Procedure 1 Examination of the Hand and Wrist

![]() See Video 1: Clinical Examination of the Hand and Wrist

See Video 1: Clinical Examination of the Hand and Wrist

Figures 1-42 and 1-43 are from Chung KC, Yang L, McGillicuddy JE (eds). Practical Management of Pediatric and Adult Brachial Plexus Palsies. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2011.

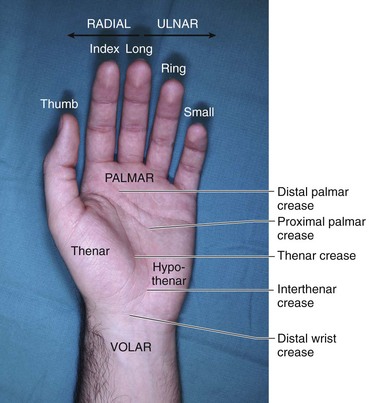

The human hand consists of a broad palm with five digits, attached to the forearm at the wrist joint. The five digits include the thumb and the four fingers, namely the index (IF), long (LF), ring (RF), and small finger (SF) (Fig. 1-1). The long and small fingers are often called the middle and little fingers, respectively. We believe that the term long finger is more appropriate to avoid the ambiguity as to what constitutes the middle finger. The use of little finger and long finger confuses their acronyms (LF); hence, small finger is preferred.

The hand has two surfaces—dorsal and palmar. The use of the term palmar should be restricted to the area limited by the glabrous skin, and the term volar should be used for areas proximal to it (see Fig. 1-1). Radial is used to describe direction toward the thumb and ulnar to describe direction toward the small finger, rather than lateral and medial (see Fig. 1-1). The palm has two eminences: the thenar eminence, which contains the intrinsic muscles of the thumb; and the hypothenar eminence, which contains the intrinsic muscles of the small finger (see Fig. 1-1). The connotation of the word intrinsic is to describe muscles that originate and insert in the hand, whereas extrinsic indicates muscles that originate outside the hand, such as the extrinsic finger flexors. The three well-defined creases of the hand are the thenar crease (forms the boundary of the thenar eminence), the proximal and distal palmar creases, and the distal wrist crease (forms the boundary of the glabrous skin) (see Fig. 1-1).

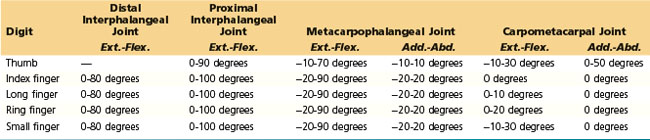

Each finger has three phalanges, namely proximal, middle, and distal, and three joints, namely metacarpophalangeal (MCP), proximal interphalangeal (PIP), and distal interphalangeal (DIP). The thumb has two phalanges, proximal and distal, and two joints, the MCP and the interphalangeal (IP). There are five metacarpals and five corresponding carpometacarpal (CMC) joints, which are numbered I to V from radial to ulnar. The first CMC joint is also known as the thumb basal joint (Fig. 1-2).

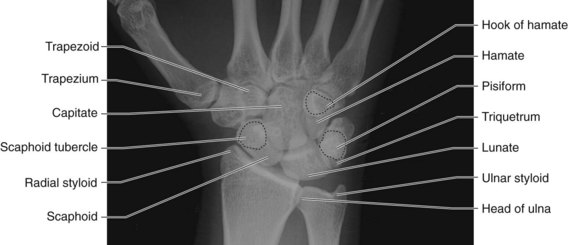

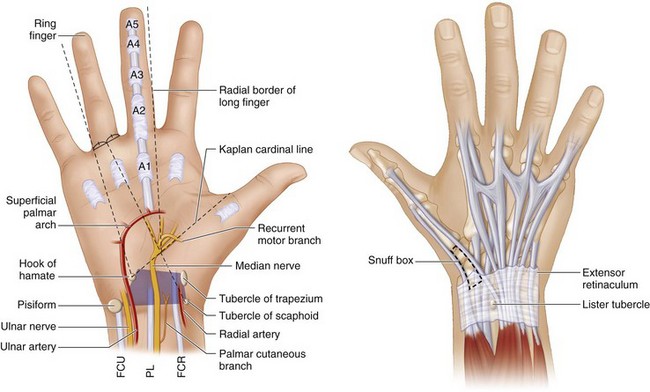

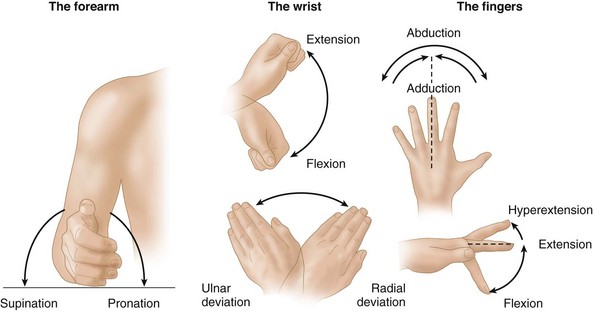

There are eight carpal bones arranged in roughly two rows. From radial to ulnar, the proximal row has the scaphoid, lunate, triquetrum, and pisiform, and the distal row has the trapezium, trapezoid, capitate, and hamate (Fig. 1-3). The bones of the distal row form the CMC joint with the base of the metacarpals and the midcarpal joint with the carpal bones of the proximal row. The proximal row articulates with the radius and the ulna. The palpable bony landmarks of the hand and wrist and their relation to the surrounding structures are depicted in Figure 1-4. The correct terminology to use when describing motion at the different joints of the hand is illustrated in Figure 1-5.

Examination/Imaging

Position

Procedure

We conduct our examination in stages (Table 1-1). In the first stage, we do a primary survey and focus on the hand as a whole, examining both hands. This stage begins by listening to the patient’s complaints and obtaining relevant history. This is followed by the basic examination strategy of look (inspection), feel (palpation), and move (range of motion).

We conduct our examination in stages (Table 1-1). In the first stage, we do a primary survey and focus on the hand as a whole, examining both hands. This stage begins by listening to the patient’s complaints and obtaining relevant history. This is followed by the basic examination strategy of look (inspection), feel (palpation), and move (range of motion).

The second stage is a more focused examination of one or more specific systems limited to the involved hand. The system to be examined is derived based on the primary survey. At the completion of the secondary survey, we should have a preliminary diagnosis or a differential diagnosis. If a diagnosis is not apparent, one should not make up a nebulous diagnosis such as tendinitis or arthritis. These made-up diagnoses may satisfy the patient’s need to have a reason for the discomfort but may label a patient erroneously when in fact there is no definite physiologic reason for the patient’s complaint. It is suitable to note that the patient has hand pain or wrist pain and occasionally to tell the patient that you do not know what is wrong when it is indeed truthful. We can share with the patient that we do not understand or know everything and are not able to cure every ailment.

The second stage is a more focused examination of one or more specific systems limited to the involved hand. The system to be examined is derived based on the primary survey. At the completion of the secondary survey, we should have a preliminary diagnosis or a differential diagnosis. If a diagnosis is not apparent, one should not make up a nebulous diagnosis such as tendinitis or arthritis. These made-up diagnoses may satisfy the patient’s need to have a reason for the discomfort but may label a patient erroneously when in fact there is no definite physiologic reason for the patient’s complaint. It is suitable to note that the patient has hand pain or wrist pain and occasionally to tell the patient that you do not know what is wrong when it is indeed truthful. We can share with the patient that we do not understand or know everything and are not able to cure every ailment.

Appropriate investigations are then ordered. The history and findings of the primary and secondary surveys are correlated with the investigations. If they do not match, a focused tertiary survey should be carried out to validate the investigation. A final diagnosis is then made and necessary treatment instituted.

Appropriate investigations are then ordered. The history and findings of the primary and secondary surveys are correlated with the investigations. If they do not match, a focused tertiary survey should be carried out to validate the investigation. A final diagnosis is then made and necessary treatment instituted.

Primary Survey

The aim of the primary survey is to perform a rapid assessment of both hands to determine whether all is well.

The aim of the primary survey is to perform a rapid assessment of both hands to determine whether all is well.

Look

Move

Assess passive range of motion

Assess passive range of motion

For an expanded version of this chapter, please see www.expertconsult.com.

Secondary Survey

Assessment of Tendon and Muscle Function

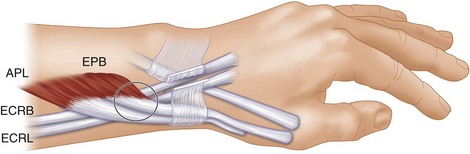

Tendinopathy: This includes a wide group of painful conditions affecting the tendons of the wrist and hand. They can be broadly classified into tenosynovitis (inflammation of the synovial lining of the tendon sheath), tendovaginitis (inflammation of the retinacular lining of the tendon sheath), tendinitis (inflammation of the tendon), tendinosis (degeneration of the tendon), and tendon subluxation.

Tendinopathy: This includes a wide group of painful conditions affecting the tendons of the wrist and hand. They can be broadly classified into tenosynovitis (inflammation of the synovial lining of the tendon sheath), tendovaginitis (inflammation of the retinacular lining of the tendon sheath), tendinitis (inflammation of the tendon), tendinosis (degeneration of the tendon), and tendon subluxation.

| Grade I | Pretriggering | History of triggering, but not demonstrable on examination |

| Grade II | Active | Demonstrable triggering, but patient can actively overcome the trigger |

| Grade III | Passive | Demonstrable trigger, but patient cannot actively overcome trigger |

| IIIA | Extension | Locked in flexion and needs passive extension to overcome trigger |

| IIIB | Flexion | Locked in extension and needs passive flexion to overcome trigger |

| Grade IV | Contracture | Demonstrable trigger with flexion contracture of proximal interphalangeal joint |

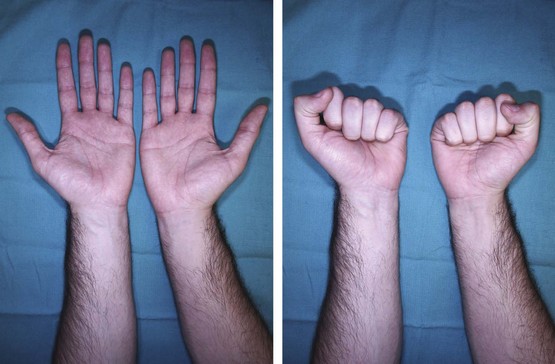

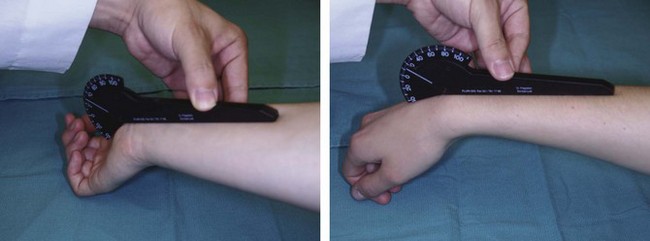

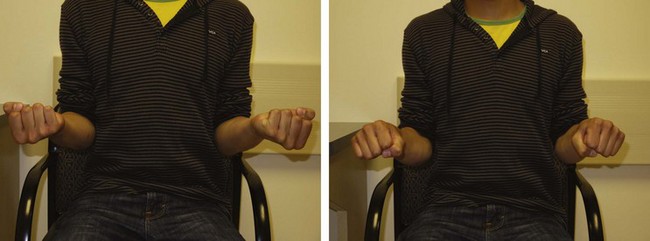

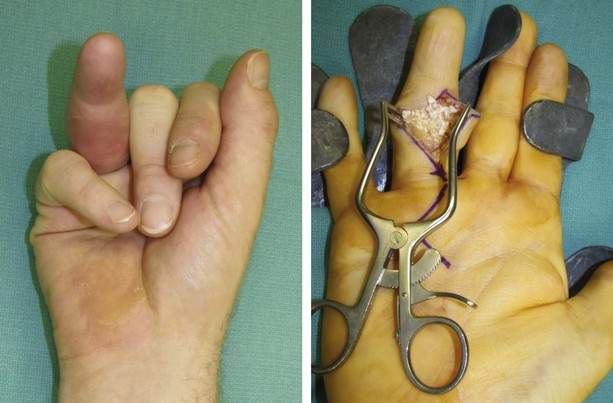

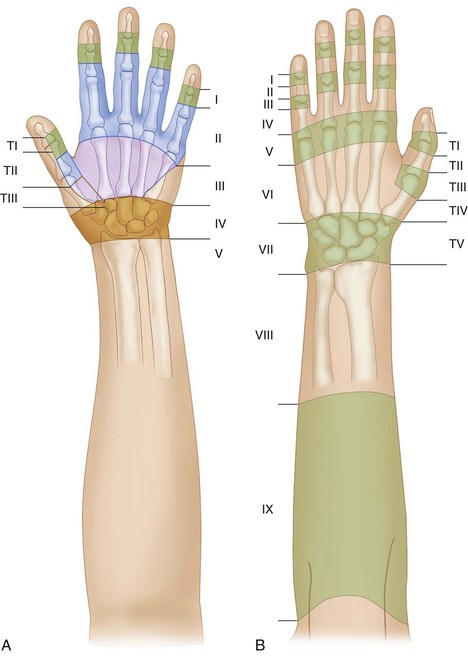

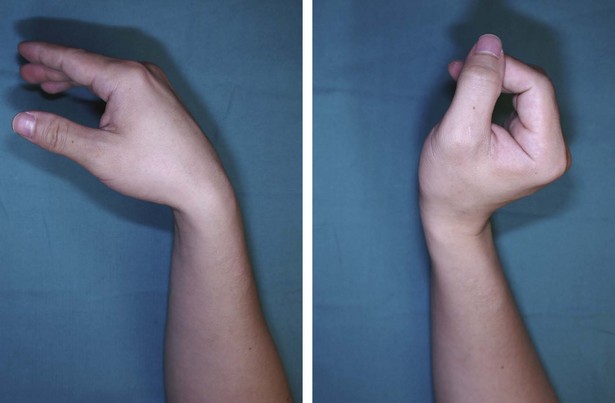

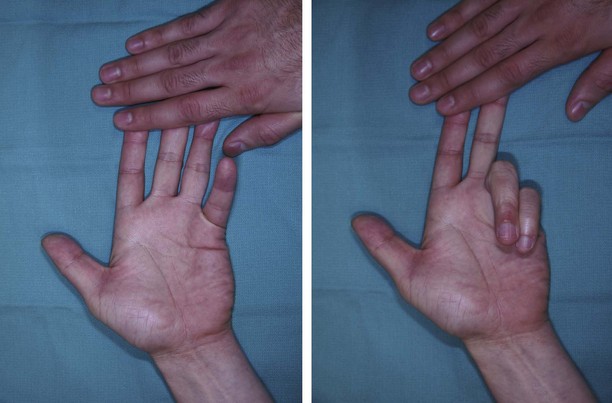

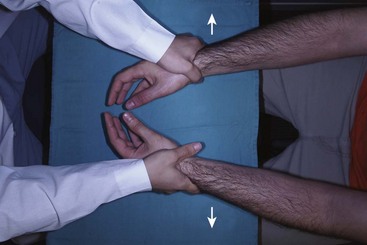

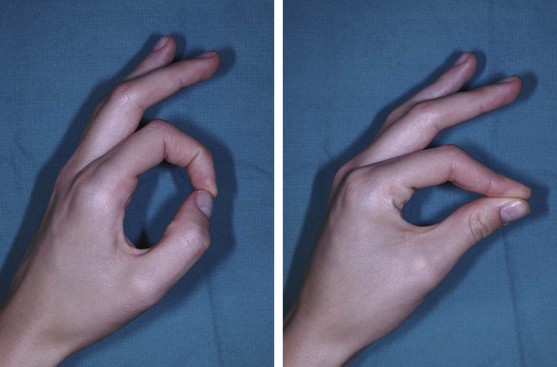

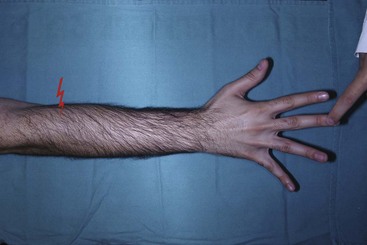

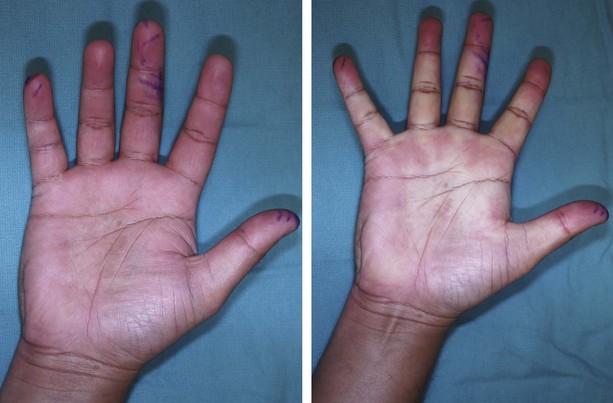

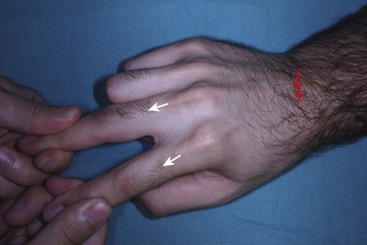

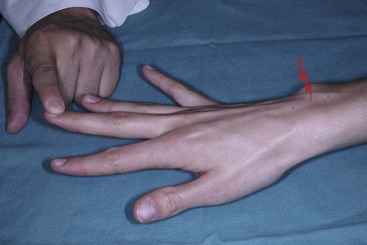

Tendon injury: A tendon injury can result from an open wound or rupture after sustaining sudden force or from chronic attrition. The zones of acute flexor and extensor tendon injuries have been depicted in Figure 1-23. The normal finger cascade is lost with tendon injury. Figure 1-24 shows the attitude of the hand with a zone 1 flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) injury, and Figure 1-25 shows the attitude of the hand in a patient with attritional rupture of the extensor tendons to the ring and small fingers. The presence of tendon injury is confirmed by asking the patient to actively flex or extend the digits. A partial tendon laceration should be suspected in patients in whom active motion is associated with pain or triggering. In patients who cannot cooperate (e.g., children, comatose or intoxicated patients), one can look for passive movement of the fingers resulting from the wrist tenodesis effect (Fig. 1-26) or elicited by squeezing the forearm muscles (Fig.1-27). The same maneuvers can be used when trying to differentiate between tendon injury and an inability to move as a result of nerve palsy.

Tendon injury: A tendon injury can result from an open wound or rupture after sustaining sudden force or from chronic attrition. The zones of acute flexor and extensor tendon injuries have been depicted in Figure 1-23. The normal finger cascade is lost with tendon injury. Figure 1-24 shows the attitude of the hand with a zone 1 flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) injury, and Figure 1-25 shows the attitude of the hand in a patient with attritional rupture of the extensor tendons to the ring and small fingers. The presence of tendon injury is confirmed by asking the patient to actively flex or extend the digits. A partial tendon laceration should be suspected in patients in whom active motion is associated with pain or triggering. In patients who cannot cooperate (e.g., children, comatose or intoxicated patients), one can look for passive movement of the fingers resulting from the wrist tenodesis effect (Fig. 1-26) or elicited by squeezing the forearm muscles (Fig.1-27). The same maneuvers can be used when trying to differentiate between tendon injury and an inability to move as a result of nerve palsy.

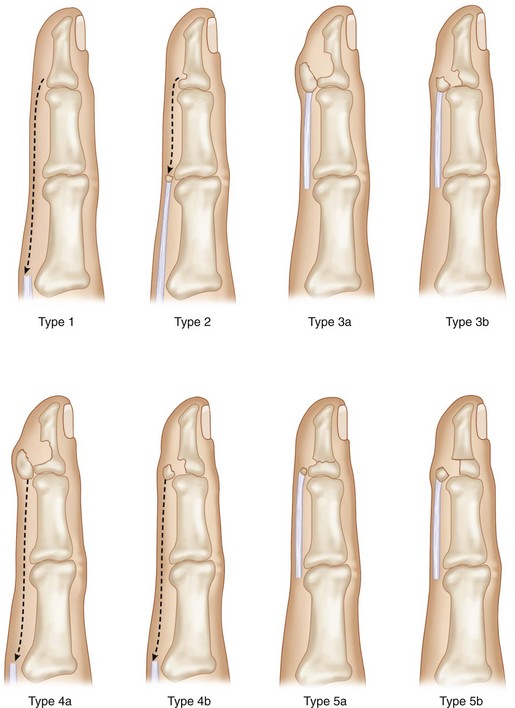

Table 1-5 Classification of Flexor Digitorum Profundus (FDP) Avulsion Injuries

| Type 1 | FDP retracted into palm |

| Type 2 | FDP retracted to level of proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint and is caught at FDS chiasma (maybe associated with small chip fracture) |

| Type 3 | FDP avulsed along with fragment of bone and is caught at A4 pulley |

| 3A | Fragment of bone is extra-articular |

| 3B | Fragment of bone is intra-articular |

| Type 4 | FDP retracted into palm with associated fragment of bone |

| 4A | Fragment of bone is extra-articular |

| 4B | Fragment of bone is intra-articular |

| Type 5 | FDP avulsed with fragment of bone and is caught at A4 pulley, and there is an additional fracture of the shaft of distal phalanx |

| 5A | Fragment of bone is extra-articular |

| 5B | Fragment of bone is intra-articular |

Table 1-6 Burton Classification of Chronic Boutonnière Deformity

| Stage I | Supple, passively correctable deformity |

| Stage II | Fixed contracture, contracted lateral bands |

| Stage III | Open injury with loss of skin, subcutaneous cover, and tendon substance |

| Stage IV | Proximal interphalangeal joint arthritis |

An assessment of the results of tendon repair is done by calculating total active motion (TAM). TAM = total active flexion (MCP + PIP + DIP joints) − total extension deficit (MCP + PIP + DIP joints). The TAM in a repaired finger can be compared with the values obtained in the uninjured contralateral finger (American Society for Surgery of the Hand [ASSH] grade) or presented as a percentage (Strickland and modified Strickland grades) (Table 1-7).

An assessment of the results of tendon repair is done by calculating total active motion (TAM). TAM = total active flexion (MCP + PIP + DIP joints) − total extension deficit (MCP + PIP + DIP joints). The TAM in a repaired finger can be compared with the values obtained in the uninjured contralateral finger (American Society for Surgery of the Hand [ASSH] grade) or presented as a percentage (Strickland and modified Strickland grades) (Table 1-7).

Assessment of Nerve Function

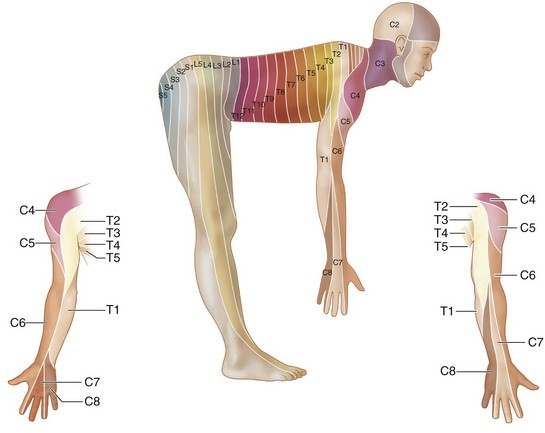

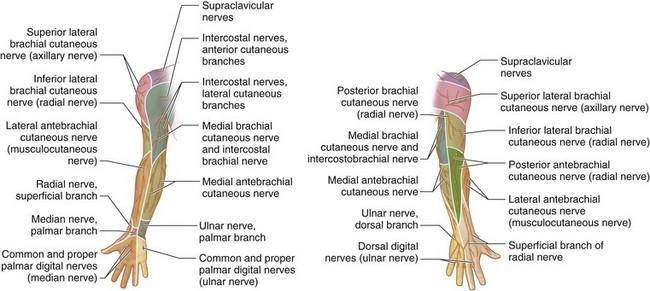

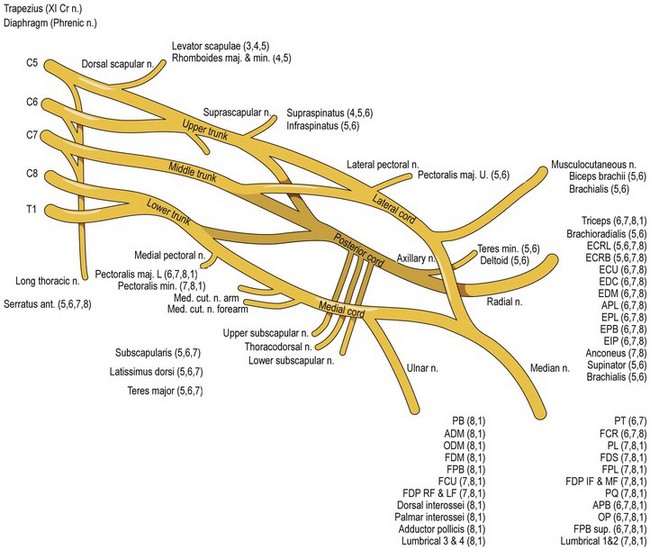

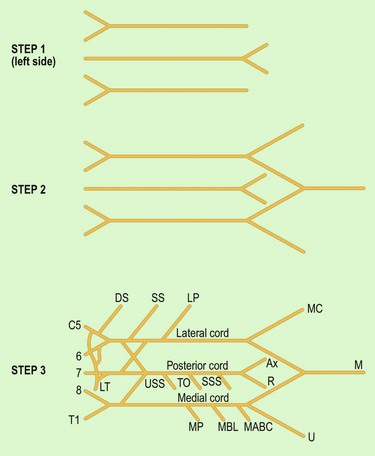

General assessment: The assessment of nerve function involves testing for sensory, motor, and autonomic function. The British Medical Council grading of motor and sensory function has been detailed in Table 1-8 and Table 1-9, respectively. The branches of the brachial plexus with root values have been depicted in Figure 1-42. Figure 1-43 shows an easy way to draw the brachial plexus. (Adapted with permission from Edwards Jr GS. ASSH Correspondence Newsletter. 1991:103.) Two additional signs are useful in following the progress of nerve regeneration. They are the Tinel sign and the tender muscle sign.

General assessment: The assessment of nerve function involves testing for sensory, motor, and autonomic function. The British Medical Council grading of motor and sensory function has been detailed in Table 1-8 and Table 1-9, respectively. The branches of the brachial plexus with root values have been depicted in Figure 1-42. Figure 1-43 shows an easy way to draw the brachial plexus. (Adapted with permission from Edwards Jr GS. ASSH Correspondence Newsletter. 1991:103.) Two additional signs are useful in following the progress of nerve regeneration. They are the Tinel sign and the tender muscle sign.

Table 1-8 Medical Research Council Grading of Muscle Function

| Grade M0 | No contraction |

| Grade M1 | Palpable contraction, no movement |

| Grade M2 | Movement with gravity eliminated |

| Grade M3 | Movement against gravity |

| Grade M4 | Movement against resistance |

| Grade M5 | Normal |

Table 1-9 Medical Research Council Grading of Sensory Function

| Grade S0 | No sensation |

| Grade SI | Deep pain |

| Grade S2 | Superficial pain and some touch |

| Grade S3 | Grade S2 without over-response |

| Grade S3+ | Grade S2 with some two-point discrimination |

| Grade S4 | Normal |

Assessment of individual nerves: The different provocative tests and signs available for diagnosis of median, ulnar, and radial nerve palsy are described next. It is useful to perform the nerve percussion test at points where nerves are not anatomically located as a negative control, especially in patients who are hyper-responsive to stimuli or have positive nerve percussion test results at multiple entrapment sites.

Assessment of individual nerves: The different provocative tests and signs available for diagnosis of median, ulnar, and radial nerve palsy are described next. It is useful to perform the nerve percussion test at points where nerves are not anatomically located as a negative control, especially in patients who are hyper-responsive to stimuli or have positive nerve percussion test results at multiple entrapment sites.

Assessment of Vascular Function

General assessment: The entire upper extremity and neck should be evaluated, and it is important to compare both sides. The fingertip is examined for color, capillary refill (normal is <2 seconds), turgor, and nail changes (loss of normal sheen and fungal infections). The extremity should be evaluated for the presence of ulcers and gangrene (dry or wet). Palpation and auscultation of visible masses overlying the course of the major vessels can detect pulsations, thrill, and bruits.

General assessment: The entire upper extremity and neck should be evaluated, and it is important to compare both sides. The fingertip is examined for color, capillary refill (normal is <2 seconds), turgor, and nail changes (loss of normal sheen and fungal infections). The extremity should be evaluated for the presence of ulcers and gangrene (dry or wet). Palpation and auscultation of visible masses overlying the course of the major vessels can detect pulsations, thrill, and bruits.

Assessment of Bone and Joint Function

General assessment: Displaced fractures and unreduced dislocations are usually quite obvious because of the associated deformity. However, the assessment of undisplaced or minimally displaced fractures and of partial or complete ligament injuries without dislocation or after reduction of a dislocation can be difficult, especially because of the associated pain and swelling. Gentle palpation can pinpoint specific sites of tenderness that can be correlated with the radiographs. A local anesthetic block may occasionally be required for accurate, painless assessment of joint stability and stress radiographic views. A simple classification of IP and MCP joint collateral ligament injuries is provided in Table 1-11.

General assessment: Displaced fractures and unreduced dislocations are usually quite obvious because of the associated deformity. However, the assessment of undisplaced or minimally displaced fractures and of partial or complete ligament injuries without dislocation or after reduction of a dislocation can be difficult, especially because of the associated pain and swelling. Gentle palpation can pinpoint specific sites of tenderness that can be correlated with the radiographs. A local anesthetic block may occasionally be required for accurate, painless assessment of joint stability and stress radiographic views. A simple classification of IP and MCP joint collateral ligament injuries is provided in Table 1-11.

Table 1-11 Classification of Collateral Ligament Injuries

| Grade I | Pain, no laxity |

| Grade II | Laxity, but a firm end point, stable arc of motion |

| Grade III | Grossly unstable, no firm end point |

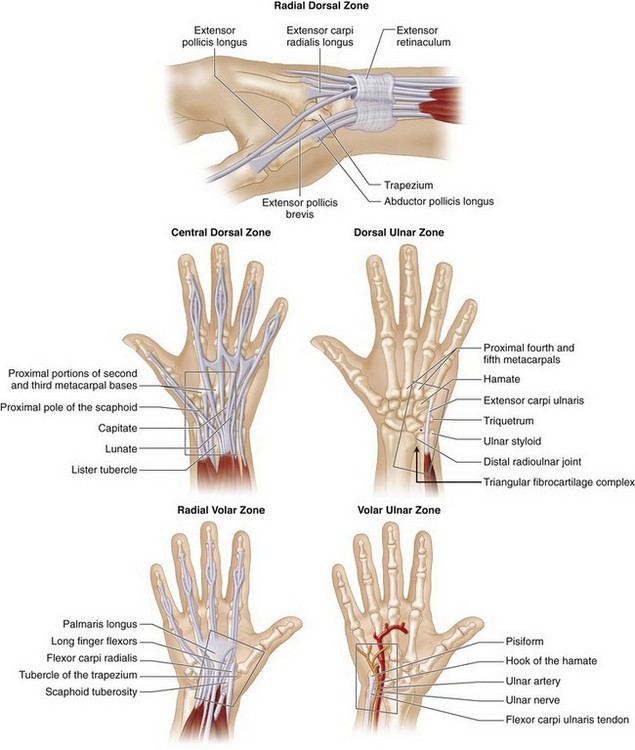

Brown and Lichtman have suggested dividing the wrist into five zones: three dorsal and two volar. Figure 1-78 shows these five zones and the differential diagnoses that should be considered in each zone. This systematic approach will help to localize the patient’s symptoms and reach an appropriate diagnosis.