CHAPTER 1

Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy

Definition

Cervical spondylotic myelopathy (CSM) is a frequently encountered entity in middle-aged and elderly patients. The condition affects both men and women. Progressive degeneration of the cervical spine involves the discs, facet joints, joints of Luschka, ligamenta flava, and laminae, leading to gradual encroachment on the spinal canal and spinal cord compromise. CSM has a fairly typical clinical presentation and, frequently, a progressive and disabling course.

As a consequence of aging, the spinal column goes through a cascade of degenerative changes that tend to affect selective regions of the spine. The cervical spine is affected in most adults, most frequently at the C4-C7 region [1,2]. Degeneration of the intervertebral discs triggers a cascade of biochemical and biomechanical changes, leading to decreased disc height, among other changes. As a result, abnormal load distribution in the motion segments causes cervical spondylosis (i.e., facet arthropathy) and neural foraminal narrowing. Disc degeneration also leads to the development of herniations (soft discs), disc calcification, posteriorly directed bone ridges (hard discs), hypertrophy of the facets and the uncinate joints, and ligamenta flava thickening. On occasion, more frequently in Asians but not infrequently in white individuals, the posterior longitudinal ligament and the ligamenta flava ossify [3]. These degenerative changes narrow the dimensions and change the shape of the cervical spinal canal. In normal adults, the anteroposterior diameter of the subaxial cervical spinal canal measures 17 to 18 mm, whereas the spinal cord diameter in the same dimension is about 10 mm. Severe CSM gradually decreases the space available for the cord and brings about cord compression in the anterior-posterior axis. Cord compression usually occurs at the discal levels [4–6].

The encroaching structures may also compress the anterior spinal artery, resulting in spinal cord ischemia that usually involves several cord segments beyond the actual compression site. Spinal cord changes in the form of demyelination, gliosis, myelomalacia, and eventually severe atrophy may develop [4,7–9]. Dynamic instability, which can be diagnosed in flexion or extension lateral x-ray views, further complicates matters. Disc degeneration leads to laxity of the supporting ligaments, bringing about anterolisthesis or retrolisthesis in flexion and extension, respectively. This may further compromise the spinal cord and intensify the presenting symptoms [2,4].

Symptoms

CSM develops gradually during a lengthy period of months to years. Not infrequently, the patient is unaware of any functional compromise, and the first person to notice that something is amiss may be a close family member. Whereas pain appears rather early in cervical radiculopathy and alerts the patient to the presence of a problem, this is usually not the case in CSM. A long history of neck discomfort and intermittent pain may frequently be obtained, but these are not prominent at the time of CSM presentation.

Most patients have a combination of upper motor neuron symptoms in the lower extremities and lower motor neuron symptoms in the upper extremities [4]. Patients frequently present with gait dysfunction resulting from a combination of factors, including ataxia due to impaired joint proprioception, hypertonicity, weakness, and muscle control deficiencies.

Studies have demonstrated that severely myelopathic patients display abnormalities of deep sensation, including vibration and joint position sense, which is attributed to compression of the posterior columns [10,11]. Paresthesias and numbness may be frequently mentioned. Compression of the pyramidal and extrapyramidal tracts can lead to spasticity, weakness, and abnormal muscle contractions. These sensory and motor deficits result in an unstable gait. Patients may complain of stiffness in the lower extremities or plain weakness manifesting as foot dragging and tripping [5]. Symptoms related to the upper extremities are mostly the result of fine motor coordination deficits. At times, the symptoms in the upper extremities are much more severe than those related to the lower extremities, attesting to central cord compromise [4]. Most patients do not have urinary symptoms. However, urinary symptoms (i.e., incontinence) may occasionally develop in patients with long-standing myelopathy [12]. As CSM develops in middle-aged and elderly patients, the urinary symptoms may be attributed to aging, comorbidities, and cord compression. Bowel incontinence is rare.

Physical Examination

Because of sensory ataxia, the patient may be observed walking with a wide-based gait. Some resort to a cane to increase the base of support and to enhance safety during ambulation. Patients with severe gait dysfunction frequently require a walker and cannot ambulate without one. Many patients lose the ability to tandem walk. The Romberg test result may become positive. Examination of the lower extremities may reveal muscle atrophy, increased muscle tone, abnormal reflexes—clonus or upgoing toes (Babinski sign), and abnormalities of position and vibration sense. Muscle fasciculations may be observed. The foot tapping test (number of sole tappings while the heel maintains contact with the floor in 10 seconds) is an easy and useful quantitative tool for lower extremity function in these patients [13].

In the upper extremities, weakness and atrophy of the small muscles of the hands may be noted. The patient may have difficulties in fine motor coordination (e.g., unbuttoning the shirt or picking a coin off the table). The patient frequently displays difficulty in performing repetitive opening and closing of the fist. In normal individuals, 20 to 30 repetitions can be performed in 10 seconds.

Weakness can occasionally be documented in more proximal muscles and may appear symmetrically. Fasciculations may appear in the wasted muscles. Hypesthesia, paresthesia, or anesthesia may be documented. On occasion, the sensory findings in the hands are in a glove distribution. As in the lower extremities, the vibration and joint position senses may be disturbed. Hyporeflexia or hyperreflexia may be found. The Hoffmann response may become positive and can be facilitated in early myelopathy by cervical extension [14]. In some patients, severe atrophy of all the hand intrinsic muscles is observed [1,5,15,16].

The neck range of motion may be limited in all directions. Many patients cannot extend the neck beyond neutral and may feel electric-like sensation radiating down the torso on neck flexion, known as the Lhermitte sign. Often, when a patient stands against the wall, the back of the head stays an inch to several inches away, and the patient is unable to push the head backward to bring it to touch the wall.

Functional Limitations

Patients with CSM have difficulties with activities of daily living. Patients may have difficulties inserting keys, picking up coins, buttoning a shirt, or manipulating small objects. Handwriting may deteriorate. Patients may drop things from the hands and occasionally can complain of numbness affecting the fingers or the palms, mimicking peripheral neuropathy [2,5,15,17,18]. They may have problems dressing and undressing. When weakness is a predominant feature, they will be unable to carry heavy objects. Unassisted ambulation may become difficult. The gait is slowed and becomes inefficient. In late stages of CSM, patients may become almost totally disabled and require assistance with most activities of daily living.

Diagnostic Studies

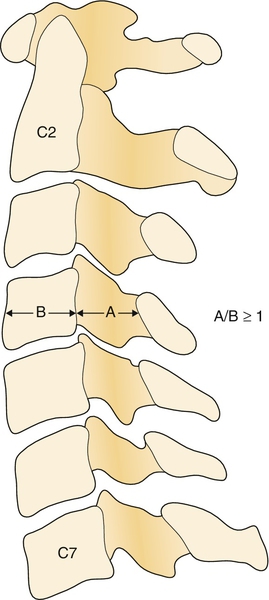

Plain radiographs usually reveal multilevel degenerative disc disease with cervical spondylosis. Dynamic studies (flexion and extension views) may reveal segmental instability with anterolisthesis on flexion and retrolisthesis on extension. In patients with ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament, the ossified ligament may be detected on lateral plain films. The Torg-Pavlov ratio may help diagnose congenital spinal stenosis. This ratio can be obtained on plain films by dividing the anteroposterior diameter of the vertebral body by the anteroposterior diameter of the spinal canal at that level. The canal diameter can be measured from the posterior wall of the vertebra to the spinolaminar line [19]. A ratio of 0.8 and below is indicative of spinal stenosis (Fig. 1.1) [20].

Magnetic resonance imaging, the study of choice, provides critical information about the extent of stenosis and the condition of the compressed spinal cord. Sagittal and axial cuts clearly show the offending structures (discs, thickened ligamenta flava), and the cord shape and signal provide critical information about the extent of cord compression and the prognosis (Fig. 1.2). Increased cord signal on T2-weighted images is abnormal and points to the presence of edema, demyelination, myelomalacia, or gliosis. Decreased cord signal on T1-weighted images may also be observed. However, these cord signal changes are of limited value in predicting functional outcome. A newer magnetic resonance imaging technique, diffusion tensor imaging of the cervical cord, holds considerable promise in predicting the severity of cord injury and may help guide the clinician in deciding whether to operate because it may show cord abnormalities before the development of T2 hyperintensity on conventional sequences [21,22]. Severe cord atrophy denotes a poor prognosis even when decompressive surgery is performed.

Computed tomographic myelography provides fine and detailed information on the amount and location of neural compression and is frequently obtained before surgery. Electrodiagnostic studies play an important role, especially in diabetic patients with peripheral neuropathy, which may confound the clinical diagnosis.

Treatment

Initial

The treatment of CSM depends on the stage in which it is discovered. No conservative treatment can be expected to decompress the spinal cord. In the initial stages, education of the patient is of paramount importance. The patient is instructed to avoid cervical spinal hyperextension. As the cervical spinal canal diameter decreases and the spinal cord diameter increases during cervical hyperextension, this position may lead to further cord compression [24]. The patient is advised to drink with a straw and to avoid prolonged overhead activities.

Rehabilitation

Because the course of CSM may be unpredictable and a significant percentage of patients deteriorate in a slow stepwise course, close monitoring of the patient’s neurologic condition and spine is indicated. Patients with mild CSM may be managed conservatively. A biannual detailed neurologic examination and an annual magnetic resonance imaging evaluation are indicated. Special attention should be devoted to the cord cross-sectional area and the cord signal; these are important prognostic factors and may help determine whether surgery is indicated. In the interim, patients should be instructed in static neck exercises. Weak muscles in the upper or lower extremities should be strengthened with progressive resistance exercise techniques. Judicial use of anti-inflammatory medications is called for, especially in elderly individuals. Soft cervical collars are frequently used (recommended by physicians or obtained by patients without the physician’s recommendations) without a sound scientific basis. Assistive devices, such as a cane or walker, should be provided when ambulation safety is compromised.

Procedures

No existing procedures affect the course or symptoms of cervical myelopathy.

Surgery

Patients with moderate to severe progressive CSM (unsteady gait, limited function in the upper extremities) who have significant cord compression or cord signal changes should be referred for decompressive surgery. Two main approaches exist—anterior and posterior.

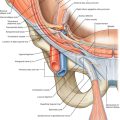

Anterior Approach

The anterior approach is usually reserved for patients with myelopathy affecting up to three spinal levels. This approach allows adequate decompression of “anterior” disease. Anterior disease refers to pathologic changes that are anterior to the spinal cord (e.g., soft disc, hard disc, vertebral body spurs, and ossified posterior longitudinal ligament). Through this approach, the offending structures can be removed without disturbing the spinal cord. The anterior approach allows adequate decompression in patients with cervical kyphotic deformity. After anterior decompression (anterior cervical decompression and fusion, corpectomies), bone grafting and instrumentation ensure stabilization and fusion. This approach is not indicated in patients whose predominant pathologic process is posterior to the cord (i.e., hypertrophied ligamentum flavum) or in patients with disease affecting more than three or four segments because this may lead to an increased rate of complications, including pseudarthrosis [6,16].

Posterior Approach

The posterior approach consists of two basic procedures, laminectomy and laminoplasty.

Cervical laminectomy can be easily performed by most spinal surgeons and is less technically demanding than anterior corpectomies are. This approach allows easy access to posterior disease, such as hypertrophied laminae and ligamenta flava. The main disadvantage of the laminectomy procedure is that it requires stripping of the paraspinal muscles and thus tends to destabilize the cervical spine. This may result in loss of the cervical lordosis or frank kyphotic deformity and instability (stepladder deformity), especially when it is performed over several spinal levels or when the facet joints have to be sacrificed.

Laminoplasty, another procedure performed through the posterior approach, has been developed in Japan and addresses some of the shortcomings of laminectomy. Unlike laminectomy, cervical laminoplasty preserves the cervical facets and the laminae. In this procedure, the laminae are hinged away (lifted by an osteotomy) from the site of main pathologic change, resulting in an increase of sagittal canal diameter [25]. Unilateral or bilateral hinges can be performed; the bilateral hinge approach allows symmetric expansion of the spinal canal. It is hoped that after posterior decompression, the spinal cord will “migrate” away from the anterior pathologic process, and thus cord decompression will be achieved [16,26]. This has been confirmed in magnetic resonance imaging studies after laminoplasty.

Regardless of the surgical approach, poor outcome and higher complication rate can be expected in elderly patients with long-standing myelopathy and spinal cord atrophy [27].

Potential Disease Complications

Left untreated, a patient with progressive myelopathy may develop severe disability. Patients may become totally dependent and nonambulatory. In some cases, neurogenic bladder may develop and further compromise the quality of life.

Potential Treatment Complications

Pseudarthrosis, restenosis, spinal instability, postoperative radiculopathy, kyphotic deformity, and axial pain are among the surgical complications [14].