that 309 acupoints lie on or near the nerves and that 286 acupoints are situated next to major blood vessels, which are surrounded by small nerve bundles.1

Modern neuromuscular medicine named some of these points trigger points, motor points, and dermopoints. Dr. Ronald Melzack2 found that more than 70% of the classic meridian acupoints correspond to commonly used trigger points. Whatever terms are used, all these points are characterized by the ability to become painful or tender or to create other physical discomforts as a result of sensitized nerves. It is extremely important to understand that although more than 70% of the classic acupoints share the same characteristics as trigger points, acupoints and trigger points are not the same.

In their book Muscle Pain, Drs. Siegfried Mense and David G. Simons define trigger points as follows: “(1) A central trigger point is a tender, localized hardening in a skeletal muscle. Clinical characteristics include circumscribed spot tenderness in a nodule that is part of a palpably tense band of muscle fibers, patient recognition of the pain evoked by pressure on the tender spot as being familiar, pain referred in the pattern characteristic of trigger points in that muscle, a local twitch response, painful limitation of the stretch range of motion, and some weakness of that muscle. Diagnostic criteria of active trigger points are circumscribed spot tenderness in a nodule of a palpable taut band and patient recognition of the pain, evoked by pressure on the tender spot, as being familiar. Latent trigger points cause no complaint of clinical pain. (2) Attachment trigger points have tenderness in the region of muscle attachment caused by enthesitis or enthesopathy induced by the persistent tension of the taut band muscle fibers.”3

In laboratory and clinical experiments, acupuncture stops being effective in a region supplied by a sensory nerve when that nerve is blocked by local anesthesia, cut by surgery, numbed by ice (low temperature), or bound by a band.4 These experiments prove that sensory nerves are vital anatomic components of acupoints. Sensory nerves are distributed all over the human body and are absent on only a few structures, such as nails and hair. Thus where there are sensory nerves there will be acupoints.

The Chinese doctors of ancient times noticed that, in addition to meridian acupoints, some nonmeridian acupoints are as effective as classic meridian points. The two types of nonmeridian acupoints are Ashi acupoints and extrameridian acupoints. Ashi acupoints appear unpredictably in relation to individual symptoms. Extrameridian acupoints are not located on any of the 14 meridians but have fixed locations on the body. Gradually more and more extrameridian acupoints were recorded and incorporated into the classic acupuncture system. The recent Chinese acupuncture literature has recorded more than 2500 “new” acupoints.

In the last three decades, an impressive number of modern studies show that acupuncture efficacy does not always depend on the precise location of acupoints as indicated on meridian charts.5 Scientific data suggest that there is no statistical significance between needling either “sham” or “true” acupoints in treating patients with chronic pain.6 Well-known clinician Dr. Felix Mann, after many years of observation, has concluded that acupoints, in the classic understanding, do not exist at all.7

Tender acupoints appear on the bodies of both healthy persons and pain patients alike. Let us look at a healthy person first. Dr. H.C. Dung discovered that tender acupoints appear in a generally consistent and predictable pattern. Dr. Dung provided an anatomic explanation for why acupoints appear in such a predictable pattern (see Chapter 2). This discovery is regarded as “a turning point in acupuncture’s long history.”8

BASIC NEUROANATOMY FOR DEFINING ACUPOINTS

Neuron (Nerve Cell)

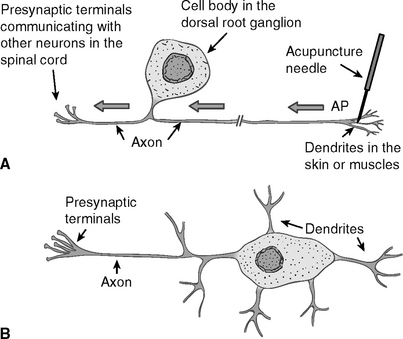

A neuron, or nerve cell, is the anatomic and physiologic unit of the nervous system. Neurons vary in size, shape, and complexity (Figure 1-1). All neurons share common structural and functional features. Typically a neuron has one or more processes, called dendrites, radiating from the cell body. The endings of the dendrites are called receptors.

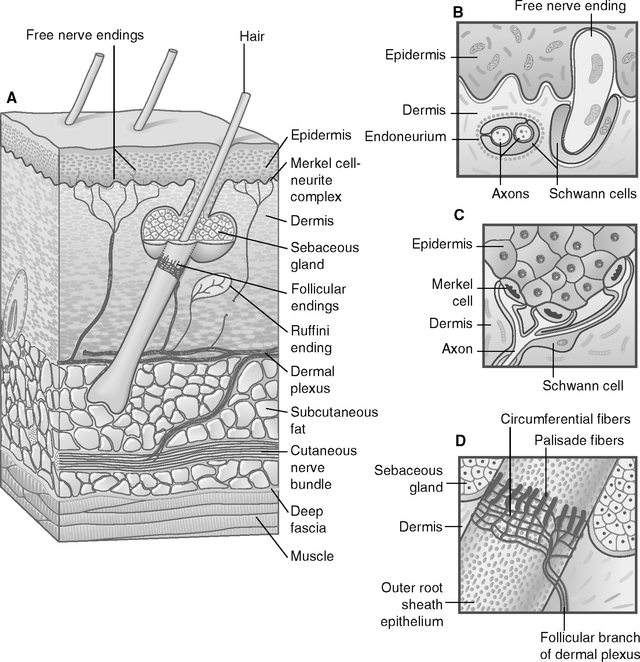

Acupuncture needles directly stimulate and activate the dendrite receptors of the sensory neurons in the skin, muscles, and other soft tissues. Figure 1-2 shows some of the sensory nerve endings (receptors), such as free nerve endings and encapsulated nerve endings.

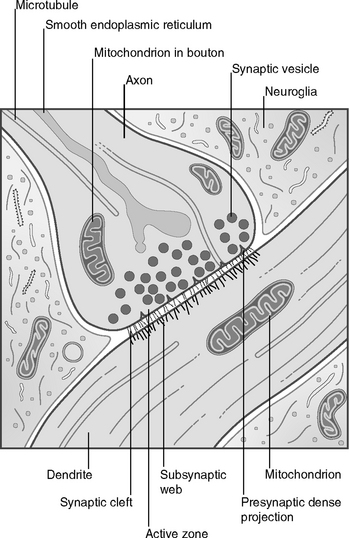

Another single process, called an axon, extends from the cell body (see Figure 1-1). An axon of a sensory neuron sends the impulses from the cell body to the next neuron, or an axon of a motoneuron brings the impulses to the muscles. Stimulation of the receptors by acupuncture needling generates electrical signals, which travel from receptors along the dendrites to the cell body and then to the axon. Stimulation below the threshold will not generate incoming signals to the brain. When stimulation to the receptors is strong enough, it will initiate in the cell body a transient electrical signal called an action potential, which will propagate from the cell body along the axon to the axon terminal. The axon terminal passes the signals to the dendrites or cell body or axon of another neuron through a special structure called a synapse. Thus signals generated by receptors are transmitted from one neuron to another neuron and finally reach the brain (Figure 1-3).

The Central Nervous System

A neuron is a major functional unit in the nervous system. The CNS consists of the brain and the spinal cord. Electrophysiologic9 and neurochemical research shows that both the brain and the spinal cord actively react to acupuncture stimulation. Today, after more than three decades of research, we know more about the involvement of the CNS in acupuncture therapy, but the exact mechanism of this correlation is still unclear. We briefly discuss this mechanism in Chapters 3 and 4.

The Peripheral Nervous System

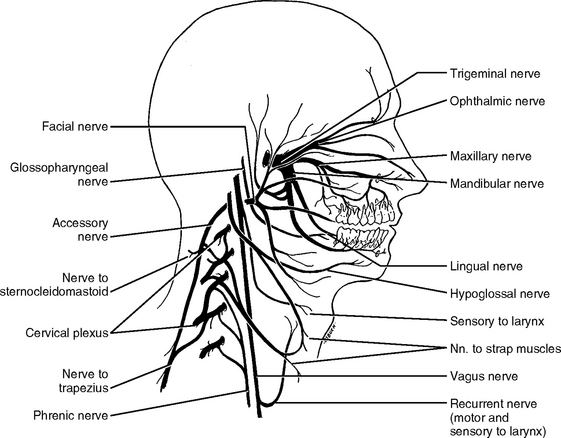

The PNS consists of the cranial nerves from the brain and the spinal nerves from the spinal cord, a total of 12 pairs of cranial nerves and 33 pairs of spinal nerves. Traditionally Roman numerals are used to designate the cranial nerves. Among them, the trigeminal nerve (V), facial nerve (VII), and spinal accessory nerve (XI) are the most important in acupuncture therapy (Figure 1-4).

Figure 1-4 The cranial nerves accessible by acupuncture needling in the head and neck: trigeminal nerve (V, three branches: ophthalmic, maxillary, and mandibular), facial nerve (VII), and accessory nerve (XI). Also note that, activated by acupuncture stimulation, the vagus nerve plays a very important role in restoring homeostasis and antiinflammatory immune reaction (see Chapter 4 for further explanation).

(From Jenkins D: Hollinshead’s functional anatomy of the limbs and back, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2002, WB Saunders.)

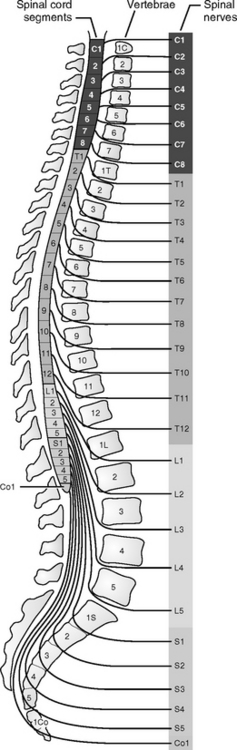

According to their location in relation to the spinal cord, the 33 pairs of spinal nerves are categorized into five groups: 8 cervical, 12 thoracic, 5 lumbar, 5 sacral, and 3 coccygeal. The coccygeal nerves are less important in acupuncture because of their relatively small size, although severe pain in the coccyx or tailbone may occur and will need to be attended (Figure 1-5).

Figure 1-5 The spinal nerves that make up most of the peripheral nerves of the body.

(From Jenkins D: Hollinshead’s functional anatomy of the limbs and back, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2002, WB Saunders.)

The PNS also contains ganglions, which are groups of nerve cells outside the spinal cord. The nerve fibers of the PNS are distributed to all areas of our body except the nails or hair, which is why nails and hair can be cut without pain.

Somatic Nervous System

We classify the nervous system into the CNS and the PNS according to anatomic structure. Functionally we divide the nervous system into two groups: the SNS and the ANS. The SNS is the part of the nervous system that innervates the structures of the body wall: muscles, skin, and mucous membranes. The part of the nervous system that controls visceral organs is referred to as the ANS. From the viewpoint of acupuncture therapy, the SNS is similar to parts of the PNS.

Autonomic (Visceral) Nervous System

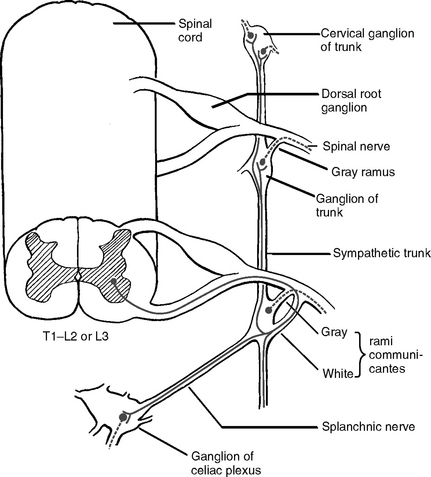

Anatomically the efferent components, the outflow pathway of the ANS, are characterized by a two-neuron chain (Figure 1-6). The first neurons, or the primary neurons, are located in the CNS in the brainstem nuclei (groups of neurons in the brain are called nuclei) or in the lateral gray column of the spinal cord.

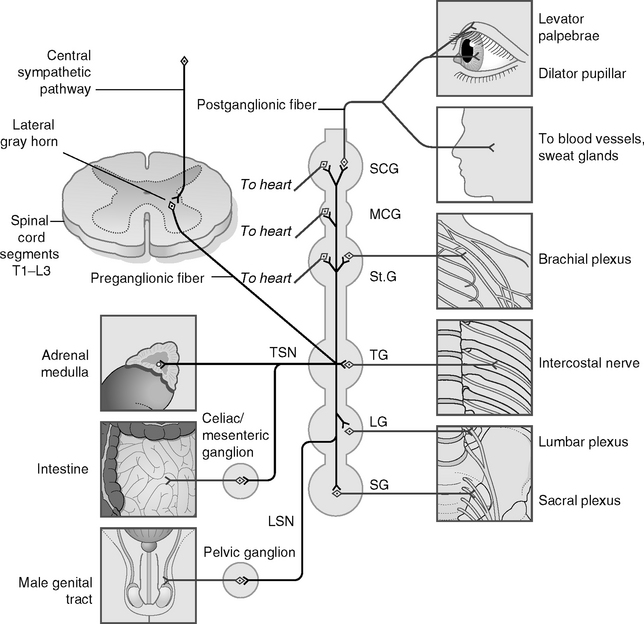

Functionally the ANS is further subdivided into two divisions: sympathetic and parasympathetic. The sympathetic (thoracolumbar) division (Figure 1-7) originates from neurons (preganglionic neurons) in the spinal cord (C8-L2).

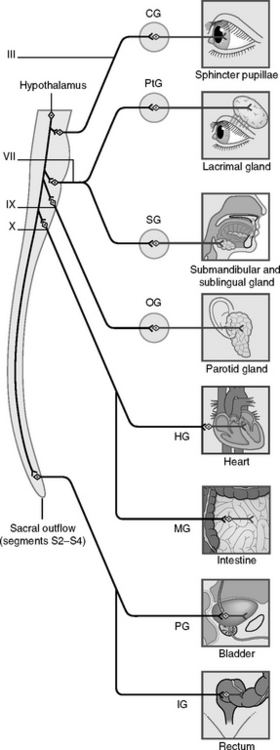

The parasympathetic (craniosacral) division (Figure 1-8) comprises preganglionic neurons in the gray matter of the brainstem and of the middle three segments of the sacral cord (S2-4).

When the sympathetic nervous system calms during rest and a period of tranquility, the parasympathetic system becomes active. The decreasing hyperactivity of the sympathetic system ensures, for example, such functions as proper food digestion, which helps to absorb and supply energy flow to the body systems.

Nerves and Nerve Fibers

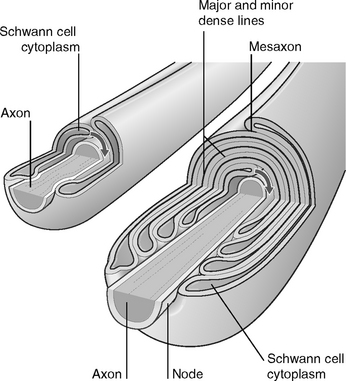

Different signals can travel in different directions in the same nerve. To ensure that the delivery of the functional signaling reaches the exact address, something must function like an insulating tube to cover a dendrite or axon to protect the signals. Schwann cells provide this insulating layer, called a myelin sheath (Figure 1-9).

Figure 1-9 Schwann cell and myelination in peripheral nervous system.

(From FitzGerald M, Folan-Curran J: Clinical neuroanatomy and related neuroscience, ed 4, Philadelphia, 2002, WB Saunders.)

Efferent (Motor) Nerves

The three types of muscles are skeletal, smooth, and cardiac. In the face and head, the efferent fibers arise from the brain and innervate the muscles of mastication and the muscles of facial expression by the trigeminal nerve (V) and the facial nerve (VII), respectively. The skeletal muscles situated all over the body are innervated by the efferent fibers. The efferent fibers originate from the motor nerve cells in the anterior horn of the spinal cord. Smooth muscles innervated by autonomic nerve fibers are found in the blood vessels and in all visceral organs. Cardiac muscles are heart muscles that are innervated by autonomic nerve fibers. It is important to understand how the three types of muscles function during an acupuncture treatment.

Afferent Fibers and Sensory Receptors

Physiologically the four types of sensations are superficial, deep, visceral, and special. Superficial sensation is pain, touch, temperature, and two-point discrimination (i.e., the shortest distance between two stimuli our brain can recognize as two points). Deep sensation is related to deep muscle pain, muscle and joint position sense (proprioception), and vibration sense. Visceral sensations are relayed by autonomic afferent fibers, including visceral pain, hunger, and nausea. Special sensations are smell, vision, hearing, taste, and equilibrium, which are transmitted by certain cranial nerves.

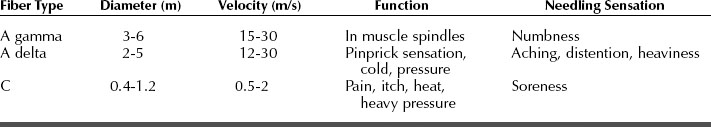

The Nerve Bundles

Note that the electrical signals travel faster along thicker nerve fibers. The skin is innervated with three types of sensory fibers: A beta, A delta, and C fibers. A beta fibers are sensitive to gentle pressure and vibration, the thinner A delta fibers are sensitive to heavy pressure and temperature, and the very thin and unmyelinated C fibers are responsive to pressure, chemicals, and temperature. When needles are inserted into the skin or muscle tissue, they stimulate the two finest fibers: A delta fibers and C fibers. A small electrical stimulus, such as that used in transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), preferentially excites the large A beta fibers. The physiology of these fibers is summarized in Table 1-1.

Anatomic Configuration of Acupoints

At present the exact anatomic identity of acupoints has not been clearly established. After careful clinical observation and meticulous laboratory research, Dr. H.C. Dung suggested 10 anatomic features associated with acupoints.10 Each acupoint may contain one or more of these features.

TEN BASIC ANATOMIC FEATURES OF ACUPOINTS

2. Depth of the Nerve

The superficial acupoints become tender more often than do the deeply located acupoints because of the abundant assemblage of sensory receptors around the location where the acupoints are formed. An interesting neurologic fact is that the limbs below the elbows and knees occupy larger areas in the sensory gyrus in the brain. Therefore the acupoints below the elbows and knees also occupy a larger area in the cortical representation in the postcentral sensory gyrus in the brain. This may explain why the acupoints below the elbows and knees contain more sensory receptors and why needling stimulation to these points may induce a greater reaction and activity in the brain. This principle clearly supports the concept of using certain acupoints below the elbows and knees (the so-called five-Shu points in the classic meridian system) as diagnostic and treatment points during acupuncture treatment.

4. Passage Through Bone Foramina

Acupoints are found at the bone foramina, where nerve trunks emerge to distribute cutaneously. The cutaneous branches of the trigeminal nerves (V) give rise to such acupoints at the foramina as the infraorbital (H19, V2), the supraorbital (H23, V1), and the mental (V3) nerves (see Figure 5-2, p. 58).

7. Nerve Fiber Composition

The afferent (sensory) fibers provide sensory receptors attached to the blood vessels, muscle fibers, muscle spindles, muscle tendons, and skin. The sensory fibers collect sensory information from all these structures.

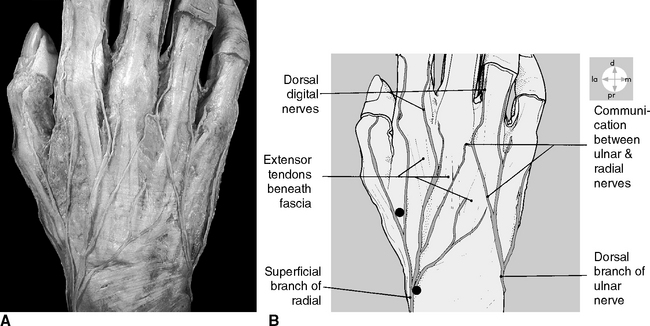

8. Bifurcation Points

Acupoints are found at locations where a large nerve trunk branches into two or more smaller branches. For example, acupoints are found in the distal portion of four limbs, particularly in the dorsal surfaces of the hand and foot (Figure 1-10).

10. Suture Lines of the Skull

Acupoints are formed along the suture lines of the skull. The acupoints can be palpated along the coronal suture, sagittal suture, and lambdoidal suture (see Figure 5-2, p. 58). Such acupoints appear at the nasion, fontanelle, bregma, pterion, and so on. When chronic headache is not adequately treated, eventually tender points will appear at these locations.

SUMMARY

The basic 10 neuroanatomic features of acupoints provide a solid foundation for understanding the nature of acupoint structural formation, their pathophysiologic dynamics, and their clinical meaning in evaluation and point selection during treatment procedures using our Integrative Neuromuscular Acupoint System (INMAS) (see Chapter 5).

Other structures could also contribute to the formation of acupoints. Japanese researchers, for example, suggested a close association of some acupoints with lymphatic channels.11

Each acupoint can have one or more of the 10 basic anatomic features. As discussed previously the 10 anatomic features are set forth in numeric order based on the anatomic features of the acupoints. Acupoints with an anatomic feature having a lower number in the order (such as feature 1, the size of the nerve trunk) usually become tender earlier than do acupoints with an anatomic feature having a higher number in the order (such as feature 10, suture lines of the skull).

The preceding pathophysiologic and clinical phenomena play important roles in our INMAS for pain management and serve as a foundation for our quantitative evaluation and prognostic prediction method described in Chapter 6.

The basic 10 features of acupoints provide the following:

The tenderness of acupoints arises from pathological conditions affecting either peripheral or central nerve fibers. Peripherally the sensory nerve fibers could be sensitized by the chemicals leaked from the damaged tissues to form the tender points. Centrally the neurons in the spinal cord can become sensitized by lasting stimulation of nerve impulses from peripheral receptors, such as in the case of chronic pain or cumulative trauma disorders (repetitive use of the same muscles).12

From a neuroanatomic perspective the features of acupoints could be summarized in the following way:

The pathophysiologic quality of each acupoint (the sensitivity and size of tenderness) and the clinical quantity of acupoints (the total number of tender acupoints in a person) provide indispensable information for our quantitative evaluation and prognosis method described in Chapter 6 and serve as a foundation for our Integrative Neuromuscular Acupoint System for pain management, also described in Chapter 6.

1 Chan SH. What is being stimulated in acupuncture evaluation of the existence of a specific substrate. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1984;8:25-33.

2 Melzack R, Stillwell DM, Fox EJ. Trigger points and acupuncture points for pain: correlations and implications. Pain. 1977;3:3-23.

3 Mense S, Simons DG. Muscle pain, understanding the nature, diagnosis, and treatment. Philadelphia: Lippincott–Williams & Wilkins, 2001.

4 Chiang CY, et al. Peripheral afferent pathway for acupuncture analgesia. Scientia Sinica. 1973;16:210-217.

5 Taube HA, et al. Studies of acupuncture for operative dentistry. J Am Dent Assoc. 1977;95:555-561.

6 Pomeranz B. Acupuncture analgesia: basic research. In: Stux G, Hammerschlag R, editors. Clinical acupuncture scientific basis. Berlin: Springer, 2001.

7 Mann F. A new system of acupuncture. In: Filshie J, White A, editors. Medical acupuncture. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1998.

8 Macdonald AJR. Acupuncture’s non-segmental analgesic effects: the point of meridians. In: Filshie J, White A, editors. Medical acupuncture. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1998.

9 Ma Y-T, Sluka KA. Reduction in inflammation-induced sensitization of dorsal horn neurons by transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation in anesthetized rats. Exp Brain Res. 2001;137:94-102.

10 Dung HC. Anatomical features contributing to the formation of acupuncture points. Am J Acupuncture. 1984;12:139.

11 Iguchi K, Sawai Y: Correlationship between the meridians and acute lymphangitis. In Proceedings of the 3rd World Conference on Acupuncture, Kyoto, 1993.

12 Wall P. Pain: the science of suffering. New York: Columbia University Press, 2000.