Chapter 16 Mastoidectomy—Intact Canal Wall Procedure

Videos corresponding to this chapter are available online at www.expertconsult.com.

Videos corresponding to this chapter are available online at www.expertconsult.com.

Mastoidectomy can be performed in two ways in cases of cholesteatoma. The canal wall down technique is discussed in Chapter 17. This chapter addresses the canal wall up, or intact canal wall, technique. When the senior author would teach residents and fellows, he would emphasize that the call wall is intact, rather than “up.” The canal wall can be taken down surgically or left intact. The intact canal wall procedure is commonly referred to as canal wall up; however, in this chapter, the nomenclature is intact canal wall. In addition to the technique for intact canal wall, this chapter discusses the evolution of the technique, controversies in regard to intact canal wall versus canal wall down techniques, indications for canal wall down procedures, facial nerve in surgery for chronic ear disease, and management of the labyrinthine fistula.

DEFINITIONS

The common mastoid operations performed for chronic ear infections are defined in this section. Technical surgical variations peculiar to each surgeon do not alter the fundamental classification. The basic classifications have remained unchanged since 1974.1

EVOLUTION OF TECHNIQUE

When tympanoplasty was first introduced by Wullstein2 and Zollner,3 exenteration of the mastoid was the rule. Two problems eventually became apparent. Moisture in the cavity had a deleterious effect on the full-thickness skin used to graft the tympanic membrane, and the narrowed middle ear space created in the classic types III and IV tympanoplasty was prone to collapse, nullifying any hearing improvement (see Chapter 13).

It became apparent that if satisfactory hearing results were to be obtained, some method of avoiding a narrow middle ear space would be necessary. Many investigators thought that the best way of solving this problem was by not creating an exteriorized cavity, but by reconstructing the tympanic membrane in a normal position, and then inserting some type of tissue or prosthetic device to re-establish the sound pressure transfer mechanism (see Chapter 13). Although this concept led to better hearing results, many problems developed over the years, some of which are still seen.

The physicians at the House Ear Clinic began performing intact canal wall tympanoplasty with mastoidectomy in 1958, under the direction of William House.4 By 1961, more than half of all cholesteatoma cases were managed at the House Ear Clinic with an intact canal wall technique. Many revision operations were required for correction of recurrence of cholesteatoma resulting from retraction pockets. As a result, many physicians at the House Ear Clinic reverted to taking the canal wall down and then obliterating the cavity with muscle, based on a procedure suggested by Rambo.5 In 1963, 50% of cholesteatoma cases were managed this way.

By 1964, it was realized that the technique of obliteration did not eliminate the cavity and the problems involved. In addition, the routine use of plastic sheeting through the facial recess in the intact canal wall procedure was reducing the number of cases that had to be revised because of retraction pockets (recurrent cholesteatoma). From that point on, the percentage of cases managed by a canal wall down technique gradually decreased to 10% in 1970. Since then, although there have been fluctuations, on average 15% to 30% of chronic ear surgery is managed by canal wall down procedures.6

CONTROVERSY

The controversy over intact canal wall versus canal wall down centers mostly on safety—safety of the operative procedure and safety over the ensuing years.7 The technical ability of the surgeon also should be taken into consideration. In the surgery of aural cholesteatoma, be it intact canal wall or canal wall down, judgment and technical ability are major factors in the outcome.8 Let us assume that the technical ability and judgment are superior in the two groups. Why is there a difference in opinion as to what is best for the patient?

Are hearing results a factor? Experienced otologic surgeons do not find much difference in hearing results. Surgeons are very careful not to narrow the middle ear space (see Chapter 13) and stage the operation almost as frequently as in an intact canal wall operation (see Chapter 18).

Is there a difference in the healing? Intact canal wall procedures, with lateral surface grafting (see Chapter 9), may take 6 to 8 weeks to heal. Open cavities frequently require 3 to 4 months and occasionally 6 to 8 months, and there is a small percentage that are never free of minor moisture problems.

What about residual and recurrent disease? Some surgeons would argue that a primary canal wall down approach results in one operation, not two. Most experienced surgeons who use intact canal wall and canal wall down procedures find little difference in the incidence of middle ear residual disease, or disease left behind. They also find little difference in the incidence of staging the operation (see Chapter 18).

Recurrent cholesteatoma is a different matter. Recurrent cholesteatoma characteristically results from a posterosuperior retraction pocket,9,10 which occurs only in intact canal wall procedures. Surgeons who have reported a 20% to 40% incidence of recurrent cholesteatoma have failed, with rare exceptions, to stage the operation when indicated (75% of the time), and have failed to use plastic sheeting through the facial recess, even when the operation was being performed in one stage. Advocates of the intact canal wall procedure (surgeons who have had extensive experience) have less than a 5% incidence of recurrent cholesteatoma.

INDICATIONS FOR MASTOIDECTOMY

Mastoidectomy may be indicated in tympanoplasty surgery to eliminate disease, to explore the mastoid to ensure that there is no disease, to enlarge the air-containing middle ear–antral space, or occasionally to create temporary postauricular drainage (with a catheter) in patients with compromised eustachian tube problems or uncontrolled mucosal infection.11 The most common indication is the treatment of cholesteatoma and the associated infection.

INDICATIONS FOR EXTERIORIZED MASTOID CAVITY

The House Ear Clinic physicians prefer not to create a cavity, but they may do so sometimes. That decision may be made preoperatively, but more often than not, the operation is begun as an intact canal wall procedure, and the decision to exteriorize the mastoid is made intraoperatively.12

Preoperative Decisions

In labyrinthine fistula cases, one may decide before the operation to use a canal wall down operation if the mastoid is small, or if the opposite ear has a cholesteatoma that would require surgery. If the hearing is serviceable, one would probably perform a classic modified radical procedure, particularly in patients in poor health or in elderly patients.12–14

PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION AND TREATMENT

The diagnosis of cholesteatoma is based on a well-taken history by the physician and a careful examination of the ear under an operating microscope to confirm ingrowth of skin into the middle ear, the epitympanum, or both. The only routine testing is the hearing test. This test is not related to making the diagnosis, but is done to allow proper counseling. Occasionally, the hearing test results in a change of approach to the surgery, as noted in the preceding section. Radiographs and imaging studies play little part in making the diagnosis or directing the surgical approach. These tests are usually obtained if there is a complication, or if one is considered likely (e.g., semicircular canal fistula, facial paralysis, meningitis, or other intracranial complications).14 Under these circumstances, imaging studies rarely make a difference in the overall surgical approach, but should allow the surgeon to predict any complications or sequelae. The patient and family can be counseled properly and forewarned of problems.

Treatment of a Chronically Draining Ear

In an ear without cholesteatoma (the benign central perforation), local treatment is indicated to obtain a dry ear before surgery (see Chapter 8). It is preferable to have the ear dry for 3 or 4 weeks before tympanic membrane grafting. If the ear is draining at the time of surgery, it is probably best to perform at least an antrostomy through the mastoid cortex to ensure drainage while the tympanic membrane graft is healing.11 It is more likely that a mucosal problem could dictate staging the operation if the ear is still draining at the time of surgery (see Chapter 18).

PREOPERATIVE COUNSELING

In the back of the Chronic Ear Patient Discussion Booklet, there is a section called Risks and Complications of Surgery. The only serious complication that occurs with any regularity is a total, 100% loss of hearing in the ear operated on. The likelihood of this happening is 1% to 2%; all of the other things listed in the booklet are either very remote or are temporary. (See Appendix 1 in Chapter 9 for the complete Risk and Complications sheet.)

PREOPERATIVE PREPARATION OF THE PATIENT

Preoperative preparation of the patient differs little from what was described for tympanic membrane grafting (see Chapter 9). The operation is done under general anesthesia, unless the patient requests otherwise. Preoperative antibiotics are not routinely used.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

Just as the preparation before and in surgery is the same as that described for tympanic membrane grafting (see Chapter 9), the initial steps are also the same: making canal incisions, elevating the vascular strip, turning the ear forward, removing and dehydrating the temporalis fascia, removing canal skin, enlarging the ear canal by removing the overhanging bone anteriorly and inferiorly, and ensuring that the remnant is de-epithelialized.15

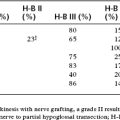

Mastoid Exenteration

The mastoid is exenterated, under the microscope, using a drill with various-sized round cutting burrs. Continuous suction-irrigation during drilling is used to cool the bone, to keep the field clean at all times, and to prevent clogging of the burr by bone dust. The initial burr cut is made along the linea temporalis. This marks the lowest point of the middle fossa dura in most cases. The second burr cut is along a line perpendicular to the one just described and tangent to the posterior margin of the ear canal (Fig. 16-1). These two burr cuts outline a triangular area posterior to the ear canal cut, the apex of which is at the spine of Henle. Projected into the mastoid, parallel to the direction of the ear canal, the apex of this triangle is directly over the lateral semicircular canal. The only structure of importance lying within this triangle as one proceeds with the exenteration is the lateral (sigmoid) sinus.

FIGURE 16-1 Burr cuts to begin mastoidectomy. Note lateral semicircular canal ghosted in.

After the lateral semicircular canal has been identified and the cortical mastoidectomy has been completed, the zygomatic root is exenterated to allow access to epitympanum. The posterior bony canal wall is thinned at this time (Fig. 16-2).

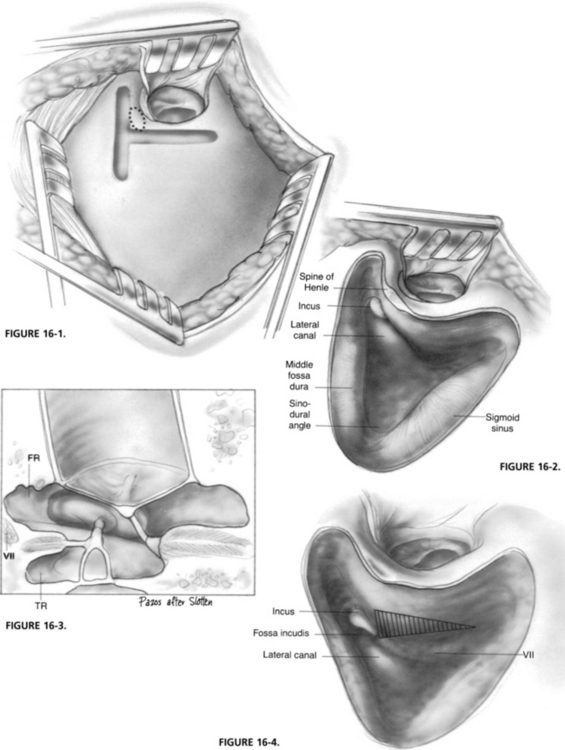

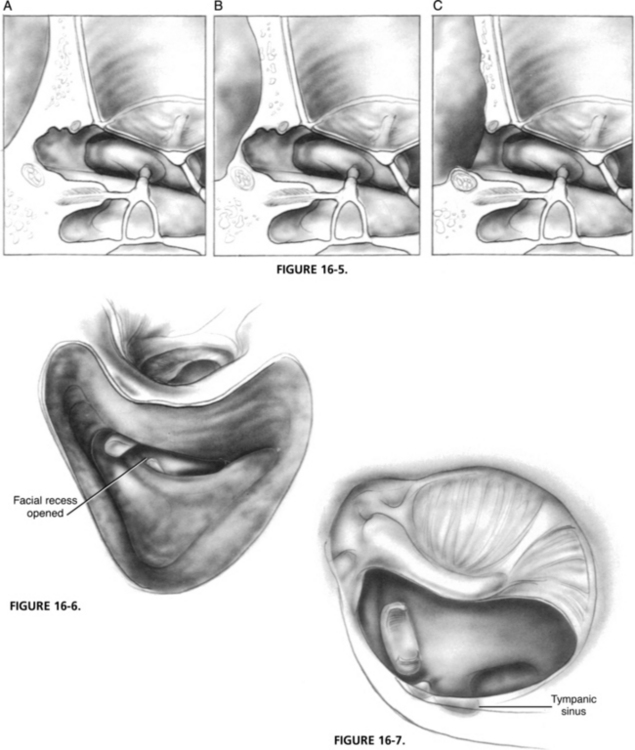

Opening the Facial Recess

The facial recess is one of the posterior recesses of the middle ear. It is bordered laterally by the chorda tympani, medially by the upper mastoid segment of the facial nerve, and superiorly by bone of the fossa incudis (Fig. 16-3). This recess is frequently the seat of a cholesteatoma, particularly when the cholesteatoma is associated with a perforation below the posterior malleal fold. Bone in this area may be cellular even in poorly developed mastoid.

The landmark for opening into the facial recess is the fossa incudis. One visualizes the triangular area that is inferior to the fossa and is bordered by bone of the fossa incudis superiorly, the upper mastoid segment of the facial nerve medially, and the chorda tympani laterally (Fig. 16-4). The bone is saucerized in this area with a large cutting burr. When the bony canal wall lateral to the recess has been thinned satisfactorily (care being taken not to perforate into the external canal), bone removal is continued with a smaller cutting burr. One should always stroke the burr parallel to the direction of the facial nerve, never allowing the burr to pass the bone of the fossa incudis superiorly (Fig. 16-5).

FIGURE 16-5 A-C, Horizontal cross section showing progressive saucerization and opening into the facial recess; compare with Figure 11-13.

The facial recess is opened from the mastoid to remove disease in the area, to gain additional access to the posterior middle ear (oval and round windows), to gain a better view of the tympanic segment of the facial nerve, and to facilitate postoperative aeration of the mastoid. Opening into the middle ear through the facial recess is a key step in performing an intact canal wall tympanoplasty with mastoidectomy; with rare exceptions, it should not be omitted (Fig. 16-6).

It is unnecessary to expose the nerve with this approach, but there is no harm in doing so. The facial nerve is quite resistant to gentle trauma.16 One can use the cutting burrs when approaching the nerve in the region of the facial recess. Bone removal is quicker than with the diamond stone, and it is easier to determine when the nerve is exposed. To make this differentiation, the exposed area can be probed with a Rosen needle. If the exposed area is nerve sheath, it rebounds immediately after release of the probe; it “bounces back.” If what has been uncovered is mucosa or cholesteatoma, one may note that it will “come back to you,” but that it does not bounce back or rebound. After the recess has been opened, the incus, if present, is removed along with bone of the fossa incudis if involved with cholesteatoma. It is then possible to see the pyramidal eminence, the oval and round windows, and the part of the tympanic portion of the facial nerve lying posterior to the cochleariform process.

Elimination of Disease

The areas that are most difficult to see with this or any other approach, even radical mastoidectomy, are the posterior middle ear recess: infrapyramidal and tympanic.17 These are the areas posterior to and between the oval and round windows (Fig. 16-7). They extend for a variable distance medial to the pyramidal process and facial nerve (and lateral to the posterior semicircular canal). They are often the seat of cholesteatoma, particularly in cases associated with perforations below the posterior malleal ligament. The area must be cleaned with a right angle dissector. Removal of the pyramidal process and adjacent bone with a diamond burr may be necessary sometimes to facilitate the cleaning, but can be done safely only in a case where the stapes superstructure and tendon are missing. If the tympanic recess is deep, and there is disease in it, it can be approached in a well-developed mastoid from the mastoid side, medial to the facial nerve and lateral to the posterior semicircular canal.19 This approach is not usually feasible, or necessary, but should be kept in mind. It is an approach commonly used in connection with glomus tumor surgery. Infrequently, otologic endoscopes for viewing the posterior recesses from the opposite side of the usual surgical position of the operative ear may be helpful (viewing from the patient’s right side for a left ear or from the left side for the right ear).

Use of Plastic Sheeting

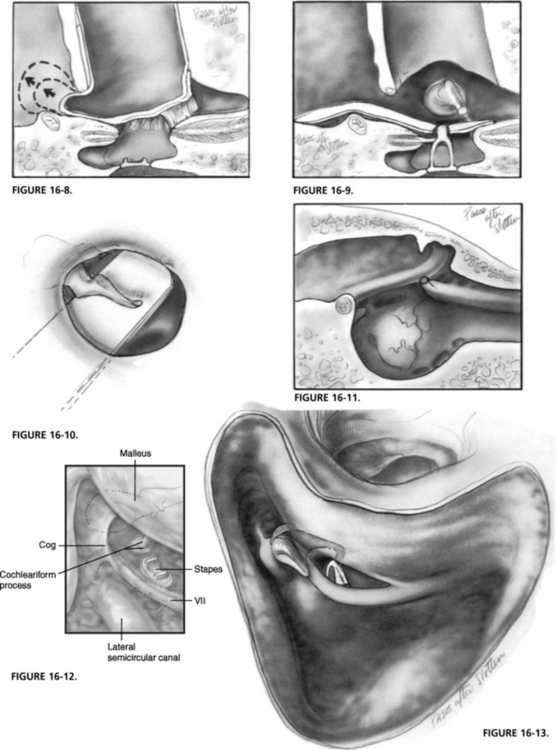

Plastic sheeting is used routinely in the intact canal wall procedure, regardless of the status of the middle ear mucosa, to prevent adhesions between the raw undersurface of the tympanic membrane graft and the denuded bone of the epitympanum and facial recess area. (Other uses of plastic sheeting are discussed in Chapter 18.) Before it was realized that plastic sheeting should be used through the facial recess, there were many cases of recurrence of cholesteatoma because of retraction of the tympanic membrane into the facial recess and epitympanum (Fig. 16-8). If the operation is not being staged, thin silicone sheeting is used through the recess. An opening can be created in the plastic to allow for reconstruction to the stapes capitulum (Fig. 16-9). When staging of the operation is indicated, as it usually is in cholesteatoma cases, thick silicone sheeting is used (Fig. 16-10) (see Chapter 18).

FIGURE 16-11. Parasagittal section through the middle ear of the right temporal bone to show landmarks. Facial nerve lies superior to the oval window and posterior (also superior) to the cochleariform process. The nerve lies superior, and also posterior, to the pyramidal process, and anterior to the cog in the floor of the supratubal recess. The cog is a ridge of bone extending inferiorly from the tegmen epitympani, above the cochleariform process (see Fig. 16-12). Note the relationship of the semicanal for the tensor tympani and a groove in the promontory for the tympanic nerve of Jacobson.

FIGURE 16-12. View from the mastoid into the epitympanum (facial recess has been opened). Malleus head has been ghosted in to show the relationship to the cog (compare with Fig. 16-11). The cog is a ridge of bone extending inferiorly from the tegmen epitympani, anterior to the malleus head, above the cochleariform process.

Completion of the Operation

The tympanic membrane is reconstructed with rehydrated fascia, the ear canal skin is replaced on the denuded bone, packing is inserted, the vascular strip is replaced, and closure postauricularly is with subcutaneous suture, all as described for tympanic membrane grafting (see Chapter 9). The mastoid is routinely irrigated with antibiotic solution, removing all bone dust and debris, and decreasing the likelihood of postoperative inflammation or infection. A superficial Penrose drain is occasionally indicated when oozing has been a problem. The drain extends from the area of the fascia removal and exits at the lower part of the incision. This drain is usually attached to the dressing so that it is removed on the first postoperative day.

Dressing and Postoperative Care

There is no difference between the dressing or postoperative care for this procedure and the procedure for tympanic membrane grafting (see Chapter 9). The schedule and plan for office visits are the same. This is now most commonly performed as an outpatient procedure. The authors frequently use a Glasscock pressure dressing for up to 1 week after the surgery to prevent patient telephone calls regarding the “outstanding ear.”

FACIAL NERVE IN SURGERY OF CHRONIC OTITIS MEDIA

One of the greatest fears of the inexperienced surgeon is that damage to the facial nerve may occur during a mastoidectomy.16 In the words of the senior author: “The facial nerve is exactly where it is supposed to be.” Fear may result in avoidance of the nerve rather than positive identification; this can result in inadvertent damage to the nerve that has not been identified. In canal wall down surgery, this fear results in the inadequacy of some of the surgical procedures, leaving the posterior bony canal wall (the facial ridge) high, creating a bean-shaped cavity. Familiarity with the facial nerve results in respect: respect for helping to guide one throughout the temporal bone and respect for its ability to withstand manipulations and minor trauma. There are three segments to the facial nerve: labyrinthine, tympanic, and mastoid. In surgery of chronic otitis media, concern is with the tympanic and mastoid segments.

Tympanic Segment

The upper edge of the oval window is bordered by the facial nerve (Fig. 16-11). If this is not apparent, the cochleariform process may be identified. The facial nerve lies posterior and superior to the cochleariform. One may also identify the pyramidal process, and note that the facial nerve lies above and behind this structure. When none of these landmarks are apparent, the semicanal for the tensor tympani may be identified in the anterior middle ear and followed posteriorly. Its inferior border is continuous with the upper margin of the oval window, the facial nerve.

The cog is a ridge of bone that extends inferiorly from the tegmen epitympani and partially separates the anterior tympanic compartment (supratubal recess) from the mesoepitympanum. The cog lies immediately superior to, and just slightly posterior to, the cochleariform process and anterior to the head of the malleus (Fig. 16-12). As the facial nerve runs between the cochleariform process and the geniculate ganglion, it courses under the base of the cog and anterior to it in the floor of the supratubal recess.

Mastoid Segment

In mastoidectomy, the initial landmarks within the temporal bone are the mastoid antrum and the lateral semicircular canal. When the lateral canal is identified, the surgeon knows where the facial nerve is and is prepared to remove all the diseased tissue from the mastoid (Fig. 16-13). An intimate knowledge of this three-dimensional anatomy and the relationship of surrounding structures to the facial nerve is the major reason a trainee in otology must spend sufficient time dissecting the temporal bone in the laboratory before operating on patients.

The short crus of the incus is located inferior, and slightly lateral, to the anterior portion of the lateral canal bulge. The fossa incudis is at the tip of the short crus. The facial nerve lies medial to the fossa incudis and inferior to the lateral canal. As the nerve travels inferiorly in its course to the stylomastoid foramen, it travels in a slightly posterior direction, in most instances, and travels laterally. (The reader would be well served by reading the article by Litton and associates on the relationship of the fallopian canal to the tympanic annulus.18) The senior author routinely referred otology/neurotology fellows to this classic reference and supplied them for copies for review on multiple occasions.

MANAGEMENT OF THE LABYRINTHINE FISTULA

There is no way of knowing for certain preoperatively that a patient with a cholesteatoma does not have a labyrinthine fistula; 10% of such patients do.13 Each mastoid must be approached as if a fistula existed. When the cholesteatomal sac is encountered in the mastoid, it should be opened, and the medial wall of the sac lying on the lateral semicircular canal should be palpated to detect any bony dehiscence. Bony erosion may be obvious by flattening of the usual prominence of the lateral canal.

If there appears to be a fistula, a decision has to be made regarding management of the mastoid: continue as an intact canal wall procedure, or create an open cavity? If an open cavity is to be created, the matrix may be left on the fistula permanently.12

If the operation is to continue as an intact canal wall procedure, the matrix around the fistula is carefully incised. The rest of the matrix may be removed without removing the segment covering the fistula. If a decision has been made that the operation is to be performed in two stages (see Chapter 18), the matrix is left over the fistula, to be removed at the planned second stage when the ear is healed. If the operation is to be performed in one stage, the operation is completed, including grafting, ossicular chain reconstruction, and packing of the ear canal. If one suspects that the fistula is small, it is reasonable to remove the matrix at this time and cover the fistula immediately with fascia. If the fistula appears to be large, or the ear is infected, it is probably best to leave the matrix and come back into the mastoid in 6 months to remove it.

REPAIR OF CANAL WALL DEFECTS

Defects Resulting from Disease

In most cases, canal wall destruction is limited to the lateral epitympanic wall (Fig. 16-14). If a second-stage procedure is planned (see Chapter 18), it is wise not to reconstruct the defect; the thick silicone sheeting would prevent a retraction pocket between stages 1 and 2. At stage 2, after removing the plastic, one may see through the defect to detect any residual disease. The defect may be repaired at that time with ear cartilage. Smaller defects can be repaired with bone pâté. If a second-stage operation is not indicated, the defect may be repaired in a similar way after the graft has been tucked under the bony defect (Fig. 16-15).

1. Committee on Conservation of Hearing of the American Academy of Ophthalmology and Otolaryngology. Standard classification for surgery of chronic ear infection. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1965;81:204-205.

2. Wullstein H. Theory and practice of tympanoplasty. Laryngoscope. 1956;66:1076-1093.

3. Zollner F. Principles of plastic surgery of the sound-conducting apparatus. J Laryngol Otol. 1955;69:637-652.

4. Sheehy J.L., Patterson M.E. Intact canal wall tympanoplasty with mastoidectomy. Laryngoscope. 1967;77:1502-1542.

5. Rambo J.H.T. Further experience with musculoplasty. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1960;71:428-436.

6. Syms M.J., Lexford W.M. Management of cholesteatoma: Status of a canal wall. Laryngoscopy. 2003;113:443-448.

7. Sheehy J.L. Intact canal wall tympanoplasty with mastoidectomy. In: Snow J.B., editor. Controversies in Otolaryngology. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1980.

8. Sheehy J.L., Brackmann D.E.. Surgery of Chronic Ear Disease: What We Do and Why We Do It. Instructional Courses. vol. 6, 1993. Mosby, St Louis.

9. Sheehy J.L. Cholesteatoma surgery: Residual and recurrent disease. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1977;86:451-462.

10. Sheehy J.L., Robinson J.V. Cholesteatoma surgery at the Otologic Medical Group: Residual and recurrent disease: A report on 307 revision operations. Am J Otol. 1982;3:209-215.

11. Sheehy J.L.. Chronic tympanomastoiditis. Gates G.A., editor. Current Therapy in Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. vol. 4, 1990. Decker, Philadelphia, 19-22.

12. Sheehy J.L. Cholesteatoma surgery: Canal wall down procedures. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1988;97:30-35.

13. Sheehy J.L., Brackmann D.E. Cholesteatoma surgery: Management of the labyrinthine fistula. Laryngoscope. 1979;89:78-87.

14. Sheehy J.L., Brackmann D.E., Graham M.D. Complications of cholesteatoma: A report on 1024 cases. In: McCabe B., Sade J., Abramson M., editors. Cholesteatoma, First International Conference. Birmingham, AL: Aesculapius, 1977.

15. Sheehy J.L., Brackmann D.E. Surgery of chronic otitis media. In: English G.M., editor. Otolaryngology. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1994.

16. Sheehy J.L. Facial nerve in surgery of chronic otitis media. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1974;7:493-503.

17. Donaldson J.A., Anson B.J., Warpeha R.L., et al. The surgical anatomy of the sinus tympani. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1970;91:219-227.

18. Litton W.B., Krause C.J., Anson B.A., et al. The relationship of the facial canal to the annular sulcus. Laryngoscope. 1969;79:1584-1604.

19. Pickett BW, Cail WS, Lambert PR: Sinus tympani: Anatomic considerations, computer tomography, and a discussion of the retrofacial approach for removal of disease.