CHAPTER 1. AIRWAY CARE WITH SIMPLE DEVICES

Airway management2

The first procedure used for airway control was probably tracheostomy. Pedro Virgili (1699–1776) from Cadiz used it for the relief of quinsy, but its popularity was assured by its success in the management of diphtheria. The first to use it in the UK for diphtheria was George Martine (1702–1741). The eminent surgeon Sir William MacEwen (1848–1924) first performed intubation of the upper laryngeal orifice and trachea in 1878 as an alternative to tracheostomy, again for the management of life-threatening airway obstruction due to diphtheria.

INTRODUCTION

The assessment of airway patency and its safeguard are essential skills for acute life-support. Recognition of an obstructed airway is initially manifested by a combination of ventilatory efforts and airway sounds reflecting airflow turbulence, which become relatively quickly complicated by the signs of inadequate respiratory function such as cyanosis, tachycardia, and loss of consciousness.

VENTILATORY EFFORT

• Increased accessory muscle activity.

• Mouth opening with each inspiratory effort.

• Suprasternal and chest wall indrawing rather than chest expansion with every inspiratory effort.

AIRWAY SOUNDS

• Stridor – a harsh noise produced on aggressively trying to inspire air to overcome an obstruction at or above the level of the larynx.

• Wheeze – a sound heard at the mouth or on chest auscultation during expiration.

— The pitch of the wheeze may be described as polyphonic, commonly observed in asthma and chronic obstructive airways disease. This sound suggests many airways of differing calibre are simultaneously in varying states of compromise due to spasm and/or narrowing secondary to mucosal inflammation. The wheeze of asthma is easily heard at the mouth and confirmed by chest auscultation.

— Wheeze with a single sound (monophonic) particularly located in just one area indicates obstruction of a single bronchus, e.g. by tumour. The fixed wheeze (also called rhonchus) of bronchial obstruction is not e asily heard at the mouth.

• Crowing – a loud sound heard with every inspiration not dissimilar to stridor and suggests turbulent flow due to flow through a narrow orifice commonly heard during laryngeal spasm.

• Gurgling – the sound of air bubbling through liquid or semi-solid debris in the upper airways is mostly heard during inspiration.

• Snoring – a long inspiratory sound associated with partial occlusion of the pharynx by the tongue or soft palate.

Tip Box

Tip Box

An obstructed airway is a clinical emergency. If you are not confident in managing the airway, call for immediate anaesthetic assistance.

AIRWAY MANAGEMENT

AIRWAY CLEARANCE

Look inside the oral cavity and remove any vomitus, debris or foreign bodies with the following devices:

• Yankauer sucker (Fig. 1.1 A) – a rigid suction device that is attached to a vacuum collection system for facilitating removal of liquid or semi-solid debris from the oropharynx.

• Magill’s forceps (Fig. 1.1 B) – in the acute setting these are used to remove foreign bodies from the oral cavity. Magill’s forceps are also used to guide nasogastric tubes into the oesophagus under direct vision and to place pharyngeal packs.

BASIC AIRWAY TECHNIQUES

• Head tilt, chin lift (Fig. 1.2): avoid if suspected cervical spine trauma – place one hand on the patient’s forehead and the fingertips of your other hand under the patient’s chin. Whilst gently tilting the head back lift the patient’s chin to open the airway.

|

| Fig. 1.2 |

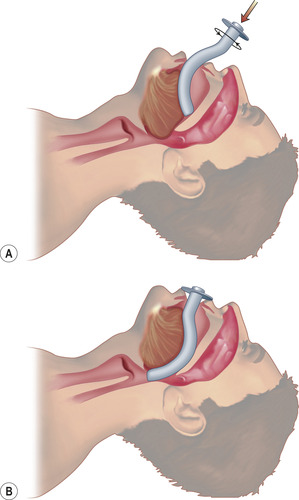

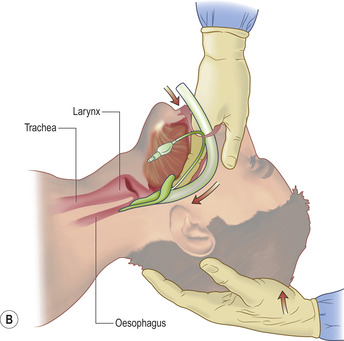

• Jaw thrust (Fig. 1.3) – this is the technique of choice in the presence of suspected cervical spine injury. Place the index fingers behind the angle of the mandible and apply steady upwards pressure to bring the mandible forwards. Slightly open the mouth by downwards displacement of the chin with your thumbs.

|

| Fig. 1.3 |

Tip Box

Tip Box

Suspected C-spine injury – The jaw thrust is the technique of choice in such patients for basic airway management, with manual in-line stabilization of the head and neck performed by a second operator. However, the primary and over-riding objective in all cases is the maintenance of a patent airway as an obstructed airway is the most immediate threat to life.

AIRWAY ADJUNCTS

Oropharyngeal (Guedel) airways

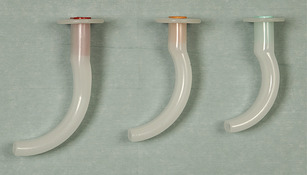

Curved plastic tubes with a flange that fit between the tongue and hard palate thereby maintaining a patent oropharynx (Fig. 1.4). If glossopharyngeal or laryngeal reflexes are present, the insertion of a Guedel airway may stimulate vomiting or laryngospasm, respectively. Hence, these should only be inserted in the comatose patient.

|

| Fig. 1.4 |

The size of the oropharyngeal airway is that size which matches:

See Fig. 1.6 for how to introduce the Guedel airway. Using this technique minimizes the risk of pushing the tongue backwards.

• A suction catheter can be passed down the oropharyngeal airway to clear liquid or semi-solid debris.

• Once the Guedel airway is placed make sure the flange is not sitting proud outside the mouth. The airway can be kept in place with your thumbs and this manoeuvre may need to be combined with jaw thrust to ensure complete patency.

• The chest should be moving freely with no evidence of upper airway obstruction, such as suprasternal recession with ventilatory effort. If in doubt recheck the placement of the Guedel airway.

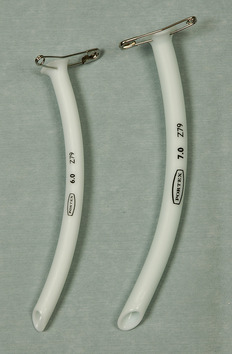

Nasopharyngeal airways

These provide a patent nasopharyngeal airway in patients in whom an oropharyngeal airway is unsuitable, either because the patient is not deeply unconscious or because of lack of oral access (e.g. trismus or maxillofacial trauma) (Fig. 1.7).

|

| Fig. 1.7 |

• Having lubricated the airway with a water-based jelly, it is inserted into the nostril bevel-first and passed in a posterior direction with a slight twisting motion.

• The airway should be inserted such that the flange should lie at the level of the nostril. A safety pin is placed through the flange prior to insertion in order to prevent the airway slipping beyond the nares.

Note that patients on anticoagulants or platelet-function-modifying drugs may bleed during this procedure. This is a necessary risk if the airway is compromised. A suction catheter can be passed down the nasopharyngeal airway to clear liquid or semi-solid debris, although care should be taken as this can cause the patient to gag and subsequently vomit.

Tip Box

Tip Box

Nasopharyngeal airways are contraindicated in suspected base of skull fracture, the signs of which include:

• CSF rhinorrhoea or otorrhoea

• ‘Racoon eyes’ – bruising of the orbits resulting from blood collecting from the fracture site

• ‘Battle’s sign’ – bruising behind the ears from blood collecting from the fracture site

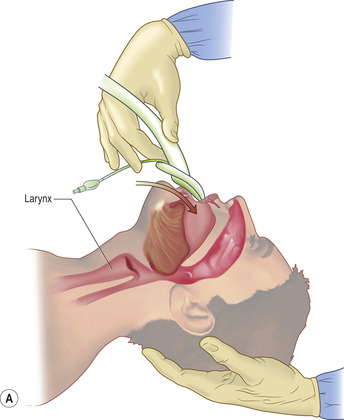

Laryngeal mask airway (LMA)

Whilst an LMA (Fig. 1.8) is not as definitive as an endotracheal tube, it is a reliable airway adjunct that can be used by medical professionals with a range of experience levels.

• Prior to using the LMA check the integrity of the cuff by inflating it with the required volume of air stipulated on the device.

• Fully deflate the cuff and liberally apply lubricating jelly to the outer face of the cuff.

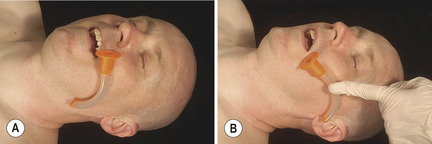

• Hold the LMA like a pen and insert into the oral cavity tip-first and with the aperture pointing downwards (Fig. 1.9 A).

• Advance the LMA with the upper surface against the palate. Upon reaching the pharyngeal wall press the LMA backwards and downwards around the corner of the pharynx. The operator will feel resistance once the LMA is located in the back of the hypopharynx (Fig. 1.9 B).

• Inflate the cuff with the volume of air stated on the device from a syringe.

• Auscultate the chest bilaterally for air entry and inspect the chest wall for bilateral movement. If air entry is not noted bilaterally then the LMA should be deflated and immediately removed. Ventilation should subsequently recommence with a bag–valve–mask until it is suitable to either retry with an LMA or an anaesthetist attends to place an endotracheal tube.

Tip Box

Tip Box

Take care to avoid lacerating the patient’s upper lip against their teeth whilst inserting the LMA.

OXYGEN DELIVERY

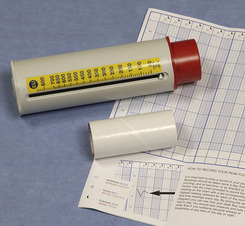

Venturi mask valves

These devices allow controlled oxygen therapy for self-ventilating patients with chronic obstructive airways disease (Fig. 1.10 and Table 1.1). They attach to a face mask and oxygen tubing and deliver oxygen at a predetermined rate indicated on the valve. Depending upon the aperture size on the valve device, a fixed fractional inspired oxygen concentration (FiO2) is subsequently delivered to the mask. It should be remembered, however, that in the acute setting of respiratory distress, first priority must be given to the management of hypoxia using high FiO2 delivery systems such as the non-rebreathe mask.

| Venturi valve colour | Flow rate (L/min) | FiO2 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Blue | 2 | 24 |

| White | 4 | 28 |

| Yellow | 8 | 35 |

| Red | 10 | 40 |

| Green | 15 | 60 |

Non-rebreathe oxygen mask

Oxygen is delivered via tubing at 10–15 L/min to the reservoir bag, which is initially filled by manually occluding the one-way valve. Having attached the mask to the face (see Fig. 1.11), oxygen is inspired by the patient from the reservoir bag thereby increasing the FiO2. Expired air escapes to the atmosphere via the mask apertures, and in doing so closes the one-way valve between the mask and the reservoir bag. This allows the reservoir bag to automatically refill with oxygen between breaths, and separates inhaled and exhaled gases (hence a ‘non-rebreathe’ mask).

|

| Fig. 1.11 |

Bag–valve–mask device (Fig. 1.12)

This three-part device is indicated for use in patients who are either apnoeic or who are not ventilating adequately. The three parts include:

|

| Fig. 1.12 |

• a reservoir bag that can be filled with oxygen

• a ventilating bag that, when compressed, passes oxygen towards the patient

• a one-way valve between the ventilating bag and the face mask, which permits the flow of inspiratory gas to the patient but closes to expired gas from the patient, thus allowing only the contents of the reservoir bag to serve as inhaled gas.

The bag–valve apparatus can not only be connected to a face mask, but also to a laryngeal mask or endotracheal tube to deliver ventilatory support. If the bag–valve is connected to a face mask it is easier to have two operators (Fig. 1.13). One operator ensures satisfactory and secure placement of the tight fitting–mask whilst tilting the patient’s head and lifting their chin, the other squeezes the contents of the bag with two hands (see Fig. 1.13).

100% oxygen can be delivered by the apparatus by attaching a fast-flow oxygen supply (10 L/min) to the reservoir bag. Gases breathed out are vented through the one-way valve to the atmosphere.