literally be a matter of life and death and is often an essential influence on quality of life, it is charged with strong emotions and is concerned with fundamental societal values. Despite attempts to ‘roll back the role of the state’ public health and healthcare are still regarded as primarily the responsibility of governments. In Australia, more than two-thirds of total health expenditure comes from government sources (see Ch 4, Fig 4.2; Ch 6, Table 6.1). Not surprisingly, health is a major electoral issue.

SEMANTICS: THE PROBLEM OF THE WORD ‘PROBLEM’

Before exploring the place of the problem in policy analysis, it is important to consider how we will use this concept since the context in which this word is used (or not used) is revealing about the very process of problem definition. The observer of both popular and official usage cannot fail to note how the word ‘problem’ is no longer applied where once it was regarded as appropriate. During the writing of this chapter a major power blackout in Victoria was explained in a radio interview with an official of the electricity corporation as a bushfire causing ‘an issue’ with the power grid! A computer-based word search of the most recent annual review from the Secretary of the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing failed to find a single instance of the word ‘problem’.

Perhaps too blunt and negative for an era of ‘spin doctoring’ in which language is increasingly tempered by public relations considerations, the word ‘problem’ is often eschewed by policy makers, and even some policy analysts, in favour of the more neutral ‘issue’. Sometimes the two terms are used interchangeably. On occasions ‘concerns’, ‘matters’ and ‘situation’ are referred to. Increasingly the optimistic term ‘challenge’ is employed in lieu of ‘problem’, a usage that taps into the notion of problems as ‘opportunities’ demanding an attempt to make things better. When greater linguistic impact is needed, the often hyperbolic ‘crisis’, ‘disaster’ or even ‘chaos’ might be invoked.

Yet the conventional usage of problem, described in the Shorter Oxford Dictionary as a ‘difficult question proposed for a solution’ or a ‘proposition in which something is required to be done’, also adequately suits the purpose of policy analysis. As Kingdon puts it, for a condition to become a problem ‘people must be convinced that something should be done to change it’ (Kingdon 1984 p 118). It is common for a problem to be seen as something undesirable (Weimer & Vining 1992 p 206) or as a ‘mismatch between observed conditions and one’s conception of an ideal state’ (Kingdon 1984 p 116). However, for Dery, author of a major study on problem definition in policy analysis, it is not useful to approach problems as ‘undesirable situations, discrepancies between a given state and a desired state, or bridgeable discrepancies’ (Dery 1984 p 26). Rather, they ‘are better treated as opportunities for improvement’ (Dery 1984 p 27).

PROBLEM SOLVING AND POLICY ANALYSIS

The centrality of the problem to policy analysis is commonplace in the literature. Parsons regards policy analysts as being ‘in the business of problem-structuring and ordering so as to facilitate problem solving by decision makers’ (Parson 1995 p 88). For Quade, the purpose of policy analysis is ‘to help (or sometimes influence) a decision maker to make a better decision in a particular problem situation’ (Quade 1989 p 13).

Problem recognition and definition is identified as the first stage of the policy cycle by a number of writers (see e.g. Bridgman & Davis 2000 p 49; Davis et al. 1993 pp 160–1). Howlett and Ramesh (see Table 1.1) suggest various phases at which a problem-solving approach relates to the policy cycle or process commonly suggested in policy analysis texts.

|

Table 1.1 The relationship of the policy cycle to applied problem solving |

|

| Phases of applied problem solving | Stages in the policy cycle |

|---|---|

| 1. Problem recognition | 1. Agenda setting |

| 2. Proposal solution | 2. Policy formulation |

| 3. Choice of solution | 3. Decision making |

| 4. Putting solution into effect | 4. Policy implementation |

| 5. Monitoring result | 5. Policy evaluation |

|

Source: Howlett & Ramesh 1995 p 11 |

|

But a number of caveats apply to such a linear approach and also to some of the assumptions inherent in the language used. Both Wildavsky and Dery pose a ‘reality check’ which might be startling for some students of public policy: that policy analysis is concerned with creating problems which are worth solving and which have some prospect of being solved, thereby suggesting that solution identification leads to problem definition rather than vice versa (Wildavsky 1980 p 17, Dery 1984 pp 23–5). For Dery, problem definition ‘must be instrumental to problem solving’ (Dery 1984 p 26) since there is no useful purpose served by defining problems that cannot be solved or can only be solved by violating other values, thereby making the solution unacceptable (p 9). Indeed, these concerns with practicality are common to the very definition of policy:

A set of interrelated decisions taken by a political actor or group of actors concerning the selection of goals and the means of achieving them within a specified situation where these decisions should, in principle, be within the power of these actors to achieve.(Roberts quoted in Jenkins 1978 p 15, emphasis added)

Notwithstanding the ways in which problems are perceived and interpreted and the influences shaping interpretation, the fundamental concern with problem definition is that of solutions. As Dery concludes, problem definition has to be instrumental to problem solving (Dery 1984 p 26). The process of problem definition involves the ‘search, creation and initial examination of ideas for solutions until a problem of choice is reached’ (p 27).

Nevertheless, we should not let the magnitude of some problems prevent efforts to deal with them. Efforts to deal with global climate change, which rely upon common action on the part of all nations and the probability of reduced standards of living, might be portrayed as impractical, undesirable or impossible and consequently not permitted on the policy agenda. Yet the potential consequences of policy inaction are literally disastrous.

Quade enjoins modesty in approaching the task of problem solving, observing that since it is rare that a single alternative to deal with a problem is obvious, ‘the analyst does not even try to offer more than suggestions as to what the choice should be – there is too much uncertainty and too many differing views of equity and of values for that’ (Quade 1989 p 14). The analyst, therefore, can often do little more than contribute to the quality and quantity of information available to the policy decision maker.

It is common to include a ‘feedback’ loop in policy process models since decisions by policy makers often lead to further demands upon the decision makers. Wildavsky reminds us that solutions are usually both temporary and partial, since conditions producing the initial problem often change over time and new problems arise, sometimes even caused by the initial attempts to provide solutions (Wildavsky 1979 p 390). Subsequent evaluation of problem definition and chosen solutions should therefore be an integral element of applied problem solving.

PROBLEM DEFINITION

It is clear from the preceding discussion of problem solving and policy analysis that, while problem definition is central to a problem-oriented approach to policy analysis, problems are not necessarily self-evident. Parsons puts it simply, maintaining that a policy ‘has to be defined, structured, located within certain boundaries and given a name’ (Parsons 1995 p 88). This task must, of necessity, involve both individual and societal perceptions, which in turn are influenced by values. As Brewer and deLeon caution, the ‘very recognition of a problem implies a certain set of values and goals on the part of the individual’ (Brewer & deLeon 1983 p 35). The availability of information about a particular problem, and how this is transmitted, will also be significant. Where data about a problem are not collected, or their dissemination is suppressed, agenda setting is hampered or can even be made impossible. For example, at Federation, the Australian Constitution excluded the Aboriginal population from being counted in any census. Although this provision was overturned by the 1967 referendum, policy on Indigenous health has historically been hampered by serious deficiencies in the collection of statistics. Finally, the ‘discourse’ or ‘policy story’ gives the problem its shape and meaning, although in some cases there is more than one account of the problem. The whole enterprise of policy definition is therefore subjective. As Wildavsky muses, ‘our rationalisations, once made, are just as real as our other creations’ (Wildavsky 1980 p 390).

Brewer and deLeon point out that the ‘perception and recognition of a policy problem can be treated as both individual and institutional phenomena’ (Brewer & deLeon 1983 p 35). Wildavsky goes as far as conceding that it is difficult to say ‘whether what we consider a policy problem is in us or in society’ (Wildavsky 1980 p 389). The individual analyst needs to bring the problem to the attention of the organisation.

The perceptions of individual analysts might, or might not, be accepted by institutions or organisations that play instrumental roles in shaping the policy agenda. It is only when the political system embraces problems that they become part of the policy process. Indeed, it is usually only when problems are recognised by agencies of the state and seen to have wider societal ramifications that they are placed on the policy agenda. Such agencies are commonly governments, parliaments and municipal councils, bureaucracies, the judiciary and councils of state. In Australia, medical associations have been concerned about the commercial endorsement of non-prescription therapeutic products and the selling of alternative medicines by registered medical practitioners, but it took some time for the Australian government to recognise this as a problem and take steps to prohibit such practices.

For those concerned with the exercise of power in the policy process, the ways in which problems reach the policy agenda, or are prevented from so doing, is of particular concern. Governments might choose to ignore problems, since the economic or political costs of attending to them is considered too great. Moreover, in the first place there must be consciousness about the problem, and its nature, on the part of individuals or groups. As Lukes reminds us, the shaping of people’s thoughts and desires is the supreme exercise of power (Lukes 1994 p 23). Keeping problems off the policy agenda, or preventing or limiting consciousness about them, is thus an exercise of political power.

Howlett and Ramesh emphasise the significance of institutions and also of values in problem definition, observing that:

The context of societal, state and international institutions and the values these institutions embody condition how a problem is defined, facilitate the adoption of certain solutions to it, and prohibit or inhibit the choice of other solutions.

As will be seen in Section 3 of this book, values are an essential element of health policy and are often contested. At times, support for the realisation of cherished values comes at a high economic price and stands in contrast to such economic values as efficiency, since special services must be provided for particular population groups. At other times, symbolic recognition is sufficient to satisfy demands for incorporating certain values in public policy. Moreover, some values are recognised in multilateral treaties and these are sometimes invoked as part of efforts to influence the shape of policy.

CATEGORIES OF HEALTH POLICY PROBLEMS

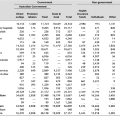

The first step in a problem-oriented approach to policy analysis is to seek to establish the type or category of problem. As Dery admonishes, ‘… in order to define a problem it is necessary to determine what kind of problem it is’ (Dery 1984 p 4, emphasis in original). In so doing, we need to be mindful that the very process of categorisation serves to define how we look at a problem. Table 1.2, while not exhaustive, suggests some types of problems to be found in health policy in Australia.

KINGDON ON PROBLEMS AND THE POLICY AGENDA

Kingdon made a major contribution to problem-oriented policy analysis in his study of agenda setting in the areas of transport and health in the United States, in which he identified a range of influences on how problems came to be on the policy agenda (Kingdon 1984). These find ready application to the Australian experience and are used in the discussion that follows and by several of the chapters in this book.

Indicators are commonly a source of problem identification and agenda setting. Various government and non-government agencies monitor developments ranging from consumer prices to climate patterns. On occasions, formal audits of performance are conducted. In the health field, data are routinely collected on such things as morbidity and mortality, expenditure, service use and workforce. Data collected and reported on by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) and the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) are regularly used to point to problems and are employed in demands on policy makers and by policy makers themselves in developing policy (see Ch 4).

Comparative data are also significant. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and the Commonwealth Fund regularly publish reports comparing such things as average bed days spent in hospitals, expenditure per capita on pharmaceutical products and levels of client satisfaction with services (see Ch 3). Such comparisons are commonly made between countries with similar levels of economic development. In the case of the Commonwealth Fund the comparisons are between English-speaking nations (the United States, United Kingdom, New Zealand, Canada and Australia) which, to some extent, can be said to share some common cultural attributes. Data comparing different states and territories within Australia are also available to policy makers.

How the data contained in such indicators are interpreted ‘transforms them from statements of conditions to statements of policy problems’ (Kingdon 1984 p 99). The data might be used to assess the magnitude of a particular problem or establish that a problem exists. Sometimes there is conflict about the method used to gather and interpret data.

Obesity and overweight is a contemporary problem surrounded by differences of interpretation. The AIHW self-reported data suggest an increase in the prevalence of obesity in the decade to 2001 from 9.5% to 16.7% of the population. Moreover, Queensland, with a prevalence rate of 18.5%, has the highest prevalence, while the ACT, with 13.5%, has the lowest. Lower socioeconomic status correlated with higher rates of overweight (AIHW 2003). Do such data justify the declaration of obesity as an epidemic and is such a disease-based construction appropriate? Moreover, is the definition of obesity cultural and therefore relative? In previous eras, the sin of gluttony described excessive consumption of food by individuals. Should the problem be formulated in such a way that it justifies the protection of the population from corporations seeking to promote the consumption of food considered to be contributing to the rise of obesity and overweight?

As is suggested in the final stage of the policy cycle (see Table 1.1) the implementation and evaluation of policy might also provide feedback in the form of indicators relevant to the problem. Such indicators might include the results of formal evaluations, the experience of those implementing a particular program, and complaints or representations received from clients or from the public. Kingdon also alerts us to the phenomenon of unintended consequences.

Certainly, the deinstitutionalisation of mental healthcare is often cited, both in Australia and other countries, as an example of a well-meaning policy reform with serious unintended negative consequences. Government and non-government evaluations of the implementation of mental health policy have found serious problems, leading to concerted national action in an attempt to ameliorate the dire conditions experienced by many Australians with mental illness (see Ch 18).

Sometimes it is a ‘focusing event’, such as a crisis or disaster, which serves to bring a problem to the attention of policy makers. Moreover, such a particular event might take on symbolic meaning for wider systemic problems. In the Australian health policy context it is clear that the ‘Dr Patel incident’, relating to medical incompetence in a Queensland public hospital, came to symbolise more general problems with administration of public healthcare in that state (see Ch 15, Box 15.2). However, it also spilled into the national policy arena, highlighting the sensitive topic of recruiting foreign medical personnel and the role of governments in monitoring such recruitment.

At times, advocates for a particular policy might capitalise on a current incident or event to further their cause. This usually involves the use of the mass media. In March 2007 Billy Thorpe, a popular Australian rock and roll singer, died suddenly at the age of 60 after a heart attack. For the director of a heart research foundation, this provided an opportunity to use the singer’s death to dramatise what he considered as a major gap in public policy: that cardiovascular disease is a national health priority but lacks its own designated expenditure within a federal government program (Jennings 2007 p 10).

New technologies are also a source of problems. In health policy, biotechnology and information technology have posed major financial and ethical policy challenges. The cost and pace of change create problems for hospitals wanting to introduce the latest, and usually less invasive, technology, as is the case of robotics in prostate cancer surgery. Men’s health is becoming a public problem and prostate cancer is an emotive issue, particularly in the context of an ageing population. Chapter 19 discusses new technology in prostate cancer surgery. In vitro fertilisation has caused policy pain for governments, not only in terms of the cost of subsidising such services, but also in facing demands from lesbian couples that they should be accorded access to such assisted conception services. Moreover, the storage and destruction of embryos has been a contested ethical issue. Stem cell technology has also brought about policy conflict with strongly held differences of opinion evident between legislators and an added dimension of the economic ramifications of restricting the application of such technology in a growing Australian biomedical industry. As we see in Chapter 11, even ‘smart card’ technology with the potential to revolutionise the storage of, and access to, personal health data, has produced major problems since the card is opposed by some civil libertarians as destructive of privacy and Orwellian in its capacity for the surveillance of individuals. Even the ability of medical science to prolong the life of comatose patients has caused formidable ethical problems for the state, as outlined in the discussion of end-of-life dilemmas in Chapter 13.

Nor should we neglect the significance of ideas in the identification and elaboration of policy problems. Kingdon observes that ‘ideas may sweep policy communities like fads, or may be built gradually through a process of constant discussion, speeches, hearings and bill introductions’ (Kingdon 1984 p 18). Certainly, the call for evidence-based health policy fits Kingdon’s observation, as do such ideas as harm minimisation, health as a human right, and many of the policy devices associated with neo-liberalism (or economic rationalism as it is commonly called in Australia) discussed in the following chapter.

INTERROGATING THE PROBLEM: SOME ANALYTICAL QUESTIONS

This book is intended both as a collection of studies of topics in Australian health policy and as a contribution to a problem-oriented analysis of health policy. We therefore conclude this introductory chapter by suggesting questions which the policy analyst might consider when approaching problems. These questions draw upon our brief summary of some of the literature on problem definition presented above, supplemented by our own insights.

How is the problem categorised and would a different category change how we approach it?

As Table 1.2 suggests, it is important to decide the categories in which a problem is to be considered. The approach to many problems can be altered simply by altering how we present a problem. For example, illicit drug users might be portrayed as antisocial criminals, engaging in thefts and robberies and fuelling an international industry of drug dealing. Such a problem calls for a ‘war on drugs’. Conversely, such people might be seen as victims of social and cultural forces which render them as victims, many of whom will die premature and lonely deaths unless this is prevented by a humane policy of harm minimisation and support.

Who is seeking to place the problem on the policy-making agenda?

An essential element of policy analysis is the identification of the policy players. It is therefore important to establish who is seeking to place the problem on the policy agenda. Sometimes an individual or small group of people will be instrumental in raising awareness about a problem and will demand that government does something about it, commonly through the mass media. More often this role is played by interest groups and political parties (see Ch 2). Other sources of problem identification and demands for policy response include the mass media, policy ‘think tanks’ and academic research institutions.

It might be useful to see communication about a problem as mediated by other agencies. Often it is the mass media that brings a problem to the attention of the wider public and creates an expectation that governments will do something about it. Policy makers are themselves consumers of mass media reporting. Government departments are subscribers to media monitoring services. It is difficult for a government to ignore a media campaign portraying distressing events such as the deaths of babies in hospitals or the victims of food poisoning. Interest groups serve the function of aggregating and articulating demands to respond to policy problems. Parliamentary enquiries and committees might also perform such functions by focusing on a particular problem, seeking submissions from individuals and groups and making recommendations to decision makers. Chapter 10 describes some of the diverse forces leading to a government’s decision to register traditional Chinese medical practitioners and to consider registering other complementary therapeutic modalities.

What story or discourse about the policy is being presented?

It is important to consider the language and discourse being used in problem description. The ways in which the nature of a problem, and its gravity, are communicated are significant for analysis. For some analysts, varying death rates between groups in the population will be ‘differences’, for others these will be ‘inequalities’. Such terms imply different responses. Different analysts will make different claims about the importance of a particular problem. As the chief executive officer of the Association for Prevention and Harm Reduction Programs Australia has explained, ‘Depending on whom you talk to, amphetamine usage is a full-blown crisis in Australia, a disaster just waiting to explode, or no bigger a problem than the use of any other illicit drug’ (Ryan 2007 p 19). When obesity is spoken of as an ‘epidemic’, the ground has been set both for the acceptance of the claim and an appropriate policy response.

Is the problem contested and what is the nature of the contestation?

It is rare that the nature and degree of a problem is unanimously agreed upon. A worthwhile analytical approach is to see what the grounds of contestation are and who is associated with conflict about the policy (Ch 2, see also Gardner 1995). For example, the conflict might be about technical matters, financial sustainability, economic efficiency or ethical values. It might also be about the adequacy and reliability of data to inform policy deliberations.

What is the evidence for the existence and nature of the problem?

Evidence will commonly be in the form of indicators derived from routinely collected data, although data specifically related to a particular condition are also significant.

In Chapter 4, the importance of data is discussed, particularly as they are applied to the problem of evidence-based health policy, increased costs, and the designation of priority areas in health. Care too must be taken with anecdotal evidence, which might serve to alert the analyst to a problem but must be followed by more rigorous investigation.

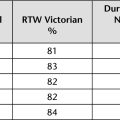

A common problem is a lack of evidence, or inappropriate evidence for policy development. The authors of Chapter 20 identify the paucity of research on injured workers returning to employment, and limitations in the methods of the studies done, as a significant problem for rehabilitation policy in Victoria.

Is causality for the problem suggested and what are the complexities of the problem?

Causality can be a minefield for the analyst. Consider obesity. It is important to recognise the complexity of the phenomenon and its multi-causal attributes. These might include such diverse factors as sedentary lifestyles, urban planning which ignores access to recreational spaces for exercise, fear of allowing children to walk to and from school or play outdoors due to perceptions of crime, the marketing activities of food corporations, and a lack of dietary eduction. Aged care policy is another area where complex factors need to be recognised. In Chapter 16 we are warned against simply equating the ageing of the population with massive healthcare burdens.

How long has the problem been recognised and what previous steps have been taken to deal with it? What knowledge and experience about the problem exists?

It is useful to identify the location of the problem in the policy process. Does it have a substantial history or is it newly emerging? In other words, is it a perennial policy problem, such as Indigenous ill health (see Ch 22) or is it an emerging one (Section 4) such as the emergence of a new disease. Sometimes policy evaluation reveals continuing or new problems, some of which are unexpectedly generated by the original policy. It is important for the analyst to be aware of the historical context of a particular problem, what previous work has been done to understand it and the nature and degree of effectiveness of previous attempts to find solutions to the problem. Shortcomings in data collection about particular problems must also be recognised.

Many policy problems are of a longstanding nature and there will usually be a history of attempts to find solutions. Gibson regards ‘health’ as a ‘wicked’ policy problem. Such problems cannot be resolved with any finality, might be defined in diverse ways, and relate to wider problems (Gibson 2003 p 304).

Is there a potential benefit from comparative analysis of a problem?

Many health policy problems are not unique to Australia or to a particular state or territory within Australia and there are valuable lessons to be learnt by exploring how other jurisdictions have responded to them. Many of the chapters in this book contain comparative perspectives, allowing the analyst to see what happened in other countries and to profit from their successes and failures (see Chs 3, 12 & 16).

Have efforts to deal with the problem caused, or are likely to cause, further or different problems?

There is always the risk that policy reforms will engender further problems, sometimes unforeseen, and sometimes due to poor policy formulation in the first place. Policy evaluation can help to identify such problems. But policy planners should also seek to anticipate what might occur. Contemporary health workforce planners must be puzzled by policies of just a few years ago which sought to restrict the number of medical doctors migrating to Australia with the intention of keeping the cost of Medicare under control. Such policies featured negative points awarded to doctors who wished to settle in Australia. Today the Australian government is actively recruiting doctors from overseas, and assisting them with cultural and health systems training (see Chs 9 & 15). In Chapter 17 serious reservations are expressed about the longer term effects of major policy reforms to the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS). It is not clear that cost-saving measures will actually succeed. Chapter 18 shows how efforts to improve help for people with mental health problems and reduce the stigma associated with mental illness resulted in many people lacking access to timely and effective care.

What are some possible solutions and how are choices limited?

Possible solutions will be limited by technical, economic, legal, systemic, value-based and political considerations, as well as the constraints of time. Health Impact Assessment has been posited as a solution to poor population health outcomes but Mahoney (Ch 5) argues that its application has been made extraordinarily difficult by just these factors. It is important for the analyst to identify such limitations in order to discount impractical suggestions and allow for the generation of realistic solutions. Chapter 3 details some serious institutional problems with consequences for the effective development and implementation of health policy. In the Australian context, policies on the provision of medical care have historically been limited by factors including the Federal Constitution’s protection of the medical and dental professions from ‘civil conscription’, the power and influence enjoyed by bodies representing the medical profession (Ch 4) and political sensitivities. Choices might be limited too, or modified, by changing conceptions and practices within the public sector. These might relate to notions of accountability, to what is in the public interest, and by whom and to whom should health programs be delivered (Ch 7).

What values are relevant to the problem and to possible solutions?

Values might affect both the definition of a problem and the solutions possible to respond to it, as well as our ability to negotiate policy. As is explained in Chapter 12, trust is an essential element of public policy. The public must trust the government and those participating in policy networks will be hampered by the absence, or by low levels, of trust. In Chapter 13 the role of the state in safeguarding human life, while recognising ethical limitations to permit dignity in dying, is explored. The authors of Chapter 14 write of efforts to assert the human rights dimensions of health and counter racism and negative cultural prejudices. Chapter 21 explores problems with the oft-asserted value of uniformity and the ramifications of efforts to realise it in the area of food safety.

In considering values, it is important for policy analysts to consider their own positions and how this might influence the conduct of their analysis in terms of objectivity and bias. In some cases, analysts prefer to state their own value position at the outset. Others might adopt a method of consciously stating different value positions.

The reader is now invited to explore the chapters in this book, making use of the concepts and insights presented in this introduction with the aim of using problems as a focus of analysis. Additional conceptual material on policy as a process can be found in Chapter 2.